Personal Explored Temptation

or “Giving Myself a Six-year Retrospective” by Angelo Plessas

In one of the main streets of Kypseli, Athens’ emerging cultural district, stands P.E.T. Projects. Launched in 2019, P.E.T. is an artist-run space that has since been offering independent shows featuring the protagonists of the city’s contemporary art scene. The venue is nestled in a maze of narrow streets constellated by orange trees, homey tavernas, and crumbling bourgeois buildings festooned by graffiti. One of the hubs contributing to Kypseli’s spring, P.E.T.’s openings always attract a committed audience engrossed by the sincere energy of its wizardly owner, Greek-Italian artist Angelo Plessas. A talent for weaving connections and knitting unconventional artworks, Plessas has made the space, which also serves as his studio, a living translation of his communal practice. This year, in celebration of an odd six-year milestone, he decided to treat himself with a retrospective showcasing a portion of his multifaceted body of work, acting at once as protagonist, curator, and writer for his exhibition.

The show is entitled Personal Explored Temptation (the only rule at P.E.T. is that every title must compose its acronym), while the subtitle reads Giving Myself a Six Years Retrospective (a homage to pioneer feminist artist Mary Beth Edelson). According to Plessas, the objective of his celebratory display is nothing less than “to initiate collective or individual rituals involving psychoanalysis, meditation, and healing.” These introspective themes crossroad at the centerpiece, a round wooden table with four colorful chairs that appear to have landed from an alien amusement park. Plessas recently designed the furniture as a part of his new domestic appliances for his countryside and city domains (he’s working on a bed, a sofa, and a throne/armchair). In the exhibition space, the table hosts the Transformation Game, a board game he discovered in 2017 at Kassel’s Documenta 14 while researching unorthodox ways of conducting psychoanalytic sessions within an installment of his international residency program, The Eternal Internet Brotherhood/Sisterhood.

The Transformation Game was authored by Joy Drake and Kathy Tyler in the late seventies at Findhorn, a Scottish radical community. Founded in the fifties, Findhorn grew from a family-run vegetable garden towards establishing the Global Ecovillage Network, an assembly of similar ventures fostering practical research into alternative ways of living. Nowadays, Findhorn cooperates with the United Nations in the frame of the UN Sustainable Development Goals, actively researching how to attain grand objectives that match Plessas’ ethics: “By 2030, ensure all learners acquire knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including among others through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship, and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development.”

Months ago, I played the Transformation Game in southern France with the artists Sofia Stevi and Eleni Bagaki and the curator Filipa Ramos. Invited by Plessas, we sat in the lush garden of Moulin des Ribes. In this villa, Società delle Api, an independent non-profit founded by collector Silvia Fiorucci, hosts annual meetings and residencies (Plessas curated the 2023 summer solstice gathering entitled The House of All Beings). The game requires four persons, and throughout the session, a facilitator interrogates each participant about her existential beliefs and her convictions regarding the other players. The closer the participants are, the better the insights they gain about themselves (one must abandon shame to provide confessions) and their interrelationship (one must confront fear to speak the truth about others). Similarly to the dedication required by a classical psychoanalytic therapy, the process should be repeated among the members of a particular group of people over the long run to achieve effectiveness. The Transformation Game merges subjective and collective healing, mimicking a process of ecological peacebuilding.

In the last months, Plessas realized that the game’s outcomes could only be appreciated through a demanding commitment. Determined to develop the ritualistic aspect of the game without renouncing the psychological mechanisms of the original, he decided to design his own version, entitled The Game of All Beings. Six players can play it, each impersonating a different entity: human, animal, plant, machine, atom, and extraterrestrial. Dicing their way towards the last square of the board, the participants draw cards and role-play as representatives of a larger group of beings rather than for themselves. In solidarity with his poetics, which encourages a constructive and adventurous metamorphosis of the self, Plessas designed a posthumanist mechanism that complicates the one-dimensional concept of subjectivity presupposed by the Transformation Game. Those open to the same challenges will soon have the chance to try out their persona, getting a copy of the game, as NERO will publish it as a conclusion of The House of All Beings.

All the artworks presented in Personal Explored Temptation relate to the mind-altering capabilities explored in the Transformation Game. Its centrality comes from Plessas’ strong belief in art’s capability of promoting personality growth for the betterment of the individual, but also in favor of the health of the entire planet and beyond. A long-standing reflection on self-transformation dynamics led Plessas to conceive specific pieces aimed at facilitating these alchemical processes. Since it is impossible to attain any personal renewal without the help of a sanctuary protecting the mutating, unformed soul, he created a series of shielding artworks such as his Malismans—neon lights shaped as mysterious safeguarding emblems. Their force expands through the mirrors standing behind them, irradiating the visitors at P.E.T. with a profusion of white magic.

