On a Wildflower-lined Gravel Track

A conversation with Forever Informed

Forever Informed was a collective project by Lower Levant Company (Peter Eramian, Emiddio Vasquez), Endrosia Collective (Andreas Andronikou, Marina Ashioti, Niki Charalambous, Doris Mari Demetriadou, Irini Khenkin, Rafailia Tsiridou, Alexandros Xenophontos), and Haig Aivazian, conceived for The Cyprus Pavilion at the Venice Biennale 2024.

This long conversation dives deeper into the project, along with the review that anticipated it, and both pieces stand as witnesses of this experience. Despite the space has closed the vision still lingers, as the discourses remain open and relevant.

Alessandro Cazzola: In early December 2024 I spent a few days in Limassol, and one evening a green laser beamed in the sky. It wasn’t moving, it was up there while clouds were overpassing it. I couldn’t stop fantasizing about some sort of attack, either military or extraterrestrial. I soon realized how inclined to such violent and paranormal speculations I became after familiarizing with the Cypriot landscape. Here, traces of internal conflicts are still visible while echoes of local ongoing wars are tangible. To complete the panorama, a widespread skyline of antennas, cameras, video-surveillance systems, and geo-tracking devices form the visible apparatus of covert operations related to intelligence interceptions and data transmissions that interests the region. Moving between sense of constant control and unpredictable events, which are the conceptual premises of your collaborative project for the Cyprus Pavilion? In the exhibition, Forever Informed brought to light stories that oscillate between real events and fictional ones. How did you balance this narration in relation to sociopolitical forms of “ghosting” in the Levant and games of power between nation states and citizens?

Forever Informed: What’s interesting about these fantasies and speculations you speak about, is that the paranoia we’re inclined to attach to a paranormal or an extraterrestrial event often has this curious quality of excitement, a sensationalism that’s more comfortable to settle into and indulge in—it’s how conspiracy theories gain momentum. Conspiracy may very well begin from what the late Frederic Jameson described as “the poor person’s cognitive mapping in the postmodern age” that desperately tries to represent the total logic of late capital, but the instances where power rears its head in seemingly mundane, inconspicuous surroundings, like the one referenced in our title, the paranoid impulse is one that beckons us down these rabbit holes.

A way that paranoia seeped into our conversations during this project was through Eve Sedgwick, specifically her conception of it as a mode of reading and analysis. Paranoia as this anticipatory state of hypervigilance that’s predicated on inevitability—thinking that it always has, is, and will be this way. It was important for us to draw from her call for readings that are reparative, which also require a dose of paranoia, but offer productive, political ways forward that are open to non-linear time, that are better adapted to contingency. This also gave way to the use of fiction within the works and their different modes of storytelling, a seed that was planted with the short story that started it all:

On a wildflower-lined gravel track off a quiet thoroughfare, a parked black van scans its surroundings for personal devices to send out a thumbnail from the account of a recently deceased person. Captioned “OMG! Have you seen this?!”, it reaches three unsuspecting acquaintances. In disbelief, the first recipient takes the bait and clicks the link. The second fails to see the notification as it drowns in a sea of information debris. The third—no longer friends with the ”sender” and unaware of their passing — sees the message and opts not to answer, effectively ghosting them. […] So our ghost story goes, and so it echoes: On which side of the screen lies the ghost?

Fiction requires at least a momentary suspension of disbelief that’s also necessary for committing to the type of ghost(-ing) that the project calls for. Sometimes, vernacular language and internet slang have a way of inadvertently distilling the social imaginary and its ideological shifts. Indications of such a shift took place most notably in the pandemic, during which we saw an increase in manifesting and a return to spiritual practices and the use of “ghost” as an adjective to describe social relations as they became increasingly mediated in platform economies, as a result of social isolation: ghost kitchens on food delivery apps, ghost producers populating music streaming platforms, ghost traders on investment and stock trading apps, ghost cities after Airbnb. Like our story, this seemingly benign adjective served as ways to underpin a typology of new ghost-like figures that haunt present socio-economic relations.

