Ljubljana in Four Acts

A reading of a city through the work of her artists

When the old world was still in place, at the down of this turbulent 2020, Paola Paleari was in Ljubljana for a month. Before the lockdown we agreed we would have published her report once she got back. Well, many things have happened meanwhile, despite this was only three months ago, we count on the fact that the whole world was on hold, and the reflections that stemmed from her visit and encounters gain an extra value from this delay between the lived and the written. The following is an account of her experience, narrated through meetings with Slovene artists Agnes Mormirski, Špela Petrič, Neja Tomšič and Sara Bezovšek.

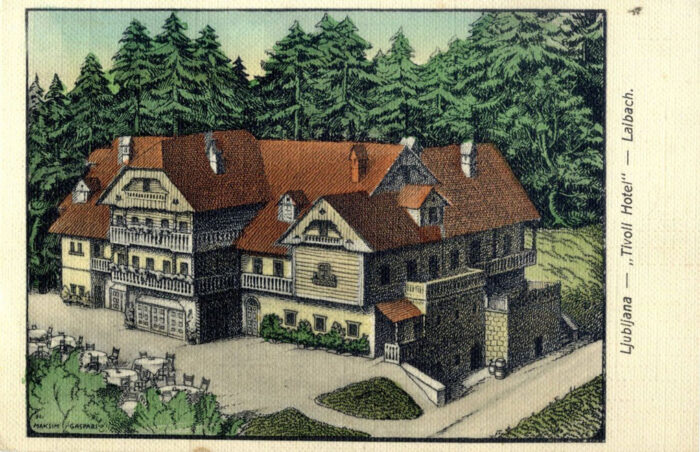

At my arrival in Ljubljana for my residency at MGLC Švicarija, darkness has already fallen. The taxi that picked me up at the airport swiftly moves out the city traffic, takes a wide but unpaved road uphill and stops at the foot of an imposing house. I can only see the edifice’s outline: a black shape against the shadow of trees behind it. The silence is deep, the air cold and the atmosphere half gloomy, half fairy: I am already in love with the place that will be my Slovene residence for one month.

With the morning light, I explore the surroundings and discover the manor’s gracious side. A former turn-of-the-century hotel, Švicarija (“The Swiss House“) owes its nickname to an Alpine-styled wooden guesthouse that previously occupied its place, in the heart of romantic Tivoli Park. In its roaring years, the bohemian elite used to gather there, and cultural life bloomed between its walls. At the end of WWII, after a few years of serving as social housing, a group of artists took the building over and settled their ateliers there. The Swiss House suffered from poor maintenance until a recent meticulous refurbishment returned it to its original splendor.

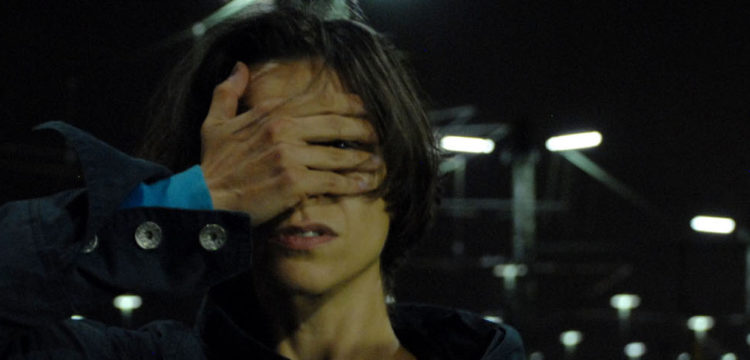

The suggestiveness reaches its peak in the evening, when the internal wooden staircase creaks under my feet as I go up to my apartment, and a reassuring calm pervades the corridors. Behind each door hides a creative habitat on its own, since many spaces—that originally were hotel rooms—are still used as artist studios. The fascination is such that I hear a hypnotic voice chanting what sounds like a mantra from the door next to my apartment. I’m not dreaming: it’s my fellow resident, Agnes Mormirski, practicing for the live performance part of her solo show siXren (Verbum Medicinae), scheduled at MGLC Švicarija in a few weeks.

