New Epistemologies of Togetherness

Contemporary methods of collective works developed by artists’ formations, inspiring new strategies of human interaction

We went to see the exhibition Peer-to-Peer, curated by Agnieszka Pindera for MS2 in Łódź. We met Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff, who were there to see their Apartment play readapted by the local artist collective Dom Mody Limanka. Here is what we witnessed.

Reviewing an exhibition like Peer-to-Peer on your own sounds like a contradiction. It feels like it should have been done collectively, at least as a dialogue. So you would limit yourself in telling what you saw, and just report what you have encountered and witnessed. You would recount the visuals and deliver them through the help of images, and share contents and visions through the voices of the people you have met. The artworks in Peer-to-Peer are all results of a shared effort, in their delivery, they cannot prescind the context in which they were made.

Peer-to-Peer, Installation view. Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Indeed, Peer-to-peer is a show about collective practices, and in a way about modes of conversations and of conceiving the world, based on contemporary models of collectivity. Nowadays, being together does not necessarily correspond to physical proximity, but it is more like an intention, or an announcement. Working together is an urgency, that pushes persona to meet beyond spatial limitations. In some cases, Whatsapp replaced the bar. In some others, the bar replaced the theater. But the collective practice can still come out as bold as an avant garde. Either by a duo, a delegation, a platform or a working group, collective practice demands dialogue and negotiation, which consequently result in making the object produced inherently political. At least this is what this exhibition demands us to reflect upon. What does it mean to do things together, beside being together? The possible answers to this question, materialized as outcomes, are several, and probably the stories behind the objects are as relevant and material, because in a sense, they already stand out as histories.

But then also, what does it mean to frame these practices within a white cube? To narrate them in the museum? To have nine artworks for almost forty artists? What are the implications for the curatorial economy of the museum? How does it affect the singular subjectivities of the audience? Why today, and why in Poland?

Collective practices come out as statements, that is probably why they trigger so many questions, and their objects behold a significance that surpasses their geography. They are discursive experiments constructed on rules—whether defined or not—therefore become applicable elsewhere, transposable to be used and adopted by others. They lack the touch of the singular human, and the way they came into being is maybe more relevant than their final form, and they can thus hold on to their narrative, rather than to their name, signature or brand. In most cases, the artworks that Peer-to-peer delivers are models and modes of reflection.

Peer-to-Peer, Installation view. Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Whilst the title of the exhibition bears reference to the peer-to-peer network’s method of communication, that opened the way to new strategies of non-centralized human interaction, the curatorial approach divides the collective experiences in three thematic sections related to a range of contemporary phenomena, such as work/efficiency/future, internet/affect/being together, and technology/emancipation/migration. What collective practices and peer-to-peer infrastructures have in common is that they rely on self-management and self-organization, and play an essential role in contemporary society. The urgency to bring together these modalities was triggered by the research of Polish economist Monika Kostera, who argues that almost everyone today is familiar with the basics of management, and therefore is time to tap into that knowledge to create new intermediary organizations, with different goals from main corporations and political forces. In a phase of an interregnum, in-between systems, she suggests it is important to value and cultivate sustainable relationships and new epistemologies of togetherness—both financial and human—to contrast the current power structures and political settings. The collective practices presented in the exhibition wish to stand as possible responses to this call.

The first encounter is the most shining one, a semblance of self-celebratory luxury. GCC trophies and summits tables painting floating on the gallery wall are at first tricking us into a gulf-like kitschy aesthetics, although too contemporary to be authentic. It initially felt like I didn’t get the joke. Like many other collective works, the pun is made among members, so you need to know them first to get it. So, GCC is a “delegation” of 8 members, who all have strong ties to the Arab Gulf region but live between Kuwait, New York, London, Berlin and Chiang Mai. The name GCC alludes to the Gulf Cooperation Council—the intergovernmental political and economic partnership among six countries of the region. Instead, the artist collective was founded in 2013 at Art Dubai, and has focused ever since on the systems of power in the Gulf region and abroad, making use of objects typical of public administration and motivation strategies, borrowing customs from the business world and politics both for their artworks and their mode of self-management. They refer to themselves as delegates, communicate mainly on Whatsapp always adopting a corporate language and every once in a while meet for “summits.” The congratulatory words expressed by the Department of Trophies and Congratulation—operating within GCC—shine on the engraved inscriptions of the Congratulants (2013), exposing “success propaganda” and corporate culture’s mechanisms. Behind them, the hexagonal table symbol of GCC’s gatherings on the oil paintings is an embodiment of bureaucracy and mutual relations between power and authority.

