Light and Shadow

A Recoded Contemplation of the Cosmos

Cosmos Cinema, the 14th Shanghai Biennale, is on view at Power Station of Art until 31 March 2024.

In 1917, the anarcho-futurist poet Aleksander Svyatogor introduced the intellectual and poetic movement of “volcanism.” He considered volcanic eruptions, with their torrential outpouring from the earth’s bowels to its upper surface, as phenomena that held the power to destroy all those temporal and spatial restrictions that relegate living beings into finite interpretations of the cosmos. The words of Aleksander Svyatogor open Cosmos Cinema, the main exhibition of the Fourteenth Shanghai Biennale, in which chief curator Anton Vidokle together with co-curators Xiang Zairong, Hallie Ayres, Lukas Brasiskis and editor Ben Eastham, propose to reframe the “terms of our relationship with the cosmos,” and their effects on earthly life forms. Through the works of about eighty artists, Cosmos Cinema refers to “diverse cosmologies and microcosmic realities” and encourages a reconsideration of current political, social and humanitarian threats. It is an exhibition conceived and composed as a film in which different narrative codes are interwoven into a montage of sequences. Artists’ individual works crossfade into each other, resulting in nine episodes, each of which endeavours to turn the different spaces of Shanghai’s Power Station of Art into—both in appearance and designation—a palace.

I: Freedom of Interplanetary Movement is the first palace, and the opening sequence of Cosmos Cinema. It is a dark, mastodonic, metaphysical space dominated by a sphere and a tetrahedronal structure, both mirrored and floating. They are Prototype for a Nonfunctional Satellite, (Design 4 Build 4) and Orbital Reflector (Triangle Variation #4) Scale Model, two prototypes for satellites that the artist Trevor Paglen made and launched into orbit between 2015 and 2018, proposing a form of space exploration free from and untethered to extractive and militarized mechanisms. The prelude of Cosmos Cinema thus begins with an aesthetic statement on the cosmos as the “most powerful catalyst of our imagination.” It goes on to propose a rethinking of our assumptions about space and time. Mono no aware is a composition of hanging sculptures made in 2014 by artist Shi Hui, known for her expansion of traditional Chinese weaving techniques into visual spaces and anti-form reflections. In Mono no aware, she gives an insight into cinema not as a modern technology but rather as a cosmic phenomenon with unlimited potential. In manufacturing a series of cubes, on whose faces she encapsulated and captured several everyday objects, Shi Hui proposes a form of proto-cinema that is strongly detached from the physical and technical interpretations of the photogram, i.e., “writing with light” (from ancient Greek φῶς, φçωτόςç; phōs, photos “light” and γραφία, graphia “writing”) or “collection of shadows” (from the Chinese 摄 “take in” and 影 “shadow”).

