Painting Meaning

or How to Look at a Painting.

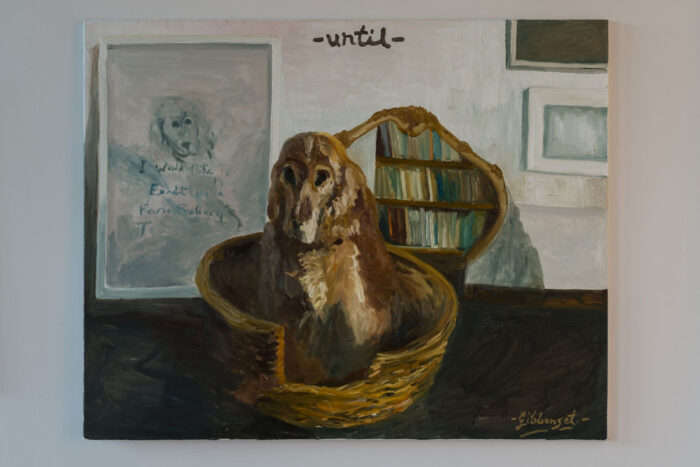

Jeff Gibbons’ paintings are like a form of visual syntax with a linguistic twist. He includes phrases culled from lyrics, art terms and sayings. Although conceptually driven they are very accessible, and funny. The handling of paint shows an engagement with paint’s material qualities and dichotomies between figuration and abstraction. His use of paint incorporates subtle, at times blatant word play, underscored by humour. Gibbons combines familiar expressions with everyday objects like cups, glasses, bottles, tables, flowers and birds.

Although conceptually driven they are very accessible, and sometimes funny. The handling of paint shows an engagement with paint’s material qualities and dichotomies between figuration and abstraction. These are paintings to be seen as well as read, like the rebus and its image-word application (a is for apple). His use of paint sometimes directly echoes the subtle, deadpan humour of the expressions. Literary rather than literally by association, the titles describe a way of working and thinking through painting. The following are two different literary responses to his exhibition NowHere Factual Nonsense, curated by Jo Melvin: the first is Joanne Laws’ Indexical Variation – A Concise but Expandable Compendium To Encountering the Artworks of Jeff Gibbons, and Dialogue of two Moons in Exile: a response to Jeff Gibbons’ painting “Moon” by Gertrude Gibbons.

I n d e x i c a l V a r i a t i o n

“Art Comes Out of Art”[i]

Baldessari will be remembered as a pioneering prankster and a conceptual interrogator of language. Image and text, picture and script, diagram and instruction, icon and mantra. Art was created for the eye and hinted at through words. A form of self-referential commentary, John Baldessari’s art had the inbuilt capacity to cast public scorn upon itself.

Concrete Poetry, as a linguistic device, titillates the written word. Typographical arrangements (with freefalling letters) conspire to enhance meaning.

Dialogue of Two Moons in Exile. There is a ghostly resemblance to “Eve’s grieving upturned face.”[ii] We envision the uncontained moon as silver-gilded lake – as the shimmering embodiment of poetry.

Expanded Painting reflects transient states of being. Some say it concerns a “post-aesthetic discourse”, attuned to an uncanny tension between the presence and absence of painting. Interpretation, we learn, may be possible in the gaps between these planes of exposure. Hoisting works above the viewing plane transforms the gallery itself into an “exploded painting”.[iii] All works are brought into relation, making us aware of our own verticality—of painting as a spatial encounter.

