Performing Care Work

Maintenance/reproduction vs Development/production and the “phantom” caring body

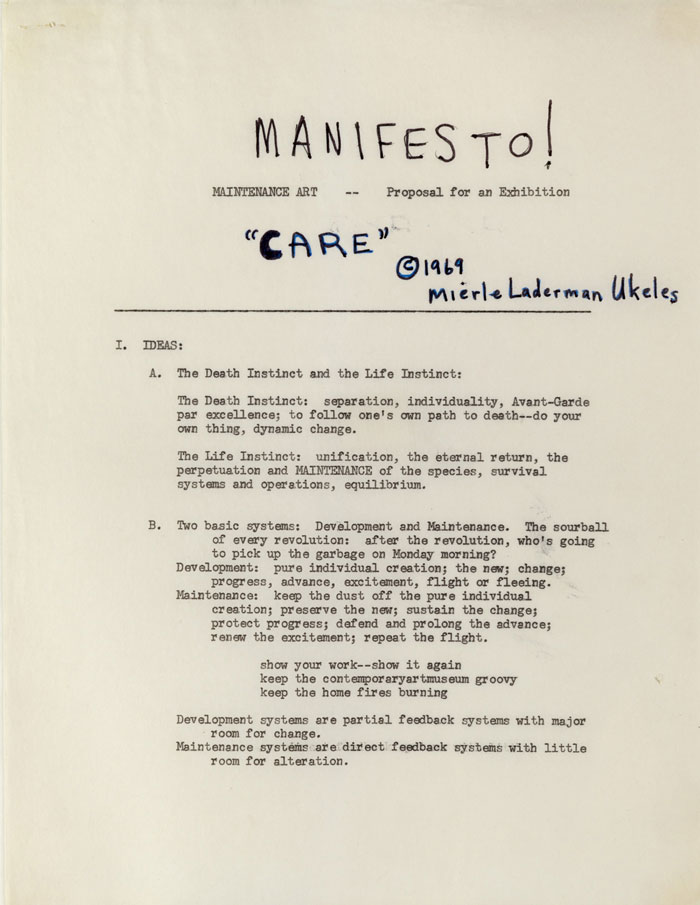

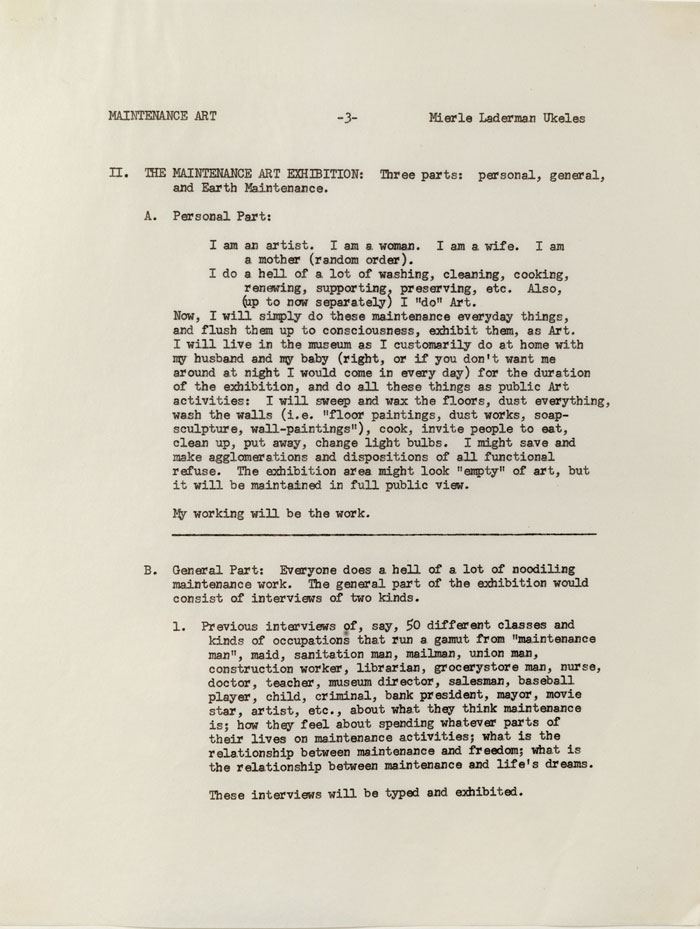

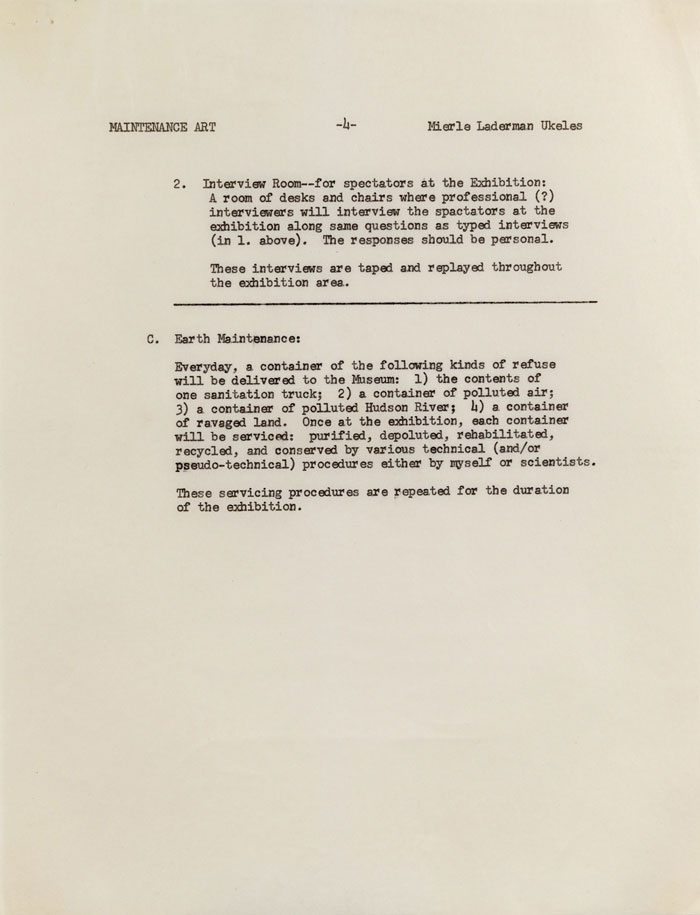

Whilst still a student, at the height of artistic experimentation, American artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles (b.1939) fell pregnant. She recalls entering the classroom of a renowned sculptor who looked at her protruding stomach and announced “well, I guess now you can’t be an artist.” After having a baby, she remembers, “I had no models, none, in my entire education to deal with repetitiveness [and] continuity.” Unprepared for the astounding monotony of childcare, Ukeles suffered a crisis: “I no longer understood who I was. I got so pissed-off. I became utterly furious at not feeling like one whole human being”; “I felt like I was two completely different people”; “Half of my time I was The Mother….And half of the time, I was The Artist.” This crisis prompted a radical reconsideration of her model for working. In a single fury-fuelled bout of inspiration Ukeles produced Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969! and Proposal for an Exhibition: “CARE”, declaring all maintenance labour (both in the domestic sense and as a public service) Art, a gesture that sought to expand Marcel Duchamp’s idea of the readymade, whereby not only found objects may become art, but also found actions, habits and everyday activities.

Ukeles described the original manifesto as “a structure that is actually a sculpture, though it looks like a text,” situating her manifesto between artistic manifesto and conceptual artwork. Through the production of this manifesto, Ukeles made an extraordinary discursive shift in her art practice that would thenceforth link her experience as a mother with the struggle of the (maintenance) worker: “it’s as if I looked up suddenly, after all my formal education in autonomy, and I saw people doing support work, to keep something else going, and not necessarily only themselves. Workers.” In a now canonical feminist gesture Ukeles performed her Maintenance Art at Wadsworth Athenaeum in Hartford in 1973 as part of the all-female exhibition c.7500 curated by Lucy Lippard.

