Machines, Sex and Apocalypses

An interview with film director, visual artist, and writer Pedro Neves Marques

Tracing a common thread that connects colonialism and ecology, biology and technology, politics and sexuality, Pedro Neves Marques’ films and writings activate processes of hybridization among elements of reality that are usually considered disconnected from each other. In this way he multiplies the perspectives through which to tackle issues that are too often addressed from univocal points of view. Pedro Neves Marques recently took part to DEMO – Deptford Moving Image Festival and had a solo show at Gasworks in London titled It Bites Back.

Felice Moramarco: Colonialism and apocalypse usually constitute the scenarios in which your works unfold. Could you give us some coordinates to navigate this complex landscape and tell us how you developed it?

Pedro Neves Marques: Some years back I was happy to work with e-flux journal in editing a section of their Supercommunity issue, titled Apocalypsis. The challenge for me was to counter the Western perspectives on the end of the world, the apocalypse, or dystopia with other views and myths about endings, especially indigenous. From my perspective, the problem with current dystopian futures is how they remain teleological and messianic, rather than looking sideways for “othered” narratives.

The dystopias we mostly read and see do not depart from white people’s expectations of the future, be it on the side of anarcho-primitivism or tech-driven ingenuity. The irony here is that while indigenous peoples, for example, have actually lived inside such predetermined images of “apocalypse” for centuries, white people (or Modern or Western or whatever you may want to call it), when faced with their own self-induced meltdown, make those imaginaries their own image of decay. Put differently, white people have actually appropriated others’ ruins, as if through this “assimilation” they would erase colonial differences between them and all those they once brought down.

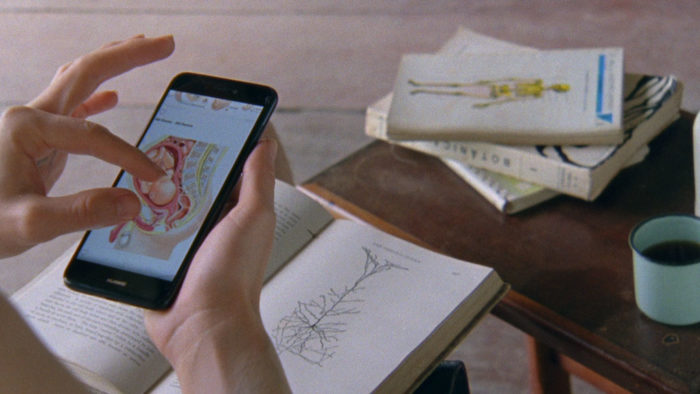

Pedro Neves Marques, A Mordida [The Bite], 20′, super 16mm transferred to digital video, 2018-19. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Umberto di Marino.

No, I’m not saying there isn’t a political potential in dystopian visions. I’m saying that there remains an anthropology of dystopian visions to be made. We must multiply perspectives. It is in this anthropology that I’m invested in, and from which most of my films and writings come from.

Pedro Neves Marques, Aedes aegypti, digital animation video, 1’50” loop, 2017. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Umberto di Marino.

In some of your films—I’m thinking about films like Semente Exterminadora and A Mordida—elements of science fiction mix with a more documentary approach. Is this functional to the “multiplication of perspectives” you have just mentioned?

Not necessarily. I take this idea of the multiplication of perspectives from Brazilian anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, to whom I am very indebted, but I would not dare illustrate or quote any such theory. But I do embody some of it and try to express and push it through storytelling and image-making. What I mean is to write and film with the notion that something that looks so and so to you, might, anthropologically speaking, be radically different from another’s point of view—even if that object plays similar roles in different worlds. There is a politics, and a queerness, to those liminal spaces which I’m trying to follow.

As for science fiction, I grew up reading it, so it’s only natural for me to pay my tribute these days. However, I’m interested in a science fiction that barely reads as such; something that reads as veritable and feels almost commonplace, be it in the way I write or film, or in certain locations. The world is weird enough as it is.

Pedro Neves Marque, Digital Animals: Dream Sequences, 20′, video, 2017. Produced by Stenar Projects. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Umberto di Marino.

In your critique of colonialism you seem to suggest that besides shaping the world through genocide and destruction of ecosystems, in order to control the biological reproduction of life itself, contemporary forms of colonialism intervene on sexuality as well.

Sexuality, both human and non-human, was always key to settler colonialism. Sexuality here means both the control of reproduction as well as the normatization of bodies and relations. From a capitalist standpoint, only certain strands of crops, certain animal hybrids, or certain types of “females” make sense. All of these were (and still are) produced for and through colonialism. So, you have to think this through holistically. That’s why I’ve borrowed from science fiction the term “terraformation” as for example in Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy: we’re talking about the manipulation of entire biomes.

Pedro Neves Marques, The Bite, 26′, super 16mm transferred to digital video, 2019. Distributed by Portugal Films – Portuguese Film Agency.

And do you think that the realities that emerge from these processes of “terraformation” are always completely subjected to colonialism or one could also find in them elements that escape its logic?

Yes, there are also novelties, in particular technologies, that have emerged from this cultural and scientific paradigm which can and are constantly being appropriated against the “system.” By this I don’t necessarily mean only those voluntary struggles against capitalist modes of reproduction, but also, at a more mundane level, how people live daily through this technological mess we have inherited and how creative we all are in such uses. Through my work, I hope I can answer to both this history of repression and divergent stories of survival.

Pedro Neves Marques, YWY, The Android, 7’40”, video, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Galleria Umberto di Marino.