Peer-to-Peer, Installation view. Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Then the work of the duo signed with the acronym BNNT—which started with sound performances in public and institutional spaces, and from 2013 began to create audio-visual installations, crossing borders between music, visual arts, theater, stage performance and dance—is an immersive installation, conceived as a music video for one of their most recent album. In MULTIVERSE / Consider a Single Wave Relieved the Pressure on the System (2018), the video footage portraits unaware drivers stuck in traffic jam projected on five different walls, as the soundtrack is also distributed through a multi-channel sound system, giving an unusual tridimensional quality to the chosen medium. The demand that the work makes to walk around it, triggers a feeling of fragmentary alienation, like we could be in this all together if we’d want to.

The installation by the Pakui Hardware duo is inspired by body modification and technological innovations, fitness and bioscience, despite it gives the feeling of a sci-fi/outer space landscape, where surfaces resemble cyborgs’ epidermis. Composed with NASA images, food colorants, chia seeds and silicone, the piece is titled On Demand (2017), as reference to goods availability and contemporary work environment. The group overall practice focuses on automation and efficiency, as expressed by their name, which bears reference to a Hawaiian myth concerning fragmentation and acceleration, in which Pakui was the extremely quick servant of the Hawaiian fertility goddess Haumea.

Peer-to-Peer, Installation view. Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

The trio LaBeouf, Rönkkö & Turner presents participatory performances investigating the humanism and intimacy of the Internet, while experimenting with platforms of communications with the audience. Their projects have a pre-established duration, during which agency is given to the audience, upon open-ended invitation. The video #takemeanywhere (2016) documents a month-long journey, during which the artists shared their location online on a daily bases with the hashtag #takemeanywhere and invited the audience to pick them up and take them wherever they wanted. The platform used was the website www.take-me-any-where.com where one could follow their path on real time. The film shows some of the people they encountered during the trip, which took place in North America during the 2016 presidential campaign. For Peer-to-Peer, the trio brought also their long-term project titled hewillnotdivide.us, initiated for Donald Trump term of office in 2017 as a form of resistance to the negative effects of social polarization. Previously existed in various forms in several institutions and locations, the Łódź iteration consists of a camera installed on the MS2 facade, live-streaming on the website www.hewillnotdivide.us, where the audience is invited to freely engage with the message “He Will Not Divide Us.” From its outset, the work has often been targeted by extremist neo-Nazi bullies, delivering violent messages in rejection of its initial goal. In Łódź too, the camera has recorded some antagonist feedbacks. This is an example on how the proposed model, carried by the work political statement, takes risks in engaging with—and being adopted by the other.

Part-time Suite is a collective from South Korea, interested in fields such as urban planning and management, precarious work and online environment. They initially engaged with dismissed urban spaces, such as industrial buildings’ basements and rooftops, which were used as venues and studios, generally preferring physical work and activities associated with light industry over object-production, connecting the ephemeral worlds of artistic practice and work economy. The video Toloveruin (2017) is inspired both by demonstrations in Kyoto and love relationships. We see alternatively footage posted on Youtube both by racists and partisans for propaganda purposes, and two lovers following the protests’ routes and images recorded on the same routes using a motion detector. The soundtrack is a mix between the lovers’ discourse, insecurity and frustration and the Kinetic motion detector instructing the user.

Peer-to-Peer, Installation view. Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Foundland Collective is a duo that was formed in 2011 in Amsterdam and combines design, research, visual arts and education to explore matters of migration, belonging and citizenship. The presented work Scenarios for Failed Futures (2015) is a record of Yassin Elsrakbi (one of the members’ father) and his wife’s reflections about their homeland Syria, wherefrom they were forced to leave in 2013. Past and future subjective perspectives and narration of facts are accompanied by a sterile, quasi-corporate graphic visualization of the geopolitical dynamics of the region, through 3D maps and infographics.

