Little Hope in the Art World

Giving up on your dreams is a prerequisite for success

The following essay is an excerpt from the book Can the Left Learn to Meme? (Zero Books, 2019). Utilising Adorno’s unswerving yet understated hope in spite of the odds, Mike Watson embraces the abstraction of the new media landscape as millennials refuse to surrender to cynicism, by out-weirding even the world at large. They pose a radical alternative to the right wing approach of Steve Bannon and the conservative psychology of Jordan Peterson. Here, the cultural elitism of the art world is contrasted with the anything-goes approach of millennial culture. The left avant-garde dream of an art-for-all is with us, though you won’t find it in museums. It is time the left learned to meme, challenging conventions along the way.

If you want to find out about artists and millennials, and whether any hope exists for either, go to art college. It won’t be quite the same as in 1998, or even 1988, when students and professors alike smelt of cigarettes and cheap booze, where every other student appeared to be stoned, and where disdain for authority was the default. But you might still find dreams, and people hatching plots to escape to a better world. Dreams and plots that begin with frantic scribbles and maybe take a more defined form over time. That is, if the student survives the pressure to conform to the contemporary art market.

Most people start out studying an art degree with some idea of why they are doing it, or at the least, with a definition of what art is. This idea may be hard to articulate, not least due to the low self-esteem of the average late teen. It may be expressed more as a feeling, an aspiration, a strong intuition—the kind of things one is encouraged to quickly overcome by the arts education system. By years 2 and 3 of a 3-year bachelor’s degree a feeling perhaps best expressed as “freedom” or “self-expression” is replaced by a desire to “interpret the world” to “entertain” or to expose political injustice.

Smart students by year three will have learned to pander to the exigencies of the market, while those who go on to study a masters and then—with all the luck in the world—sign up to a reputable gallery, will have hardened into agents able to cope with the cynicism of the contemporary art world. Somewhere deep inside of them the sentiment that inspired them to take up art school remains, yet it exists in spite of their arts education, and not because of it. In preparation for a life spent working in the contemporary art world, university turns our notions of what art is on their head. This chapter explores the battle between art as a form of self-development and critical inquiry, and art as a mirror of the world that the artist inhabits, complicit with its economic and political forms. Ultimately it asks whether the art world nullifies the creative tendency that might otherwise spur the millennial to challenge the pernicious prevailing political and economic conditions that characterize twenty-first century Living.

In some respects the gap between a budding artist’s hopes and the realities of the art world is nothing new. Van Gogh’s letters contain complaints about the mercantilism of the Paris gallery he had come to work in, while Jean-Michel Basquiat, the famed graffiti artist turned fine art painter, who shot to fame in the ‘80s complained bitterly of the pressures of art superstardom that eventually led to his death from a heroin overdose, aged 28. Though both of these artists at least went into their careers compelled to follow the spiritual-revolutionary path of the artist. In the twenty-first century it would be very hard to find an emerging artist who still holds the dream in mind. Artistic self Development is the preserve of the Sunday painter, the “outsider artist” and the mental outpatient, as the market has squeezed out any sense of idealism.