With the reconsideration/reinsertion of reproductive labour into the writing of Art History, especially (feminist) Art History from the 60’s and 70’s, whose crucial engagement with social reproductive labour was lost to semiotic and psychoanalytic (Lacanian) readings privileged within art historical discourse at the time, Ukeles’ Maintenance Art has reemerged as an important cultural archive through which to consider issues central to social reproduction theory and the intellectual production of Marxist feminists associated with the Wages for Housework (WfH) Campaign that emerged in Northern Italy during the 1970s, that denounced issues related to the devalorization of reproductive labour, the relationship between paid and unpaid work, and the ways in which this distinction is organized around binary constructions of gender.

It is important here to stress the historical situatedness of Ukeles’ (and WfH’s) critique as it is confined to a post-war, Fordist economy and the figure of the housewife. In Proposal for an Exhibition the artist writes that the performance “would zero in on pure maintenance, exhibit it as contemporary art, and yield, by utter opposition, clarity of issues.” The “utter opposition” the artist refers to is set up by transposing invisible feminized labour, normally performed in private, onto the public sphere. By performing housework as art, by hauling the domestic sphere into the art museum, the artist exposes what Marx refers to as “the hidden abode of reproduction,” or, as Leopoldina Fortunati terms in her book by the same name, the “arcane of social reproduction,” given that it is “even more hidden as it is gendered, unmonetized and assigned to the ‘private sphere.’” Through this displacement, what is usually a functional activity becomes a purely formal gesture, which plays into an art practice that seeks to disrupt the separation of art and labour.