NON Worldwide is a platform serving artists from the African diaspora—a global borderless non-state that aims to create a space free from colonial structures and the ossified conventions of self-expression. The platform employs aesthetics between corporate identity and internet culture, and acknowledges the power of branding, in terms of representation, message and circulation. The NON Worldwide brand presents material from the latest trilogy, a compilation featuring the work of 42 members, who used sound as a medium to draw attention on issues of violence, detention, queer and black identity. As the music goes on for hours, the space has been made comfortable to stay and indulge, although everything is also to be found online.

Peer-to-Peer, Installation view. Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Peer-to-Peer, Installation view. Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Laboria Cuboniks—anagram of Nicolas Bourbaki, a collective of french mathematicians active in the 30s—define themselves as a working group that values the multi-vocality of the transdisciplinary projects and promotes a techno-materilistic and anti-naturalistic version of XXI century feminism. They are most known for their Xenofeminist Manifesto, which was first proclaimed online and translated into twelve languages, and has just been very recently published by Verso. The work featured in the exhibition Updates-updating-update (2017) is a 3-channel video installation, delivering a visual lecture on artificial intelligence and post-humanism, produced in a promiscuous mode and compiled from different sources.

Finally, Calla Henkel & Max Pitegoff’s stage, usually hosting a prop and the script (with the Polish translation) of their New Theater‘s plays Apartment and Farming in Europe. The former has been handed over to the very young collective based in Łódź, named Dom Mody Limanka, first to be turned into a public reading, but eventually allegedly reworked for the context it was destined for. And the result was brilliant. I could indulge in describing the stage, the costumes and props, contextualizing both experiences of the New Theater and Dom Mody Limanka. But instead I’d rather simply report the conversation that happened after the performance, accompanied by the polaroids taken by Anna Zagrodzka.

Peer-to-Peer, Installation view. Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Agnieszka Pindera: What was New Theater? Was it an artist run space, a project, a community? Especially now looking back after few years that it has been gone?

Calla Henkel: It was very much a space. Max and I do a lot of performance work and we had been frustrated by performing in galleries and institutions, where the audience is not given a clear role in terms of how to watch. So, we became very interested in the structure of the theater, as this sort of place for hierarchies and rules, where the audience feels allowed to just sit down and wait for a performance to happen.

Max Pitegoff: We’re both artists and we don’t come from a theater background at all, so we opened the theater in the vein of an artist run space, but we were interested in pushing the boundaries of what a typical exhibition space could do.

Calla Henkel: Yeah, so we would write about one play a month and then invite different artists, a mix of people, to either bring their work in, or write, or act. Someone would show something in a gallery, for example, and then we would ask if it could become a set piece or a prop. Works were constantly getting used and reused. In this way the plays created a moment where all these disparate pieces and people were forced to work together for at least the one hour of the play before they returned to their own autonomy. It was this sort of forced collectivity that we were interested in, that theater allowed, maybe more so than a group show or more so than a strict performance work, where everything is separated.

