Opium’s Tales

A located cosmo-political imagination of our current ecological era

In The Forest, Even The Air Breathes emerges from the ongoing research of the Forest Curriculum. The Forest Curriculum addresses the need for a located cosmo-political imagination of our current ecological era, rejecting the planetarity of the Anthropocene project, and instead proposing to think with the cosmological systems of Zomia: the forested belt running from the northeast of India, through the Chittagong Hill Tracts of Bangladesh, the Shan state, the Isan heartland in Thailand, the tropical forests of the Malay Peninsula and into the Cordilleras of the Philippines.

It proposes Zomia as the terrain from which to query the Anthropocene: a project, as the post-human critics of the project have pointed out, which assumes the universality of a Western model of the “human” which, in practice has been used by imperialists and state actors to exploit and impoverish those outside (or from within a different framework, in a subaltern position to) its definition. It seeks to imagine what forms of imagination must be invented to think alongside, and become intimate with the many beings of the many worlds we inhabit. The exhibition includes works by Khvay Samnang (Phnom Penh), Soe Yu Nwe (Yangon), Sung Tieu (Hanoi/Berlino/Londra), Karl Castro (Manila), Robert Zhao Renhui (Singapore), Joydeb Roaja (Chittagong), Nguyen Trinh Thi (Hanoi).

In conversation with the works, five publications by artists and researchers (Christian Tablazon, Pujita Guha, Huiying Ng, Wong Bing Hao, and Chairat Polmuk) present modes of engaging with Zomia as a field of knowledge produced in collaboration with RAR Editions. The following is an excerpt from Pujita Guha’s In The Mountains, The Only Money Is Opium.

If , for any reason the opium eater went to heaven, it was because he knew how the chariots worked. Not because the gods wanted him up there.

Opium trade is the logistical imaginary.

—Burmese folktale “the opium eater who went to the heavens”

Opium (papaver somniferum) is that perfect Zomian* cash crop. Because opium thrives in a relatively cool climate, it is usually grown in mountain valleys or on the slopes that are more than 3,000 feet above sea level. It gets by with loose alkaline soil, and being grown on limestone bedrock. In its final form, it is a low bulk commodity, can be freely circulated manifold times , accruing value in the chain. Mule caravans transporting opium along the mountain trails are images that we all know about . Nothing excites one more than the visibilization of risk, that is, not really a risk for those reading about it. As a potent, value accruing object, the opium narrative in Zomia has been one of extraction and expansion, integration and exit. At a time when the British East India company had monopolized opium production and circulation globally (roughly 1820s to 1920s), through war or through politics, or as the old adage goes ‘politics is war by other means’, for china, growing opium locally, especially in its Zomian southwestern regions, became means to restrict the outward flow of capital, whilst satiating an increasingly addicted population. For the Zomian population, opium became means by which integration were to happen to nation states, but written to the tune of extraction, dissipated modes of violence, and a perpetual state of war.

To think of cash crops, plantation and extraction economies, is to have a flat imaginary. Either you dig deep, in neatly sedimented layers, or you inscribe grids and contours across alluvial plains. Agricultural economies pan out in fertile, verdant, often flat, expansive landscapes that stretch for miles approaching the infiniteness of the horizon. Flatness then is the production of a smooth extractive operation that could be easily scaled up to a model whereby immense capital can be accumulated. If flatness enables logistics, or the smooth transit of materials, goods and technical objects, the question then, is to ask how do forests, hills, zones of refuge for stateless subjects venture into extractive economies? What are the pressures of the informal economy (grey market) and the private militias? How does one then talk about extraction in the mountains and the hills in the Zomian* forests where such flatness is geologically, environmentally and culturally not possible?