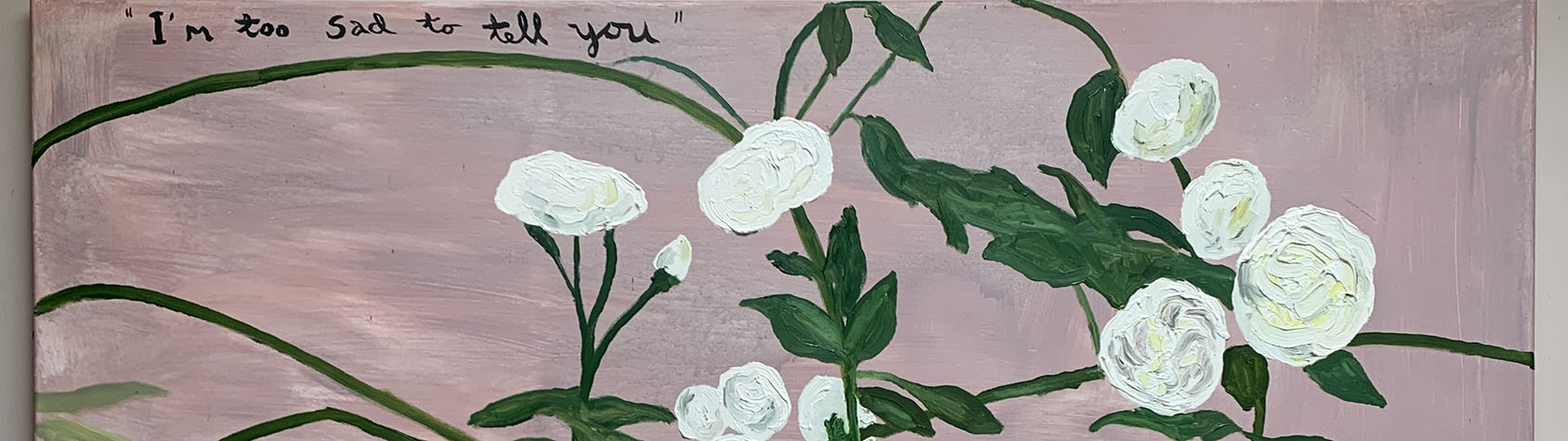

Flowers blossom everywhere, as universal signifiers of beauty. Fleshy fists of paint merge with impasto whirlpools, in hues that are saccharin sweet. Mallarmé grappled with the possibility of portraying an idealised or pure flower: “I say: a flower! And, out of the oblivion into which my voice consigns any real shape, as something other than petals known to man, there rises, harmoniously and gently, the ideal flower itself, the one that is absent from all earthly bouquets”[iv].

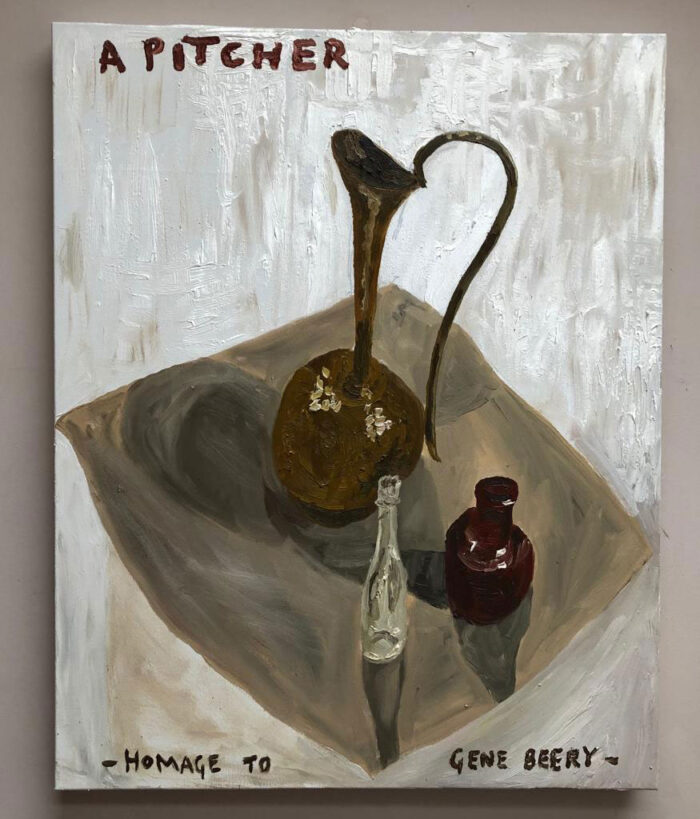

Gene Beery was a conceptual painter also drawn to language. A satirical “Pitcher” (painted in homage to Gene Beery) interrogates the moment of aesthetic encounter.

History – Being so cheerful keeps me going (2005). An effervescent rebuff, a hopeful antidote to personal surliness and a grim collective history of war, death and imperialism. A similarly melancholic disposition extends to other paintings, like Seven Last Words, featuring the nihilist phrase: “There is no point in being here.”

In Search of the Miraculous (1975) / Homage to Bas Jan Ader (2019). A tender raft of white roses floats upon a dusky pink void. On 9 July 1975, Ader sailed out of Cape Cod harbor in pursuit of The Netherlands, concrete truth and the elimination of artifice. His vessel, Ocean Wave—the smallest boat ever to cross the Atlantic—was recovered 10 months later, but his body was never found.

