No Question, No Prompt

Michèle Graf & Selina Grüter’s “Silver Star” at Halle Für Kunst Lüneburg e.V.

With works by Michèle Graf and Selina Grüter and curated by Elisa R. Linn, the exhibition Silver Star was characterized by repetitive, rhythmic movements of seemingly “useless” kinetic objects, which demonstrate intricate craftsmanship and typically proceed smoothly without interruption.

Here, there should first be a little information about Lüneburg, but I realize that I’d rather dive straight into the rattling machines of Michèle Graf and Selina Grüter, in their installation at the Halle für Kunst (similar works were shown at Kevin Space in Vienna and at Fanta in Milan). Although defined by their location, in the specific auditory nature of the space, the size and dimensions of the machines when seen as one image appear larger and distinctly more sculptural. They might even become something like a body, but onsite, they are more about function, and they are, of course, exactly as big as they are—roughly mouse-sized. (This is reminiscent of Kafka, who once linked the small with the uncanny—a little pig burrowing its way out of the floor.)

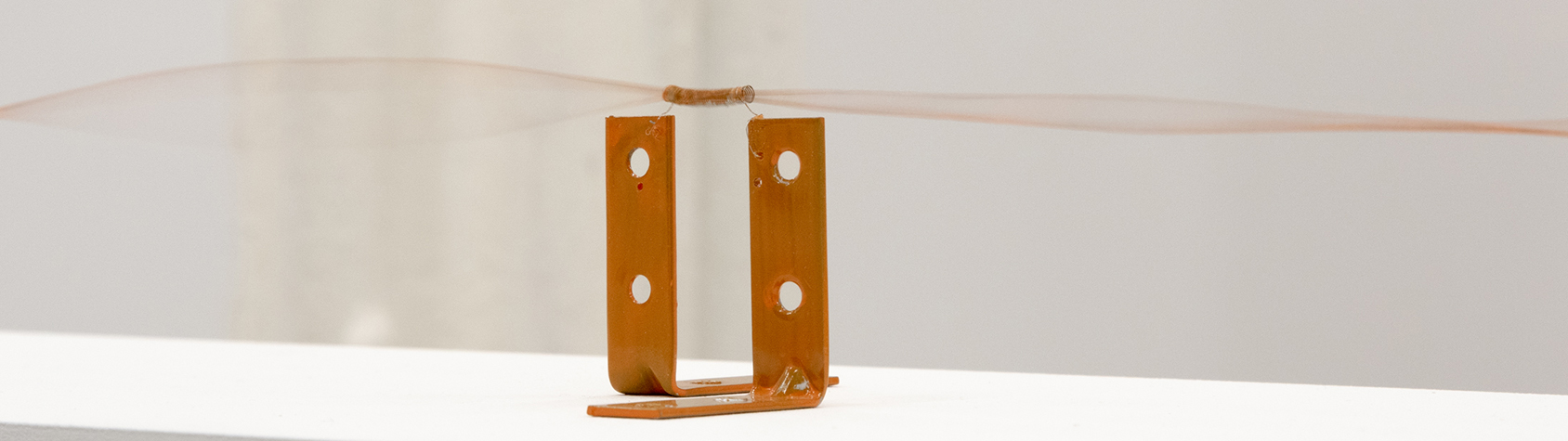

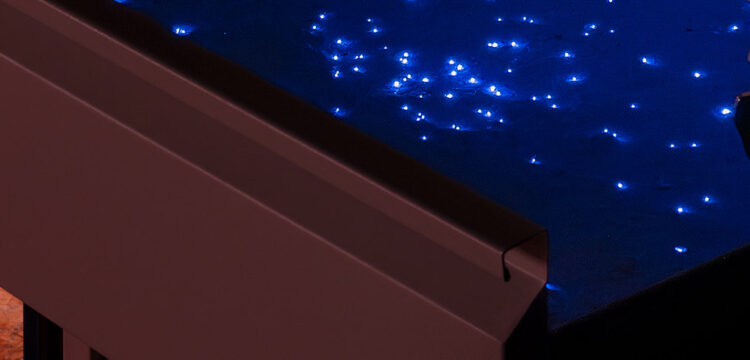

At the Halle für Kunst in Lüneburg, almost always, two parts of a machine correspond with each other over a long distance, connected by wires and strings. These can stretch across the space for up to four or five meters. Such taut lines usually define our airspace—ever since the invention of the telegraph by Samuel Morse, who never intended to be an inventor but actually wanted to become famous as a painter. The wires and strings hanging in the landscape—admittedly, from a subjective perspective—seem somehow melancholic and silent. That they power almost everything that enables our movement is not visible to the eye. They are dangerous, everyone knows it. But it is hard to see.