In order to speak about such ghosts, which are understood as absences first, Rene Daumal alludes to a science of phantasmology. Following a pataphysical methodology, he articulates the problem of approaching a ghost by what’s assigned to the beings surrounding it. In other words, ghosts are holes defined by their peripheries to which we often assign qualities. In the case of technology, this could mean that its ghosts emerge with technological breakthroughs just as much as they’re prone to break through the cracks of technology’s own breakdowns. This is just one of the many contradictory allegories relating to ghosts and technology.

Which brings us to ghost-ing, which by definition, takes shape through paradox: it’s an act of inaction, a decision to withdraw and abruptly end communication with someone, often enabled by being inundated with constant noise online. What would it mean to then resist the excess of information, and what other meanings could ghosting acquire? What does the archetype of ghosts actually do, if not to return and haunt the present? This is what we learned from Avery Gordon’s Ghostly Matters, leading us to shift the gesture of ghosting as withdrawal into an imperative of remaining vigilant.

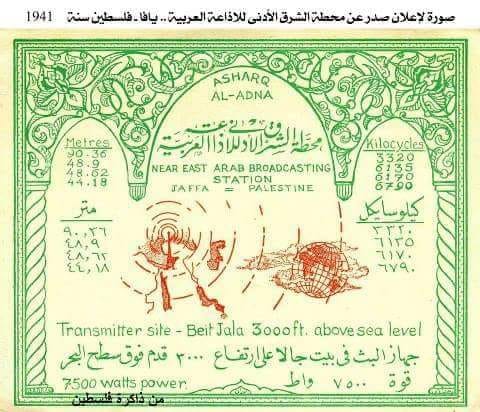

With ghosting as a framework of thinking about history, and then reflecting upon a ghost’s periphery, the final conceptual thread that became crucial for the pavilion was how these translate to specific geopolitical dimensions. Aware of the intrinsic problems of a national pavilion we began to approach the question of a nation-state through the notions of proxy and proximity, as indicative of a new type of warfare that is, in part, the direct outcome of technological advancements in information and transmission infrastructures. Looking at the covert operations that have been taking place historically in Cyprus, we began considering its instrumentalisation as an “antenna island” at first, through its proximity to the Middle East, and as a listening post, by proxy, to ongoing intelligence interception on a global scale. Cyprus’ ability to accommodate both, as a friend and a foe in the region, encapsulates a contradictory stance whose true repercussions, though felt like ghostly presences, have yet to fully materialise.

AC: Many of the exhibited artworks referred to geological, cultural and natural archaeologies. Red Polished ware is one of the best known pottery production in Cypriot history, whose technique and decorative patterns were likely acquired from people who migrated from mainland Anatolia during the Bronze Age; Copper extraction and its trade in the Mediterranean are the reasons of Cyprus’s economic fortune in ancient times, leading to etymological overlapping between the name of the island and Cuprum, Latin word for “copper”; Seashells have been used since the Neolithic as personal ornaments; Sand is one of the main aggregate to produce concrete; And olive trees are wooden remnants of the deforestation the island was subject to. In the exhibition, references to the ancient world and its raw materials intermingled with criticism for modern aggressive activities of extraction, land consumption and related economic-driving industries, such as (mass) tourism and export goods. Given this complex contemporary scenario, how does your call to the land care differ from others in such a contradictory frame that was the 60th Biennale in Venice? Forever Informed has transformed these raw materials into transmitting vessels symbol of the Mediterranean flora and landscape. What is the role of ancient Mediterranean heritage and mythology in this action?

FI: We treated these materials you mention as memory reservoirs that can carry a certain symbolic potential and instigate further excavation into histories and their sedimentations. In this sense, some of the works were approached from an archeological-like stance that relied on matter’s own ability to communicate things from the past across time scales, media and traditions; from deep geological events, to historical processes, seasonal changes and digital ephemera. But we also didn’t want to to fixate on bare materiality or fetishize its provenance, as we are aware how these material traits are often co-opted by the same type of agency we fictionalize in the first two rooms of the pavilion, and are celebrated in art events like the Venice Biennale. So, more than a reference to Mediterranean flora, a wildflower by its very nature, is an invasive force that cannot be tamed, contained or stopped, resisting its very landscape, one that’s increasingly disrupted by aggressive extraction and rapid urbanisation. From the contradistinction of these two approaches to materiality came our approach towards the land, and to that effect, a call to care, where poetic forms of resistance were set up to challenge generic understandings of ecology, whose failure to engage with the question of technology lead to more traditionalist values.

