Mobilizing Memory

Rebel Archives: Logbook of an Exhibition

The archive can be a site of discovery, a space to trace origins and corroborate histories. Often perceived as neutral, the archive is also a place where history and collective memory are canonized. The artists featured in the exhibition rebel against a singular vision of what such histories may be. Curated by Sofia Gotti at Villa Era, Rebel Archives addresses debates within feminisms and decolonization that seek to reconfigure what/who mainstream culture should represent.

The exhibition Rebel Archives gives shape to a dialogue between my research and the work of Mendes Wood DM, focused on disruptive artistic practices of artists, who mobilized memory via the archive to generate new spaces of representation. The project brings together pioneering Afro-Brazilian artist Rosana Paulino (shown in italy for the first time) and the 1960s avant-garde icon Anna Bella Geiger alongside protagonists of Italian feminist militancy Clemen Parrocchetti and Nedda Guidi. The show also features Mirella Bentivoglio, amongst the best known in the group, for her life’s mission to bring women’s art to broad audiences. Both this text and the exhibition it accompanies are concerned with the network of people and past projects determined to expand the borders of culture.

Rebel Archives is an expression originally used by Marco Scotini to retrace the steps of feminist art in Italy, a narrative that is still largely forgotten in mainstream art histories. Of course, the widespread marginalization and systematic erasure of women artists internationally is well known. Less known is that, frequently, testimony of their activities remain held in private spaces; these “rebel archives” are now beginning to break loose. Within this framework such personal archives become alternative spaces of representation that create a new way for art to endure outside the market and institutional dynamics.

The archive has been a contested category in contemporary art particularly since Michel Foucault, along with his Parisian post-structuralist peers, started interrogating the formation of knowledge and, by extension, culture. Foucault’s enquiry related to the discursive rules that govern the epistemes of knowledge from the Renaissance to Modernity, which are regulated and preserved within archives. For Foucault the archive is “the system of discursivity” that establishes the possibility of what can be said. Foucault’s view was criticized by Judith Butler, who highlighted how the thinker’s appraisal of the archive omitted the gendered body. She questioned whether culture can be solely contained within language, or if there is something that eludes this system of signification. Alongside such philosophical debates, a plethora of artistic practices have adopted the archive as their subject matter, seeking to question the validity of cultural knowledge handed to them. As Hal Foster astutely observed, “might archival art emerge out of a similar sense of a failure in cultural memory, of a default in productive traditions?”

Such questions bring forth a dilemma, particularly pronounced in the context of 1970s Italian Feminism. An artist who is willing to participate in the market system has to accept to a great extent its rules. Subsequently, they inevitably comply to capitalist patriarchal power structures that stand in opposition to core feminist beliefs. What to do: be an artist within this knowledge system, or a feminist who rejects patriarchal norms? [1] In this context, the personal archive acquires new relevance as a site that thrives outside of patriarchal systems of power. By existing on the margins of the market and institutions, personal archives are alternative cultural formations that resist a patriarchal economy of representation and institutionalization. Aware of the complicity of a gallery exhibition with capitalist market systems, this text aims to reveal the shared stories and collective efforts that have been committed to shining light on the artists featured in Rebel Archives (as well as a multitude beyond them). This writing functions as a logbook: on the one hand some of the key works and trajectories within the show are explained; on the other, I discuss the personal stories and connections that allowed this project to exist.

The first artist encountered in the exhibition is Rosana Paulino (São Paulo, 1967, where she lives and works), whose work I learnt about thanks to Mendes Wood DM’s research. Paulino’s extraordinary practice emerged in a context where institutions were wholly unreceptive to her as a black female artist. The cultural traditions she was surrounded by as both a student and a teacher only represented her body as savage, subaltern, laboring, nursing. Her work builds an epistemology of blackness in Brazil—a country where 55% of the population is non-white. She addresses the objectification of the black female body and its historically eroticized and colonial representations. Documentation is central to her work; she often employs it to subvert the cultural associations of the images she selects. The sown fabric collage of photographs and drawings titled Musa Paradisiaca (2020) introduces some of the broader themes of Paulino’s practice. The artist refers to her stitches as “sutures” to convey the memories of violence embodied by her subject matter. The work’s title is the botanical binomial nomenclature for a common banana. Using this term, Paulino plays with its stereotypical associations to the muse and the Garden of Eden, thereby critiquing structures of bio-capitalism and bio-colonialism in Brazil. The images used in the piece are botanical plates, animal x-rays and photographs drawn from postcards made for European audiences from the end of the XIX century, intended to portray Brazil as a wild and exotic place. Printed in blood-red letters, the words “Yes, nós temos” (Yes, we have it) refer to a popular carnival song from the 1920s about the exploitative export of natural resources from Brazil. In appropriating these lyrics, Paulino critiques the current Brazilian government’s policies incentivizing deforestation and extractivism.

