On Not Staying Un-cried

On Kali Malone’s “Organ” at Gedächtniskirche

Charlottenburg, Berlin. Damiel is still on the ruins of the bell tower. From above, he watches us waiting. Meanwhile, we are standing in line, ready to enter the venue that will host Kali Malone’s concert. The event anticipates the release of “All Life Long”, the American composer’s latest album in which the combination of choral voices, organ and woodwinds insists once again on the desire to transcend the liturgical function of such instruments and bring them back to a primary, secular, and everyday usage.

Tonight’s concert is part of the 25th CTM festival’s programme, this year under the theme “Sustain”: a word-invitation to reflect on the capacity of sound to bridge interdependent contemporary stories, sorrows, struggles and joys. By hosting some of the most recent experimentation in the electronic field, the festival draws a map of the current state of music, letting appear—among the different threads—a clear resurgence of the ethereal and sublime sounds of sacred music, originally formalized in the Middle Ages in relation to religious ceremonies.

Profaned through operations of recontextualization, the revival of such sounds is not accidental. On the contrary, in the emphasis it casts on the mighty and spectral power that these rigorous operations can achieve, it opens a glimpse into the present condition of the world: in the face of the historical violence we are witnessing, the innumerable forms of censorship by dominant policies, and the ongoing accumulation of corpses at the expense of particular groups of people, the invisibility of ghosts thins out and, in revealing the precariousness of our lives, tells of the social body’s (un)conscious need to find space to perform mourning and heal collectively.

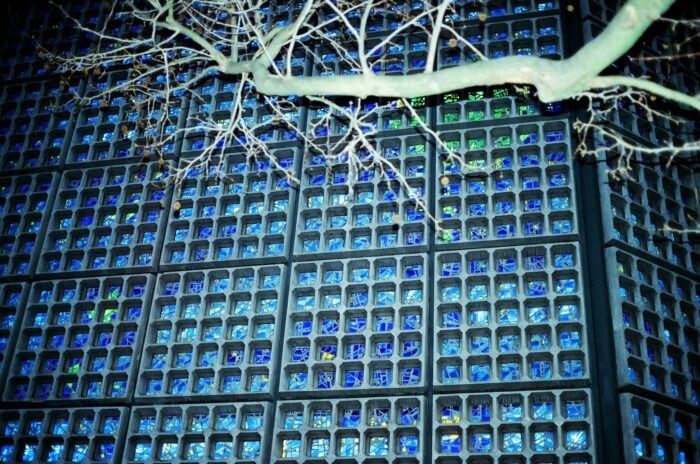

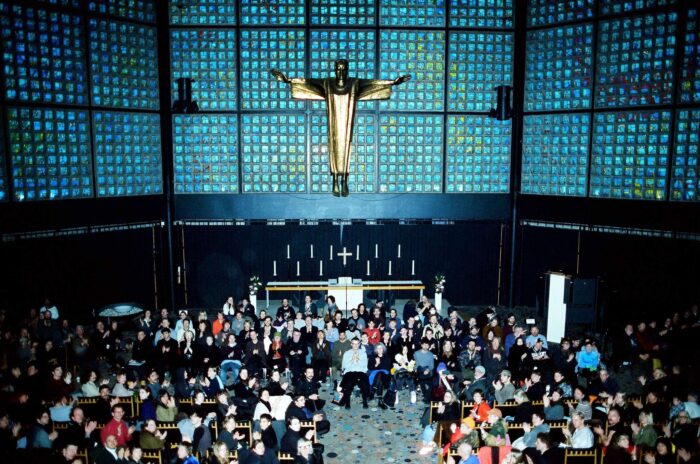

7 pm—We move in the dark once again. The air is cold to the point of tingling the skin left uncovered but, as soon as we cross the entrance, our temperatures tune into that of the church which, like a gentle ghost, welcomes us into its lap. We sit close to each other because close we want to stay. Around our bodies, a hundred other living bodies. For one night, we are a community of strangers gathered under the same sky of stones. We take off our jackets and let our eyes begin their exploration. Jumping from one stained glass insert to another, they end up resting on the massive Christ in front of us. We are in Berlin’s Kaiser-Wilhelm-Gedächtniskirche, an evangelical church rebuilt after the 1943 bombings, now a symbol of peace for Berliners; we are in the house of “angels”, while outside, “devils” keep swallowing bodies feeding the darkest nightmare of our time.

In Performing Mourning, Guy Cools argues that the best way to process the loss of a relationship is by performing the grief [1] produced in the body. To perform the sorrow and inhabit the crack to not get stuck in it. Therefore, to transform the private and inner experience of grieving into a shared and collective practice of mourning and, by performing together and recognising in the other’s weeping your weeping, to step out of the darkness of your consciousness not to stay un-cried.

