Out of the Foxhole

Toward a Precarious Art History

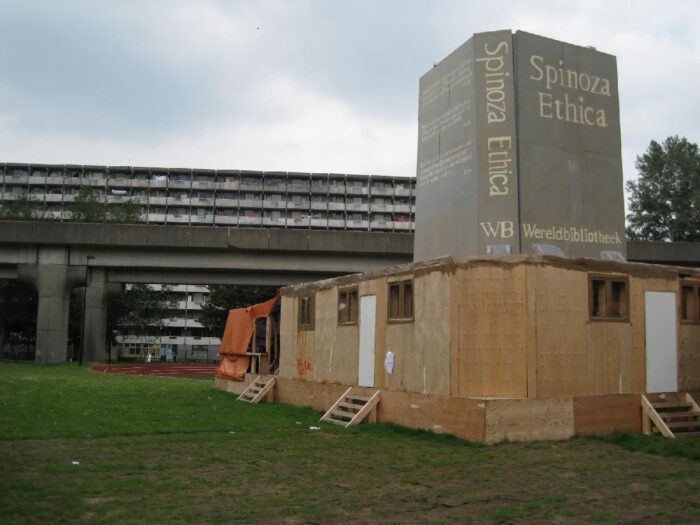

The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival is an artwork, a sculpture, created by Swiss artist Thomas Hirschhorn in a peripheral borough of Amsterdam’s south-east known as the Bijlmer in 2009. The book The Ambassador’s Diary recounts the event through the eyes of its “Ambassador”, art historian Vittoria Martini, who was invited by the artist to be an eyewitness to the existence of this “precarious” work.