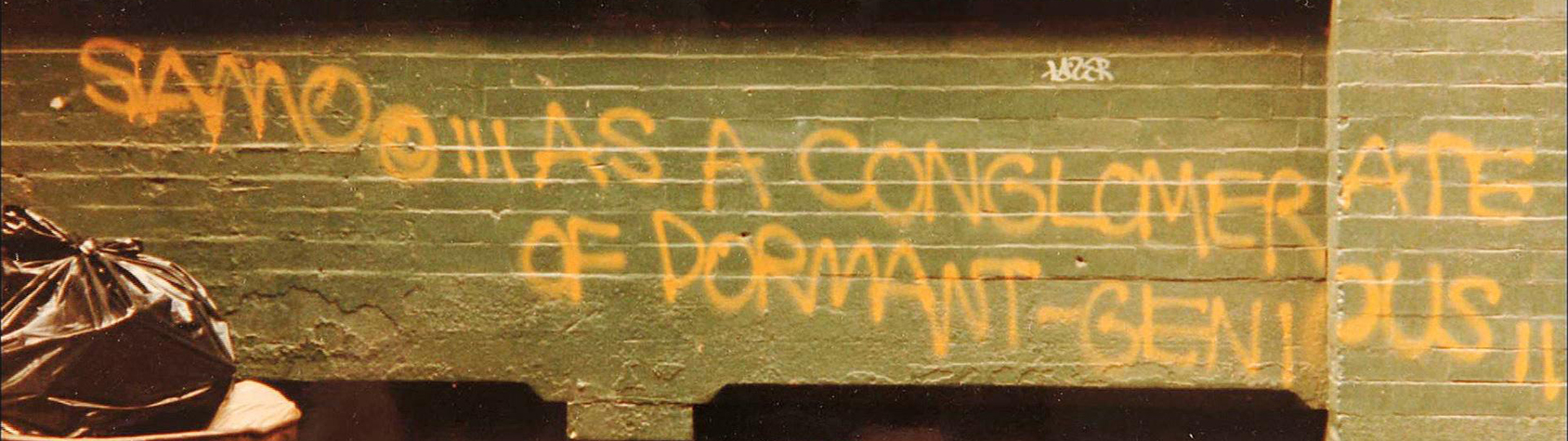

In its time, Basquiat’s meteoric rise was the stuff that dreams—whether of the spiritual or material kind—were made of. Born in 1960, as a late Baby Boomer, the artist embodied a vision of authenticity and of striking out at an elitist art world. The son of a middle-class Haitian immigrant father and a mother of Puerto Rican descent, Basquiat grew up in Brooklyn, where he excelled at school and showed promise as an artist from an early age. Aged 16 he began making street art as one-half of graffiti duo SAMO (meaning “same old shit”), capturing the attention of New Yorkers with scrawled texts that mocked the art scene and mass media of the time: “SAMO© 4 the SO CALLED AVANT GARDE; SAMO© AS AN END 2 CONFINING ART TERMS; SAMO© FOR THE SOCIALIZED AVANT GARDE; SAMO© MEDIA MINDWASH, SAMO© AS AN ALTERNATIVE TO PLASTIC FOOD STANDS; MICROWAVE & VIDEO X-SISTANCE- “BIG-MAC” CERTIFICATE FOR XMAS.”

By the age of 20 a mix of cheek, charisma and precocious talent endeared Basquiat to some notable New York personas, not least Andy Warhol, who immediately recognized the younger artist’s prodigious skill, and the young Keith Haring, who Basquiat met when he started to hang out at the School of Visual Arts in New York, where Haring was completing a BFA. Basquiat’s rise was so fast he had no need to study an art degree, though he did attend the Edward R. Murrow High School, founded upon the pedagogical didactic methods of John Dewey, emphasizing interactivity and democracy. Basquiat’s formation, however, took place largely in the art world. He was a rare example of an artist that hatched fully formed onto the international art scene.