The narrative that gets reproduced every single time is the timeless-ness myth of the Zomian highlander who is forever destined to pick up the opium sap on the treacherous mountains. Colonizers could write their own histories that they gifted opium to the massif, (cue the Cesar Frederick J. Horton Ryley story, )but others recollect how opium cultivation was not a traditional activity amongst the hill’s indigenous groups even about half a century ago. Many of the hill tribes of the region (Karen, Lawa, Khamu, Htin) attest to the same, “and tribes that drifted south into the area after the second world war (Hmong, Mien, Lahu, Lisu, Akha) learnt to cultivate poppy in china’s Yunnan province, where the drug was grown from the mid-nineteenth century to offset dependence on British imports.”—Source Brett Nielson, “free trade in the Bermuda triangle” 2004)

*to ask what is Zomian is to foreclose its meaning. Could an adjectival cognate ever relay the historical density of Zomia? Also, to ascertain an adjective is to compute an essence. Could anything fundamentally resist computation?

Capture

Verb: to be taken in by force

Noun: the action of taking in something by force

Also since mid-twentieth century capture refers to the act of photographic inscription on a light sensitive medium.

Opium became a major mode of capturing indigenous communities throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Captured , not as lulled into addiction, but as means by which floating communities from the hills could settle and stabilize within the nation state. For the Hmongs, as they moved southwards and settled in the hills of Laos, growing opium became the way through which they could sustain the price of settlement itself. Opium could be traded for whatever could be afforded in the hills. Food, clothing, shelter , whatever. Or in exchange, performing the labour for belonging to the state itself i.e. war. The Hmongs were highly sought after by the CIA in their war against the Viet Minh. Who would know the jungle hideouts and hills better than them? And would also comply with the statist imaginary? And exhibit sufficient precarity? I had forgotten this narrative until I saw the video of George Floyd’s death. Amongst its many participants were a Hmong-American policeman reinforcing his belonging to the state, with the murder of a black man. And all of this captured in a mobile phone. Also turned back and read Pierre Boulle’s ears of the jungle.

*to ask what is Zomian is to foreclose its meaning. Could an adjectival cognate ever relay the historical density of Zomia? Also, to ascertain an adjective is to compute an essence. Could anything fundamentally resist computation?

“Opium is the opium of the masses”

T.R.C Thailand Revolutionary Council

Date. June 28, 1987

To: u.s. justice department

Washington d.c., u.s.a.

Subject: important facts for the drugs eradication program to be successful

Sirs:

This letter to the us justice department is to make it clear about our deepest concern in wishing to help eradicate drugs and for all the American people as well as the world to know the truth that for the past (15) years they have been misled to look upon us as the main source of all the drug problems.

1. The refusal of the united states government to accept our “six years drugs eradication plan” presented at the congressional hearing by congressman mr. Lester Wolff after his visit to Thailand in April 1977, was really a great disappointment for us. Even after this disappointment, we continued writing letters to president carter and president Reagan forwarding our sincere wish to help and participate in eradicating drugs. We are really surprise and doubtful as to why the US government refuses our participation and help to make a success of the drugs eradication program.

Furthermore, why the world has been misled to accuse me as the main culprit for all the drug trades….. While in reality, we are most sincere and willing to help solve the drug problems in south east Asia. Through our own secret investigation, we found out that some high officials in the us government’s drugs control and enforcement department and with the influence of corrupted persons objected to our active participation in the drugs eradication program of the us government so as to be able to retain their profitable self-interest from the continuation of the drug problems. Thus, the us government and the American people as well as the world have been hoodwinked.

2. During the period (1965–1975) CIA chief in Laos, Theodore Shackley, was in the drug business, having contacts with the opium warlord lord sing han and his followers. Santo trafficante (SP) acted as his buying and transporting agent while Richard Armitage handled the financial section with the banks in Australia. Even after the Vietnam war ended, when Richard Armitage was being posted to the us embassy in Thailand, his dealings in the drug business continued as before. He was then acting as the us government official concerning with the drug problems in southeast Asia. After 1979, Richard Armitage resigned from the US embassy’s.

Posting and set up the “far east trading company” as a front for his continuation in the drug trade and to bribe CIA agents in Laos and around the world. Soon after, Daniel Arnold was made to handle the drug business as well as the transportation of arms sales. Jerry Daniels then took over the drug trade from Richard Armitage. For over 10 years, Armitage supported his men in Laos and Thailand with the profits from his drug trade and most of the cash were deposited with the banks in Australia which was to be used in buying his way for quicker promotions to higher positions.