Judgement (2019)—The artist enters wearing a judge’s wig. He traverses the perimeter of the former courtroom holding a burning wick, before lighting the central candelabra. A comically hyperbolic Dickensian character, he channels Victorian morality, his performative gesture, a visionary act, serving to illuminate the darkness.

Knowledge of art historical practices informs the subtle recycling of images and words through humour. A large-scale canvas devoted to books attests to the source of references and the discovery of meaning. In many ways, he plots his own endeavors as a painter against the language and history of painting. “Homage”—featuring prominently within titles and upon canvases—gestures towards an often out-of-reach history of visual culture.

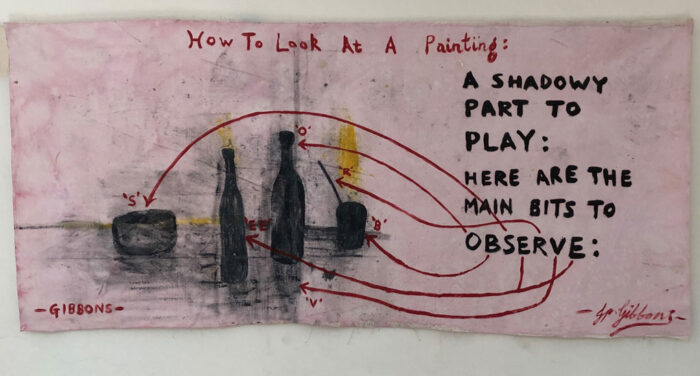

Looking at a Painting—“A shadowy part to play: Here are the main bits to observe.” A dysfunctional diagram to mock the over-theorization of spectatorship in art, which historically denies painting the autonomy to speak freely to its viewers.

Moon (2004). When astronauts first landed on the moon, rather than a luminous white entity, they encountered a dark, rugged terrain, the color of fresh, grey concrete. The fact is the moon is only ever illuminated on the side facing the sun. The other half remains in constant darkness, unseen from earth. Orbiting us, controlling our oceans, the moon—in a perpetual state of partial disclosure—has been known to us throughout human history, yet it never fully reveals itself. There is something rather melancholic about that.

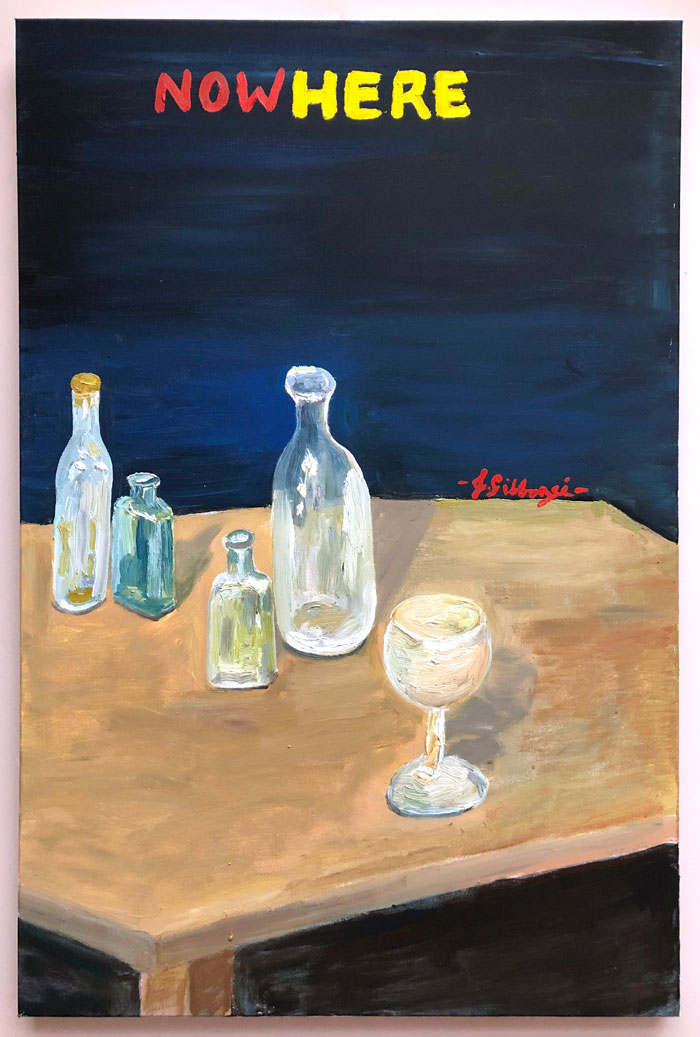

NOWHERE (2018)—Now Here / Nowhere. The artist acknowledges the opacity of history and the slipperiness of time. This Quantum-like proposition anchors our one and-only body. It gives us the tools to organize reality in the present moment, as we see and experience it. We find that the past, like the future, exists as a spectrum of possibilities.