“Name it. So be it, so it is” and “Words affect matter” are among the echoed formulas that soothe me to sleep every night, and that will come alive on the day of the performance in a matrix of contemporary noise music, techwear aesthetics, smell and light. The transformative powers of repeated verbal runes are a topic in the project, where Agnes wears the role of the mythological siren (half woman, half bird) showing the way towards the upcoming posthuman future. More generally, voice and language are central in Agnes’ practice, and instrumental to the exploration of the posthumanist scenarios that she presents in her videos, performances and spatial installations.

Due to its location at the crossroad between science, technology, philosophy and art, posthumanism is interdisciplinary by definition. In harmony with this is the fact that Agnes often collaborates with a team of creatives to implement her work. For siXren (Verbum Medicinae), sound artist beep blip composed the performance’s soundscape, while fashion designer Brina Vidic collaborated on the visual identity and the futuristic techwear costume design.

“As an idea maker, I create large cosmoses of meaning that encompass the audience on the sensorial, mental and emotional level. It would be overbearing of me to think that I can produce them by myself in all their many aspects and details,” says Agnes.

Beyond its practical aspect, working in teams is a source of intellectual nourishment. Together with writer Georgia Kareola, Agnes initiated Specter, an interdisciplinary platform that investigates human enhancement through offline and online curatorial interventions. The latest project, developed by Specter as part of The Wrong Biennale, is Cyber Sanctuaries: a digital spa environment where to relax and replenish by navigating through virtual hot springs and wellness rooms. Here Georgia and Agnes took the curator’s hat on, assigning each space to a different artist (or artist group) and closely collaborating with them in the realization of the digital ambiance. “As an individual, I have a limited viewpoint. To co-create provides me with a considerable benefit, that is, informing what I do with the perspective of the collective. The augmentation of my own self via the others is among the most interesting qualities of my artistic practice.”

MGLC Švicarija, Ljubljana, 2020

One of posthumanism’s foundational principles is that human nature is continuously shifting, both as a means of expression and a way of understanding. In this evolutionary journey towards an enhanced version of ourselves, technology plays a crucial role. Not so much in making us invincible or immortal, as in offering us the possibility to explore an expanded, more-than-human take on life. “We’re at a point in history where the epistemological categories we have been applying for centuries are collapsing. To think in terms of divides such as nature vs. culture, organic vs. inorganic doesn’t any longer reflect the symbolic structures of our reality,” Agnes says with a blink of excitement in her crystal-clear eyes. “The technosphere is already part of our biology.”

It has been scientifically proved that the daily use of technological devices is reshaping our cognitive patterns. But stopping at their physiological effect on the human brain would mean to look only at one side of the medal. With communication technology allowing a potentially unbound transformation of personality, we have long past crossed the borders of our own identities. What Agnes advocates for is an even more profound blurring of boundaries between collective and personal experiences, with technology as an asset.

In that sense, spiritual and digital spheres have several points in common. They are both founded on the connectedness of all things and understand the individual as part of a larger system.

Also their modes of communication, based on a dematerialized and potentially infinite chain of relationships, are not so dissimilar. “Even if my position remains strictly secular, I believe in a revival of magical thinking. Many ancient spiritual traditions and healing rituals are in tune with my approach, and I often adopt them in my performances as a way to conduct the audience in a state of surrender.” As in ecstatic experiences, sensorial attunement is the first step towards the highest achievement, which in Agnes’ intentions is the dissolution of the ego and a merge with harmony.

But in an era shaped by complex cultural and political relations and dominant neoliberal rationality, the path of human bettering is not devoid of controversies. The field of mindfulness practices has lately been put under attack, with a growing number of scholars shedding light on the links between a new kind of secularized spirituality and the privatization agenda. The presumption is that it is being used as a tool to make people cope with the pressures and injustice of capitalism as individuals, instead of taking joint action against them.