An aspect linked to biological reproduction is of course eroticism which, in works like the series of poems Viral Poems, appears to be inherently political. In the 30s, Walter Benjamin famously stated that one of the ways to oppose the spread of fascism in Europe was to politicize art. Now, after almost a century, the rise of fascism is happening globally, employing even more pervasive means. Would you suggest that beside the politicization of art, the politicization of sexuality could now also be a way to oppose fascism?

Sex and sexuality is where many social tensions are sublimated. But also, historically, where they are resisted and played with. It is ridiculous to say that sexuality is a space from which to resist fascism, but at the same time, yes, from a LGBTQ+ standpoint it is a space against normatization. That’s why it is yet again so vehemently under attack.

What I mean by sexuality is a whole spectrum, from sex acts to gender identity to reproduction. And what I find in sexuality, making it so endlessly fascinating to me, is the coexistence of pleasure and conflict. At a linguistic level, it is also the confusion between the natural (biology) and the cultural (metaphor)—as in “fluidity” meaning both of gender and of bodily fluids.

I’ll briefly use two recent examples. One the one hand, the corporate branding of Pride; how it highlights the tension between political struggles and their recoding by capital, or between contentment with liberalism or rupturing biopolitical imaginations. On the other hand, I recently saw Kathy Acker’s retrospective at ICA London. Although I am influenced by her writings, I was struck by how out of time her politics felt to me. What I mean is how her rerouting of masculine violence against patriarchal masculinity, and submissive femininity, seem to have been recoded. How the pornography of her penetrative aesthetics has become commonplace, precisely because it stills relies on penetration (I mean it both literally and figuratively) as a violent act. In fact, it all felt segmented and rather lacking in fluidity and care.

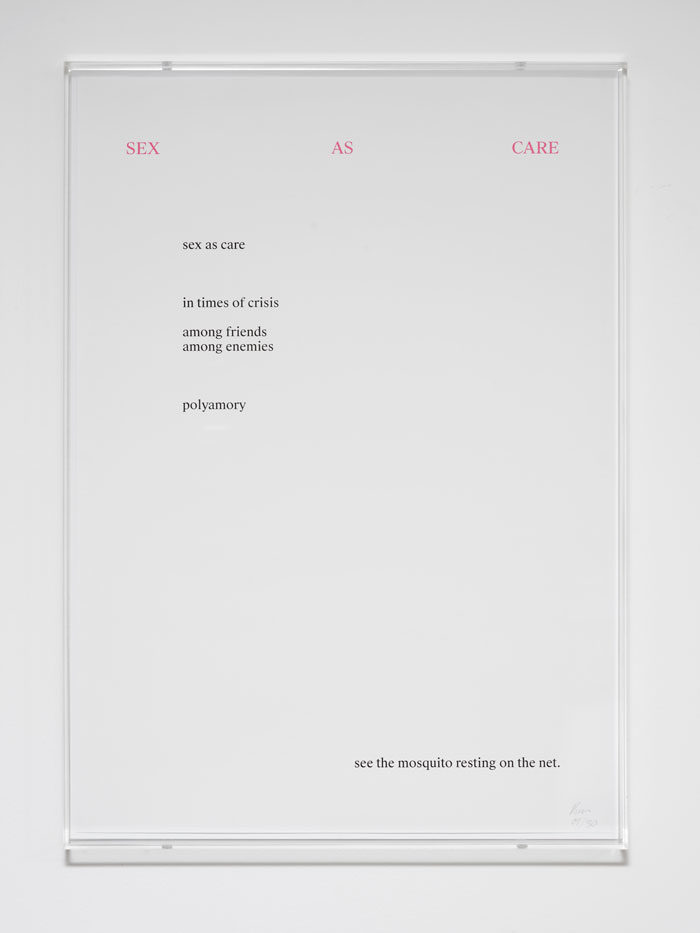

Pedro Neves Marques, Viral Poems, set of 21 poems, 60x42cm, digital print on cotton paper, acrylic frames. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Umberto di Marino.

Another recurrent element in your work is the uncanny relation between plants and robots—The Pudic Relation Between Machine and Plant and Exterminator Seed for instance. What do you think this relation can tell us about the current cultural configuration in which we live in?

True. Those films were made around the same time, and though they’re very different, there’s a clear link between that ambiguous scene (is it care or violence? is it sexual? is it a dance?) among a robotic hand and a sensitive plant in The Pudic Relation Between Machine and Plant and YWY, the native android woman in Exterminator Seed, which, together with the actress, Zahy Guajajara, I am still working on.

I feel the way robotics is imagined, especially in the West (as far as I know, it seems very different in East Asia), is quite revealing of “our” prejudices towards otherness. Androids are both less and more than human. They are regarded as simultaneously below and far above the human, as modernity conceives it (for obviously “the human” means something altogether different in Amazonia or in Japan).

Pedro Neves Marques, The Pudic Relation Between Machine and Plant, 2’30” loop, video, 2016. Courtesy the artist and Galleria Umberto di Marino.

Because we are still dealing with “hard” technologies, rather than with wetware robotics, it’s interesting to contrast it with the longstanding manipulation of the plant world. While the capitalist concern with plants stems from the control of reproduction (the extreme example is GMO seeds), it’s funny to look back at Karel Čapek’s 1921 theatre play R.U.R., which first proposed the word robot, or for that matter at John von Neumann’s self-replicating machines, and find that throughout the underlying fear is the reproduction of machines and AI. But what happens once these two worlds, of machines and plants, of robotics and biology, start talking to each other, and innovating on each other, regardless of humans?