On that last point, we also took note of Cypriot authorities’ symptomatic use of mythological figures to categorise infrastructures (KINYRAS), neo-extractivist operations (Aphrodite Gas Field), surveillance projects (CYCLOPS) that obfuscate the reality of their criminal complicity (Amalthea) in covert operations (Pegasus). A return to tradition through mythology is all too often a conservative aesthetics of choice and shift indicators towards fascist regimes to which Venice Biennale has been historically anything but impervious to; but, we also think that there is something else at stake. If Greek thought and Western tradition at large—rationalism, the polis, democracy—begin with the end of mythopoesis, then the contemporary return to mythological tropes in the descriptions above is indicative of a more general semantic dissolution of politics and economics. Inversions of mythology capitalise on this, and by performing anachronisms, they reinstate a fictional arc of historical continuity bootstrapping the present to a bygone era. In this sense, while mythology counters modernity’s project, its inverse—under the guise of “innovation”—ends up serving the financial agendas of neoliberal governance.

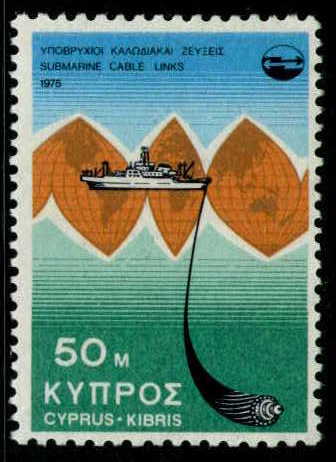

AC: A subsea cable dashed from the canal to the inner space of the pavilion, appearing and disappearing in different forms of representations. The pipe reminds us that most part of global telecommunications travel underwater, many of their tracts being located in geopolitical unstable areas. Recent international sabotages to marine infrastructures are episodes that picture strategies of the current hybrid global war. In the Baltic Sea, telecommunication cables have been sheared off in November 2024 and data cable Eastlink 2 has been blown up in December 2024. Another critical spot is the Red Sea, where cables connecting Europe, Africa and Asia are threatened by Houthi attacks to international maritime traffic. In the performance Myrrha, held during the period of exhibition, you depicted a future scenario staging the collapse of KINYRAS, a domestic subsea cable for communication running along the coast of Cyprus. Shifting again between real and fictional events, it emerges a focus on subterranean activities, modes of extractivism, and now subsea transits. What does this “underworld” mean to you? Within the investigation on visible/invisible related to telecommunication, where does the social practice of “ghosting” (which is mostly conducted digitally) position itself?

FI: Generally speaking, the underworld can be such a potent place to think in because it conjures such a multitude of connotations. The idea of a cavernous, nightmarish place, an inverted world bubbling beneath. There’s the more conventional associations with myth and legend, of the underworld as a violent consequence of sin, then there’s criminal underworlds, counter-cultural and queer underworlds in climates of deep repression, so on and so forth. The world beneath the waves though, that’s a real place. It’s virtually inaccessible, under pressure and without any light, but it’s a place, and one that is predicted to be the new frontier for geological exploitation and immeasurable ecological catastrophes. And as you mention, it has become a place of key geopolitical relevance.

In thinking about the material nature of digital infrastructures and communication networks, that the seabed is instrumentalised as the place where the backbone of global communication resides, it allows the global financial system to stay afloat, funnily enough. There is a historical and material continuity in infrastructures, something that Tung Hui-Hu talks about at length in A Prehistory of the Cloud. The telegraph lines laid by colonial empires to be connected with colonies run parallel, at times quite literally, to telephone ones, fibre optics and trade routes. We’ve already talked about how these communication cables carry whimsical names that stem from ancient mythology, but since we’re talking underworlds too, the first telegraph to be sent across the Atlantic becomes almost ironic: “Glory to God in the highest; on earth, peace and good will toward men”.