Jean-Michel Basquiat with Andy Warhol. Photo: Michael Halsband

In 1981 Basquiat earned a stay in residence at the Italian gallerist Emilio Mazzoli’s farm, outside Modena, a small city in the region of Reggio-Emilia, after an initial meeting in New York when the merchant was so struck by the young artist that he purchased 20 works for 10,000 dollars and promptly organized Basquiat’s visit to the small North Italian city. In Modena, Basquiat would have enjoyed home cooking served at a large table where Mazzoli held court daily in front of an array of A-list Italian artists of the Transavanguardia. For the most part schooled in the Italian academies these artists were more formal than the strange new figure they found in front of them. Mazzoli explains, ‘The liberty with which he drew was shocking. Basquiat was rock…loud music, canvas on the floor, spray cans a go-go. A highly instinctive painter.” At times Mazzoli and his wife wondered if Basquiat would deliver, due to his haphazard working schedule. Notwithstanding cultural clashes, at the end of his 2-week residency a show was mounted, albeit to a lukewarm reception. Italy is a bastion of tradition, though beyond that its artists are notoriously “clicky”, sticking to their own friendship groups, which espouse more or less uniform opinions on art, and fighting hard to maintain their positions once they have become established. In spite of this, the show was a sellout, as Mazzoli convinced the local collectors of the value of his protegee. True to the art world, which is populated in part by a close-knit community of investors looking to back the next “big thing”, the impact of those first sales rebounded in New York the following year, when Basquiat sold out his first American solo show at gallery Annina Nosei.

By 1983 he was working in a space that prominent dealer Larry Gagosian set aside below his home in Venice, California and in February 1985 Basquiat featured on the cover of the New York Times Magazine. The edition carried an article entitled New Art, New Money in which Cathleen McGuigan discussed the explosion of the art market in the ‘80s: “‘As a result of the current frenzied activity, which produces an unquenchable demand for something new, artists such as Basquiat, Haring or the graffitist Kenny Scharf, once seized upon, become overnight sensations.”

The irony in Basquiat becoming one of New York’s hottest commodities in the span of 10 years and after being initially recognized for his anti-corporate anti-art world slogans barely merits pointing out. Though it is worth noting that the highest grossing US box office movie of 1984 was Beverly Hills Cop, a film in which off-the-rails and off-duty Detroit police detective Axel Foley (played by Eddie Murphy) exposes corruption at the heart of the Beverly Hills art scene. While managing to make his white colleagues look dumb, the fast-talking African-American Foley exposes gallery owner Victor Maitland’s use of art consignments to hide cocaine deliveries (which are in turn disguised as coffee).

“To Whites every Black holds a potential knife behind the back, and to every Black the White is concealing a whip. We were born into this dialogue and to deny it is fatuous. Our responsibility is to overcome the sins and fears of our ancestors and drop the whip, drop the knife.”

Avenging the death of his childhood friend in the meantime, Eddie Murphy’s portrayal was outstanding in its time (and effectively still is today) for the strength of its black lead character. Though what is often overlooked is the way in which Murphy rights wrongs at the expense of the epitome of white power and corruption: the art world. Unfortunately, however, real life does not echo fiction, at least not in all respects. The art world is for sure highly corrupt, though Basquiat—the outsider maverick that promised to unsettle it—ended up being sold out to it. In an essay on Basquiat entitled Radiant Child and appearing in Artforum in 1981, Rene Ricard stated, “To Whites every Black holds a potential knife behind the back, and to every Black the White is concealing a whip. We were born into this dialogue and to deny it is fatuous. Our responsibility is to overcome the sins and fears of our ancestors and drop the whip, drop the knife.” While questioning the sense in asking the “Black” to drop the knife that was in any case a figment of prejudiced “White” imagination, one could still ruminate that the proverbial “whip“ has never been dropped.

The signs of burnout from overwork at the hands of his overlords were clear by the mid-‘80s, as Basquiat used drugs to deal with the pressures of fame. He suffered paranoia and jealousy—at one point stating that “It’s as if I am just a protégé. As though I wasn’t famous before Andy found me”—and was reduced to making samey works to satisfy a hunger for his original vibrant pieces. His eventual overdose in his Manhattan art studio seemed, as so often, like both a suicide and resignation from a position he found untenable: that of superstar artist. With him, the Baby Boomer dream of countering the power base by challenging the symbolic order was dealt a major blow. Thirty years later the art world has not recovered. Rather, Basquiat’s treatment appears to have set a perverse standard.