Within the month of July, 1980, Thailand’s english newspaper “Bangkok Post” included a news report that CIA agents were using Australia as a transit-base for their drug business and the banks in Australia for depositing, transferring the large sum of money involved.

Verifications of the news report can be made by the us justice department with Bangkok Post and in Australia.

Other facts given herewith have been drawn out from out secret reports files so as to present to you of the real facts as to why the drug problem is being prolonged till today.

3. Finally, we sincerely hope in the nearest future to be given the opportunity to actively take part in helping the us government, the Americans and people of the world in eradication and uprooting the drug problems.

I remain,

Yours respectively

Khun Sa

Vice chairman

Thailand revolutionary council (t.r.c.)

“what is the golden triangle if not the perfect schematization of a frenzied, treacherous history?”

“In early 1994, Burma’s army, now re-equipped with Chinese arms, mobilized some 10,000 troops for the first of three massive dry-season offensives against Khun-sa. Since thousands would die in any frontal assault across the deep Salween gorges west of Homong, the Burmese army had to envelop his flanks slowly. Though Khun-sa generally preferred to retreat in the face of pressure, his army, on several occasions, used its formidable firepower to slow the advance—raking Burmese troops with lethal machine-gun fire at a Salween river crossing in January 1994 and inflicting 546 casualties on a unit that attacked one of his border posts in June. Rangoon’s first offensive opened in early 1994 with attacks that forced Khun-sa’s troops out of their zone in the heart of the Shan state, reducing his control to a narrow strip along the Thai-Burma border.” Left –Source Alfred Mccoy, “lord of drug lords” 318-319.

Logistics today maybe referring to protocols at large, but in its definitional expansiveness, people forget its early modern meaning. Logistics for Antoine-Henri Jomini it was “the practical art of moving armies.”

“In the summer of 1967 chan chi-foo (Khun-sa) set out from Burma through the KMT’s territory with 300men and 200 packhorses carrying nine tons of opium, with no int as we were preparing a fire to cook a hot meal our Kachin scout who had just gone down into the valley below to hunt came back up and told us that he had just seen the trampled tracks of at least a hundred loaded-mules on the valley floor. A hundred packed-mules guaranteed that over two hundred armed guards and handlers were there too. We immediately killed the fire and just chewed the strips of boar jerky as our dinner that night. By nightfall we could see the flickering lights of their many firefly-like fires on the jungle-clad valley floor.