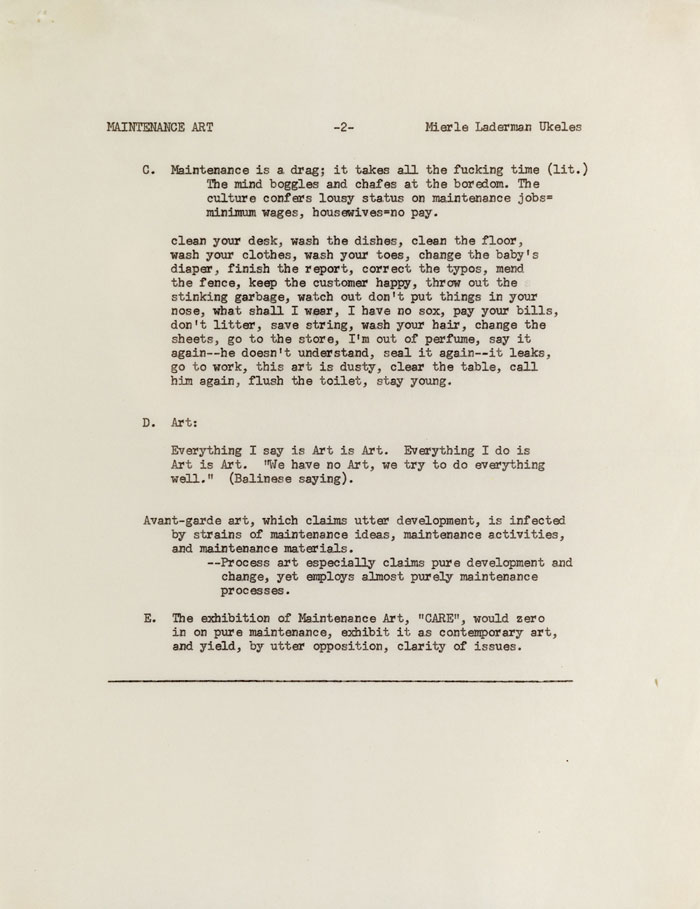

By discussing the housewife in regard to wage relations, or a lack-thereof, the artist radically denaturalizes domestic labor. In her Manifesto she writes “maintenance jobs = minimum wages, housewife = no pay.” The statement’s critique is twofold. On the one hand, the public maintenance worker and housewife are united through the devaluation of their work, perceived as non-productive, and the inferior social position they occupy within the population. However, the housewife is recognized as being exploited by capitalism to an even further degree, for she is completely outside the dynamics of wage relations. Although the maintenance worker and housewife both perform subaltern forms of labour, one has a wage around which to organize: “the wage at least recognizes that you are a worker, and you can bargain and struggle around and against the terms and the quantity of that wage, the terms and the quantity of that work. To have a wage means to be part of a social contract, and there is no doubt concerning its meaning: you work, not because you like it, or because it comes naturally to you, but because it is the only condition under which you are allowed to live. Exploited as you might be, you are not that work.”