For many people today this is a fact learned at art school, where the heady student expectations of unbound freedom and self-expression—the reason that many went to study art—are met with a crushing reality. Gone are art world high jinks, in favor of “core professional skills”, presentation skills, courses on copyright law, lessons on pricing your artwork and advice on how to ingratiate oneself to the art establishment. This has a further knock-on effect on the art world.

If the battle to assert one’s identity against a materialist and bureaucratic art world starts at university, it continues throughout the lives of many artists. While art school smashes the dreams of the budding practitioner, the art world itself is ready to follow up and cash in by processing the most financially promising via a soulless system aimed at minimizing artistic risk and maximizing profit. If art is about a free play of fantasy, the role of the gallerist is to dash dreams, starting with their own. Indeed, from artists who once entertained notions of free expression to critics who started out wanting to marshal the boundaries of good taste, to gallerists and collectors who formerly held dear to the idea of promoting and buying what they actually like to look at, the vast majority of art world players live in a state of abject disappointment. Giving up on your dreams is a prerequisite for success.

Perhaps no one has done more to highlight the ethically dissolute nature of the art world than the late John Berger—critic, novelist and poet—did in Ways of Seeing, the book and homonymous BBC TV series of 1972. “The art of any period tends to serve the ideological interests of the ruling class,” he argued, his eyes penetrating through the TV screen into the homes of an unsuspecting public that was curiously receptive to the news that both high and low culture were a cover for the malintent of the ruling class in Britain. At that point, with the British economy in tatters, the Baby Boomers—the original upstart generation—were beginning to experience a hard landing after the best part of a decade spent high as a kite. Great Britain wasn’t San Francisco and free love and hallucinogens were no solution to the problems posed by rising unemployment, a flagging economy and the miners’ strikes, which were called one day after the broadcast of the first episode of Ways of Seeing, on 12 January.

No longer could one look upon, for example, Gainsborough’s portrait of Mr and Mrs Andrews (circa. 1950) as a charming depiction of a couple enjoying rural England: Mr Andrews stood holding his rifle like some kind of public school educated cowboy bearing down on his wife, who is pictured trussed up like a wedding cake. On closer inspection their facial expressions appear sardonic, while their position in relation to the land (their land, nonetheless) appears to block the viewer from entry. The painting, which was executed in around 1750, appears as a window onto England’s rotten soul. Mr and Mrs Andrews are saying “keep out!” and the painting they commissioned nearly 40 years before the French Terror is a sign that the ruling elite were not prepared to share their spoils with the masses.

By 9 February 1972 a state of emergency and energy rationing was implemented in the UK due to cold weather conditions and a reduced electric current. Ten days prior to that, the BBC had aired the final episode of Ways of Seeing, in which Berger looked at image juxtapositions in magazines in order to throw light on the hypocrisy of the western world, which will happily countenance, for example, an advert for super strength alcohol or bath salts adjacent to images of starving Africans in a glossy magazine spread. Though perhaps more timeless as an image and more universal in its message was the episode’s closing sequence, which showed billboard posters urging voters to “Say Yes to Europe”, alongside advertisements for tobacco, Ford cars, tinned fruit, Captain Morgan Rum, Harp lager, the health benefits of cheese, and rail travel. As the sequence cut from billboard to billboard, taking in images of vagrants, passing workers and clothes drying on the balcony of a council house block, Berger’s voiceover brought his series to a close with a sense of melancholy befitting the scenery: “Our cities are papered with pictures of what we might buy, papered with dreams which invite us to enter them, but they exclude us as we now are. Behind the paper are hidden our Needs.”