“It’s all about the intent. You can have the same text and use it for two entirely different purposes,” is Agnes’ answer to my doubts. “I don’t believe that one specific philosophy can rescue our existence alone. It would make it too powerful and thus dangerous. The way to unity is through the integration of a myriad of approaches and disciplines: old, new and not even discovered yet.”

Protected by the solid quietness of Švicarija on a mild January late afternoon, unsuspecting of what the world has in store for us in the weeks ahead, I tend to believe that what Agnes auspicates for is really at our fingertips. Her positivity is contagious, and even when asked whether her confidence in a future of oneness and wholeness is ever shaken, she brightens up: “We’re dwelling in abstract waters of future anticipation. At times a little boredom kicks in because things are not tangible enough yet. It would be my dream to see in the future, like a hundred years ahead!”

An exciting aspect of Ljubljana is its density in terms of architectural landmarks, which makes it easy to read its history by simply walking around and looking up. A few hundred meters north from the iconic Nebotičnik in the city center—which, upon completion in 1933, was the tallest skyscraper in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia—are the Metalka office building and, a few steps away, the Avtotehna Tower. Designed by Edo Mihevc in the ’60s, both business buildings appear in line with the current functionalistic style: two compact trunks with metal facades that articulate the skeleton elements externally. By bypassing applied ornamentation and undisclosing the bearing structure, Mihevc’s idea was to introduce a more honest conversation with the citizens.

In a sort of historic flareback, the 8th floor of the Avtotehna tower is now occupied by Osmo/za, a collaborative space for the unification of arts, sciences, technologies and humanities set up by three NGOs with an influential history in the production of open culture. A hotspot for artistic experimentation, civic engagement, ethical hacking and free circulation of knowledge, Osmo/za represents a creative frontline that is hard to label, and an alternative to the dominant cultural establishment. I find it fascinating that such a place is nested inside an edifice that symbolized the technological innovation of its time—albeit at the service of capitalistic premises. A karma balancing of some kind.

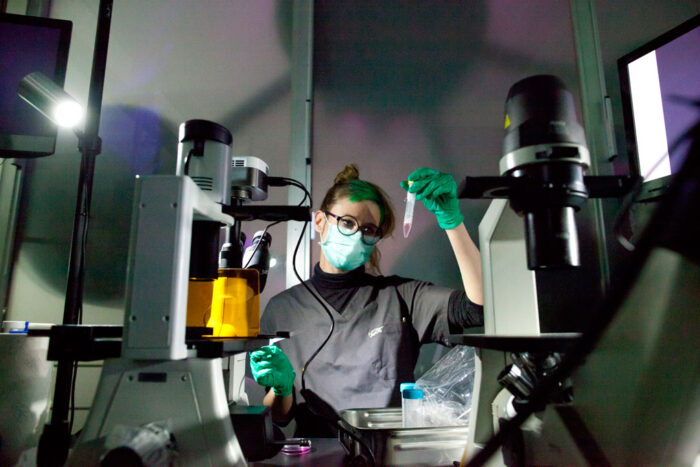

I am visiting Osmo/za to attend a guided tour of Vegetariat: Work Zero by new media artist and former scientific researcher Špela Petrič. The installation is displayed in the spacious atrium at the entrance and has the vague taste of a stage prop, with a structure of a folding screen made from three joined metal grid panels. Six drill machines are mounted on the central panel, turning on and off at (apparently) random times and speeds. On each drill, placed around the chuck as if it was a human wrist, a smartwatch. On the lateral panels, six potted plants.

Like the rest of the audience, I am both puzzled and slightly hypnotized by the intermittent drilling sound. Špela soon comes to our aid. She explains that the plants are connected through sensors to an Arduino system, which monitors their activity and transforms into inputs that activate the drills. And the smartwatches? They count the number of steps “taken” by the plants. Špela adds that the “smartwatch-on-a-drill” trick is a real hack, which owners of the wearable device can use to make it track walking at their place. Especially if aiming for a specific target that can make them gain rewards from the insurance company. Beyond being witty and catchy, the installation underlines the cold fact that there is no distinction whatsoever between humans and other-than-humans in the eyes of the algorithm. The binary script sees both as raw material giving away data to its own benefit.