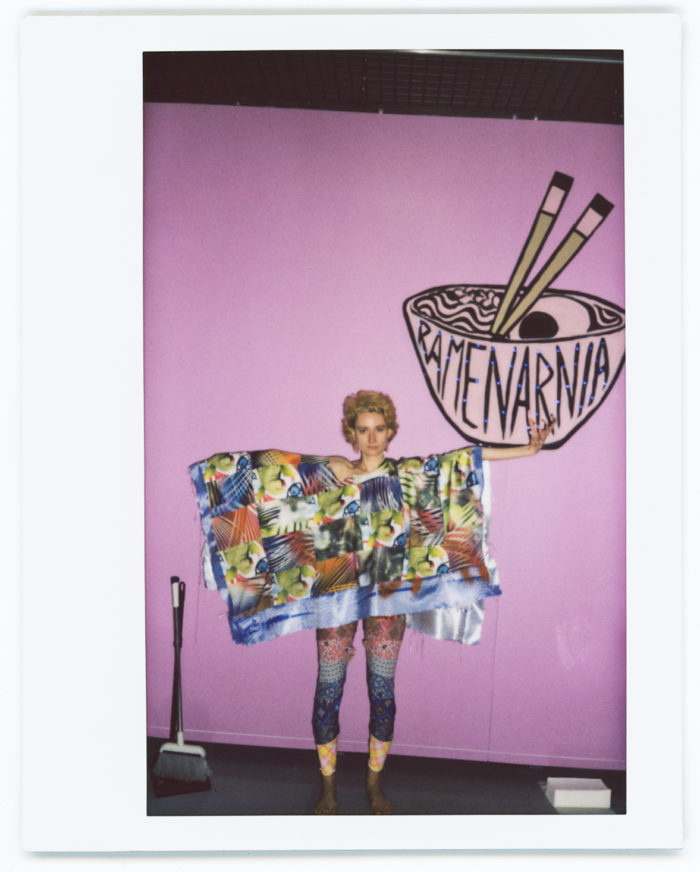

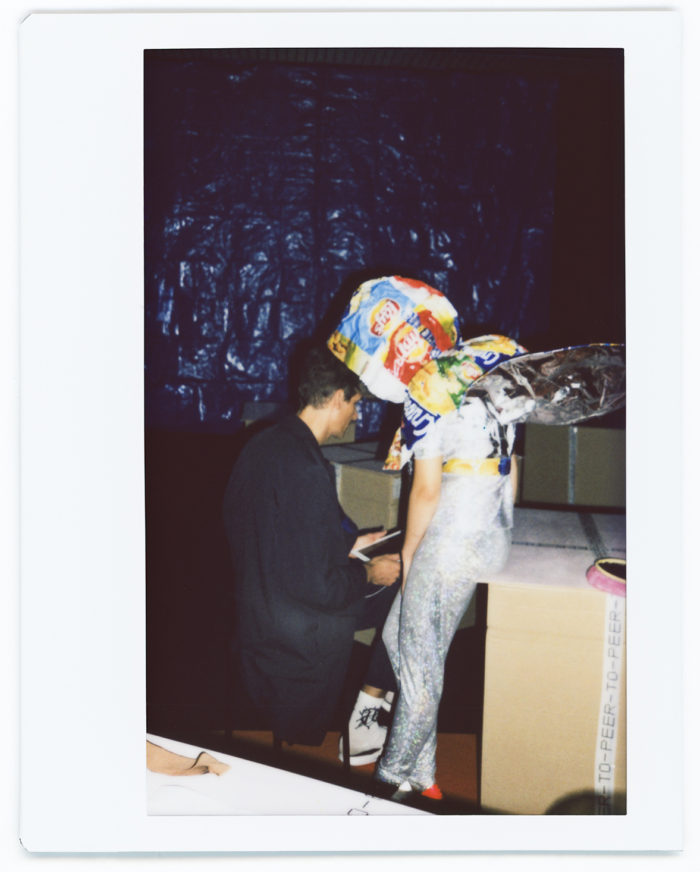

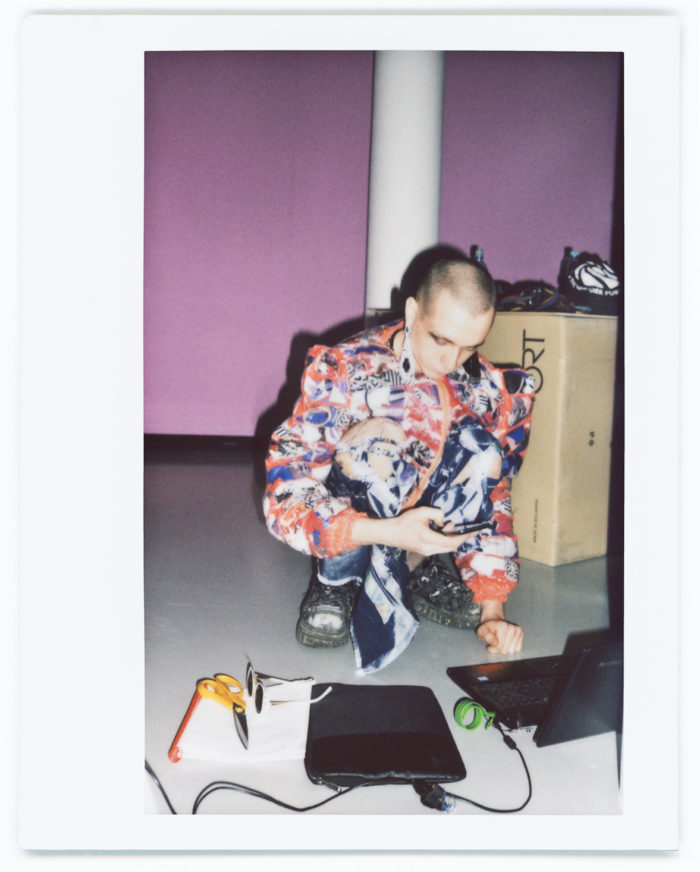

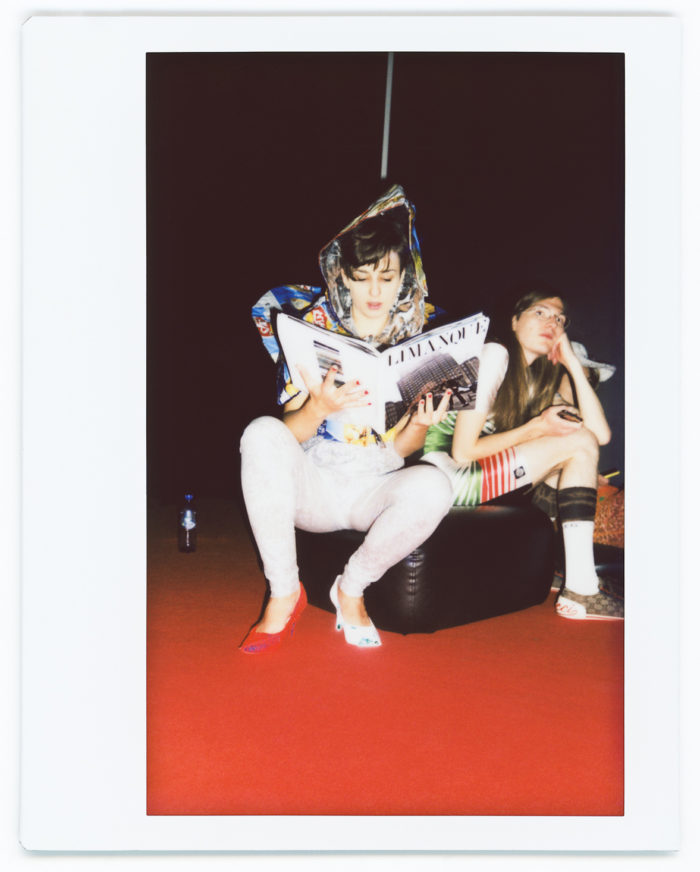

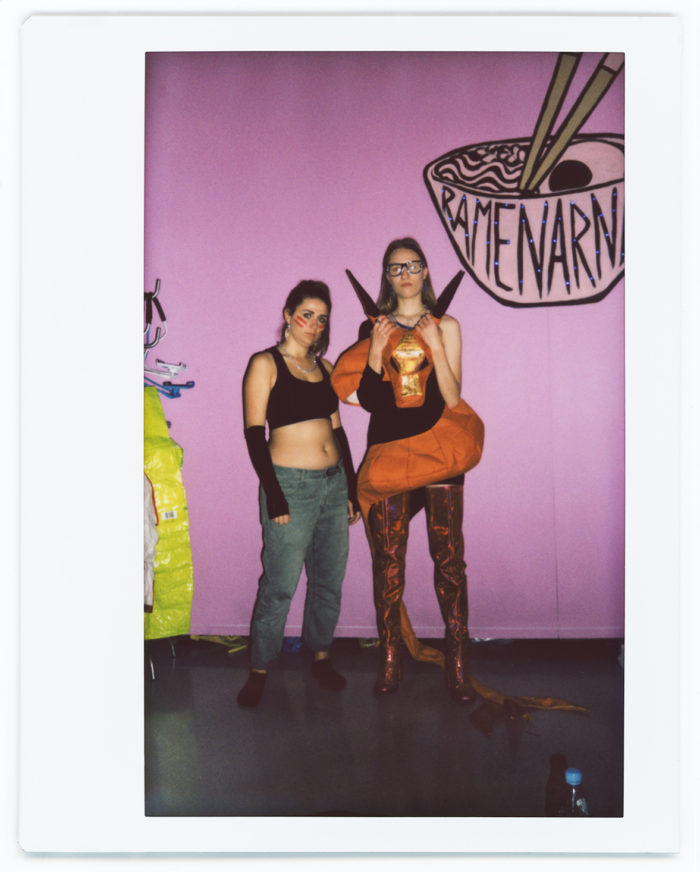

Dom Mody Limanka, Apartment (original script by Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff). Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Max Pitegoff: As the project grew, a kind of collective — or actually, a theatrical language grew out of it, in a way. But it was very much in the vein of of amateur performance.

