Poets Keep Talking

Poets writing, reading, sharing, living in the museum

Poets in the Museum is a project that welcomes a group of local poets within the hallways of the MAMbo – Modern Art Museum of Bologna to read, write and share their work. Conceived by writer and translator Allison Grimaldi Donahue in collaboration with assistant curator Caterina Molteni, Poets in the Museum stems from the desire to bring the practices of the poet and the one of the artist closer, by exploring new ways of art writing through the poet’s engagement, beside critics and curators’.

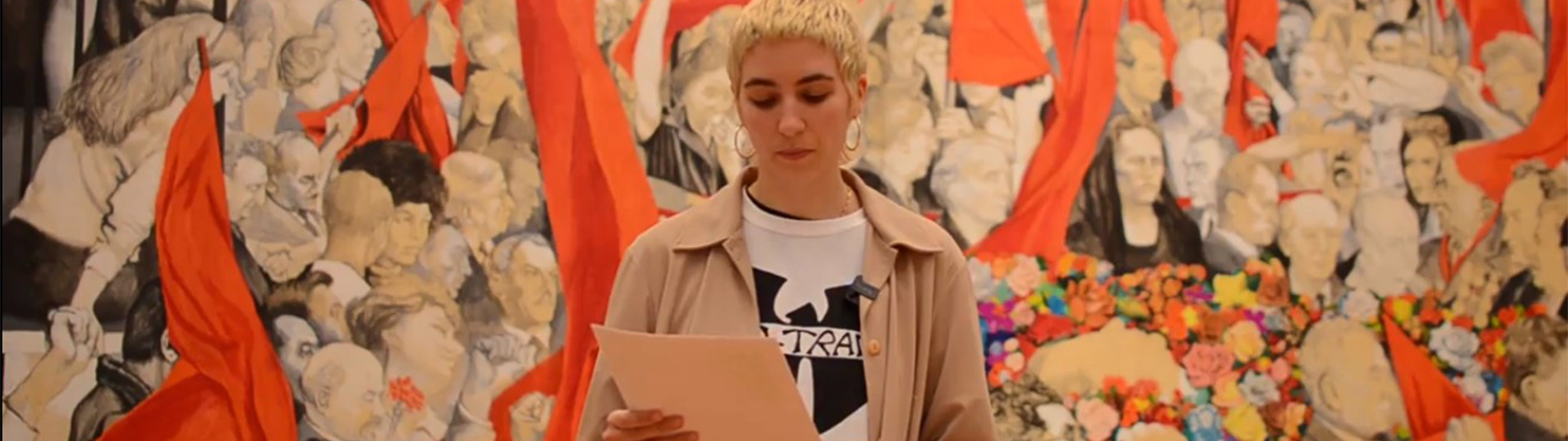

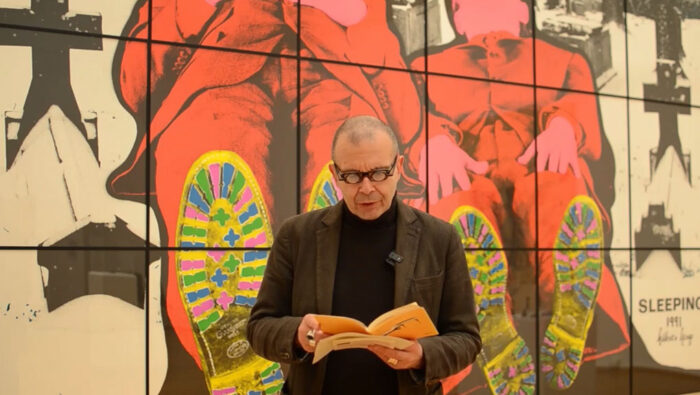

A group of poets move freely through the halls of the museum. In their hands they hold books and paper, they talk amongst themselves, they point at certain works, they notice new particularities. Someone began to read, behind me, speaking of Bachelard’s vertical time, discovering a commonality with Eva Marisaldi’s practice. A little later, I hear a voice cry: “To Gina, Gina, Gina”: we are in the area dedicated to the “Settimana della Performance,” there is talk of fires, of wounds, but there’s a feeling of softness, too. I give a hint of a smile. The people around me gather, they stop and listen. They’re a bit surprised, a bit intimidated, but I have the feeling they’re enjoying it.

I keep thinking of how lucky I’ve been, to walk around the museum even during the covid restrictions, that such a beautiful place might be called my place of work. Finally, the state finds itself implying that the work of the artist is work, even in a small way, by letting us into a space. By artists I mean visual artists, but I also mean myself, a poet. Maybe even more so than other kinds of artists, the poet lives in fear of the Institution. Or maybe it’s fear quickly followed up by neglect. At least in 2021. Whether we’re talking about poets here in Italy or poets in America, where there are endowed chairs in creative writing, though very few of them, of course. In either case, this feels true. I mention both because those are my realities, and each reality provides very little for the poet and so we learn to do without, and we learn to subvert the realities offered. Il nuovo forno del pane opens up the museum as a place of work to artists, which is actually not very common at all. The museum itself is not typically where the works are made but where they spend a kind of afterlife, or a better word might be eternity. Living in the museum as a poet is a continual conversation, and ongoing discussion. It’s the sort of relationship where the poet keeps talking and whether there is a response or not, they keep talking. I come here every day; I come to my studio space and write and read and talk to others but mostly I listen and write things down.