The dissident and denunciatory vein present in Paulino’s oeuvre, shares ground with Clemen Parrocchetti (Milan, 1923–2016), who actively fought to secure basic rights for women, protesting for divorce bills and abortion laws. The exhibition features work by Parrocchetti that uses domestic objects associated with female chores, such as sewing tools and nursing instruments, as well as stuffed truncated female body parts or crevices resembling lips or vaginas and inverted cones. Such applications in her assemblages and work in textiles play on stereotyped notions of femininity and the domestic and denounce the objectification of the female body. One of the major works by Parrocchetti we were able to display at Villa Era, is the brown jute tapestry Scream Towards Hope (1978), which was originally shown at the 1978 Venice Biennale. On that occasion, the exhibition was organized by the feminist collective Immagine from Varese, a group Parrocchetti was part of for several years. The tapestry was displayed hanging from the ceiling alongside other works by members of the collective, as to envelop the viewer in an immersive environment. This piece in particular, had been exhibited in 2019 at the exhibition curated by Marco Scotini and Raffaella Perna, The Unexpected Subject: 1978 Art and Feminism in Italy (FM Centre for Contemporary Art, 2019). In the weeks leading up to its opening, I was introduced to Clemen’s work and her archive, curated by Caterina Iaquinta, held in a medieval castle in Borgo Adorno (Alessandria), a house museum open to the public. While Parrocchetti never had a permanent gallery to represent her, her astonishing exhibition history proves her presence in the public eye throughout her life, but her resistance to engage in market circuits.

A similar trajectory is shared by Anna Bella Geiger (Rio de Janeiro, 1933, where she lives and works), who never had a gallery until she chose to collaborate with Mendes Wood DM, although she succeeded in placing her works in public collections internationally alone. Geiger also shares with Parrocchetti a concern with the female body and its role in the formation of identity. This is key within Geiger’s “visceral phase” (1965–1969), a definition coined by critic Mário Pedrosa, which features prominently in the display. Working against the dominant trends of the period when geometric abstraction dominated avant-gardist experimentalism in Brazil, the artist made watercolors and etchings of internal female and male organs (at times sexual). In these works, Geiger interrogates the bodily and the corporeal searching for ways to engage the participation and physical reactions. In works such as Meat on the Board (1968), the flesh becomes cartographic through the appearance of a map of the Southern Cone, a common trope in Geiger’s oeuvre, which is further explored in the exhibition.