Calla Henkel: We never worked with professional actors, which is something we were really interested in. That’s why it’s so nice to watch how you guys work through this play. We were really interested in artists to also perform the text alongside the objects they were making, so the performances had this kind of clunkiness to them. There is something very intense about watching someone who you know on stage — it’s heartbreaking, and you’re both embarrassed and excited for them. There is a type of gasoline in that sort of performance that I think is so different from watching someone who is really profesional at performing. This crunchiness is something we tried to keep up, which is also part of the speed of it. You watch everyone depend on each other in this way, which is exciting, but almost always also looks like a kind of collective trauma. That was the ethos of New Theater, to continue to build these plays that were also trashbags for ideas and works and thoughts, and then to be able to move on quickly to the next.

Agnieszka Pindera: Could you share a bit more on this particular piece, as the authors of this piece? What was the context it was born into?

Calla Henkel: This is a play that came out in the middle of working on a collective project.vI think that everyone who works in a group knows that there are different roles that you fall into and play off of, and I think this one came out almost overnight. In a way we were like—ok, you have all these fantasies about what you’re doing and you can build this castle of language and political ideals, but what is actually happening inside, in the trade-offs and concessions you have to make with your own morals in order to keep on going, which is, for them, the Ramen place. They wanted something different from what they end up with. But at the end of the day they all still have each other. We always talk about this thing where collectivity or locality are going to save us from global catastrophe, and global warming is this one thing where I am not sure if those things can save us. This play holds this kind of trauma between some giant problem and the little umbrella that you can make to protect you and the ones you care about. It’s moving in and out of these politics, which I think are really important but also unstable.

Dom Mody Limanka, Apartment (original script by Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff). Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Max Pitegoff: This was I think the fifth play that we had made, out of something like twelve in total at New Theater, and it was the only one that Calla and I authored on our own, but at the same time the actors we worked with changed the text and narrative completely. It really became this collective text, which ended up in the final script we made, and also continued to change as you guys were doing it…

Calla Henkel: It’s so nice to hand this off, because we really believe in collective editing. You write for people knowing who they are and what they can pull off. If you’re not an actor you cannot say—yes, I’ll play Diana Ross—if you’re not willing to play Diana Ross. People have their limits, so we would write for them and then allow them to push and pull themselves within their characters. So it was really nice to have you guys take them, and continue that, allowing them to get further from the text and closer to something that makes sense for you guys.

Dom Mody Limanka, Apartment (original script by Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff). Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Agnieszka Pindera: And you guys—Dom Mody Limanka, I am curious about both your first impression and about the process, how decisions were taken, who would be playing what?

Dominika Ciemięga: We were inviting our friends to participate. The criteria was the ability to read. [laugh]

Tomasz Armada: At some point we ran out of people to invite [laugh]

Sasa Lubińska: Actually the main characters were pretty easy to cast. For instance Kevin is a character running around the house, yelling that the lunch is ready and served. This is exactly what Kacper (Kacper Szalecki) does in our flat, as he is the one cooking for all of us.

Dominika Ciemięga: We were simply meeting to read together, at first each of us had a part selected for themselves, and as we were going we would find out what character would fit to whom, if each of us would be able to interpret it, and if he or she would feel like doing so…

Dom Mody Limanka, Apartment (original script by Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff). Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Agnieszka Pindera: Was it easy to adapt? How did you manage to include all the local places—and context into the play?

Tomasz Armada: It was quite easy and natural.

Monika Dembinska: I didn’t like the Polish translation to be honest.

Tomasz Armada: Monika was editing it…

Monika Dembinska: For instance the word “fucking” appearing in original script was translated in the Polish version as ”freaking.” No one says that. Maybe it is not the best example, but we felt we needed to change some words in order to better reflect the way we really speak.