In the same spirit, beneficial symbols such as mandalas, light rays, and iatric eyes adorn Plessas’ polyester fabric works. These padded pieces take inspiration from the theories of Wilhelm Reich—the psychiatrist and psychoanalyst author of the 1933 classic The Mass Psychology of Fascism, a textbook for the student protests of 1968. After a life spent trying to warn Europeans about the mortal perils of sexual repression and nationalist ideologies, the irregular doctor came up with the idea of “orgone,” a life-sustaining energy shared by all living beings. In the 1950s, Reich became alarmed about a future where humans would spend their lives immersed in malicious electromagnetic fields. He posited that polyester fabric would encumber the nefarious waves, promoting the safety of orgone and the well-being of living creatures. Following the prescription, Plessas used this material to counteract the contemporary inundation of oscillatory forces, fashioning utilitarian artworks.

Incorporating a defensive feature, Plessas’ fabrics—banners, quilts, and robes—interrogate the contemporary cult of connectedness. The artist claims that higher forms of relation between ourselves and the cosmos are possible, yet any evolutionary process entails a distancing device. He produces everything by hand—he learned sewing techniques by attending a course with local tailors, a practice he initiated to halt his screen addiction. At P.E.T., hanging pieces guard the space, creating a beneficial, analogue environment. Plessas employs many of his fabrics as wearables and bodily interfaces. His quilts are part of ceremonial performances where people can sit on the pieces or cocoon under their thick, shiny finish.

The artist is famous for leading special guided meditations, often held in open, dramatic natural spaces. After claiming their attention by speaking through a microphone, he asks the attendants to close their eyes and concentrate on their breathing; then he starts reciting unique scripts that blend poetry and mindfulness. Additionally, he serves specially brewed drinks. With his artful meditations, Plessas directs the listeners to cosmological introspection: his words touch on various topics, including the beauty of biodiversity, the wonders of geology, the anxieties of living with others, and the sublime historicity of the universe. For this show, he printed a meditation on metallic paper and framed it on a wall. A quote from the poster beautifully reads: “As an ancestor or descendant, paternal or maternal elder or younger, sister or brother, deceased or unborn, we humans communicate and engage in relations of love, friendship, instinct, culture, intelligence but also ego, rivalry, suffering, ignorance. Where do we go from here? I inhale Thought and exhale Intelligence.”

Writing and speech are essential features of Plessas’ overall practice. At P.E.T., his spellbinding elocution can be heard soundtracking two videos packed with cogitations from his life philosophy. The first is called Technoshamanist Art Manifesto. Here, Plessas appears in front of a black backdrop, dressed in a purple three-eyed robe also exhibited at the show. The plot is minimal: the artist exposes the general intention of his practice, which is centered around the problem of harmonizing human action and its technological manifestations with a spiritual understanding of reality. Reading from an iPhone, he stands upright in the middle of the scene, resembling the leader of an unknown cult. Sometimes funny and unexpected Brechtian glitches intersperse the screen: Plessas takes himself seriously enough to be comfortable with self-directed humor.

For the second video, entitled Homo Noosphericus, Plessas decided to dub himself with an AI-generated voice he obtained feeding recordings to an online service. Here, a weird collection of GIF-like cut-outs unfolds upon a sublime background constituted by clips of planets, aurorae, abstract lights, and the starry night sky. Byzantine ivories, medieval marginalia, photographic portraits of North American natives, and monumental sculptures of famous historical men and women chase each other in a long dolly while the eccentric avatar of homo noosphericus walks, jumps, crawls, or stands on his head like a circus performer. A bravado of wit and fun, the experience of watching Homo Noosphericus reminded me of the excitement I felt as a kid perusing Microsoft Encarta, the nineties CD-ROM encyclopedia whose Internet-like structure of spiraling links and images could ignite anyone’s imagination.

The accelerated expansion of the intellect mediated by technological devices is a strong preoccupation for the artist. As the iconographic fanfare parades across the screen, Plessas’ AI voice expounds on the concept of noosphere. The artist discovered this idea through José Argüelles’ controversial 2011 book, Manifesto for the Noosphere. The Next Stage in the Evolution of Human Consciousness. Argüelles, an American artist and irregular scholar, was a prominent figure in the New Age movement. Among his bizarre accomplishments, one could remember the organization of the Harmonic Convergence—the world’s first synchronized global peace meditation—during a planetary alignment. Discontent with the modern understanding of health, he undertook a thorough examination of modern time scales. Investigating Maya calendrics, he ended up condemning the 60-minute hour—the rhythm of contemporary existence—accusing the Gregorian calendar of crippling human potentialities.