In humans’ understanding of death, music has always played a central role, accompanying the various funeral ceremonies according to different social groups: a means of consolation for the living on one hand, and commemoration of the dead on the other, it has always served to soothe the grief and sustain the loss. In Western religions of the Catholic persuasion, sacred music has been the favorite since the Middle Ages. Due to its ability to construct airy and extraordinary atmospheres, it was also considered capable of delivering God’s word into the souls of the believers. In accordance with this belief, churches, abbeys and cathedrals, beyond being erected as mere functional buildings, were conceived and built to serve the function of real musical instruments. They had to resonate with the spirits and hearts of the communities that gathered within their wombs, bringing those present closer to a divine dimension. Once inside, everything had to harmonize: the sound, the glass, the stones, and the bodies themselves.

Over time, this musical expression gradually began to transcend its liturgical function and break with the Western canon that bound it strictly to ecclesiastical celebrations. In falling from the grace of religious tradition, it became a territory crossed by rhizomatic musical experimentations eager to relocate it to secular dimensions; experimentations that, like a crumpled sheet of paper, trashed classical social obligations while preserving the inherent and natural spiritual component bound to its timbres.

In a combination of drones and sacred atmospheres produced by the ethereal and vibrant breath [2] of wind instruments, new ritualistic forms have emerged. Celebratory moments capable of lifting the listener from the banality of the mundane towards contemplative dimensions that in being less fundamentalist, became also more accessible.

The fortune of this “new” genre lies in the deep and immersive nature of its sounds. The sustained and dense durations of the compositions reconnect the body to its passions and produce space to discover new yet ancestral emotions. Stretching the duration of time, they interrupt the frenetic chatter of the capitalist hyperconnection, moving backwards to alternative forms of relationalities.

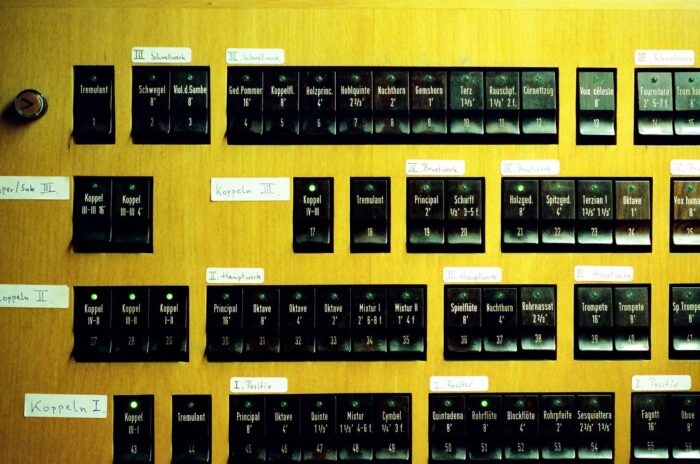

The organ behind us starts playing with four hands, moved by the fingers of Kali Malone, tonight accompanied by her partner Stephen O’Malley, guitarist and composer of Sunn O)))), KTL and Khanate, among others. The air blown by the reeds leaves the metal pipes and touches our skin like a caress. Passing through the epidermis, it enters the body, traveling into the veins, into the bones, into the organs themselves. And then back again. A feedback loop that reorganizes the sensory hierarchy and strongly connects beats to beats, bones to bones, bodies to bodies.

According to Kodwo Eshun, the physical aspect plays a fundamental role in sound experience. It is capable of reconfiguring the boundaries of the auditory space towards territories where the sovereignty of intellect is displaced in favor of more expansive and relational psychological, emotional and bodily reactions.

Suddenly, I realize I have ears everywhere and, in the tension of the sustained note, I embrace what seems to be an invitation to let go on a sonic journey that explores the depths of the individual yet communal subconscious.

Whether we want it or not, this venue becomes the temporary sanctuary in which to experience a form of worship that springs from the shared joy of listening with our bodies to a kind of music that elevates us above any rational understanding. The commonality resides in the atmosphere. Tacitly, we become a community of listeners, and sound becomes our new language. In savoring each beat and each moment of connection, we allow the transformative power of music to carry us into new soundscapes and imaginary spaces.

Moving personal and collective memories, the breath travels in and through our bodies. The air keeps pouring out of organ pipes, wheezing and wavering like a chorus of ghosts. More than human whispers burst into the real, shattering the barriers of life by intruding death, and in opening a glimpse into the present, they bring Malone’s artistic touch closer to the mode of storytelling that Juliana Martinez would call a form of spectral realism: a type of storytelling that, differently from magic realism, shifts the paradigm from what the ghost is to what it does.