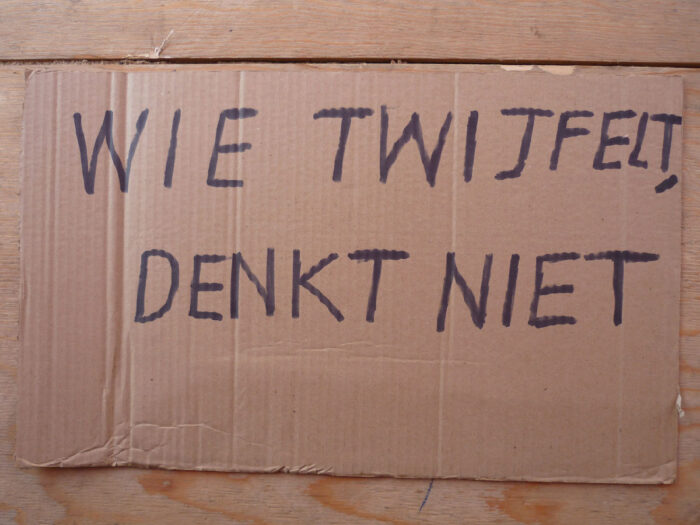

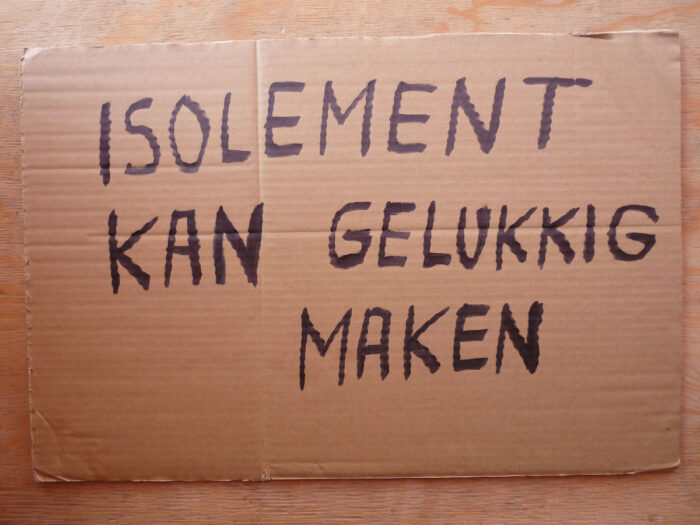

Between May 2 and June 28, 2009, Thomas Hirschorn opened the Bijlmer-Spinoza Festival to the public. It was a vast architectural sculpture, a space in which to host events celebrating Baruch Spinoza and his major work, the Ethics. Not affiliated with any institution, the monument was installed in Bijlmer, a failed utopian working-class neighborhood southeast of Amsterdam. In retrospect, the Festival also appears as a failed utopia, although the artist rejects this approach to his work. The daily performances and events were often without an audience, and the hoped-for discussion never seems to have been sparked. Anyway, for Hirschhorn, the highest significance of the Festival’s obscure philosophical readings and theatrical performances lay in the very fact that they happened, that someone was steadfastly committed to making them happen, not that they were understood, crowded, or had a concrete impact.

Italian art historian Vittoria Martini, a Ph.D. student at the time, was there for the whole duration of the Festival as the Art History Ambassador. Her role was just as obscure as the meaning of the daily events, her commitment just as decisive. Almost fifteen years later, Vittoria decided to publish her diary of those days. In addition to offering a treasured account of the Bijlmer-Spinoza Festival, her journal proposes an original method of contemporary art history and art writing, openly addressing questions haunting anyone who engages in the history of contemporary events.

Stimulated by the constant discussion with Thomas Hirschhorn, a living, ever-present, extremely demanding, and unabashed artist, Martini challenged the notions on which she had learned to base her historical practice, rediscovering the value of subjectivity and the non-historical. Moments of crisis and exaltation—the most powerful and most revealing passages in her diary—fueled this process:

“I only have the energy and time to cook pasta, and I have not yet understood why it is always me who has to cook. This has to change. (page 45; spoiler: it didn’t change, see page 130)

I cried yesterday evening, in the kitchen, because at some point I didn’t give a fuck about Rembrandt, what the fuck do I care about defending Rembrandt at 11pm after yet another improvised dinner in this absurd place, and after yet another exhausting day? […] I have been torn to pieces. I’ll get over it. Fuck. I just need some sleep. (131)

I am exhausted, full of beer, and my lungs are heavy with menthol cigarettes. (162)

What makes me happy is that, without control, out of urgency and precipitation, completely overwhelmed in doing something impossible, we achieved within every performance, some very short, rare, and furtive moments which had beauty, precariousness, and grace. For these very few and exceptional moments it was worth going through such a disastrous experience. (170)”

Vittoria’s first challenge was to define her role and determine if she was the right person for the job. Being an ambassador means representing and embodying the values, laws, and principles of a nation (or discipline) beyond its borders. As the art history ambassador, she had to carry the burden of historiographical approaches and methodologies into an event that was still evolving. To represent them. And to defend them.

“Very complicated: I am the Ambassador of art history, but I can’t use the criteria and lexicon of art history. Art here becomes a metaphor for everyday life, reduced to its primary essence, the absolute simplicity of making as a need inherent in the human being. (57)

I am the eye of the Spinoza-Festival; I am not visible, but it is me who tells the story and I do not want to be visible, perhaps because I still believe that the Ambassador should have as little influence as possible on the idea that you get from the images that will remain of it. (70)

To be the Ambassador at The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival means to be here, to be present, and it means to produce: namely, to make the effort to start thinking now […] To be the Ambassador at The Bijlmer Spinoza-Festival is to try to make history in the here and now. (125)”

Hirschhorn had a fairly definite idea of what this “history in the here and now” should be about. Toward the end of the Festival and Vittoria’s journal, he offered her a clear definition:

“So, your role, now, is to watch and to witness. You are not invested in the project professionally, beyond the fact that you have given up two months of your life to be held captive in Bijlmer (reality television comes to mind). You can collect materials for the future—such as the videos I saw you making—but remember that this is already a project with a surfeit of information. You can archive, but for me the most poignant activity you could do is to use your specific competences (language, analysis) to distill and reduce the experience you are participating in. Create concision from the informational excess and overload of experiences around you. Find a new methodology for analyzing this kind of work from the inside. (173)”