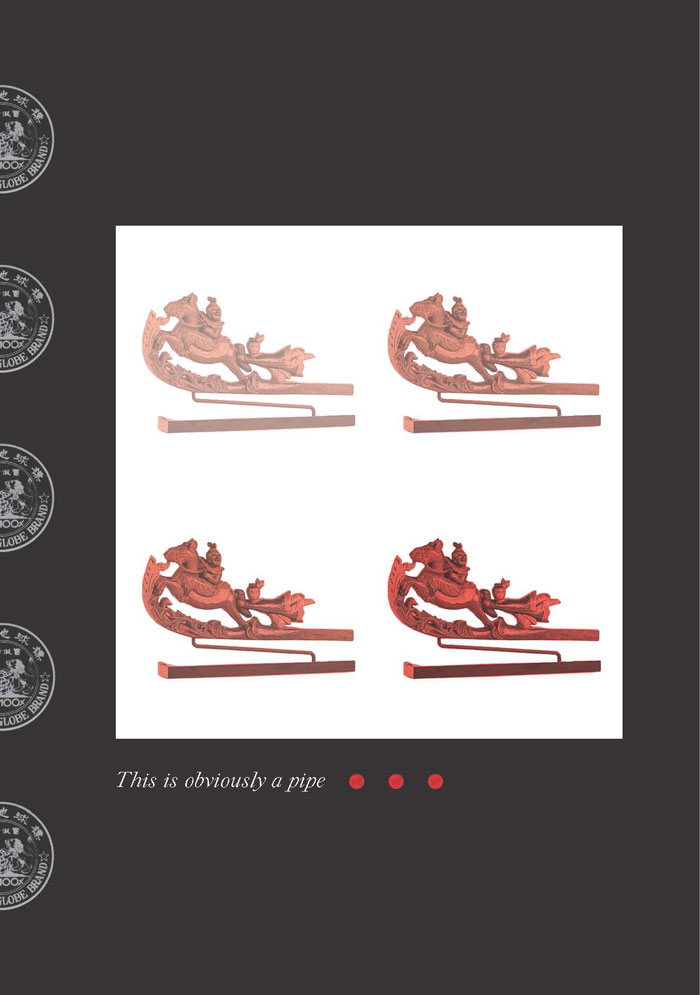

The mule train was one of the regular kia opium caravans heading towards their labs by the border where the raw opium would be processed with lime in boiling water to get the white morphine base. Smokable in a pipe but not yet injectable, the base is then ready for further processing into fluffy-white heroin no. 4.

But the process requires a lot of chemicals like chloroform and acetic reagents smuggled across the border from Thailand, and also a number of expert chemists. So the kia had to mule it farther down south to the more-advanced labs run by the BCP (Burmese communist party)-controlled WA rebels.”—Source Jianxiong Ma And Cunzhao Ma

“The Mule Networks As Cross Border Networks”

But troops cut off the group near the Laotian village of Ban Houei Sai in an ambush that turned into a pitche battle. Neither group, however, had counted on the involvement of the kingpin of the area’s opium trade: the cia backed royal lao government army and air force, under the command of general Oouane Rathikoune. Hearing of the skirmish, the general pulled his armed forces out of the plain of jars in north-easter Laos where they were supposed to be fighting the Pathet Lao guerrillas, and engaged two companies and his entire air force in a battle of exterminating against both sides. The result was nearly 30 KMT and Burmese dead and half-ton windfall of opium for the royal lao government. In a moment of revealing frankness shortly after the battle, general Rathikoune, far from denying the role that opium had played, told several reporters that the opium trade was “not bad for Laos.” The trade provides cash income for the Meo hill tribes, he argue, who would otherwise be penniless and therefore a threat to Laos political instability.

He also argued that the trade gives the Lao elite (which includes government officials) a chance to accumulate capital to ultimately invest in legitimate enterprises, thus building up Laos’ economy. But if these rationalizations seemed weak, far less convincing was the general’s assertion that, since he is in total control of the trade now, when the time comes to put an end to it he will simply put an end to it. It is unlikely that Rathikoune, one of the chief warlords of the opium dynasty, will decide to end the trade soon. Right outside the village of Ban Houei Sai, hidden in the jungle, are several of his refineries—called “cookers”—which manufacture crude morphine (which is refined into heroin at a later transport point) under the supervision of professional pharmacists imported from Bangkok. Rathikoune also has cookers in the nearby villages of Ban Khawan, Phan Phung and Kheung (the latter for opium grown by the Yao tribe). Most of the opium he procures comes from Burma in caravans such as chan chi foo’s; the rest comes from Thailand or from the hill tribespeople (Meo and Yao) in the area near Ban Houei Sai. Rathikuone flies and dope from the Ban Houei sai area to Luang Prabang, the royalist capital, in helicopters given by the united states military aid program.”—Approved for release 2001/08/30: cia-rdp73b00296r00300060028-3.

In Lamberto v. Avellana’s The Evil Within (1970), one organizational network is mapped onto another ,the ad-hoc assembled pan asian transnational film network onto the opium trade in Burma. Kieu Chinh plays princess Koumar Shouria (or really olive yang or so one could assume) a queer drug-war lord in Burma. On the other side of this extremely kitschy b-grade espionage film is a painstakingly constructed documentary by Adrian Cowell The Kings Of Opium. Cowell was the last of the major BBC globe trotting white male documentary filmmakers, spent many years in the jungle hideouts of Khun Sa and his army, recording the everyday logistics of a truly global trade network. Beyond this seeming difference, and the self-imposed seriousness of the lone BBC filmmaker treading the rough tropical forests, are the mule caravans traversing the mountains, carrying opium/partially processed heroin through its thickets. These caravans could sometimes extend for miles, crawling the mountains in a stagnant line. The mule caravans are probably the only form of transportation that could take on mountain gorges and forest trails in a day’s span, and also disperse rather easily in the face of an attack. The mule caravans were the signs of an empire and as the face of the opium trade is logistics inscribed into iconography.