Of Fools

Benni Bosetto, 2016–2022: it ends with Stultifera

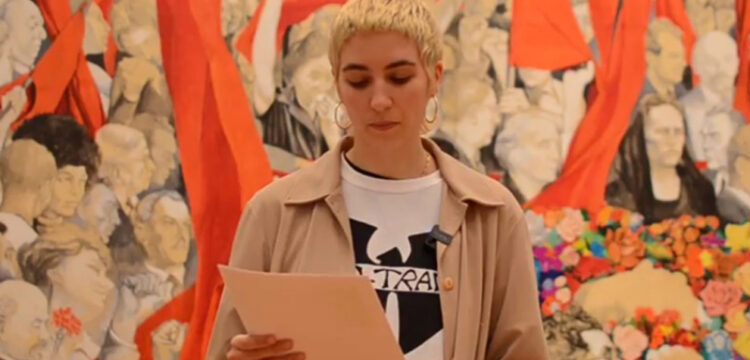

Stultifera is a performative work conceived by Benni Bosetto on the occasion of ART CITY Bologna 2022 that found a space in the Salone degli Incamminati of the Pinacoteca Nazionale di Bologna. The work starts from the subject of Sebastian Brant’s Ship of Fools, a satirical allegory published in 1914, and attempts to overturn its moral critique and reflect on the potential of the “fool” focusing on their lack of fear and thus on the generative dynamics of their instinctiveness.

My first conversation with Benni Bosetto took place in a small Milanese bar, among the tables of a relatively anonymous outdoor area, at the beginning of summer 2016. I remember we talked about “narration”, the need to build an open space where rules, principles, habitual thinking, and representative codes could be questioned without reducing the imaginative plane, rather it would be the starting point and would emerge forcefully. Shortly after that, Florida—Benni’s first solo exhibition in the TILE project space—opened in September. Bosetto created a fictitious environment, drawn on white paper that almost completely covered the walls and floor. Two girls lay on opposite sides of the room, posed as if daydreaming, a non-contemplative but highly productive state of mind in which the imagination is at work developing new visions. The audience thus witnessed an imagined space, still in black and white, a proliferating visualization of that open space we were looking for.

Bosetto’s research on the potential of pre-logical thought began to take shape, leading her to investigate different cultures’ beliefs and ritualistic practices with an almost anthropological approach. At this time, she built up her use of drawing, through which she modified the sources and images she studied to construct a personal language incorporated within other visual codes. Drawing becomes a grammar, linked not only to line and gesture but comprising iconographic references transformed into mythemes to be repeated and modified. Some examples of this approach are her works between 2017 and 2019, such as Sweep Away Sweep Anyway the End of the World Will Never Come (Ibiza, 2017) twenty drawings framed the cloister of the Eivissa town hall, recounting shared rituals in which the body was reassessed through its fluids. Studying the ritual world bordering myth and reality allowed Bosetto to connect with other visions of the body, in line with the organic world to which it belongs. The body is a temple assembled through social practices (Judith Butler; Michel Foucault). Nevertheless, it can be called into question through its dematerialization, scattered into sculptural units that reproduce forms of simple organisms. Accordingly, Bosetto’s sculptural work has continued her research into the realm of rituals as a narrative dimension capable of generating new identities, making scepters (Le streghette, 2018), sticks (Quattro bastoni, rococo parade, 2018), and other tools (Ricket blus, 2019). Despite concerning the body and therefore being potentially activatable, these objects take these identities onto their surfaces, questioning the body’s, its finitude (where does the body truly end?). Figures joined together in sexual acts or in collective experiences are paraded across these sculptures. Simultaneously, the work focuses on the possible visualizations of zero corporeality in a state of physical dispersion that creates proximity with other organisms. ANIMA, 2020, summarized this search. The identity depicted is divided into groups of elongated sculptures, like oversized worms while spoken narration makes room for rethinking categories and norms and drawings are charged with revealing the body’s prospect of inhabiting several lives (the installation is accompanied by a track in which a voice whispers stories, holes left open by the wallpaper on the walls, host small drawings of transitions and connections between bodies).

The theme of the multiple lives a soul may have gone through is also the subject of Il portico, 2020. Further deconstruction of the static and finite idea of identity is implemented, thanks to song and poetry. Under a portico, a group of performers intones poems rearranged as folk music that talks about ancient places through which the artist’s soul has passed.

Stultifera is presented as a synthesis of the artist’s last six years of research. The title, “dei folli”, returns us to one of the first elements identified: an interest in the pre-logical dimensions of thought. The work becomes almost a celebration of instinct, intuition, spontaneous planning, and the primordial forms of association between human beings. The “fool” is seen as antagonistic to systems that, since ancient times, have removed, silenced, and eliminated those considered different from the categories and criteria of normality. Here, the fool returns to the center by imagining a group of resilient vagabonds left to sail on the open sea, having been rejected by their homeland. However, this rejection has enabled them to question old customs and establish new rules for coexistence.

The drawing in Stultifera is further developed by being expanded to sculpture. The choice to use simple materials, assembly methods (through ropes, staples, wood, and knots), and, often, merely suggested shapes recalls the design aspect of the sketch, the freedom of execution, the spontaneity of the line, and its fluidity in correspondence with the thought of the person creating it.

The anthropological study of visual sources and other beliefs is transformed into a complex artistic pastiche. The artist created a work that results from assembling and revising past literary works (Sebastian Brandt’s The Ship of Fools, first of all), film clips (the entry movements of the choir revive the opening scene in Béla Taar’s Werkmeister Harmonies; others recall Vera Chytilová’s film Daisies), references to folk music and improvisational jazz, medieval court and amateur dance, propitiatory dances, lamentations and sacrifices, and finally to happenings and body art (the battle scene is a reconstruction of Carolee Scheenman’s Meat Joy). These fragments are reassembled in a sculptural-like process, including references to Benni Bosetto’s own art. One example is the scene in a hut where a group of performers has created a series of clay artifacts referring to the series of organic sculptures mentioned above.

This pastiche was edited using the formal contrast between visions of order and canon and irreverent and disgusting actions where the latter can introduce processes that give new meaning (the fool’s viewpoint reverses the vision), leading the audience to consider the arbitrariness of precise stylistic codes.

The human body is at the heart of the work once again, extended in communion with the organic and inorganic world around it. The ship in Stultifera appears to mimic the marine environment, its sails recalling a fish’s scaly skin. Fish return drawn on fabrics, and their movements are imitated in several of the work’s scenes.

The processes of dematerialization, often used by Bosetto find room in the voice-over, The Pause, a figure so ancient that she has lost the weight of her body. Her words are poetry, not logical thought. Once again, they tell of other beings and ecosystems: flowers, snails, butterflies, and seawater seem to be the references through which to rethink human origin.

Stultifera portrays the image of a human being embracing madness and bringing to light its tragic and cosmic nature, finding in the rituality of shared tears or the sound of laughter some of the liminal experiences from which to reconstruct human identities. The human being in Stultifera is never alone, showing its multiple nature from the first song (We Three—My Echo, My Shadow, and Me), up to the final scene in which the work invites us to rethink ourselves as a complex collective body, human and non-human, the essential social condition from which to build future coexistence.