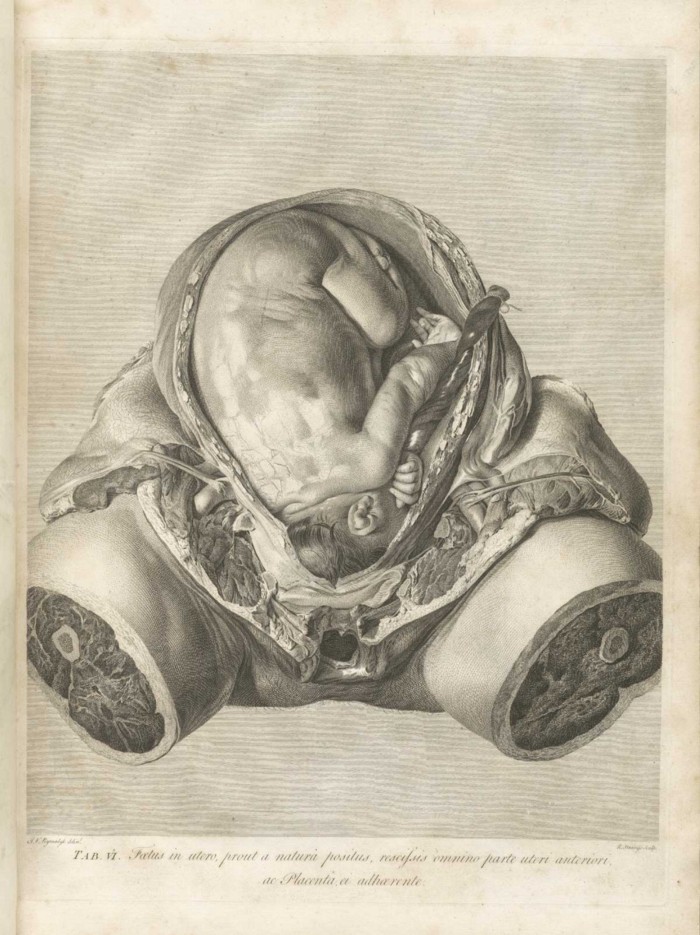

The difference with housework, therefore, resides in the idea that not only has it been imposed and enforced upon the category woman, but it has been made into a “natural attribute of our female physique and personality, an internal need, an aspiration, supposedly coming from the depth of our female character.” There emerges a tightly bound dialectical relationship between the abstract conceptions of femininity—be it the all-giving and all-loving wife and mother, the conviction that it is in women’s nature to care for those around her, or the insidious refrain of “women are better at multitasking”—and the concrete and material realities of her burden.

In Silvia Federici’s major intervention Wages Against Housework, published in 1975, she argues that “housework was transformed into a natural attribute, rather than being recognized as work, because it was destined to be unwaged. Capital had to convince us that it is a natural, unavoidable, and even fulfilling activity to make us accept working without a wage.” Marxist feminist thinkers sought to address a vital lacuna in Marx’s theory of capital. Whilst classical Marxist analysis privileges production, feminist theories developed since the 1960s have been preoccupied with the neglected process of reproduction. That is, a specific set of tasks, physical and emotional, such as childbearing and child-rearing, cooking, cleaning, washing as well as sex and emotional care, have traditionally fallen to precisely the category woman. Women’s unpaid reproductive labour was thus recuperated and recognized as a key source of capitalist accumulation. The key expansion into Marx’s theory of capitalist production was the claim that reproductive labour, rather than being outside of value production, is central, and absolutely necessary to the generation of profit. It is for this very reason, Marxist Feminists claim, that housework is devalued: its naturalization and invisibilization are necessary to the continuation of surplus value. In Federici’s words, “capitalist accumulation is structurally dependent on the free appropriation of immense quantities of labour and resources that must appear as externalities to the market, like the unpaid domestic work that women have provided, upon which employers have relied for the reproduction of the workforce.” This would suggest that the category woman has been produced as a devalued and exploited section of the population as a means to prop up capitalism and allow for the generation of value.

What Ukeles terms “Maintenance” can be mapped onto the Marxist feminist optic of reproductive labour. In section B. of Manifesto Ukeles sets up an opposition between the “two basic systems” of “Maintenance” and “Development”. Although the gendered implications of the two paradigms are not explicitly alluded to, there is a sustained division and hierarchy throughout the text that echoes the division and hierarchy of feminized, reproductive labour, and masculinized, so-called productive labour. Whilst the lexical field generated by Development evokes radical individualism and self-sufficiency: “pure individual creation; the new; change; progress; advance; excitement; fight or fleeing”, the terms evoked by Maintenance merely qualify, elevate and uphold the system of Development. In fact, the constellation of verbs relating to Maintenance is merely offered as an appendage to the former masculinized category: “keep the dust off the pure individual creation; preserve the new; sustain the change; protect progress; defend and prolong the advance; renew the excitement; repeat the flight.”

What is crucial here is that Development and so-called “pure individual creation” cannot take place without its necessary maintenance. The antagonism between the two terms certainly mirrors the contours of the gendered division of labour that separates production from reproduction. As Fortunati writes, “the first appears as the creation of value, the second, reproduction, appears as the creation of non-value.” However, despite “their seeming separation, the capitalist mode of production is based on the indissoluble connection that links reproduction with production, because the second is both a precondition and a condition of the existence of the first.” Crucially, “production work is posited as being work involved in commodity production (wage work), reproduction work is posited as a natural force of social labour, which, while appearing as a personal service, is in fact indirectly waged labour engaged in the reproduction of labour power.” Whilst Ukeles presents “Two basic systems” she performs a discursive technique that acknowledges they are not autonomous or mutually exclusive from one another; that Maintenance/reproduction is indeed “the precondition and a condition of the existence of” Development/production.