The clock strings, utility wires, and fishing lines here are in motion, engaged in the simplest mechanical movements—back and forth, turning on themselves, oscillating, or moving up and down, driven by the machines. Each arrangement of motor, counterpart, linear connecting element, and hidden drive and control mechanism is nevertheless a single machine. The exhibited, performing strand is internal, not a connection to another unit. I assume they are controlled via relays. The machine could function analogously but might also be programmed, incorporating digital elements and translating them back into the analogue. In previous exhibitions by Graf/Grüter, the machines were responsive, setting themselves in motion when an external sensor detected movement.

But in the exhibition space, the “how” hardly matters, as a certain sense of joy immediately sets in—joy over these tirelessly working machines. It seems to hint at the vision of the future of machines, as conveyed by Marx: that they would, so to speak, work on their own, while humans would sing and engage in all the other things they could otherwise do.

All the better, then, that they don’t do anything particularly useful. They don’t fold paper, drill holes, transport cameras, transmit sound, or perform symbolically charged instructions. Apart from leaving small traces of dirt on their pedestals—because, like so many sculptures, they have pedestals—they produce nothing but themselves. They aren’t even engaged with one another but operate in a completely self-contained manner. And one can’t help but think: if this is what machines do, there’s still plenty left for us to do. There is, then, a joy in the fact that they work—and, moreover, that they wait for nothing. No question, no prompt, just electricity. Then off they go. (In both of these aspects, by the way, in stark contrast to the currently more observed machines of Artificial Intelligence.)

When engaging with the work of the long-time collaborators and now New York-based artists Michèle Graf and Selina Grüter, one initially attempts to understand them—based on their earlier works with formal performances and similarly, receipt cut-ups in the classic ransom note aesthetic—not as discourses, but rather as a kind of reduction from language into sign.

They come into being—because that is the essence of any collaboration—always through a kind of back-and-forth, where something loose is transformed into an image by another person, then verbalized again, only to be left to the process for a while, observed from an external position by both, in its own expression. Something emerges in-between. This is the so-called “third element” of collaboration, which actually makes working as a duo impossible, because it always immediately appears. Almost everything one creates as art eventually places itself in front of the maker, but in collaboration, this aspect feels less uncanny. In this case, it even seems like something truly externalized, something removed from oneself. In a sci-fi drug thriller, it could be the externalized heart—suddenly spat out and cheerfully continuing to function right there in front of you, outside of yourself.

This exhibition at Halle für Kunst Lüneburg was curated by Elisa R. Linn and is yet another of the remarkable exhibitions which have taken place here in this institution, which originates from an academic context and, like much of the university sphere, has the appearance of a research facility that primarily communicates with itself and academic networks. Rather than resembling a local art association in the tradition of a Kunstverein, the exhibitions often feel like research reports on the state of contemporary art. The openings resemble collegial gatherings, perhaps even retirement celebrations. In this particular exhibition, the appeal of a technical museum is also present—one that, in terms of visitor satisfaction, has long surpassed art museums. Then, memories of kinetic sculptures and the immediate joy they brought to one as a child. Yet this is returned via the realm of drawing through the line of the wire, the black-on-white. I liked—and one can never know whether one is giving voice to a human constant or merely speaking about oneself—the idea that machines work for us, and I wouldn’t mind if painting and drawing machines were developed. These machines here are actually better in that regard because they remove the sense of purpose (drawing/painting/doing laundry) from the machine. In doing so, they reveal the essentially simple function of the new machines—those that draw, paint, or go by names like StyleGAN or otherwise: to merely switch back and forth between on and off, between 0 and 1.