On the Frontline

Creativity and beauty in the midst of collapse

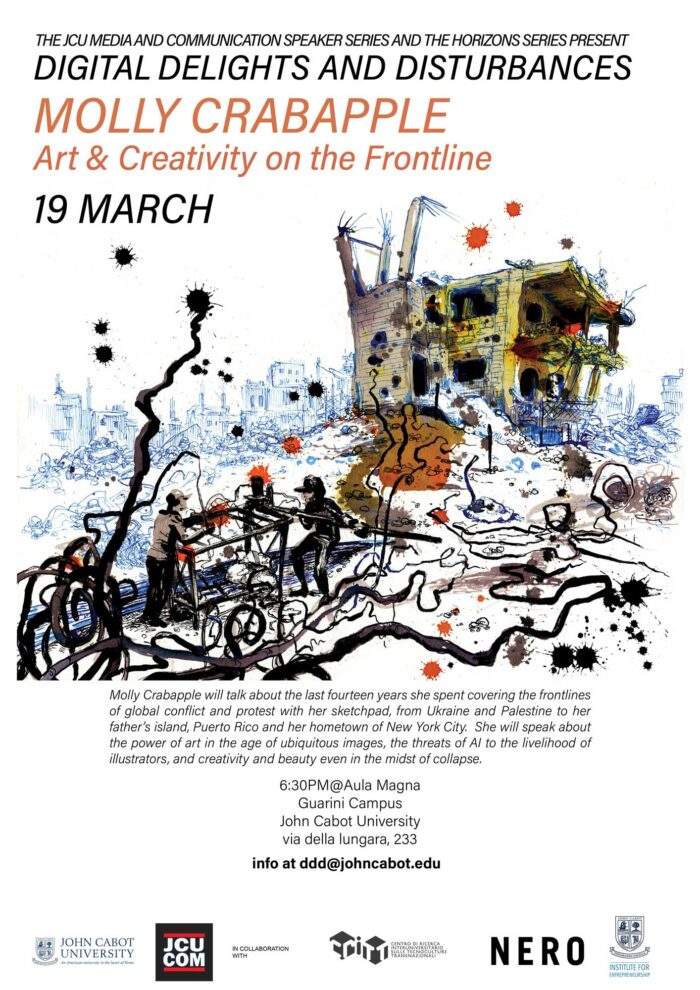

The Department of Communication and Media Studies, and the The Institute for Entrepreneurship at John Cabot University welcome Molly Crabapple, artist and writer, to talk about the last fourteen years she spent covering the frontlines of global conflict and protest with her sketchpad, from Ukraine and Palestine to her father’s island, Puerto Rico and her hometown of New York City. On this occasion, she will speak about the power of art in the age of ubiquitous images, the threats of AI to the livelihood of illustrators, and creativity and beauty even in the midst of collapse.

The talk will take place on March 19th, at 6:30pm, in the Aula Magna Regina (Guarini Campus) John Cabot University, Via della Lungara 233, as part of the Spring 2025 edition of the event series Digital Delights & Disturbances (DDD).

The DDD Event Series is organized and sponsored by the JCU Department of Communication and Media Studies, in collaboration with NERO and CRiTT (Centro Culture Transnazionali).

You can RSPV here. More info at [email protected].

How can we bear witness to our times and resistance movements, or how do you it?

Molly Crabapple: I don’t know what bearing witness means. I live in the world like any other human. But I’m an artist, so I document it with my pen in all its beauty and ludicrousness and horror. Sometimes this means drawing at nightclubs, and sometimes that means drawing in refugee camps, courtrooms or protests. I draw fast, with pen and ink and watercolor in a sketchpad, then sometimes take sneaky iPhone photos in order to do more detailed drawings later.

Since when are you “drawing blood”?

I’ve been drawing since I was four, and got my start doing illustrated journalism during Occupy Wall Street. I was annoyed at the contemptuous and inaccurate treatment that much of the media gave the protesters, and decided to document them myself. I would go down to the encampment with my sketchbook almost every day, and was soon doing posters for the movement. When I got arrested at Occupy’s one-year anniversary, I wrote an article about the experience. This was my first real break as a writer.

What is the relationship between memory and practice, be it writing, drawing or reporting?

I was always obsessed with history—particularly the histories of bad girls and political rebels. And while New York City is obviously several thousand years younger than Rome, the past is all around us. It’s in the memorial murals of longtime residents who have died that are all over my neighborhood. It is in the names of streets, in the palimpsest architecture of buildings, in the lineage of protest chants. I can’t see the present as cut off from the past, and when I document the present, I tend to look for antecedents, whether they are obvious or not.

And how do fascism and oppression work on forgetfulness?

The first thing a fascist movement does, even before it attacks the enemy other, is it seeks to purify the self. It tries to erase the dissident, cosmopolitan, and solidaristic parts of its own people’s history. Look at what the Nazi movement did in Germany, one of the most sophisticated, intellectual, cultured societies of its era. All of this was torn away in favor of torchlight parades, brown shirts, spectacular violence and idiotic mythologies about werewolves. Fascism demands that a society has a simple, stupid story.

Amidst waves of silencing, why is it so important to bear witness and tell the truth?

Why is it important to bear witness and tell the truth? My god—because the worst people on earth are in power in my country and they are deporting immigrants to gulags in El Salvador and locking people in jail for speech. They are destroying the little tiny social safety net we have. They are about to impoverish us all. I like libraries. I like cities where people come from everywhere. I like not breathing in toxic chemicals. I don’t want my friends to be imprisoned or exiled or die of some totally treatable cancer because their health insurance was stripped. I don’t want Elon Musk and his band of incels to erase our history, mutilate our present and destroy our futures. So I raise my voice. It’s the bare minimum.

Can you talk a bit about creative resistance and civil disobedience in the context of the Jewish Voices for Peace movement? Can you also elaborate a bit on your work on the Jewish left, and how this staunchly opposes the Zionist narrative?

Jewish Voices for Peace is an amazing movement of Jews who support Palestinian freedom. They do this with protests, fundraisers, phone banking, getting arrested—all the tools that movements use. I’ve been involved with them for years and I’ve been so moved by the work they have done since Israel began the genocide in Gaza. I was there when they did sit-ins at the Statue of Liberty and Trump Towers, and I got arrested with them shutting down the stock exchange on Wall Street. At a time when the Israeli state and its supporters use false allegations of antisemitism in order to shut up opposition to their crimes, its imperative that Jews say “not in our fucking name.”

Just as Israel seeks to weaponize our identities by saying Jew and Zionist are synonymous, it also seeks to monopolize our past. The truth is, Jewish opposition to Zionism is as old as Zionism itself. I have spent the last six years working on a history of the Jewish Labor Bund, a secular, socialist revolutionary party born in 1897. The Bund fought for the rights of Jews to live freely in Eastern Europe, even if the racist governments of the countries where they lived wanted them dead. The Bund’s membership was murdered by Hitler and Stalin, but the party’s staunch opposition to Zionism better explains the deliberate erasure of its memory. My book, Here Where We Live is Our Country, will be out next Spring.