Specters are said to occupy a liminal position between life, death, materiality and immateriality; in their nature absent and present at the same time, they can generate a vibration capable of deterritorializing from the spatiotemporal coordinates of modernity, infecting Western historical hegemony like a virus and leading to a state of hyper-corporeal lucidity, suggesting a more realistic and profound engagement with realities cut out by the simplifying plots of hegemonic cultural production.

The slightest variation of prolonged and sustained sounds resonates on a deep, somatic level. By evoking our memories of loss, it creates space for sharing the communal grief of people who cry out for consolation. We all reverberate and along with us, the no-longer-not-yet alive voices and specters come back; carried by the notes, they emerge into the present even stronger. Haunting, they refuse to disappear and, for a suspended time, the past, the present and the future swirl into collapse.

Crumpling on themselves, the different temporalities overlap to the point of blurring reality, dream and imagination, making it difficult to keep the boundaries of one’s personal experience separate from the bigger, contemporary historical traumas we are witnessing.

It is February 2nd, and just over a month ago, exactly on December 21st, 2023, the Berlin Senate of Culture introduced an “anti-discrimination clause” to require all state-funded cultural institutions to abide by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s (IHRA) definition of anti-Semitism, and thus also to justify war crimes at the hands of the state of Israel against the Palestinian people.

A clause that, by dangerously and shallowly overlapping anti-Zionist positions with anti-Semitic positions, was used by the German state as one of many political strategies to control, censor and erase from public and collective discourse all those in solidarity with the Palestinians. Although the clause was later withdrawn, in the following weeks and after its announcement many artists stepped out of most of Berlin’s cultural events by joining Strike Germany. [3] The scenario involved the CTM Festival itself, which, despite the politics of terror and censorship, openly supported the choice of those who revoked their participation in its programming. At the same time, it made room, probably for the first time in the city since the 7th of October, for thoughts and speech to flow freely within the public sphere.

Along many others, this event raised the question regarding what role cultural institutions should play in geographies where civil liberties are suspended, and political dissent is stifled, but moreover, it exposed the need to understand what to do with sorrow and loss when the arbitrary violence of a state does not recognize the right of certain humans to be mourned.

After all, depriving someone of the right to grieve is a hegemonic strategy for removing meaning from life itself, and thus also removing ethical awareness, dignity, humanity and love. In the same way, depriving someone of the possibility of mourning their dead/invoking them, is to remove the possibility of creating relationships—thus, also, of identifying oneself within a community and resisting along with it.

Accompanied by the organ, we sink our fingers into the story and weave together memories and facts. Absorbed in the sound dip, our bodies slip into a state of introspective hypnosis: motions of joy and immense pleasure mingle with states of deep gloom. From the depths of the belly flows back up to the surface an enigmatic pain, difficult to situate; yet, in the communal articulation and renegotiation of the pain of loss, the bond that binds us all becomes clear.

Once again Guy Cools reminds us how the feeling of grief is so similar to fear, but if the sickness of our society is that it denies mourning, tonight our tears become a political act capable of leading us toward a process of transformation and collective healing: sustained by the sacred yet profane sounds of the live performance, today more than ever, we attune to a shared rhythm; a musicality that, enhancing our feeling of belonging, holds a profound love for life, our act of resistance.

[1] Cools makes a distinction between “grief” and “mourning”. If grief is an inner and private state that we all experience at some point, mourning is an outward and public process necessary to process grief and avoid getting stuck in it.

[2] “In Greek culture breath is associated with soul and spirit. As a result, the musical expression of grief is often assigned to wind instruments such as the double-pipe or aulós, which are frequently mentioned in elegies from the classical period.” Guy Cools, Performing Mourning.

[3] Strike Germany is a strike called in January 2024 in opposition to the German state and its policies of repression against its own Palestinian population and those who stand against war crimes in Israel. In fact, since October 7, 2023, protests in solidarity with Palestine have been labeled as anti-Semitic and, therefore, continuously suppressed, cancelled and banned. The reactionary wave has also swept the cultural and academic sector, causing and persisting to cause the firing, marginalization, and shutting down of any subject whose voice opposes forms of racism, colonialism, and genocide. On the contrary, it fed an already widespread climate of anti-Arab and Islamophobic racism in German society. On the occasion of the “antidiscrimination clause”, Strike Berlin called on all culture workers to refuse to engage with German institutions that signed the clause, and to continue to fight for internationalist solidarity and the right to speak out against the ongoing genocide.