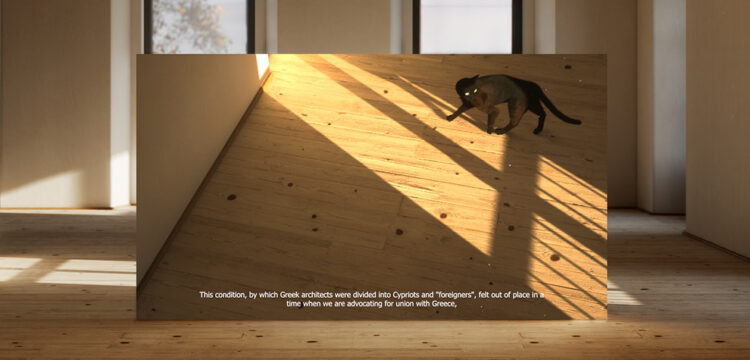

Creating a metaphorical space that connects some of these underworldly qualities, this is where we (the Endrosia artists that devised Myrrha) contemplated how ghosts consistently resist to be assimilated in established continuums, and staged a form of sabotage through the idea of a breakdown, a short-circuit, to demand that what’s invisible is felt and to negotiate the terms of the extractive agreements of death as an industry. The abject qualities of both Myrrha and Medea as they’re represented in mythology started to make sense as equivocal vehicles to articulate these tensions, to collapse time on the basis of vengeful haunting.

At the same time, this underworld is a direct byproduct of systems of power—corporations, public bodies and agencies—that maintain, construct and exploit the resources flowing through infrastructures. In the case of Cyprus, and particularly with regards to telecommunication infrastructures, we are talking about endeavours that, through coloniality, persist across policy and varying scales of influence. Being a strategic post for all sorts of foreign military interventions, Cyprus’ infrastructural extensions to the Levant are regularly compromised and have become part and parcel of US and UK foreign policy in the region, as per the Snowden revelations in 2011-13. Ghosting, in this context, alludes both to these covert operations, but again, our intention for the project has been to move beyond the paranoid reading of surveillance, and dwelling in this underworld, taking on the task to build nodes, networks and alliances with the region that put assumed histories to question.

AC: A cable channeling the undulating tones of water and wind of Venetian canals, a morse code blinking the sentence “Tomorrow morning you will see”, ceramic horn speakers, video narrative sound, and electrophonic noise. These single elements contributed to the creation of a unique soundscape within the Cyprus Pavilion, spreading from the canal to the indoor space until the courtyard. It seems to me that sound was the key element linking artists, artworks and visitors. Do you agree with this interpretation? Sound as connector of natural and artificial spaces, as well as the mental and physical ones. Somehow, it brought Cyprus in Venice. Based on your experience for the Cyprus Pavilion, what is the potential of sound in an art exhibition?

FI: While we employed several decisions and techniques to connect artists and works, sound did play an important role in the project. As a medium that tends to be misperceived as immaterial, it had a way of setting the mood throughout the space while being conducive to sensing the “other side.” What appeared first as an inconspicuous reception room of a start-up with zen-like qualities and new age ambient music, shifted into resonances coming from a listening outpost set up to receive Venice’s ever-changing soundscape. The agency’s “reception” room transformed into an eerie reception vessel. Like the agency’s own ambition denoted in its name, Forever Informed, this constant reception is not unlike the NSA/GCHQ policies of gathering information in the region (“Collect it all”). But if there are lessons to be drawn from mythology, one would be that Promethean ambitions of this scale always fold to their fallacies; recent developments in the AI arms race revealed just that. Therefore, in the project, detecting sound through multiple speakers, microphones and sensors, doubled down as a way of thinking about how the so-called immateriality of sound, just like the one shared by information, is transmitted and registered across different spaces; how sound and information re-materialize.

This was also another property of sound’s materiality that we wanted to explore: its ability to fold architectures, temporalities, histories and cultures into proximity with one another and into productive dialogues. Walking or stopping through the pavilion became almost a form of mixing or equalizing these resonances according to one’s predisposition to attention and receptivity. Listening to encoded noise messages on headphones or listening to bat calls through horn speakers, but also feeling the bodily sensation of sub frequencies throbbing from the bass of a club song, or, being abruptly surrounded by the resonances of church bells across the canal. This openness towards contingency, that refutes many of the calculative logics of control and containment (that characterize paranoia), are some of the affordances of sound which—outside and inside, through internal and external experience—keeps shifting and decentering one’s position.