According to Argüelles, the noosphere represents a desirable tertiary phase in the history of planet Earth. This era followed the geological and biological ages. It began with the achievement of self-consciousness by the human species, and it is continuing towards the reification of the intellect via technical means. Argüelles traced the concept of noosphere back to the early XX-century writings of Russian polymath Vladimir Vernadsky and French theologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin. Teilhard de Chardin also developed the cognate idea of Omega Point, a teleologically necessary, supreme state of the cosmos towards which everything that exists is positively marching. In Teilhard de Chardin’s view, the noosphere –a modernist upgrade of the outdated idea of Divine providence—describes the force of human agency mediated by technology, which, given humanity’s foremost position in the chain of beings, leads the rest of the planet towards a progressive future.

One could draw parallels with Karl Marx’s notion of general intellect. Discussing the implications of social metabolism, in his 1858 Grundrisse, Marx argued that technology is an “organ of the human brain, created by the human hand; the power of knowledge, objectified. The development of fixed capital indicates to what degree general social knowledge has become a direct force of production, and to what degree, hence, the conditions of the process of social life itself have come under the control of the general intellect”. Such epistemology resonates with current issues raised by the fast development of artificial intelligence. Its same champions, like OpenAI’s CEO Salm Altman, fear that the outcomes of this innovation will exacerbate long-standing class divisions, partitioning humanity between those who control and operate governmental AI models and those who provide data for their training. Commenting on the situation, in the video Plessas’ AI litany goes: “We invented networks to divide what we connect.”

Today, in the wake of the ecological disaster and amidst a widening war for resources, the utopian thought that empowered the West from the French Revolution to the Second World War has ended, its spirit definitively buried under the heavy burden of the capital-induced permacrisis. Labile yet possibly inspirational notions such as those of noosphere and Omega Point are obscured by other, grim concepts such as the Anthropocene—the geological era characterized by the formation of artificial mineral strata—and the Singularity—a fantasized point in time in which a global network of machines will acquire self-awareness, supposedly determining the end of humanity. In such a panorama, Plessas’ explorations of eccentric outlooks, as unfashionable as they might sound, gift his audience with a great deal of optimism. In fact, for better or worse, the plethora of minority traditions he researches and esteems have all sought to devise a dignified standing for humanity. This vast heritage has been primarily concerned with the well-being of our species. Plessas expands traditional appeals for compassion to other living creatures as well as non-living entities—up to distant galaxies and down to quantum particles and the laws of physics themselves.

Do not hypothesize any gullible naivety operating in the spirit of the artist. Contrarian to any idle irrationalism or anachronistic cult of unworkable ideals, Plessas’ practice involves elaborating autonomous educational activities whose breadth and openness tease the void principles of multidisciplinarity too often advocated by academia. Over a handful of years, he developed five episodes of the Experimental Educational Protocol, a workshop program whose attitude towards the concept of education echoes Ivan Illich’s revolutionary theories on schooling. In the exhibition, one can leaf through a series of books documenting the workshops he organized convening artists, architects, poets, writers, and curators in multiple locations such as a Greek island, a sailing boat, and an Austrian art academy.

A significant artist’s statement lays out the Experimental Educational Protocol: “Education is the realization and the unfolding of the limitless potential of the mind. The teacher is an artist who helps the students shape their attitude from unrefined formless potential to a set of new experiences. Education unites us socially, politically, philosophically, culturally, and sometimes education and therapy are difficult to distinguish”. Sadly, today such principles seem to have been purged from many Western educational institutions, currently oppressed by ever-increasing and debilitating workloads of bureaucracy whose blatant scope is the incarceration of students and teachers behind the grids of a behavioral meritocracy devised by the ill world of management.

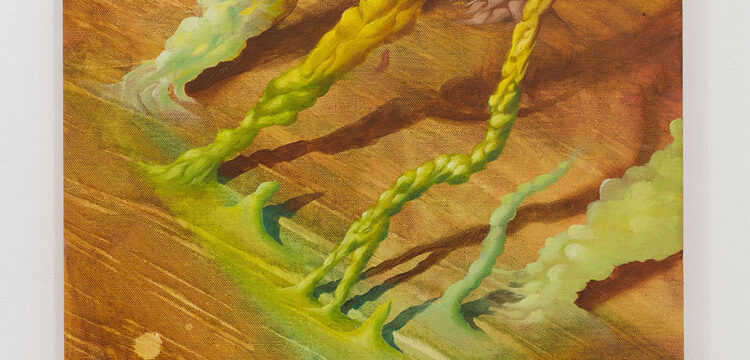

In an effort to oppose the status quo, throughout his practice Plessas consistently celebrates the real role of culture—from the Latin colere, a word related to agriculture and worship. In the exhibition, his ideals are illustrated by a quilt fashioned with vivid green branches growing inside the shape of a big head. The head nurtures the fruits of knowledge, represented by a bouquet of harlequin mandalas. Since culture does not only reside inside the skull of lonely individuals but is a set of actions and attitudes shared by groups, Plessas valorizes the multiplication of convivial opportunities. In Personal Explored Temptation, three photographs of a traditional ritual retell a crucial encounter set on the other side of the world.