Vegetariat: Work Zero is just one manifestation of Špela’s interest in exploring the possibility of intercognition between humans and plants. She started researching the question of plants’ agency a few years ago, moved by the desire to fill a millennia-old gap of comprehension in Western metaphysics. “The way we perceive plants in our cosmology goes back to Aristotle’s scala naturae, that hierarchically poses humans at the top of the ladder of life and plants at the bottom,” explains Špela. Accordingly to the model, the quality of rational thinking ranks highest, followed by the ability to move. Plants are situated at the transition between living beings and inanimate matter. “Which makes us look at plants as a plastic image of death, barely alive. But isn’t it all the more wondrous that plants can thrive, producing so much excess that they allow all the other organisms to exist?”

Intending to achieve a new level of kinship between humans and plants, Špela adopts an augmented materialist approach. Her point of departure is the traditional scientific method, based on the observation of nature in the form of experiments, which she expands by including experiential qualities. In her tests, the two subjects meet on equal premises through the performance of an often trivial exchange that subverts our usual point of view. It’s a queer position, in which the relational senses and the seek of contact play a fundamental role.

In Skotopoiesis (2015)—the first project of a trilogy titled Confronting Vegetal Otherness—Špela interacted with a carpet of cress stretched at her feet with the same adamant fervency of a new lover, casting her shadow on it for twelve hours a day. As a response to her presence, the plant morphologically changed, whitening and elongating its stems, while the artist’s spine slightly shrunk due to holding a standing position for a long time.

“My intention with this project was to establish a sort of economy of ethics, where the human and the vegetal bodies could be perceived as carrying the same value,” says Špela. A semiotic challenge, aimed at tackling the systems of conventions we rely on to interpret the signs around us. “At first, the audience could only identify with my presence and endurance. But after a few minutes of inactivity from my side, they reconsidered the elements at stake and started paying attention to the plant.” The artist’s shadow became an index pointing to the cress, allowing for a realignment of meaning in what was a conversation rather than a monologue.

When putting science and art vis-a-vis, and especially when aiming to connect with species other than human, the issue of translating the encounter into an intelligible output is crucial. The role played by the interface in this process is fundamental and double-sided. If, on the one hand, it is an often necessary element to make plant agency visible, on the other it can represent a hindrance to the connection.

“This was my biggest issue when I started working with plants,” confesses Špela. “The interface is often used to adapt the vegetal input to the human physiological setting, which erases the gist of the living organism behind it. To animate plants through time-lapse or music might be a convenient option for us, but it’s unfair to them. It only partially conveys the relation.”

Špela’s hands-on experimentation has provided her with a higher awareness of the delicate matter. From a lead-off position of employing as little mediation as possible, she has settled to acknowledge that the interface is unremovable. “My next opus is more playful. Humor allows me to use tools I’ve initially had problems with, such as consumer electronics. I just had to learn it the hard way.” The project Phytoteratology (2016)—the trilogy’s third chapter—provided part of the lesson.

In pursuit of an alternative view on reproduction and visceral relationships, the artist performed in vitro conception of a hybrid between plants and humans. She obtained that by extracting sex hormones from her urine and conjugating them with embryonic tissue taken from a common weed. After quite literally giving birth to a breed of aliens, she expected that she would nurture them as parents do with their offspring. But the incubators where the embryos were conceived made the newborns very weak and easily infected, to the point that not even their mother was allowed to touch them. “My aim was to subvert the traditional idea of family, that has pregnancy as central to its production, while still maintaining the physical bond as a possibility of care and affection. But the interface took over, subjugating both the plant and me,” explains Špela. “It was a frustrating, yet illuminating experiment. It exposed the precarity of inter-species love within the context of technoscience.”