Sound has been having its moment in the arts, and even though it comes with certain challenges to share spaces with other works, it has been increasingly present in gallery spaces. Since for our project the works were considered and produced in relation to one another, sound was accordingly molded to complement the themes and questions we were engaging with, from field recordings on sites of interest to the styles and techniques of its production (ie. spectral treatment). There is a lot in the history of sound production and its transmission that is often difficult to translate materially, but that is one of sound’s own historicity we wanted to explore in the project. In its materiality, sound’s potential to shift and fold the listener’s position, towards recalibrating their senses, also suggests that ghosting, and the commitment to remaining vigilant, entails new auralities.

AC: The exhibition expanded its borders towards Lebanon, Palestine and Egypt, by including stories of surveillance, transmitting stations and broadcasting services operating during the 20th century across Cyprus and the neighboring territories. In European historical and socio-political narration, Cyprus is usually analyzed in relation to the actors who reclaim sovereignty on its territory (Greece, Turkey, the United Kingdom and UN peacekeeper forces). You had finally shifted this focus towards its geographical region of belonging, demonstrating the need and urge of contextualizing Cyprus within this frame. Can you help us understand where does this sense of belonging come from, beyond mere geographical reasons? Referring specifically to the art world, what is the role of Cypriot art community today within this scenario?

FI: Let’s say that it would take tectonic-plate shifting forces to trigger the profound ideological shifts needed to end the island’s perpetual leaning towards/looking up to the West. Whether institutionally or culturally, whether it’s a question of sovereignty, identity or belonging, the Eurocentric impulse in the Cypriot context is more than just ubiquitous, kept alive by ethnonationalist claims to “Greekness” in the south, but also through a perhaps more apprehensive reach towards the island’s entry into the European Union. But there are also people that understand the need of engaging with the “post-”colonial project and the nuances that entails, to recognise how imperative it is to shift our focus from looking up, awe-stricken, towards the West, which lies much further, and redirect it intently on our closer neighbours in the East. In our publication, we included full translations in the nonstandard vernaculars of Cypriot Greek and Cypriot Turkish which are seen as culturally inferior to the official, institutional languages of standard Greek and Turkish. It’s a choice that, on paper, isn’t all that radical. It nevertheless became fodder for populist MPs who, upon receiving word that this choice was made by an institutionally-backed national representation of artists, saw the move as offensive enough to release official statements, as though Cypriot exported goods were being spoiled by not certifying as Greek-adjacent enough.

The more collective approaches stemming out of the Cypriot art community attest to our need to connect and forge a sense of belonging and reflection within such a stifling political climate. Endrosia is one example of a strife towards such a commons. When the Cypriot phrase “en drosia” is spoken, usually at the peak of summer and after dusk, it implies a sense of relief prompted by a breeze that can sometimes pierce through the island’s asphyxiating heat. The origins of the collective’s name become a metaphor for a practice that seeks to shapeshift and follow fluid streams of thought often tied to decolonial, queer and feminist concerns. In the case of Lower Levant Company (Emiddio Vasquez & Peter Eramian) there is a clear agenda to shift the geopolitical and economic focus as mentioned earlier, by recontextualising Cyprus as part of the Levant, a status that has been waning since Cyprus entered the European Union in 2004, even though geographically, culturally and historically the island is very much part of the Levant. The name puts a new spin on the Levant Company, a 16th Century English chartered company of merchants trading in the Levant seas, which was instrumental in the colonisation of the “New World” and served as a model for first wave capitalism in the region. The inclusion of “Lower” in the name emphasizes the project’s commitment to practices of material and political regrounding, further reorienting our focus towards the land, subterranean activities, and modes of extractivism.

