On Expanding Histories and Reversing Narratives

A conversation between Ana Vaz, Tekla Aslanishvili, Sonia D’Alto and Itamar Gov

Between July 13th and 27th, Fondazione Adolfo Pini presented the online film program “Summoning the Past and the Future to aid the Present”. Taking its title from Chris Marker’s mythical work La Jetée, the project was curated by Sonia D’Alto and Itamar Gov and featured 15 documentaries, hybrid and experimental films. Traveling between various geographies and times, the program was dedicated to the presentation of personal and collective histories, defining, exploring, challenging and reevaluating Utopias and New Utopias. Contemplating social traditions and political legacies, the films in the program highlight notions of multiperspectivity, translation and cultural interpretation, manifesting the everlasting possibility of writing and rewriting life stories. Ana Vaz and Tekla Aslanishvili are two of the 15 participants of the program.

Sonia D’Alto and Itamar Gov: Although from completely different points of view, both of your works communicate very explicitly with the notion of Utopia and official histories, while using different methodologies. Olhe bem as montanhas follows the devastating legacies of mining activities in Minas Gerais and in Nord Pas de Calais, while Scenes from Trial and Error documents the repeated attempts to build a futuristic port city in the west of Georgia. What role does Utopia play in your working process? How does it relate to official histories and narratives?

Ana Vaz: I was born in the 1980’s in Brasília, a city seemingly built to incarnate a nationalist utopian project of development and social democracy in Central-West Brazil. By the 1980’s, Brazil was still transitioning into a still frail democracy after being taken hostage to the military dictatorship that ruled the country from 1964-1985. So already here, in this brief history of the “contradictions of a new city” (to quote Joaquim Pedro de Andrade’s film of the same title), you can see how a narrative struggle around how a place—a topos—can be transformed and terraformed into an artificial political space: from a social democratic utopia to the perfect panopticon, to the military rule. For the construction of utopias, territories are stripped bare of their native soil, history and ancestry. Brasília, for example, was stripped off its native fauna for the implementation of the tropical modernism that travelled from the coast of Rio de Janeiro to the arid Central-West. So here, I would say that the issue with Utopias is precisely the U that precedes -topia, topos, place. With this in mind, I could say that almost all of my films are committed to undoing the erasures implicit in the building of any utopia. Most of them are made from a visceral relationship to the ground, to the place, the topos. Through these films, I evade the “master’s official his-tory”—one that looks from above—through looking and listening to the territory and its inhabitants in great proximity, from up close.

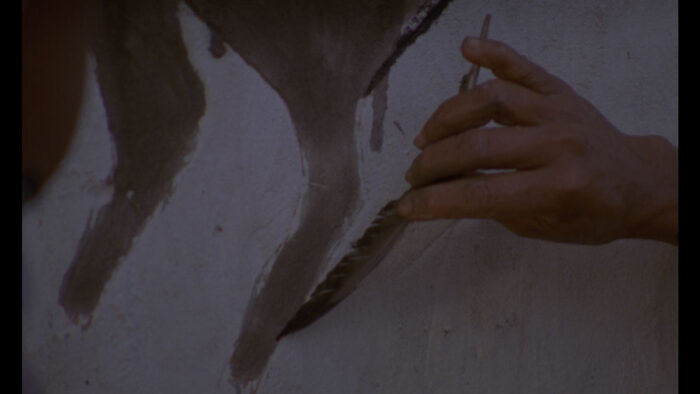

I could say that while History and its utopian accomplice surveil places and events with a wide lens, I instead choose a macro, where every minuscule detail becomes a thread to weave a history otherwise. While utopias aim to re-write the forward moving arrow of History according to their own logic, I think my films struggle to touch, hear and sense the topos, the place, the earth itself, that which is always rejected through the very first gesture of any utopia: the tabula rasa. In the case of Olhe bem as montanhas, a film split between two territories, Northern France and Minas Gerais in Brazil, my decision was to not look at these territories from afar but rather to film them from close, to create—in both a cinematic and literal sense—a close-up of these territories and its inhabitants. Yet, rather than analyzing, classifying and encoding these territories—the usual method of History and Science—I’ve decided to look instead at what Science is doing, in this case Environmental Science (particularly in Northern France), through an observation of its forms, its codes. I am observing its violence. I am looking at things very closely through images and sounds which in some ways attempt to communicate the incommunicability of these violent processes.