Objecthood is central to art historical debates in aesthetics. Michael Fried’s famous critique of emerging art practices in the 1960s centered on artworks that were indistinguishable from everyday objects and materials, thus deviating from the normal conditions of art. These works, according to Fried, required the presence, intellectual engagement and theatricality of an audience, in order to be considered art objects.

Past painting. Still Alive. All painting is modified by the past to exist in the present.

Quotidian objects masquerading as sacred artifacts. Crockery, bottles and flowers recall Dutch interior painting and art historical tropes, later subsumed by modern advertising. Manet’s nineteenth-century claim reverberates: that still-life endures as the “touchstone of all painting.”

Roses bloom all around. There is a Dawn Rose and Night Roses, Seven Manly Roses and one Homogenous English Rose, collectively channelling a sense of enduring romanticism.

Salon-style hang refers to a seventeenth-century system for the floor-to-ceiling display of paintings. The format was criticized, rejected and gradually dispersed (due to associations with the elite and conservative academy), only to be revived as an embodied form of contemporary critique.

The artist’s signature—painted in a swirling, cursive fashion—dominates much of the canvas. Occasionally it even takes the form of an anagram. Artist signatures have galvanized the art market since the early Renaissance (attesting to provenance, authorship and value) yet they are swiftly becoming outmoded. Henceforth, new digital systems like Blockchain will track physical works through cryptographic links, based on verifiable data.

Umbrian Umbrella (2017) conflates notions of pageantry and pilgrimage. Along the ancient Roman trade route, the umbrella doubles as a mobile art gallery, with paintings pinned to its interior. He wears a straw boater hat, associated with Venetian merchant sailors and still worn in a performative capacity, at political conventions, rowing events or barber shop quartets.

Visual syntax is achieved through word-image arrangements. Clichéd images are accompanied by familiar phrases, creating a pithy commentary on the language between objects. A floral painting, emblazoned with the epigram ‘Abstract Expressionism’, is just one example of ironic signposting.

Wordplay is underscored by humour at every turn. Many titles describe a way of thinking through painting, using word association and visual puns. Oxymoronic statements, like “Factual Nonsense”, hold seemingly contradictory positions together in creative confluence.

Young dove (2017) recalls the iconography of religious painting. Traditionally portraying the Holy Spirit, doves appeared frequently, most famously in The Coronation of the Virgin (1645), painted by Velázquez as an altarpiece for the Alcazar in Madrid.

i. Timothy Emlyn Jones, ‘Art Comes Out of Art: A Conversation with John Baldessari’, The Visual Artists’ News Sheet, July/Aug 2006.

ii. Gertrude Gibbons ‘Dialogue of Two Moons in Exile: A Response to Jeff Gibbons’ painting Moon’.

iii. Jo Melvin in conversation with Gertrude Gibbons and Joe Walker, The Dock, Carrick-on-Shannon, 4 January2020.

iv. Stéphane Mallarmé, preface to René Ghil’s Traité du Verbe (Paris: Giraud,1886).

Dialogue of two Moons in Exile

In Masaccio’s Garden of Eden (1425), there is shame, nakedness, a raw realisation of vulnerability. Adam covers his face with both hands, leaving his genitalia free; Eve covers her body but leaves her upturned face exposed. It is as though, for Adam, the pain of the nakedness is the more shameful part of awakened knowledge. Crying into his hands, Adam looks inwards, while Eve lifts her face to the sky, crying outwards, revealing her suffering for observers to judge. The painting depicts two scenes from Genesis simultaneously, both the moment of their awakening within the garden and their departure from it: “God sent him forth from the garden of Eden, to till the ground from whence he was taken”. Moving from left to right, the two figures have walked out of the gates; yet since God clothes them before their departure, their depicted nakedness sets them at an instant while they are still in the garden. It is as though cloth cannot hide their grief; their naked pain goes beyond and through their temporary clothing. Sent to work “the ground from whence he was taken”, their walk through the gate gestures towards a cycle: their departure is also a return, their hands will create with the earth which created them, and realisation of coming death is also knowledge of their birth and origin.