At the time of our interview, a thought struck me. Here is the key to our comprehension of otherness: the acceptance of the vulnerability of the infrastructure. A vulnerability that we, as humans, share with all the inhabitants of the ecosystem we inhabit. A few weeks after, at the time of writing—a time of unprecedented biological crisis on a global scale—the same feeling is even stronger.

Science is an abstract apparatus that manifests itself through its own set of schemata, principles and procedures, whose effect expands into the individual’s decision-making. It’s a path of conduct that descends from the theoretical to the very concrete, personal level. If we substitute the term “science” with a social articulation of any kind, we will see that the same rule applies in pretty much all spheres of our lives.

When I ask her whether her Ph.D. in Biomedicine influences the way the theories she proposes are being received, she answers candidly. “Yes, to a great extent. My scientific background grants me an authority that is almost blindly accepted in the artistic realm. I’m aware and critical of the power that my position entitles me and I’m using it in a way that, I hope, is ethical.”

I met Neja Tomšič at her studio, located at Stara Tobačna—a huge factory complex squeezed between the railway and one of Ljubljana’s main boulevards. Meaning “Old Tobacco Factory”, Stara Tobačna has the stark appeal of 19th-century industrial architecture and the enigmatic charm of a “town in a town.” At the peak of its activity, the factory employed nearly 2.500 workers, meaning 8% of the city’s inhabitants at the time. Since 2011, with gentrification in full swing, it has progressively been reconverted in a cultural pole, and today is headquarters to a large number of artists, designers and architects together with start-ups, NGOs and small businesses.

The ex-industrial compound is a real maze of buildings with several entrances for each block; once inside, the space is fragmented in mezzanine floors and corridors departing in all directions, making it close to impossible for a newcomer to orientate. I happily accept Neja’s suggestion to pick me up at the janitor’s quarters, which looks as one would expect from a neorealistic movie: dim light, a massive dark-wooden concierge, a spectacled porter and a puzzle-like key rack behind him.

While we walk upstairs to her atelier, I can’t help but think that the match between Stara Tobačna’s symbolic presence and Neja Tomšič’s artistic interests is somewhat accurate. Over the decades, the former factory has embodied a dynamic meeting of tensions, strategies and behaviors; a juncture of collective narrations and private memories that Neja devotedly explores and makes visible in her practice. There is also a fascinating fellowship between tobacco and tea, both drugs carrying imperialist patterns that Neja brings to light in Tea for Five: Opium Clippers, her latest long-term body of work. In between a performance and a history lesson, the project revolves around a Chinese tea ceremony where Neja invites guests and serves them tea while telling overlooked episodes in the 19th and 20th-century commercial relationships between China and the Western world.

The origin of the artist’s interest in this specific topic dates back to 2014, during a two-months residency in Baltimore, Maryland. “My encounter with the city was intense,” Neja tells me while pouring me the first of many cups of delicious green tea. “The art scene is incredibly rich, and has a long history of activism. But, at the same time, big issues of segregation, violence, and opioid addiction affect the city. Although drugs were a problem in my hometown when I was young, the situation in Baltimore was unlike anything I’ve experienced before.”

Drug abuse soon turned into Neja’s main research topic. “Its effects are so evident and devastating, that I became obsessed about finding out how illicit drug economies have eventually become part of the big picture. Quite early in my research, I realized that the way opium first came to the US was through tea importation from the East Indies via maritime routes. And Maryland played a pretty crucial role in the process, because of the clippers.”

A clipper is a type of merchant ship designed for speed. Invented in the mid-19th-century in Baltimore, it soon became the main infrastructure for the Western importation of goods from Asia. The market pillar that enabled the real accumulation of capital, however, was illegal opium traffic: an invisible but enormously lucrative trade that provided the foundation for colonization. In parallel, many clippers were also used for the slave trade, transporting human workforce from the colonies to build railways in the US, or to mines and sugar plantations in South America.