Sasa Lubińska: The main twist was the location. The original play was describing events in NYC, in the US…

Dominika Ciemięga: Very far from us…

Sasa Lubinska: So we changed it so that it’d take place in Łódź…

Dom Mody Limanka, Apartment (original script by Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff). Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Audience: What about the costumes? Was there a description, like a clue or inspiration in the script itself?

Tomasz Armada: There was no direction for costumes in the script. I selected some items from different designers. Kacper (Kacper Szalecki) produced some special jewelry items and together we made some of the costumes. And Pamela (Pamela Bożek) was wearing her own sculpture.

Dominka Ciemięga: Some designs are mine…

Sasa Lubińska: How actually crazy were the costumes made for the New Theater version?

Calla Henkel: Our costumes were only made from denim. We worked with Nhu Duong, who’s a fashion designer in Berlin. She created these amazing assless denim chaps…

Max Pitegoff: She got as much denim as she could and compiled and constructed tons of costumes, and we all grabbed the ones we thought our characters would wear.

Dom Mody Limanka, Apartment (original script by Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff). Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Monika Dembinska: I think it is important to add that we haven’t seen any documentation from the New theater version of Apartment, we only had one Skype meeting with Max & Calla while working on our adaptation. Possibly, we are finally going to see some pictures soon.

Max Pitegoff: We didn’t want you to have a preconceived idea of how the play should be performed. The script we gave you was the result of this kind of collective work, which we thought you should continue changing through your collective work.

Calla Henkel: The version of the script we wrote before we started rehearsing was totally different than the final version, which had changed so much during the performances. We realized we needed to transcribe the live version that we had filmed.

Sasa Lubinska: At the beginning I couldn’t get why my character is laughing and then crying…

Dominika Ciemięga: At first we had problems with understanding our characters, and we wanted to adapt it in order to make it comfortable for us.

Max Pitegoff: We were also impressed that you guys have no director…

Calla Henkel: Back then we also tried to work with no director, but we learned quickly that we actually need someone in that position so that everyone can keep sane, so we are very impressed about what you guys pulled off without that. How did you work without a director?

Monika Dembinska: I think it is interesting that it would all come together accordingly to the way the text is constructed. Everyone was adding something. That’s why, it’s more or less made by chaotic fragments.

Dominika Ciemięga: Each of us had a say and could equally contribute.

Monika Dembinska: And it fits well with this text.

Dominika Ciemięga: The most difficult part in my opinion was the choreography. Sometimes we would bump into each other.

Dawid Furkot: There was no identical version, each time we did things differently.

Dom Mody Limanka, Apartment (original script by Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff). Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Calla Henkel: Was there a rule that you guys had? How you keep something and how do you let something go? Max and I set up rules with the structure, so that we could have no rules on stage, but you have to build a world that allows you to do that.

Max Pitegoff: Yeah, the actors we were working with would veto something, and we couldn’t say no to them.

Kacper Szalecki: We honestly had no idea that the project would grow so much. Into this hybrid dimension…

Sasa Lubińska: It was supposed to be just a performative reading.

Agnieszka Pindera: But I hope you don’t regret this choice, and how it all developed well.

Kacper Szalecki: No, we had a wonderful, fruitful and creative time.

Dominika Ciemięga: If you guys want to see another, completely different version, please join us tomorrow [laugh] and the first real rehearsal we had was only yesterday [laugh]

Dom Mody Limanka, Apartment (original script by Calla Henkel and Max Pitegoff). Photo by Anna Zagrodzka

Monika Dembinska: We were reading in smaller groups, also because not everyone is based in Łódź. We had only few rehearsals with the complete cast.

Kacper Szalecki: This leads to another issue. The performance is set within the exhibition space, quite a peculiar environment, with all those insured artworks around us. We had to prepare the scenography in advance, but we could only set it up in the last moment.

Monika Dembinska: Rehearsals were taking place when the exhibition was already open for public. It is quite a hectic space, with all the video and sound works going on, and the audience.

Sasa Lubińska: I am so impressed that the museum allowed us to built this thing [pointing at the coffee maker] and actually use it, and pour hot water in it!

Monika Dembinska: Right, before we weren’t even allowed to bring water into the exhibition space. [laugh]