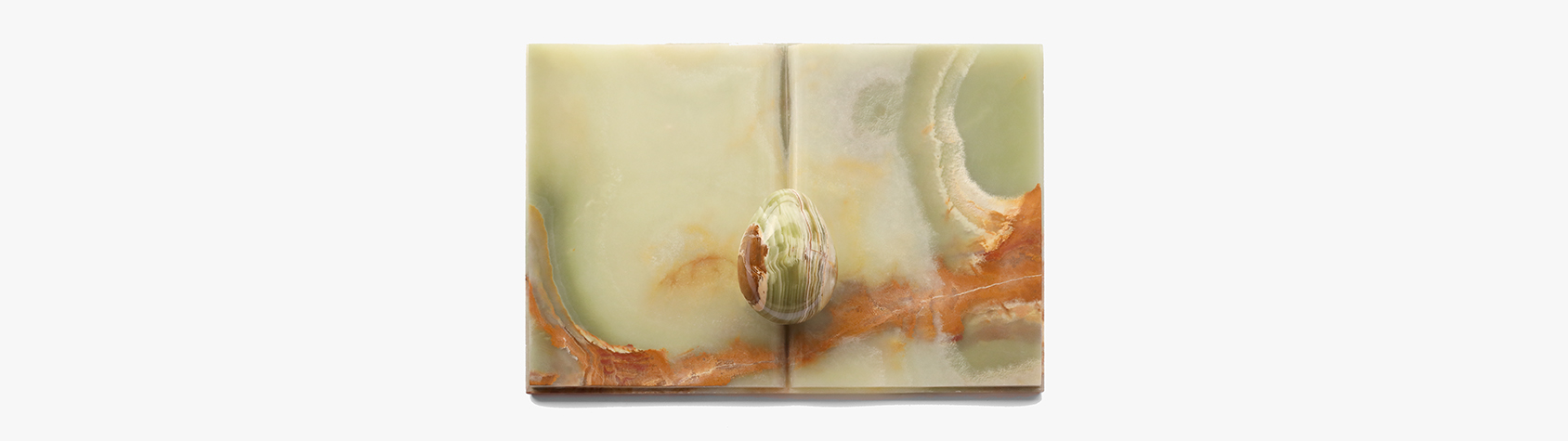

Adjacent to Anna Bella’s room we encounter Mirella Bentivoglio (Klagenfurt, 1922–Rome, 2017) who similarly pursued a correlation between the visual and the bodily throughout her practice. Starting her artistic trajectory in Visual Poetry, Bentivoglio found in the letter “O” the materialization of this connection. “O” in Italian a conjunction meaning “or”, which also calls forth the other, the alternative. The artist soon transformed this vowel into an egg, a symbol of circularity, origin, femininity and life, which guided her later enquiries into the relationship between nature and culture. In the seminal work Goodbye Trees (1970), the letters composing the word “Addio” [Goodbye] are themselves images of trees. Bentivoglio points at how integral plants and trees are to our knowledge systems (they are our alphabet!), yet she simultaneously warns about the dangers of treating them merely as a disposable resource. While Bentivoglio is amongst the best known artists in the exhibition, her practice is yet to be fully institutionalized—a task taken on by Mirella’s daughters and her close collaborator Paolo Cortese. Though her extensive archive is held at the MART in Rovereto (including 450 artworks and mail art by hundreds of artists), so much of her practice is yet to be explored and shown. Only recently galleries, such as Mendes Wood DM, Osart and Repetto have endeavored to reconstitute Bentivoglio’s presence on the market.

In the final room of the show is Nedda Guidi Gubbio, 1927–Rome, 2015): a militant feminist, co-founder of the Collettivo Beato Angelico in 1976, and close friend of Mirella. With a pervasive impulse to contest everything normative, when Guidi chose terracotta as her sole medium she did so against the grain. With Amphora (1989), for example, Guidi alters traditional techniques for making vases. Instead of using lathes or wheels to make rounded and sinuous vessels, Guidi chose to employ the much more challenging technique of casting, nodding to minimalist sculpture. Interestingly, another leitmotif of Guidi’s practice is the inverted triangle, prevalent in Parrocchetti’s oeuvre. This is visible in several of the works shown in the exhibition, from Object Sculpture, a 30kg block of enameled terracotta, to the At the Origin of the Sign (1982) where the titular origin symbol is a terracotta triangle on the sculpture’s surface. The latter work is a homage to the Ebla Clay Tablets, amongst the oldest examples of cuneiform script (Sumerian and Eblaite) to be recovered, dating back to the third millennium BC. Using different colorings, Guidi establishes a connection between earth tones and Ebla’s language.

I found out about Guidi in the archives of the State University of Milan, as I was researching the Collettivo Beato Angelico. There I discovered copious mentions of her name; suddenly, an extraordinary amount of material, books, catalogues, invitations to biennials and exhibitions exploded from right under me. I was astonished by her oeuvre and couldn’t fathom why I had never heard of her, despite being deeply familiar with the work of her peer and friend Leoncillo and Lucio Fontana’s experimentation with ceramics. Further research led to the name of Riccardo Boni, the right arm of the late quintessential Roman art dealer Enzo Mazzarella, who worked with Nedda for decades. Alongside her heirs, Riccardo is the custodian of her work, which is bursting out of the confines of her studio (until recently infested by violin spiders, one of the very few venomous spiders in Italy harmful to humans).

While it is clear that the artists on show share little formal resemblance, there are several of shared trajectories in their practices, from a concern for ecology and sustainability ante litteram, an exploration of sexuality and bodily experience, an urgency to construct new visual epistemologies. It is finally vital to stress, that this project builds on the work of a multitude of initiatives devoted to setting rebel archives loose. Notable examples are the aforementioned The Unexpected Subject, as well as Paola Ugolini’s Body to Body at the Galleria Nazionale D’Arte Moderna in 2017, and more recently the extraordinary unearthing of works by Lydia Silvestrini or Lisetta Carmi at the latest Quadriennale di Roma (infinitely more would deserve to be mentioned).

As Scotini writes, “what is at stake is not just the opening of the rebel archives of our past […it is] on the one hand the breaking of gender binaries, and on the other the decentering of the human…”. The central question relates to post-anthropocentric perspectives, to subjectivities that are Other to the normative (white, male heterosexual), and how these strive for a space of representation within culture. This questioning extends as far as to include Nature, which Donna Haraway notes as “[excruciatingly constituted] as Other in the histories of colonialism, racism, sexism and class domination of many kinds.” The repercussions of this process of retrieval are all-encompassing.

[1] This was the choice Carla Accardi had to make when compelled to take distance from feminist collectives because of her necessity to also be part of the art world – something her close friend and essential feminist theorist Carla Lonzi could not accept, and that precipitated the end of their friendship. I wrote about the Lonzi/Accardi schism in “The Art vs. Politics Conundrum: The Case of Carla Accardi and Carla Lonzi, 1963-1973,” in Contra o cânone: Arte, feminismo(s) e ativismos séculos XVIII a XXI,

Seminário Internacional 12 Bienal do Mercosul, 2020, pp. 183-190. See also: Francesco Ventrella, “Carla Lonzi’s artwriting and the resonance of separatism”, European Journal of Women’s Studies, 2014, pp. 282-287; Laura Iamurri, ‘“Un mestiere fasullo”: note su Autoritratto di Carla Lonzi’ (‘A phoney profession’: Notes on Autoritratto by Carla Lonzi), in M. A. Trasforini (ed.), Donne d’arte. Storie e generazioni (Women of Art: Histories and Generations), Roma: Meltemi, 2006.