That had been Vittoria’s approach to her mission over the previous weeks. In addition to taking photographs, recording videos, and working on the daily Festival newspaper, she had begun challenging her specific competencies to adapt her historical methodologies to the Festival’s peculiar context. This approach resulted in the choice of writing a diary, an original proposal of art history, based on a subjective and inherently precarious perspective: a kind of extreme compression of Lucy Lippard’s Six Years; or Carla Lonzi’s Autoritratto, focusing on just one single work of art. There is no point in paraphrasing the meaning of Vittoria’s activity when she defined it so well, surfacing the personal value and emotional resonances of journaling:

“I realize I have started to keep a diary to remember what happens, who I meet, what I think, to daily note down my feelings about this place, where every day is an epoch. Everything happens too quickly. When I was a young girl, I always kept a diary and I remember my pleasure in picking it up again after months to reread what I had felt in certain moments. It was therapeutic, it was good to see things in perspective, not to forget about them—it helped me grow up […] I think that the diary is the only possible form of production during this forced presence. Pure chronicle, as in a foxhole, where there is no time to think long and deep, but only to take quick notes that preserve the feelings you experience in the moments that follow each other, the exceptionality of minimal, usually invisible moments. There is no time to think, to develop, to produce thoughts in this constant state of emergency, of exposure to events and people. The diary becomes the only possible form of production at the very moment in which a work like this takes shape. (50-52)”

As her journal and time at the Festival progress, Vittoria develops a new approach to contemporary art history. Dealing with the present prompts her to question the concepts of history, art history, contemporaneity, and history-making. The here and now does not allow certainty: objectivity is impossible, and the only possibility is precariousness. Her proposal for a precarious art history thus takes shape through everyday life moments of crisis and uncertainty. What makes it unassailable is not firm theoretical principles but her direct experience.

“I am thinking about the time of history, about the importance of presence and experience for the production of history. History begins when experience ends. I have a problem with being neutral and critical because I am totally immersed in the experience. The issue of intellectual property. He talks about reappropriation. The issue of the stage/platform. You are here, you could be anywhere. (60)

To think about the meaning of ‘history of contemporary art’ is to realize that it is an oxymoron. How to write history about facts that are happening? (124)

He asked why I never wrote ‘I believe that’ or ‘I think that.’ He nailed it: Why didn’t I do it? Did I get too far into interpreting this universality of my role as an Ambassador, this idea I formed that it is not important that it is me, that I could have been any other art historian? I practically gave myself up, but I had not seen that if Thomas asked me it is because he wanted me, specifically. I keep asking myself why. I keep feeling inadequate for this role; I feel I have a huge responsibility and I think I am unable to live up to it. (126)

Is history made only after experience has cooled down? Or is direct experience impossible if your goal is to write history? But how can you write history objectively without the knowledge resulting from direct experience? It involves deep work, which you can only do by putting some temporal distance between you and the experience; it involves the development of a critical insight that comes from detachment, as after a traumatic experience, which you first reject, then overcome, then process. It takes time. (135)”

Alongside this long series of personal experiences, the diary also records a process of intellectual elaboration by chronicling a sequence of encounters with inspiring texts and people. Books and papers cited include T.J. Clark’s intimate, diaristic approach to two Poussin paintings, The Sight of Death. An Experiment in Art Writing (2008), Elsa Morante’s harrowing account of the years of Fascism and World War II in Rome, La Storia (1974), Theodor W. Adorno’s renowned rejection of political art, Commitment (1962), and Rosalind Krauss’s seminal essay, Sculpture in the Expanded Field (1979). These texts proposed innovative historiographical approaches in light of dramatic events or particularly challenging works of art. In the final lines of her essay, Krauss openly acknowledged that her approach “presupposes the acceptance of definitive ruptures.” In Bijlmer, where social contacts were inevitably limited, words like these were comforting presences. Together with books, some people played a vital role. In the finale of Vittoria’s diary—as in some political plays of the 1970s—the Festival is visited by an impressive crowd that stimulates Vittoria’s reflection on her approach and role. Lisa Lee, Mignon Nixon, Claire Bishop, Hal Foster, Georges Didi-Huberman, and Toni Negri take the stage. The accounts of these meetings and the transcript of the emails that followed them tell the story of a passionate pursuit of external interlocutors. The encounters encapsulate the psychological and intellectual condition of many young researchers finally finding a method and new reference points. At times, they also offer a beneficial counterpoint to the Festival’s ideology, giving voice to the reader’s perplexities and feelings:

“Claire Bishop came the other day, and the first thing she asked me, in an ironic tone, is if I am a ‘fan’ of Hirschhorn. Her overconfident tone made me really upset. We talked about this; she knows the work of Thomas by heart, and it’s clear that her provocative question was not addressed to me personally, but to me as the Ambassador: a highly sophisticated insider critique. Claire is among the art historians I admire most, precisely on account of her sharpness and brightness—she always finds unique points of view on things that seem to be taken for granted. Claire is brave, and good at arguing. She started following Thomas while he was preparing the stage setting, and never stopped asking him questions. Thomas smiled as he answered because she doesn’t give in until she gets what she wants. (161)”

All these texts, encounters, and experiences come together in the diary. After remaining private for fifteen years, it came out as a book. What is most striking about it is the topicality of Vittoria’s writing and her way of approaching and deconstructing history. In contrast, the Festival appears to belong to a very remote era. Maybe this is due to simple generational distance: back in 2009, I was thirteen and had no idea what contemporary art was. Or it may not be just that. It would be too difficult to recall everything that has happened in the last fifteen years in the art world that has made certain participatory art age so quickly, but it is evident that we are now witnessing an overall historiographical reworking and questioning of the art of the early 2000s. The first example that comes to mind is Claire Bishop’s recent contribution to Artforum: Information Overload. Vittoria’s proposal of a precarious art history timely fits into this discussion. A redefinition of a certain kind of art also imposes a redefinition of a certain kind of art history. The disheartened collapse of great ambitions and expectations forces us to rephrase our memories in a minor key. Our certainties proved fragile, and embracing precariousness is the only way to historicize them. The anti-historicist approach has a long tradition that goes back, in some ways, to the birth of history itself. In art history, it has taken longer to take hold. Committed to asserting and convincing scholars from other fields of the value and historicity of their young discipline, art historians have made historical objectivity the cornerstone of their methodology, especially in Italy. Around 1968, contemporary art historians modeled their new discipline on the art history of earlier centuries. To earn their way into university classrooms, they had to study Arte Povera with the same tools applied to the Renaissance. The few opposing voices were all outside the academy or were being pushed out of it. The ghost of objectivity imposed an insurmountable separation between art history and criticism, between art historians and critics. Vittoria’s proposal may help mend this rift in the name of precariousness. What is needed is not a stronger criticism, but a more precarious art history.

“The feeling is getting stronger and stronger that the place I’m in will no longer exist in the future, and that this conversation, too, will never take place again. This is what makes all of this precious: the precarity of it, and the consequent awareness that the moment we are living in is unique. And it seems we are all struggling against this, trying to leave our mark somehow. We cannot do the task of art history, but we can do the task of art. (132)”

The Italian language does not differentiate between ‘story’ and ‘history’: it has a single word, “storia”. Several generations of Italian readers and art historians have read Ernst Gombrich’s The Story of Art, convinced that the original title was The History of Art. To avoid this misunderstanding, Italian translators applied two different strategies. In 1952, Mondadori titled the book Il mondo dell’arte, literally “The World of Art”. It was not a good translation. In 1966, Einaudi opted for La storia dell’arte raccontata da E.H. Gombrich: the verb “raccontare” (to tell) transformed the author into a subjective narrator, the history in a story. I am not sure if it worked. In 1974, Einaudi, the same publishing house, published La Storia by Elsa Morante. Now, the problem reversed: the author deliberately played with the ambiguous term, with its being valid for both story and history. English translators had to choose sides, resolving the ambiguity one way or the other. In 1977, William Weaver came up with the ingenious title History: A Novel. A fitting title for Vittoria’s journal might have been Art History: A Diary.