Tekla Aslanishvili: My initial approach to structuring the narrative of Scenes from Trial and Error was quite the opposite of what Ana just described. I was interested in a replicable model of smart infrastructures, which is completely indifferent to the social and cultural specificities and can be planted everywhere around the globe. In order to look through these contemporary forms of world-making, I’ve decided to follow the same logic of zooming out and featuring narrations which are mainly detached from the local context. But at the same time, the place itself in its passive form of existence was radiating a certain mood that communicated something entirely different from what was being said. So in the film you hear four main protagonists talking about the same space—an ever failing futuristic smart city, from different temporal, geographic and professional perspectives. But these narratives flow with and against the images of existence from the territory. And this subtle tension and mismatch between multiple linguistic descriptions and the scenes from the place is what the montage is built on.

SdA: How did you come to choose these specific study cases? How much was the final outcome of your research planned?

AV: This film was a commission made by two universities, one in Minas Gerais, the other in Hauts-de-France, about the potential relationships between these highly disparate territories, united only by a shared history of mining exploitation. However, I have to say that while making the film, everything was very intuitive. Often, I let myself be carried by the film instead of thinking that I can carry or contain the film myself. I am led by the encounters that happen as I walk along these territories. They lead me into pieces of a large puzzle. I never have access to the complete image, only to some of its fragments.

TA: Actually, I accidentally bumped into this abandoned territory a couple of years ago and at first I didn’t really know what I was looking at. The place looked like a city embryo, composed of three main pillars: a sculpture, a municipality building and the bit of the road. Later I turned back to it, because I saw the potential in the seeming insignificance of this place. I started developing a work on aesthetics of smart city infrastructures around this urban triangle that would serve as a metaphor. But once I started filming, the second trial of the city development was announced, so I ended up following the process for the next two years, to its ultimate failure.

SdA: What I liked in both the films was the fact that even though you principally follow people, they all seem like a kind of ghost figures, while the real protagonists are the nature, the animals, even the infrastructure itself.

TA: There were several decisions that I had made already before starting to film on site. Abstaining from directing my camera at people who are stripped of their voices, was one of the working principles. Instead, I was interested in finding other forms through which the present conditions of anticipation, uncertainty and ambition could shine through. The Architectural form in the film serves as one of such mediums. The municipality building, for instance, is a structure that is very ambitious in its form, and it communicates the ideas of total flexibility and adaptability. It simulates the random composition of architectural forms by fixing them in the air. So in a way it is a sculpture of the dominant future imaginary, the one that escapes endings through its seeming ability of mutation. But through its ruination the structure also points towards the endings and failures that accompany such technological urban fantasies. The aesthetic act of speculation on both positive and negative turns of events, creates moments of empathy and understanding towards the complex regimes of existence on this territory.

IG: It’s very interesting to consider these moments of empathy that you describe while still keeping in mind the greater context in which both your films take place. It takes us back to the discussion about official histories and myths.

TA: I find the theme of your film program very intriguing—the notion of summoning the past and future in help of the present. When I was researching for the film, it was very interesting to observe how both private companies and the government invent and twist the past to promote their interest. They source their materials not only from geopolitical, but also from mythological and cultural histories. My favorite story in the context of Anaklia is how the Georgian president, Mikheil Saakashvili used the Greek Mythology to create a certain folkloric vibe around his idea of building a futuristic city. According to the semi-mythical story that he told to the journalists in 2011, he was sailing in the waters alongside Anaklia without knowing the area, when his boat suddenly broke down and he and his crew were about to drown, when thankfully the Anaklian fishermen came to save him. And in this moment of salvation from the sea he saw the infinite beauty of the place and realized its infinite potential for economic growth. This story resonates directly with the myth of the Argonauts whose leader, Jason, was also saved by fisherman to discover the resource-rich Kingdom of Colchis, the territory in which Anaklia is located today.

