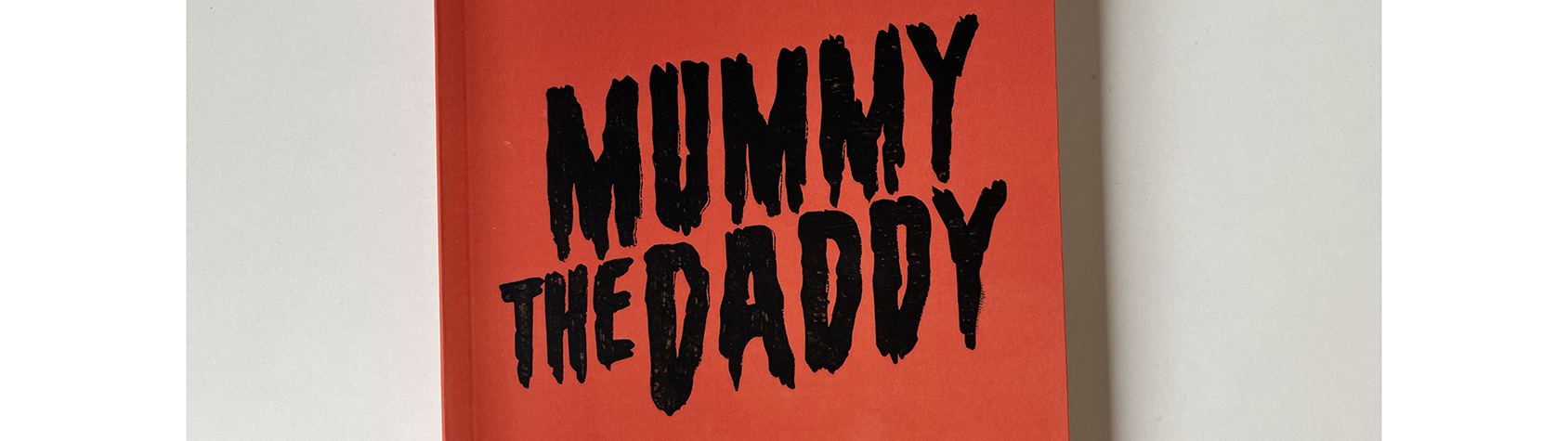

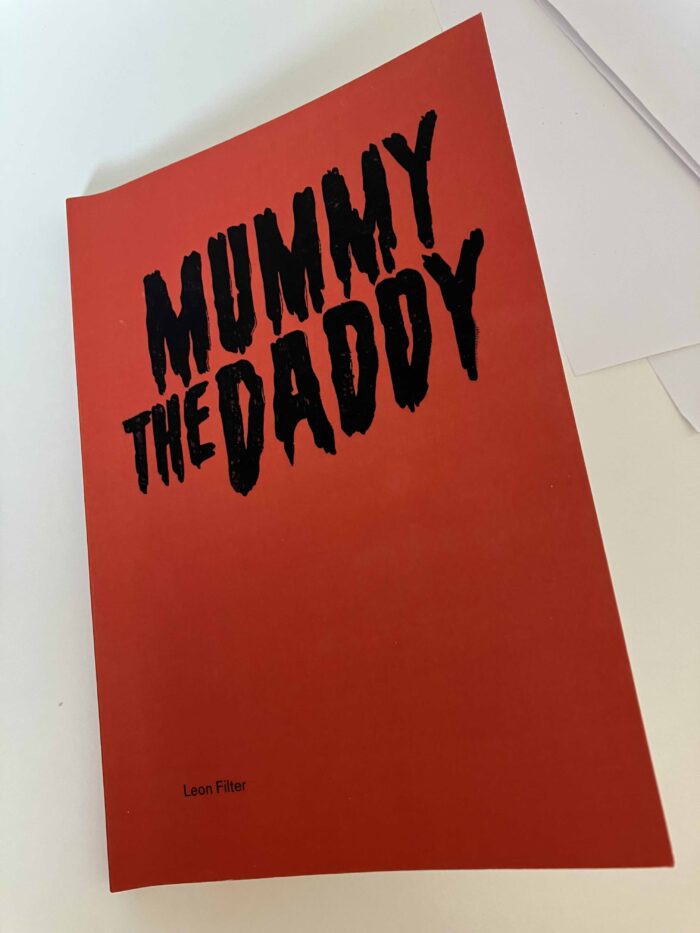

Mummy and Daddy

On Leon Filter’s artist book “MUMMYTHEDADDY”

Leon Filter’s artist book MUMMYTHEDADDY (Edition Malade, 2021) is a collection of personal anecdotes and written images that explore paternal relationships, inherited memories and experiences with familiar roles. Through stories of military service, dementia, and monsters, the author reflects on the complexities of family histories. By examining how we remember and forget, MUMMYTHEDADDY emphasizes the contributions of narratives in shaping our understanding of how intergenerational dynamics form, and proposes to reshape roles within dependency relationships.

In this constellation of debate and support among friends, Leon would like to acknowledge Valentina Curandi’s (afterwords) and Ian Clewe’s (design) significant contributions to the publication.