In relation to the art world and art communities in Cyprus, efforts to create bridges towards the East and South (or more appropriately the MENA or SWANA regions) have been taking place more and more lately. In fact, Peter Eramian first met Haig Aivazian during the Home Workspace Programme at Ashkal Alwan in Beirut back in 2018 and later invited Haig to Cyprus for a presentation of his work at Thkio Ppalies, the art space he runs together with Stelios Kallinkou. Such exchanges are vital and create other chain reactions that prove themselves transformative. To be honest, we are still not sure what “art world” really means. Often what is forefronted when thinking of this “world” (as if it exists in a vacuum), are the markets and economies associated with it. We prefer to think less in these terms and more in terms of discourses and political urgencies, finding “allies” per se and thinking of art not as a commodity, or the potential pitfalls of art for art’s sake, and more as a discursive vessel for exchanging ideas and creating new communities of resistance. That’s not to say we don’t appreciate art in all its forms, but that this is how we choose to think of art and the only way we felt we could respond to the problems of a context such as the Biennale. With the ongoing genocide in Palestine, it was impossible to think otherwise. So, yes, as you rightly point out, we are questioning the administered ideological narratives that define our sense of belonging as “Western” and actively shifting our focus (sometimes referred to as “unlearning”). Since some of us have been doing this for some time now in Cyprus, bridges with Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt and other places in the region are indeed slowly growing and being nurtured. We would like to think this is only the beginning and that this reorientation (which, to clarify, is happening across many circles in Cyprus) will eventually contribute to transforming the wider cultural sensibility of what it means to be Cypriot.

AC: For the duration of the Biennale, you have integrated a Vigil Workspace within the exhibition. Researchers, practitioners, and the exhibiting artists have contributed with performances, writings workshops, rituals and sound experimentations. You have conceived independent residencies, conceptually fully integrated within the broader project, that represented indeed one of its most original aspects. More specifically, I have appreciated the metaphorical shift from the labor of invigilation towards the politics of remaining vigil today. A sort of awaking tool against a common sense of drowsiness, that interests the contemporary art system as well, where some of its weaknesses are deliberately ignored. Invigilators, the “ghosts” amongst all art workers, may represent entire categories of art professionals who struggle against low salaries, precarious contracts, and political interferences. What is the value given today to art workers and in general to the cultural industry? How can such a rich program as the Vigil Workshops help drawing attention to the “ghosts” of the art system?

FI: Many of the age-old myths and clichés surrounding art, such as the romanticisation of the artist or the art object as thing-in-itself (fetishisation) seem to still persist. This might be because these positions have been appropriated very neatly by capitalist logic and the commodification of art. In parallel, we have the attention economy in full speed where everything becomes a punchline, and little to no time is afforded towards caring, reflecting or spending time with art and creating communities around it. As you rightly point out, there is a sense of drowsiness or disenchantment that comes with viewing art nowadays that can be very unwelcoming or alienating, which is often reflected in, or perhaps even due to, the precarious conditions of art workers, top-down hierarchical institutional structures and market-driven decision making.

We wanted to create an exhibition environment that eschewed many of these misbeliefs and “standard practices.” From the get-go, it was important for us to work collectively and horizontally, avoiding the standard curator/artist model. We found ourselves confronted with the contrast between the often neglected “passive” role of the invigilator, sitting in a corner “guarding” artworks, and the active role of being in vigil or vigilant (to stay awake, be watchful). Then there is also the practice of holding a vigil, a gathering that creates a space of remembrance or solidarity following a tragedy. These definitions came together with our own rendition of the in-vigil-ator. So we decided to embody the dual figure of artist/invigilator, a role that we are all too familiar with. This arrangement allowed us to establish a relationship of care with the space and the artworks, a responsibility we would have otherwise been severed from. We didn’t want the project to finish with the opening of the exhibition, like a product packed and ready to go. For us, creating the conditions for direct interaction between artist and viewer was valuable and facilitated an important space of reflection, discussion and remembrance. This also gave us the opportunity to connect with people from all over the world with practices and concerns similar to ours, advancing the discourses of the project as well as our own practices.

The Vigil Workspace, a workspace we designed as part of the exhibition space for hosting invigilators, held copies of our publication as well as resources available on Learning Palestine, facilitated in alliance with ANGA (Art Not Genocide Alliance), as well as both volumes of “The Black Book of Pushbacks” (also available online: volume 01 & volume 02), by the Border Violence Monitoring Network, documenting pushbacks and cases of border violence. The Vigil Workspace, also the name of our parallel events programme, hosted two guest researchers—a member of the Border Violence Monitoring Network and artist/writer Miriam Gatt—and presented four performances. These activations were vital for us, as we were adamant from the beginning that we wanted the project to stay discursively active and keep generating (and re-generating) throughout the Biennale.