This is where myth meets contemporary politics. With this story Saakashvili placed himself within the mythological history of Georgia in order to push his future vision forward. And in the context of your film program I was thinking about what Keller Easterling is suggesting in her book Medium Design. The truth and rightful activism is too weak against the totalitarian gurus, who by multiplying lies and falsifying histories create slippery surfaces on which rationality loses its balance. She suggests that histories are always expanded to include things that never really happened. The understanding of this kind of speculation and play with different temporalities and narratives could in fact support us in shaping our present. This was one of the elements that became very evident while looking at the history of the area. I imagine that Ana also encountered that during her research, stories and elements that are completely invented or adjusted in order to allow desired futures to happen.

AV: Yes, very much so. As much the narrative of Western modernity imposes itself and its violence across vast territories on this planet, I am always surprised to witness how frail and false are its premises. With each of my films and the territories they inhabit, I am always surprised at a polyphonic cacophony of narratives that contradict any idea of an official History. In the origin of the word official is office, authority, the State. So I would say that in my films, I am often trying to cross the margins of the State, where it becomes spectral, or simply absent. This is why I often avoid officializing the narratives of the territories present in these films—where we are, why and with whom—and this is a strategy because you don’t really need this in order to understand, to feel, to sense what’s going on screen. I convoke the sensorium as the place for a counter narrative. We can’t invent one while only using rationality. There is no invention with the same means of modernity. The master’s narrative is a narrative of domestication. And I think that a lot of my films are either witnessing, or trying to move away from this domestication. The majority of my work is about looking back and excavating the ashes, the untamed strata of the territories in which they are situated. Mostly they are set in Central-West Brazil where I was born and brought up, these films are often haunted by strong retinal and historical specters from this region. Yet, because I have left many years ago, I am always somewhat in between, neither completely native nor foreign to these territories.

IG: I’m very curious about this notion that you bring up, of being between two worlds—you already left your home country so you are not part of it anymore but in fact you will never be fully part of the new place you chose to live in. Where do you see yourself within this equation, Tekla?

TA: Well, I moved to Berlin in 2011, so I’m here for almost ten years now. The transition was very heavy; I felt alien for a very long time. Only recently I started to really accept myself and my state as a migrant. But of course I still see myself as being between these two places, Berlin and Tbilisi. Berlin, in the end, is a place of isolation, but at least it provides some opportunities for cultural production. In Georgia I would have never been able to work as I do here, unless I built a stable infrastructure of support together with my friends and colleagues—it’s a rather old dream of the Georgian artistic diaspora in Berlin. What I’ve been practicing for a few years now is collaborating on a horizontal level—I work a lot with other filmmakers and people who produce knowledge in different fields, and we share all the means we have, be it technical or intellectual. We are living in a time of uncertainty and massive exhaustion; mental health problems, depression and burnout hunt everyone around me. So creating support infrastructures based on care, exchange and mutual respect is very important at the moment.

SdA: We are living a very exciting moment, where many people are forming collectives, looking for ways to establish sustainable platforms for creation, alternative systems. Which is obviously based on alternative narratives—I find it very interesting to see counter narratives in terms of resources.

AV: We are living through a moment of a certain lucidity, a change in perspective in regards to the violences of the systems we inhabit, one which has torn our relations to the earth itself through its endless exploitation of subjugated bodies-as-resources. Yet, I don’t believe discourses of care and reparation can be used as an easy method or reversal process. This reparation is about attentive and ever-evolving work, a lot of it. Good intentions are not enough and can be toxic. Often, they try to reinstate heroic and salvation discourses inherent to the very violence that they aim at undoing. If you think for example about the importance of the colonial statues being taken down at the moment, and how strong and important it is to really reassess the presence of these monuments on our our (sub)conscious, on our understanding (or lack thereof) of the histories which they celebrate, is huge. However, I don’t think you topple down statues in order to build new ones. Isn’t the very foundation of heroism an issue to be challenged? I’m resistant to trying to find a method or a solution. Rather, I feel it is essential to listen, to be attentive to the transformations around and in us. To be attentive is not a passive way of being in the world. To be listening and looking, going back to the beginning of our conversation, is exactly what cinema is capable of doing.