In Jeff Gibbons’ moon painting, there is a ghostly resemblance to Eve’s grieving upturned face. The moon, traditionally female (ancient Roman goddess Luna, Selene in Greek mythology), bares the same face of exposed grief. As Eve looks to the sky, the moon looks to the earth. The resemblance creates an exchange, a silent mirroring of pain, between the expelled woman looking up, and distanced moon looking down. In the vague, shadow-like smudges of the paint, it plays with a sense of hazy recognition: there is a familiarity of the face, a face indeed imitating the moon, but one that consequently denies seeing anything other than a face. The moon itself, depending on how someone is taught to look, is thought to resemble various other things including a frog, rabbit, dragon. Here, the blurred stokes assert themselves as a face, and one which recalls Masaccio’s Eve. As such, the painting’s dialogue is between an image of Eve and an image of the moon, provoking a consideration of the moon’s possible connection with Eve, with expulsion. The moon, supposedly born from Earth (Giant-impact hypothesis), and expelled into the sky, has its face exposed by night, by light reflected from Earth. Perhaps, like Eve, Gibbons’ moon desires cloaking; the painting desires cloaking in darkness, but this offers no escape since it is night’s darkness which exposes her face. She cries at the world which looks at her, casts a light on her; she cries at her nakedness. The brightest object in a night sky, she is alone, and depicted alone on the canvas’ inky background. Paint, like night, paradoxically works here both to cloak and reveal, just as Adam and Eve’s clothes: their clothes hide their nakedness on the one hand, but reveal the painful consciousness of their nakedness on the other.

Recalling its origins from mud, earth, paint draws the face from the blank space of canvas. Soil working across cloth. As mankind in Genesis is sent to “work the earth”, painting works the earth. Painting as earth lives trapped in this liminal world between origin and return, between the mind which creates the image and another which receives it. If the Garden is like the pure realms of the imagination, the shadows of thought before expression has given them substance, then the act of painting mimics the expulsion: once expelled from the mind, the painted shadows live and work the earth as prisoners, waiting for the return. Both faces, Eve and the moon, while they look outwards, are surrounded by an impenetrable silence, a blindness which forbids them to see outwards. They are imprisoned, even as they desperately bare their faces to the world.

In a 2018 performance by Gibbons, accompanying his exhibition at the Tempietto sul Clitunno, Italy there was an emphasised sense of the cycle, the return to earth, and exchange between ground and sky. A bird, painted upon canvas, sits above twigs which have been glued to the cloth. On other canvases there are flowers. In the performance procession reminiscent of a pagan or early Christian festival, each attending person was handed a flower. In this way, there is a certain ‘rhyme’, an echo, between the people and the work, the materials and the painting. The flowers have walked out of the paintings, as the twigs emerge from the canvas, with the suggestion that the paint left behind is a shadow of the three-dimensional object. It is as though, in the hands of the spectator, the flowers have been freed from the canvas; the viewer has given life to its two-dimensional rendition. Once again, it points towards the nature of paint as earth, and it is from soil that flowers spring. The painting itself comes from a certain ‘idea’ of a flower, an expression of a thought. This might recall Stéphane Mallarmé’s famous writings, “Je dis : une fleur ! et, hors de l’oubli où ma voix relègue aucun contour, en tant que quelque chose d’autre que les calices sus, musicalement se lève, idée même et suave, l’absente de tous bouquets”. As soon as the flower is named, it mysteriously appears from the indistinguishable shadows of the mind. Yet this flower, having risen, having been named, is also revealed as absent: it moves from absence to absence, from one nakedness to another. Likewise, the flowers spring, grow, from the shadowy contours of the artist’s mind onto the canvas; but, like the word, they only gesture towards flowers, exposing the real flower’s absence. But this absence was temporarily denied in the performance, through the giving out of real flowers.

Originally displayed in the form of a book, (Concrete Absolute, 2004-5) the black and yellow of the canvas Moon draws a parallel with written word on paper, and the empty naked space behind and around the lines of text. The dark strokes reveal a hand which interrupts the brush’s movement, blurring the lines, seeking to fuse them with the cloth, hold them there. They assert the process of their creation, the source of their materials, the roughness of canvas, the grittiness of earth. As Adam and Eve are clothed and sent to work the earth from which they came, so the page is painted in a gesture towards the mud from which paint came, and the nakedness behind it. Painting, nailed to the wall, is subject to the gaze of others. Here, in Moon, it is naked and humiliated, awaiting judgement. The prisoner awaits freedom; a freedom only the viewer is empowered to give.