“In other words, we could think of the clipper as the fire-starter of capitalism and the vessel of imperialism. That’s why I elected it as the symbol of both. I then decided to focus on five ships, collected facts and anecdotes about them—spanning from the first US merchant ship in China, to the arrival of the Chinese to San Francisco—and hand-painted their figures on the teaware I use for serving tea to the guests. And as a starting point of my stories.”

The cups and teapots are the visual compound to Neja’s storytelling, and a reminder of the global corridors of power hidden behind a simple, relaxing and often convivial gesture such as the one of drinking tea. I find myself casting a glance at my teacup, that is discreetly but regularly getting refilled by Neja. It’s a pretty common ceramic one decorated with a flowery pattern, in the style of those at grandma’s—no shadow of sailing silhouettes with dark souls. And though, to think that such stories of imperial domination belong to the past is astonishingly incorrect.

By way of example, the Forbes family actively engaged in the opium and tea trade between North America and China in the 19th century, amassing a vast fortune. In a world that we believe post-colonialized, the family’s prominence and wealth are still extensive, with members such as John Forbes Kerry serving as the 68th US Secretary of State from 2013 to 2017. A number of similar anecdotes are presented in Neja’s artist book Opium Clippers published by Rostfrei Publishing—cold facts that constitute only the tip of the gigantic iceberg floating behind decades of white supremacy.

The relationship between neglected stories, geopolitics and power structures is also the main interest of The Nonument Group, which Neja co-founded in 2011. The group is a multidisciplinary and international artist collective that maps, researches and intervenes on memorial objects, infrastructures and public spaces that ceased to serve their original—often symbolic—purpose. On their website, it is possible to access a detailed and in-depth database of “nonuments“, including some splendid examples of spomenik (the Serbo-Croatian/Slovenian word for monument) built during Tito’s domination. Whose retro iconography, I admit, holds a certain charm for me. In fact, the project’s aim and reach are much broader than a revival of yugo-nostalgia. Outside the web, it operates as a platform for a full spectrum of site-specific initiatives whose outputs span from artistic interventions to seminars in different locations in Europe and the US.

“The interactive side of Nonument Group kicked off in Baltimore as well,” tells Neja, “and the trigger was, again, the sense of uneasiness created by the urban and social fabric. Due to the city’s infamously high violent crime rate, walking in public space is limited, and the use of public space the way I know it is close to zero. Which, for me, was a big cultural shock.” Bron, Neja’s peaceful beagle, seems to ratify his owner’s disagreement by nuzzling his snout against her leg.

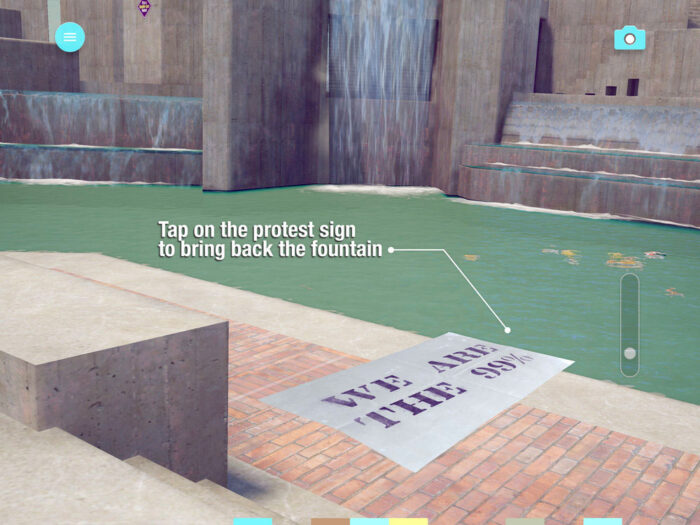

The area surrounding the McKeldin Fountain in downtown represented the only exception to this scenario. A grand brutalist monument erected in the early 1980s, the fountain turned into a safe spot where people would meet, hang out, dance, do sports. It became the hotbed of politically engaged organizations such as the Occupy Movement and Black Lives Matter, and one of the few officially designated free speech zones in town.