Ukeles recounts in a stream-of-consciousness style a series of mundane, prosaic tasks that she forcefully reminds herself to perform on a day-to-day basis, such as; “pay your bills, don’t litter, save string, wash your hair, change the sheets…” The use of the imperative mood would usually imply a second-person subject. However, given that it is an internal monologue that evidently reflects the author’s own thought-processes, there is a distancing effect between subject and author that creates an overwhelming sense of the author’s alienation from herself and her own actions. The subject’s so-called interiority is exposed as being entirely constituted by self-regulating, self-disciplining orders, which recall the subject of Michel Foucault’s disciplinary regime. As capitalism became the dominant organizing principle of society, a new form of power emerged; one which, rather than subjecting the masses, would enlist them in the service of their own subjection. Scientific discourse being developed around the body at this time, along with developments in technology, gave way to what Foucault terms as political anatomy or a machinery of the body, that is, the minute anatomical analysis and breaking down of the body, so as to control it both in space and time, and use its force most effectively. In this way, as illustrated through the intimate, yet disconcerting, self-disciplining, self-punishing monologue written by Ukeles, the subject emerges through the abstract system of power that is the Foucauldian disciplinary regime, that forms bodies to be obedient, efficient, and useful to capitalist production. Ukeles’ rambling self-interpellations reflect the rigor of the subject’s work ethic. As Kathi Weeks writes in The Problem of Work, the imaginary of the work ethic, more “than an ideology…is a disciplinary mechanism that constructs subjects as productive individuals.”

To bring the discussion into the present, since Ukeles first performed her Maintenance Art in 1973, theories of reproductive labour have adjusted to the financialized, neoliberal economy and global labour flows. In the wake of the women’s liberation movement in the United States, which heralded a massive increase in women entering wage-relations and the workforce outside of the home, the burden of reproductive labour has shifted to the Global South, which presents an available labour pool to perform cleaning/care work for households in wealthy countries of the capitalist core. As a result, recent materialist feminist analyses tend not to look at unpaid forms of work, but rather its paid forms outside of the home, “bringing into visibility the technologies of racialization and illegalization that prop up accumulation through the economic and social devalorization of (the labour of) many, if not most, of the global population.” In her essential essay Capitalocene, Waste, Race, and Gender published in e-flux journal May 2019, French decolonial feminist scholar Françoise Vergès discusses the racialization of cleaning/care work today and how this is embedded within the wider context of the environmental history of colonialism, the gentrification of cities and green capitalism. Vergès reworks feminist theories of reproduction by mapping the dialectic of the visible white “male performing body” and the invisible “racialized female exhausted body.”

In the 1970s, she writes, “as white feminists denounced the boredom and invisibility of unpaid housework, the movement to recruit racialized women for cleaning/caring accelerated.” As women of the North Atlantic entered paid jobs, these tasks were viewed as an unwanted hangover, incongruent to the image of the modern woman. Today it is the labor of black and migrant/refugee women states Vergès, that is invisibilized and naturalized in order to sustain neoliberal and patriarchal capitalism as to ensure that the “[upper] class, white, neoliberal, and even liberal people must enter these spaces without having to acknowledge, to think of, to imagine, the work of cleaning/caring.” The performing male neoliberal body, in this sense, has a “phantom” body that enables his inexhaustible productivity. Meanwhile the female racialized body circulates within an economy of exhaustion, that is the consequence of the historical logic of extractivism extending from colonial slavery and the labor extracted from racialized bodies for primitive accumulation.

Vergès frames the mining of bodies within the growing anxiety for cleanliness—clean eating, green spaces, clean air, clean bodies etc. This appetite for a healthy mind and body specific to late capitalism, most recognizable in gentrified areas of the big metropoles of the world is built on New Age ideologies of the 1970s which appropriated Eastern and indigenous cultures and practices. “It has developed into a major and lucrative market, offering meditation and herbal teas, yoga and exotic whole grains, gyms and massages for every age, founded on class privilege and that very cultural appropriation”—the final aim being “personal efficiency and the maximization of productivity.” But whilst Western capitalist centers engage in blind consumerism disguised as clean or green living, they pass on their waste onto the countries of the Global South, perpetuating colonial histories that saw the laying waste of people and lands that it colonized.

As Christian Marazzi writes “feminism of the 1970s made a huge contribution to the crisis in Fordism, but also laid the foundations for a whole range of differences other than that of gender.” As relations of production reorganized in order to enter capitalism’s next phase, so too did the relations of exploitation, which is why there is a continued urgency for a theory of care work that responds to changing economic structures, environmental catastrophe and colonial legacies.