It seems no number of Bacardi beaches can alleviate the gloom of a British city under a slate grey sky, though what stands out about Ways of Seeing is the way in which visual culture was implicated as not just an accessory but a principal actor in creating the disappointment, lack and want that characterized British life in the ‘70s. This is not to say that art is by any means the worst of pursuits and one can think of many more heinous career paths than “artist”: arms trader, people trafficker, politician, to name just three. Though the trouble for art—and by extension visual media in general—is that it enjoys the privilege of being the discipline responsible for expressing dreams. As such, it’s going to get hit especially hard when those dreams come crashing down. This is even more the case given art’s links to big business, finance and the ruling elite. So long as art maintains a veil of innocence it’s going to seem doubly complicit when the veil slips. Ways of Seeing was arguably the BBC’s most flagrantly leftist moment and certainly remains its most pointed critique of the cultural system in Britain to this day. Since its initial screening and publication as a book it has become a staple of college and university art departments across the world and is regularly referred to by artists as an influence on their work. It remains relevant despite one or two of its televisual sequences appearing embarrassingly dated.

When for example, Berger says in episode two of the four-part series (on the “male gaze”) that we might better understand the implications of female nudity in painting by talking to some—(gasp!)—women, the sensation is that the viewer at this point is being instructed to recognize Berger’s benevolence in so doing. In the ensuing scene a confident cigarette smoking Berger talks to five mostly painfully shy women about female portrayals in art so as to eke out from them a feminist analysis. As cringeful as this scene appears to be, it does take steps towards seeing the exploitation of women in the history of the image as on par with class subjugation: both are undertaken at the behest of powerful men, in conjunction with a compliant or co-opted image maker.

Whatever Berger’s failings—and they really belonged to the society he inhabited and found such fault with—his talent for reducing all injustices perpetrated by visual culture to a subjugation of the individual by objective image-making forces (Adorno’s “culture industry” in a nutshell) remains of use when examining contemporary society. This is crucial as any class, gender or race-based analysis of art risks becoming reduced primarily to a politics of resentment, thereby weakening its critical import. This problem commits the art critic or social theorist to a complicity with injustice of a second order, as her or his critique of the subjugation of people based on their class, gender, ethnicity or sexuality risks appearing as a shrill personal expression of discontent, and as such useless for fostering any collective response to injustice. For this reason, the identification of the impersonal objective forces at play in exploitation are fundamental to a reclaiming of culture, tactically speaking. In so doing we might better understand why we put so much faith in art as a kind of material expression of our inner dreamworld, and how it comes to fail us, generation upon generation.

At one extreme is the notion of the free individual artist-subject—the path of the spiritual Revolutionary—who creates new realities and is practically untethered by the objective or outer world. At the other extreme reside the materialist-conservative tendencies common to an array of artistic, curatorial and art historical practices, as well as to the activities of financially motivated players.

It would be an understatement to say that finding the right balance between subjective and objective critique is tricky. The issue of how much we credit to the “I” who looks or acts and how much to the “she”, “he”, or “it” that is looked at or acted upon is central to cultural, political, humanities and scientific discourse. It is a problem that won’t go away precisely because it concerns the conditions that make both human inquiry and interaction possible. Leaving aside the extent to which such a binary mode of reality might be a limitation of human enquiry itself, it is possible to construe the contemporary art world as a field of complex relations between individuals, institutions, art objects and finance mechanisms. At one extreme is the notion of the free individual artist-subject—the path of the spiritual Revolutionary—who creates new realities and is practically untethered by the objective or outer world. At the other extreme reside the materialist-conservative tendencies common to an array of artistic, curatorial and art historical practices, as well as to the activities of financially motivated players. Art, a discipline that arguably has subjective expression as an underlying premise is, one way or the other, remarkably well marshalled, cajoled and subjugated by objective forces that act to keep its message from unbalancing the social status quo. Yet at the same time, some degree of objectivity is required so that artworks can enter into the realm of visibility and exchange rather than existing as esoteric and closed artefacts of self-expression, personal fetish objects, trophies to peculiar personal interests or spiritual whims. Subjectivity and objectivity are, in whatever proportion—to be argued over perennially by philosophers—necessary to one another, in art as in life.