In 2021, Plessas was invited to participate in South Korea’s Gwangju 13th Biennale. There he maneuvered to meet and collaborate with the local shaman Dodam, who shares his concerns about the ambivalent role of technology in contemporary life. The couple performed cleansing ceremonies together and visited a popular countryside stone monument that concentrates propitious energy. From the perspective of Plessas’ technoshamanism, transcendence and contemporary technology are closer than what one could expect. As a matter of fact, modern high-tech marvels provide each person with faculties once deemed exclusive of deities and demons. Digital communication mediated by the Internet provides faculties traditionally attributed to spiritual forces such as action at a distance, multilingual interaction, inexhaustible knowledge, everlasting memory, and numberless personhood through avatarization. On the other hand, the crystallization of global networks throughout state and military infrastructure equips contemporary power with unseen tools of enslavement and control unknown even to the devils populating Dante’s inferno: disinformation, drone warfare, citizen espionage, far-reaching financialization of goods and services, behavioral governmentality, deepfake impersonation.

Another outcome of Plessas’ activities in Gwangju is projected upon a curtain in the exhibition space. The image shows a dragon-like character giddily flying on top of a minimalistic flat background. The creature moves around, planting colorful circular seeds sprouting clipart-like flowers, shaping a virtual garden. Glimmering, scattered sounds conjure a casual Zen atmosphere. These images come from the website everyoneisyou.com. Since more than two decades, the artist codes animated, frolic domains. According to Plessas, these compositions coalesce influences stemming from ancient iconography, modernism, experimental music, and drawing. Everything is playable on your computer through the links he compiled on his homepage. A collection of amusing pockets with dreamy titles (HomoEthericus, LeVoyageDeLaLune, HorizonPerdu…), Plessas’ websites sing a merry symphony to the joy of creation while claiming Internet servers as a suitable location for timeless artworks.

Personal Explored Temptation is closed by two monumental pieces, the Quilt of All Beings and Homo Noosphericus. The themes of these banners reflect Plessas’ late enthusiasm for the non-human and non-technological, in the direction of a concept of nature that welcomes the most generous number of entities. These artworks present two humanoid avatars traced upon a black background. Their bodies are constructed with symbols and shapes as diverse as a Wi-Fi icon, an orange rabbit, a red mushroom, a U.F.O., a lotus flower, and a peace sign. With their composite, intermixed bodies, the quilts visualize an imaginative, sought-after contemporary definition of humanity that refuses homogeneity, deliberate violence, and ruthless sadism while calling for heterogeneity, jolly openness, and universal piety.

Far from rejecting Plessas’ overall message as utopistic or childish, in a time of global political regression fueling nationalisms and horrific wars, we must vow to the artist’s principles and affirm the necessity of a peaceful revolution. This contemplative uprising moves from the renegotiation of the self towards a conscious approach to the world. The exhibition raises manifold unexpected questions: can we imagine being gentle with our machines? Can we elevate our devices and communication networks to the status of living, spiritual beings? Can we envision a harmonious integration of everything within a global, inclusive framework, eliminating the tribal traditions of supremacy embedded in the linguistic, political, economic, philosophical, and familial institutions we inherited from our ancestors? Much work is still to be done, but Personal Explored Temptation offers Plessas’ ideas to achieve a communal enlightened progress.

Ultimately, the act of “giving oneself a six-year retrospective” inscribes itself in this tender rebellion against the given. Recasting Argüelles’ critique of time, rather than waiting for any institutional retrospective to happen in any biennial, triennial or quinquennial art exhibition, Plessas emphasizes the need for every person—not just artists—to engage in a moment of biographical self-reflection at any interval of time they deem necessary. Plessas invites everyone to shape the living space they occupy with a personal, distinctive touch, and to open each house (and each mind) to the difference brought by the other—be it a pet, a friend, a fellow artist, a machine, a plant, a microorganism, a weather phenomenon. Dismissing any gnostic approach between sacrality and rationality, the art of Angelo Plessas affirms the importance of building and multiplying joyful temples dedicated to the well-being of ourselves and our world at large.