Matters of Perspective

A history of environments

The second chapter of the exhibition Inside Other Spaces. Environments by Women Artists 1956—1976 at Haus der Kunst in Munich looks at Zaha Hadid’s MAXXI as the main envelope of the other environments on display and extends the research to 2010, the year the museum opened. Ambienti 1956-2010. Environments by Women Artists II at MAXXI in Rome is on view until 20 October 2024.

This is an history of environments that differs from the one we know from art history books.

It is about an art form that has its roots in the first half of the 20th century, not only in the lifelong work Merzbau by Kurt Schwitters (1923-1937) and in the experimental displays of the Surrealists and Dadaists, but also in the aims of the Futurists and in the environmental extensions of the De Stijl movement. Environments were firstly well understood by architects and designers, who immediately welcomed epigonal examples such as those in Italy by Lucio Fontana (his first “ambiente” dates back to 1949) and Nanda Vigo (her display for a Fontana exhibition dates from 1962 and her collaboration with him for the two spatial environments for the 13th Milan Triennale was in 1964; one of the two, Ambiente spaziale: “Utopie”, was reconstructed in 2017 and can be seen at MAXXI).

It is an history that then took shape, focusing mainly on its origins in North America and on its best-known voice, Allan Kaprow, who used the term “environment” as a translation of Fontana’s “ambiente” and not the other way around, and almost ignoring the South American scene and many European contributions. Since environments are places that need to be inhabited and perceived, and are not only difficult to institutionalise but also to commercialise, this history became a victim in being seen in one direction.

To really see things, you have to immerse yourself in them, you have to dedicate time and space to them, you have to concentrate first and then distance yourself so that facts can speak for themselves. This is what happened to Andrea Lissoni, the artistic director of the Haus der Kunst in Munich, and Marina Pugliese, an expert in the field of environments, who—with the help of researchers, restorers, archive photos, amateur videos, seminars, study days, visual and bibliographical data—managed in three years to lay the foundations for a different history and break away from a predominantly North American and male-centred view.

The results were exhibited in Munich under the title “Inside Other Spaces. Environments by Women Artists 1956-1976”, where twelve environments were carefully (almost archaeologically) brought back to life. The exhibition began with the year 1956, the date of the first environmental project by a woman artist, Tsuruko Yamazaki, with her Red (Shape of Mosquito Net), which was first exhibited for the “Outdoor Gutai Exhibition” in a park in Ashiya, not far from Osaka, and ended in 1976, when Germano Celant’s “Ambiente/Arte” opened at the 37th Venice Biennale. An event that played a significant role in the history of environments and for which the Central Pavilion at the Giardini was stripped of any additional structure, marking an interesting parallel to the recent orientation of MAXXI.

Here, Francesco Stocchi, together with Lissoni and Pugliese, has curated an exhibition that not only brings in Rome ten of the twelve environments showed in Munich, but also takes a different approach, inspired by one of the most controversial architectures on the Italian museum scene. “Ambienti 1956-2010. Environments by Women Artists II” occupies the entire first floor and offers a unique opportunity to revitalise the space. This approach of starting almost from scratch resonates with the historical Celant’s exhibition and emphasises on how Zaha Hadid wanted both visitors and artists to interact with her space. By removing all remnants of past exhibitions, the museum itself has become a vast, fluid environment in which a fruitful and open dialogue has been initiated through the eighteen environments displayed in line with Hadid’s structure. This is particularly evident in the artists featured in this Roman second chapter of the exhibition, whose works adapt to the skin of the Iraqi-British architect.

Pipilotti Rist is showing her first installation work in which she has switched from monitor to video projection (Sip My Ocean, 1996). The mirrored double projection in one corner follows Hadid’s walls, which are not straight at all, giving the viewer a sense of vertigo, in addition to the unease evoked by her reinterpretation of Chris Isaak’s song Wicked Game, in which scratchy, almost shouted interruptions transform the dreamlike underwater vision into a somewhat grotesque experience. Kimsooja opted instead for a delicate but effective intervention, choosing a special corridor suspended like a bridge from which the exterior of the architecture can be seen through the windows. Here, a special version of To Breath (2006-2024) by the Korean artist with square diffraction films on the windows gives the viewer the opportunity to experience the space in a colourful, diffracted and almost blurred way. This encounter takes place after being in environments that can trigger a state of distress, such as: the powerful We used to know (1970-2023) by Tania Mouraud in which the noise emanating from the totemic metal sculpture, together with the high heat and strong light, can only be experienced in a zen-like state of consciousness; the apparent danger in Micol Assaël’s Sleeplessness (2003) where suddenly it seems to find oneself in a kind of building site; the blackness and windy space of Laura Grisi’s from her series Natural Elements (1968); the experience of “Penetration, Ovulation, Germination, Expulsion” in A casa é o corpo by Lygia Clark (1968).