“But right at the time of my residence, I learned that the monument was earmarked for demolition,” Neja adds. “It came as a natural thing for me to join the group of activists engaged in preserving it.”

Despite the protests, the fountain was demolished and replaced by a plain grassland: an easier access to the nearby shopping mall, and an appropriate tabula rasa for the privatization of public space and the suppression of democratic values. Nonument Group—led in this project by Neja together with Baltimore artists Lisa Moren and Jaimes Mayhew—decided to rebuild the fountain virtually. They created an augmented reality app based on a full-scale 3D simulation of the monument, where it’s possible to walk around its paths, bridges, waterfalls and platforms, and hear about its legacy of everyday urban experiences and demonstrations from the voices of those who lived them.

“Personal narratives are what Nonument Group is all about, for me,” Neja observes. “I am not interested in the object as such, but rather in what it has meant, or still means, to the community around it.”

But in a time where the speed of information is doubling up every second and new architectures are being built every day, is it sustainable to keep on archiving and preserving the memory of everything? “That’s a crucial question. I see myself as collecting symptoms of the present, not memories of the past. I sometimes would like to think that, here in Slovenia, the most outrageous demolitions are behind us—both architecturally and politically. But the pressures in contracting the public and the common are stronger than ever.”

On my walk back home in the cold evening breeze, I think about the difference between nostalgia and memory. While the first can be an idealized response, the second is always connected to a space, a sound, a smell. It is precisely when the sense of physical belonging gets eradicated on a systematic level that social amnesia is irrevocably possible. And such amnesia spreads not only in remote places, but in our very own neighborhoods as well.

Size is nothing without sparkle. A way of saying usually applied to diamonds, but that can well suit art institutions too. On this matter, Ljubljana is a splendid example. The Slovene capital offers its share of physically large and sleekish redesigned art venues, including a whole museum quarter located in the once military barracks complex on Metelkova Street. What shines most, however, is the string of cultural gems nestled around the city: small and independent organizations, which, along the past three decades, have significantly contributed to the creation of a vibrant arts scene and fostered alternative modes of creative production.

One of the stones that have proven to be of the hardest material is Aksioma – Institute for Contemporary Arts, founded and run by multimedia artist Janez Janša, formerly known as Davide Grassi. After almost a decade of existence as a non-profit cultural institution, in 2011 Aksioma opened a 40-sqm project space in the city center, and it has made the most out of it since then. With a focus on new technologies and mass media, Aksioma has been tackling the implications of the “post-digital” in contemporary society by inviting and collaborating with established names as well as new talents. Among their many projects, in 2013 Aksioma has established U30+: an initiative dedicated to young artists that offers mentorship with art professionals and support in the realization of a solo exhibition. On the one hand, the program helps art students and freshly graduates to overcome the gap between the school years and the art world; on the other, it ensures Aksioma a constant update on emerging trends in the fast-paced evolution of mediated communication. Win-win.

Sara Bezovšek is one of the young Slovenian artists supported by the initiative. Born 1993 and a decade younger than me, she is technically as much a digital native as I am. In fact, the divide between our ways of speaking the digital language is pretty prominent. This is clear to me from our very first encounter—which, in an appropriate social media manner, happens on Instagram, where Sara manages multiple accounts. One of them in particular has me scrolling for more. It features moving collages and animated vignettes where emojis, stickers and icons are applied upon an amateur-like filmed background to create an immediate narrative. The result is a compelling series of condensed visual hybrids that could do just fine as a crash course on communication in the age of texting and social networking.

“It’s my sketchbook,” Sara defines it when we meet vis-a-vis, “where I upload short video clips I make when killing time. I have another account that I use professionally; this one is just for fun.”