There are several reasons why Leon Filter’s MUMMYTHEDADDY made me want to write. The decision was taken because as I was reading through I already began to write in my head—mainly I believe, because of affective proximity. A parental figure is par excellence the one we look at with no distance, precisely due to this bond, we even tend to assume how they look—for us they will never be just-another-person-in-this-world. Yet the father is a complicated one, especially a father of the generation Leon speaks of, he sits uncomfortably over a role that does not suit him any longer. Again because we speak of a father, as if it would be my father, I can just assume. Obviously there are an infinite variety of stories, that is why Leon begins from his own—and that is why I attempt to recount such a book by keeping the most subjective tone. While reading, I began writing about a book written by a friend. Now that I am actually writing I feel I haven’t been writing for a while, so bear with me. In fact, I got this book right after I myself became a mother, so, a son speaking so candidly about his father many years after had me giggle more than once. I still think I would have nonetheless felt the whole matter as poignant. Among friends, a father often is a recurrent conversational subject, sometimes an elephant in the room and sometimes a bonfire.

“After the movie, my father, very delighted, told me that tonight, when I am lying in my bed, opening my eyes, there will be the mummy hanging over my bed, staring at me silently.

I still have nightmares about this one.”

Cinema

Coming out in the title, in this little artist’s book the mummy is meant as a cinematic subject. Indeed the first thing that happens is that we are sitting in a movie theater and the reel is about to start. Immediately after we are already peeping into somebody’s life: the tone is well-staged and witty, as what is unfolding is not an autobiography at large, but a specific relationship. There are three characters in this story: the voice of the speaking I, the anecdotes of and about—indeed—the father, and the mummy as a genre and a haunting presence, but also a recurrent very good pun.

“What I think he was telling me with these two stories is:

He will eventually be gone, but images stay*

*whether you want them to or not.”

Images

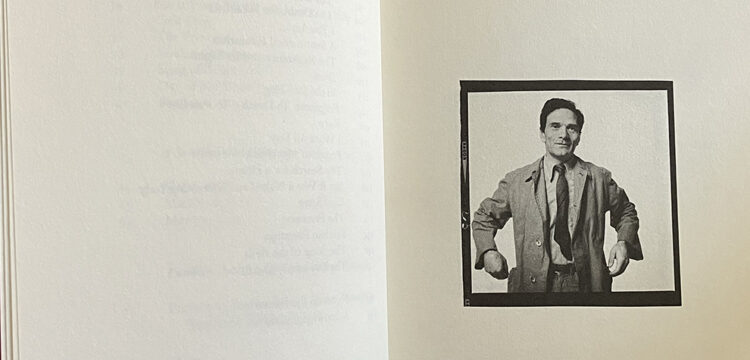

The actual images are absent. Faithful to the object that beholds the story the images are just captions—written snapshots of a memory, indeed images for the reader to imagine, although they still occupy a full page—as if. Those too are taken (like photographs) or made (like drawings) by the author. Ah, to insist on the multimediatic and layered nature of this work, it’s the right moment to tell that the first time I witnessed this story it was in the form of a performance, which had me laugh quite loud, I can still recall. This to say that before it becomes a thing, matter floats, lives and settles several times. So do our personal stories, so do we.

“The movie ends with the implication that idealized images and narratives—like smooth statues or written text—are worth conserving. At the same time, emotions need to be buried because they become distorted over time”

Implications

The figure of the father always comes with implications, it is a sort of droste effect, where inside a father there’re at least four other fathers with a more or less recursive legacy. Each generation is exposed to their own history they each have to react to. Who knows for how long the implications are carried around, what do we get to witness as children, and how sons become fathers—if they ever do. But mainly what’s of us when we are at the end of this lineage? If we (n)ever comply. It could happen we find ourselves sitting uncomfortably with the consequences of a generation. Again it all layers up in the strata of what we become.

“A few years back, I printed an image of Boris Karloff’s depiction of the not-yet-resurrected, sleeping mummy from the 1932 movie on a t-shirt that I later wore while visiting my parents. My mother, puzzled, instantly asked why I was wearing a shirt with my father’s face on it.”

Sentiments

Unlike the father, a mummy carries a dead body around which totally lacks emotions or memories—or, as in the case of the cinematic mummy, it obsesses over the same one. Like the mummy, the father has a precise role, which is quite difficult to get rid of—and he is often known for making of his sentiments a real exquisite corpse, or a combination of images assembled by seeing only the end of what the previous person contributed. The result is most of the time a surrealist pastiche, in which the “idealized paternal figure” is just a label—there’s no such a thing, Leon knows and we all know. A role is the costume one puts on to hide sentiments behind.

“The movie ends with the implication that idealized images and narratives—like smooth statues or written texts—are worth conserving. At the same time, emotions need to be buried because they become distorted over time.”

Anecdotes

Leon’s book is full of brilliantly told anecdotes. Obviously I can’t spoil any of them, but what I can say is that each of them is bringing intuitions—rather than conclusions—on how we attend, how meaning is revealed and roles can shift. It all serves a purpose. Well, speaking of cadavre exquis, I have an anecdote too. Last time we played the game with my friends we had a good extensive laugh which lasted for not less than five hours. When we stopped, our jaws and our bellies were hurting and it felt a bit like a transformative experience. Laughter literally buried us all, and we came out full of sentiments for each other. Anecdotes are affective images we take with us to gift to somebody else, and this little booklet, I find, is full of very precious treats.

“Eventually I will be gone

But images stay”