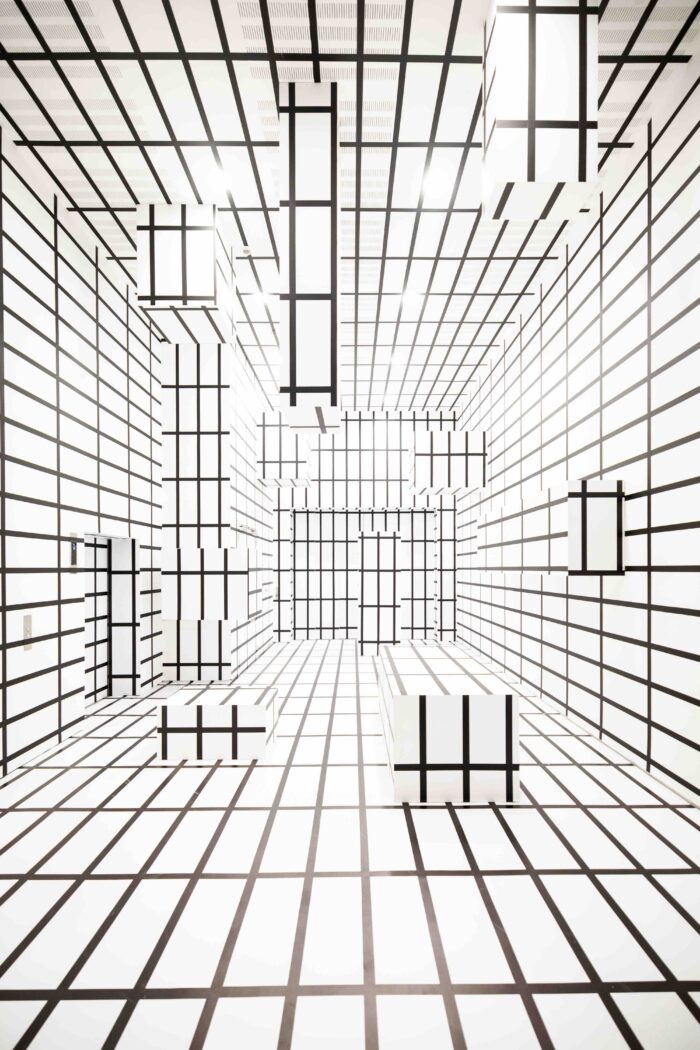

The world is by no means as tangible as the invention and application of linear perspective would have us believe, as Esther Stocker’s black-on-white grid so clearly reveals in her first environmental work from 2004,“Das Wort ,gleichartig’ zieht unsere Aufmerksmkeit auf sich, und doch besagt es eigentlich gr nichts,” which was revisited in MAXXI and encompasses not only a room, but even the lift that takes the visitors into it. Her reference to the mechanical instruments used by Renaissance artists in “having a rule to imitate the truth” (Leon Battista Alberti, De pictura, 1435) becomes even more evident in her latest intervention, entitled Prospettiva, in Rome’s Vittorio Emanuele metro station. Allowing visitors to see the three-dimensional space divided into orthogonal lines is almost like touching the mechanical principles behind the West’s deep need to see the world in a certain way, governed by the illusion of stability and the absolute centrality of the human eye.

But reality is more like diffractions that encompass other spaces, illuminate shadows and bend the horizon, as the intersecting planes, shifting focal points and curved walls of Hadid’s Roman space show so well. And the vessel we need to navigate in this space is today probably more of an “etherotopia” par excellence, to quote Michel Foucault’s 1967 Of Other Spaces (published in 1984): “In civilisations without boats, dreams dry up, espionage takes the place of adventure, and the police take the place of pirates.”