AC: Forever Informed is the name of an ambiguous shell company, which takes over the space of the Cyprus Pavilion. It embodies both fictional and real stories, told by the exhibited artworks. Could you explain meanings and missions of Forever Informed? How many people are involved in this project and how do you balance the collaboration between such a multifaceted group? The space seems to represent the actual prerogative for the existence and activity of Forever Informed. What’s the role of the space then? How do you envision a Forever Informed future and can you anticipate the projects you are working on?

FI: Concerning the nexus of fiction and the real, our decision to use parafictional devices and modes of address to speak about Cyprus, Lebanon and their vicinity also ran the risk of trivializing the severity of the present moment and the state of the world we found ourselves confronted with. This is why throughout the duration of the project we kept revisiting some questions that Hal Foster posed in his essay Real Fictions regarding the need or desire to resort to fiction in order to frame the real, of posing alternative futures as a response to the dominance of financial futures as time is being mortgaged to a “time to come” (a time that never actually arrives).

At first, as a façade, a prophecy and a vice, Forever Informed guided us through the events that we wanted to interrogate, turning into an outer shell that deflected institutional attention and protected us along the way. But it quickly became more than that. As a group identity for a collective of seven, a duo and a solo artist, it catalyzed our collaboration by allowing us to tap into the agency’s fictional ambitions, aesthetics and inevitable demise, to then further our respective research into the “real.” However, the more we delved into histories, we also realized that there is always, already, a certain degree of fictionalizing the past to which we inadvertently assign more reality; history, not as the reproduction of past reality but closer to the “fiction of the factual.” In this respect, then, Forever Informed and its declaration for omniscience, turned itself into a mode of investigation, down endless rabbit holes and uncanny “stranger-than-fiction” coincidences, to endorse the para-historical, as legitimate narratives, in the same way that the paranormal is often frowned upon. Ultimately, to be forever informed requires a forging of new narratives out of history’s paraphernalia, an aspiration towards modes similar to Saidiya Hartman’s critical fabulation.

Allow us to circumvent the question of Forever Informed’s future for now. More will be revealed in due time. Subscribe to the Forever Informed newsletter (foreverinformed.com) and remember, when in doubt, smart solutions to weak signals are forever at hand.

The Lower Levant Company (LLC) is a project by Emiddio Vasquez and Peter Eramian that investigates Cyprus’ geopolitical and economic activities, through its affiliations across the Levant and beyond.

The Levant Company, after which the project is named, served as a model for first wave capitalism in the region. By establishing trading alliances between the British, Venetians and the Ottoman Empire in the late 16th century and setting up factories in the Eastern Mediterranean, the company was instrumental in the colonisation of the New World. Despite its eventual demise, the company’s structure prefigures the contemporary organisation of financial capital in the region, but also the very historical developments of Cyprus towards its independence. In that sense, LLC considers ways to recontextualise the geopolitical forces that still permeate the island across scales and agencies, while challenging the westernising narratives that exclude Cyprus from its cultural and geographic vicinity.

The inclusion of “Lower” in the name recalibrates the company’s originary ambitions to the project’s own commitment to a practice of material and political regrounding; one that reorients its scope in relation to the land, subterranean activities, and modes of extractivism that operate in the present moment.

Haig Aivazian is an artist living in Beirut. Working across a range of media and modes of address, he delves into the ways in which power embeds, affects and moves people, objects, animals, landscape and architecture. Aivazian explores apparatuses of control and sovereignty in sports, museums, the office, music and anywhere else they may be at work.

Endrosia was established in 2018 as an artist-run project space by Alexandros Xenophontos. Since 2021, Endrosia has been operating as a collective of seven practitioners (Andreas Andronikou, Marina Ashioti, Niki Charalambous, Doris Mari Demetriadou, Irini Khenkin, Rafailia Tsiridou, Alexandros Xenophontos) bringing together a wide spectrum of disciplines through cross-functional processes across exhibitions, spatial activations, printed matter and performance.

The collective is named after a Cypriot phrase that expresses a sense of relief prompted by a cool breeze, a “drosia” that haphazardly seeps through the humidity that is characteristic of our climate. A breeze makes itself felt, be it arbitrarily, even in the most asphyxiating temperatures; a reminder that humidity is not always impenetrable.