The story behind it is as light-hearted as its content: “I put the first clips together when I started texting on Snapchat with the guy that is now my boyfriend. He’s a very creative person and I wanted to catch his attention,” she adds with a smile. “It apparently worked out.”

With a large part of contemporary romance taking place online, the overlapping between real and virtual life is so authentic that trying to separate and value them each in its own right would be senseless. And this is certainly not the only area of life that the Information Age has made blurrier: the same applies to the ever-growing interplay between leisure and labor.

In Sara’s case, what started as a pastime turned out as an affair that has equipped her with upgraded skills and specialized interests—including her vocation in the video-collage format, which is partly due to the basic necessity of circumnavigating copyright regulations on the use of emoji sets. While they may not be printed or made into tangible material, their application is free and unrestricted as far as it takes place on digital devices and online platforms.

“Contemporary cyberspace is marked by a clear disjuncture between free access and corporate regulations. Even if it’s a headache, I’m making the most out of it on the artistic level. Restriction is my resource,” Sara says. “Getting my head around these issues also led me to explore the concept of appropriation, which eventually resulted in the works that I exhibited in my solo show at Aksioma.”

The exhibition, titled (◉_◉), took place in 2018; among other works, it presented a trilogy of mash-up videos touching upon Internet-based forms of sexual harassment: Sextortion, Cyberstalking and Revenge Porn. As much as in most traditional movies, they have a clear narrative structure composed of a plot unraveling around a major conflict that is eventually resolved at the end of the film. But instead of through the ventures of specific characters, the story is told by a heterogeneous bevy of faces succeeding one another like in a relay race. By assembling various appropriated visual material such as GIFs, memes, social media posts and threads, clips from TV shows and movies, Sara portrays the Internet climate where many youngsters live a considerable part of their sex life: a place at once overcrowded and private, unshackled and slippery in the core rules of its etiquette.

“Remix is an inherent part of digital culture,” explains Sara, who so took the matter to heart as to make it the topic of her master’s thesis at the Academy of Fine Arts and Design in Ljubljana. And she is undoubtedly not alone in this belief. Copyright activist and co-founder of Creative Commons Lawrence Lessig sees the mash-up form as nothing less than an evolution in our cultural literacy. “Working with appropriated material from mainstream media culture and user-generated content is an excellent approach to storytelling, because a lot of people can easily relate to both,” Sara says. And she adds: “Remix is the most congruous way to visualize the current state of the world.” As well as the most effective in winning the attention span game: “If my five-minute mash-up videos were traditional short films with the same duration, I probably wouldn’t have the patience to watch them on my mobile or computer,” she admits.

Accepting that all cultural artifacts are open to re-appropriation is the entrance door to a play of mirrors where hierarchy is erased in favor of allusion, quotation, homage and pastiche. If there is a realm where this kind of attitude is king, that is underground music. While researching Sara’s practice prior to our meeting, I stumbled upon a track released in 2017 by the Ljubljana-based trap band Smrt boga in otrok (translatable to “Death of God and children”). The music piece has her name as the title, a montage of her Instagram collages as videoclip and gritty lyrics—at least as far as I can fathom with the help of Google translation. “A lot of it is in different slangs, including the local ljubljanščina,” Sara explains. “Not even my mum understands it all. Thank goodness!” When asked whether the track is a collaboration, a parody, or something third, Sara beats around the bush: “Let’s just say that they sing about a girl whose name happens to be Sara Bezovšek.” Fair enough, I’ll buy it: establishing and amplifying interpretative ambiguity seems in line with many of the instances addressed in our conversation.

Before saying goodbye, I share a thought that I had while enjoying her Instagram “sketchbook.” The witty tone of her clips—childlike, malicious and astute all at once—brings me to mind Hannah Höch’s collages and photo montages from one century ago. A pioneer of the Dada movement and a woman in a predominantly manly world (not that much has changed in this respect), Höch was convinced that art should radically undermine intellectual authority and cultural status, with humor as was a vital part of it. I like to think that if Höch were a millennial, she would be doing what Sara is doing.