There is a familiar trope in detective films, wherein the killer’s lair—often a bedroom—is found filled with objects that pertain to his or her obsession: hair clippings, dolls, shoes, etc. Upon entering, the exclamation, unfailingly voiced by the detective is one of disgust as he or she casts their eyes over a personal display of macabre fetishes. The suspect has kept their “collection” to themselves, which is in itself arguably a sign of socio-pathological disorder. A body of fetish objects that remains isolated conveys, upon being found, a level of objectivity that is so reductive that it is dangerous to human life. In the movie Se7en (1995), the serial killer John Doe (played by Kevin Spacey) shocks Detective David Mills (played by Brad Pitt) as he enters Doe’s apartment with Detective Somerset (Morgan Freeman) to find its dimly lit halls playing host to an array of display cases embedded in black, grease covered walls. Objects on display—artfully arranged—include a severed hand from a victim and blood splattered books belonging to another. Se7en was a brutal and cynical film portraying a society with barely any remorse to the individual, yet even within the bleak portrayal of a New York nearly completely lacking in empathy John Doe stands out for the perversity of his materialism. His character is symbolic of the risks inherent in an entirely objective vision of property or people, with complete objectification manifesting in an objectification of people for its own sake (and not for show to others). Yet pure subjectivity would bring about antisocial behavior of a different order—that of the archetypal “madman” who, convinced that his or her chosen path is the path for all humanity, proclaims truth in the crowded marketplace. As such, the art world is charged with treading a thin line. The trouble is that the pact that art creates between subjectivity and objectivity is ultimately unconvincing, leading art to embody an antisocial behavior of a third type—that of the “con artist”.

Seven, 1996.

The term con artist is applied to people who play tricks on other people’s desires, usually as a means of extracting money. While applicable to any field it seems particularly apt to that of politics, where deception appears by now par for the course. This is perhaps because the politician so routinely finds her or himself held to a set of ethical criteria almost impossible to fulfil. In our age of citizen journalism and information leaks, where failures to live up to exacting standards of political life are promptly exposed, the politician is never far from a lie. The same could be said of the arts professional who, in having to convince an audience (or prospective buyer) of the transcendent beauty of an artwork—a beauty that might port us out of the sordid conditions of living—runs up perpetually against the obvious objectivity of the materials they peddle.

It is of course unsurprising that artifice stands at the centre of artistic practice. It is however interesting just how many players are openly and flagrantly involved in maintaining that artifice, and how deeply it extends into professional relations and business dealings that go way beyond the original artifice committed by the artist’s hand. Perhaps principal among these players is the patron or collector, without whom neither the objective material reality or the dreaming capacity of the artist would see the light of day. In Berger’s interpretation the art patron occupies both the top of the artworld pyramid and the top of the social pyramid per se. As such, via their financial strength they shape art to fit their model of society. What is crucial here is the role of money, which in governing society must also govern art. Accordingly, such art is put to service both in creating and protecting wealth. Specific activities come to the fore in a given society to the extent to which they are useful in the creation of capital. Consequently, the counter-capitalist tendency in art can only manifest when it is deemed useful to the generation of wealth.

The figure of the collector is fundamental to this course and through a process of commissioning or buying already produced works acts as a guardian of public taste, ensuring that what gets seen will never undermine the profit motive. Now, upon asking a collector how they choose what they buy, one will always be told: “I buy what I like.” Upon further probing one will find that “liking” is a gut reaction. A desire to help young or emerging artists will often arise as a further motive for collecting art. However, any time spent with collectors or gallerists reveals that they tend to operate via a kind of spread-betting, whereby they will purchase or promote a number of works from across a range of artists that look set to increase in value in the coming years.

What this effectively means is a steady rate of purchases from artists selling in the lower price bracket, who may enter into a higher bracket suddenly and at any given moment. The chance of an artist selling in a low price bracket suddenly achieving a leap in value greatly depreciates with an artist’s age. Simply, if an artist hasn’t enjoyed commercial success by 50, they are seen as unfit for making sudden profit.