The idea of putting written poetry on stage arrived with our enthusiasm for the reopening. After months in which the only inhabitants of the museum were us— the employees and the artists in residence at Il Nuovo Forno del Pane— it seemed important to bring in some voices to surround the works. For us, the museum had never really been closed, we saw each other every day for a cigarette break, a coffee, an announcement to share, a new project to discuss. We took to the habit of inhabiting the museum: we had the privilege of going to the library, of turning on the lights in a gallery to look at a work in person, of having lunch where, until the previous month, there had been paintings hanging. There was also much talk of poetry, it was always touched upon lightly, becoming a constant presence. From Bekhbaatar’s portfolio with some handwritten verses, to Mattia’s and Paolo’s passion for Patrizia Cavalli, to Ruth’s audio tracks, to Letizia’s embroidery, Vincenzo’s way of talking about still lifes, to the poetry of Leonard Sàntè, and in Giuseppe’s short stories in blue and red pencil. When Allison decided to bring a group of poets to write in the permanent collection of the museum, we still didn’t know how it would go, or what form the invitation might take.

I have found over the years that works of art, of all kinds, give me a different energy than reading other poets gives me. A work of art, especially when it isn’t figurative, opens us to new ways of thinking, opens us to doubt. The best reading and writing do this for us as well, but it’s harder to swallow for a lot of folks. So, by bringing contemporary poets into the museum, by writing and reading in the museum I am saying and the curators at MAMbo are saying that this space is open to a diverse range of art, work, and labor practices. I say reading and writing because I very much believe reading and writing are one and the same, just like Lisa Robertson mentioned in her reading and talk with us, in our public program, a couple of months ago. Contact with visual art, depending on what it is, where and when it’s from, opens up different questions, and different feelings. And also allows the poet to focus on parts of writing poetry that might sometimes be taken for granted: shape, color. Visual art offers the poet new ways of organizing language and thus organizing thoughts. Or vice-versa. Yesterday I had this really lovely conversation with Marianna Vecellio from Castello di Rivoli about what poetry brings to the world of art. It was this very relaxed studio visit where she asked me to actually read her some poems during our video chat and I really liked that. Already, a poet doing a studio visit, right, already something so different and new. But we talked about how the poet in the museum is a de-professionalizing presence. And I remembered someone once saying to me “ah yes, the poets, the really poor ones. They keep us grounded.” And it’s true. And sadly (for us) it may be what keeps us legitimate. Some people might call it purity, I wouldn’t do that, because I don’t think poverty or neglect keeps anyone pure. But it is true, we don’t have any market waiting for our work, and in this way we’re freed of the pressure of making work to fit that market. Don’t take this the wrong way, I want, and I believe that poets deserve, to earn from their work. Yet, I am happy that we aren’t so easily turned into a commodity. This allows our thinking to continue its work in the unknowable, in Keat’s negative capability.

I like the idea of an invasion, of provoking an incident, of putting a regulated experience in crisis, with touching, without getting close to each other, but only invading the ears of the spectator with words and verses. Is it possible to develop strategies of contact without actually touching one another? Now more than ever it seemed to me that the word really has its own material, its physical depth, tactile, either while it is read or while it is heard or when it is written. Even if I can’t be close to you, I can read you a poem, slowly tell you one of my feelings before a work, of a new combination of words.

To poeticize, to compose verses, to write poetry, to read them, are in this sense proposed as a practice: an exercise that stimulates, that brings to life, that allows for slippage, that doesn’t transmit interpretations but walks firm-footed in a wild field. The poets in the museum propose, before all else, a method that goes beyond the specialized writing of the museum curator, going to the other side of discipline, infringing upon it in the name of the continual negotiation between common meanings and the new words they can coin. Elimination the authority of theories in favor of a sensibility that renews itself between the silent works and the sharp voices, calm and deep, from whomever decides to begin reading. If historical and thematic narration of the works exhibited in the museum remains necessary, it is important to develop strategies that make parallel paths visible, approaches that don’t provide lines of reading but offer an experience, which is as evocative as it is material and perceptible. To stage the common presence of diverse methods of the museum’s work with the public— the creation of thematic galleries, writing descriptive captions, historical reconstructions— and new behaviors which are the fruit of poetic-artistic practices, allows the Institution to put its own criteria in constant discussion, supplying the audience with a wider interpretive mirror.

At the same time, the museum becomes a theatre of relationships between the works, the poets, the public, encouraging the collision of thoughts, where chance encounters between people is always becoming more difficult. In a society in which the political field of relationships is filtered by rules for a secure coexistence, those practices that work through a paradoxical language become central, that keep one foot on the side of the rules but plot in secret—surprising—possible escape routes.

At a certain point in The Undercommons Fred Moten and Stefano Harney write about entering the undercommons of the Institution, “To enter this space is to inhabit the ruptural and enraptured disclosure of the commons that fugitive enlightenment enacts, the criminal, matricidal, queer, in the cistern, on the stroll of the stolen life, the life stolen by the enlightenment and stolen back, where the commons give refuge, where the refuge gives commons. What the beyond of teaching is really about is not finishing oneself, not passing, not completing…” Now Moten and Harney are talking about the university, but museums fit into the same category here as institutions of knowledge, of making the world knowable. Poetry returns art to its enraptured, endless, unfinished status, returns it to its presences among the unknowable things in the world. And so, for the poet or the artist to inhabit the museum is to disrupt its usual operations, to upset its production of knowledge with messier, less understandable but hopefully just as accessible actions that allow the public to enter into this space of the beyond knowing, to stay with questions. Poetry itself and the thirteen of us working in Il nuovo forno del pane are this living, breathing corrective for what Carla Lonzi calls “the vices of the Institution.” To help everyone remember that art belongs first to the people and not to institutions, that it belongs to the beyond.