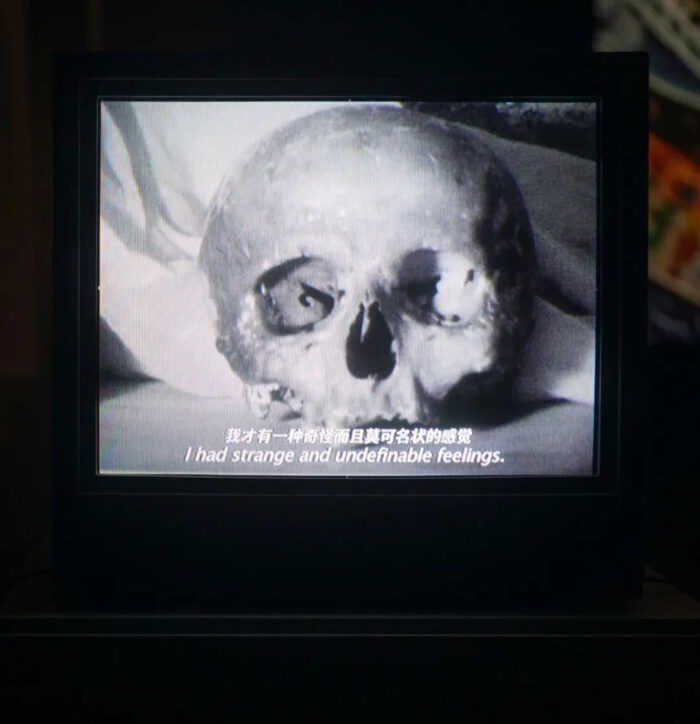

The limits of scientific objectivity and abstract logics are exposed in II: Partial Eclipse, the second palace of Cosmos Cinema, in which works of art are dedicated to obscure and unknowable cosmic phenomena. Johanna Hedva’s THE CLOCK IS ALWAYS WRONG (INK) is a vitrine display with an automated inkwell/clock inside it that ritualistically pours a drop of magically charged black ink onto a sheet of paper. Through the alchemic and divinatory dimensions of this artefact, Hedva examines several temporal conundrums: their cyclicality, uncanniness and indefiniteness. In the film Somewhere Beyond Right and Wrong, There is a Garden. I Will Meet You There, Yin-Ju Chen uses images collected during her travels, combining animations of mythological figures and found footage, to expose the cosmic nature of our relationship to life and death. Lucile Desamory’s short film Dark Matter hives a reportage on the emotional and psychological effects caused by events that alter the construction of reality, such as the real life experience of a woman who witnessed the landing of a UFO in her garden in 1989.

A switch of register in the exhibition montage ushers us from a prelude into a phase of non-linear intelligibility where “connections can be made by jump-cuts” and where a kaleidoscopic fade exposes countless perspectives. III: Ten Thousand Things is Cosmic Cinema’s third palace and also its actual beginning —indeed, this is where the exhibition opening credits appear. Here, Grounds of Coherence #1, but this is the language we met in by Shen Xin undertakes a linguistic exploration which interweaves Mandarin, Arabic and English words with other idioms and images in a single-channel video that engages ways of coming to knowledge and with ecosystems of language. Meanwhile Kidlat Tahimik’s two fictional and fictitious screening rooms compare two different film genres: Cinema Indio, Cinema Tonto. Tahimik is a key figure in the history of independent Philippine filmmaking, and his movies and installations always revolve around a focal point: how colonizers subjugate Indigenous peoples by first destroying their mythologies. For him, Cinema Tonto thus serves as a “Trojan Horse for the tontoization” of people and a hegemonic and neocolonial device that turns everyone into constructed characters. At the same time Cinema Indio is instead a form of indigenous storytelling in which a shaman leads a group of non-characters to project their imaginations rather than acquire and reproduce already-determined imageries. This comparison between Cinema Indio and Cinema Tonto is both naive and wise, giving a poetic and political reading of the surreal absurdities, inequalities and syncretism of the really existing capitalist world.

Ho Rui An’s Lining is a film essay exposing the economic, social and political relations that obtained from 1946 to 1997 between the then-British colony of Hong Kong and mainland China. Interviews with former factory workers and managers, archival material and new footage are edited together to understand the historical transformations of labor, technology and capital that led to the rise and decline of the textile industry in Hong Kong and its consequent transformation into a real-estate financial hub. In this manner, Ho Rui An opens the fourth palace of Cosmos Cinema, IV: Solar Assembly Line, which functions as a zoom lens on the connections between celestial bodies and terrestrial economics, finance and politics. In Potlatch of Derivatives, artist Payne Zhu stages the interiors of a rather shady place of gambling and forbidden vices, which like an untouched crime scene preserves the evidence of innumerable financial derivatives. After this factional excursion into time and space, Cosmos Cinema visually takes a pause with its fifth palace V: Cinema Cosmos: a dark screening room animated by a sound installation by Carsten Nicolai that intermittently mixes with a weekly program of screenings, presentations and discussions.

Like a flashback, VI: Futurisms, transports us into visions of future belonging to the past. Indeed, a selection of works from the George Costakis Collection shows how a generation of Russian avant-garde artists such as Gustav Klutsis, Alexander Rodchenko and Olga Rozanova regarded themselves, throughout the 1920s and early 1930s, as prophets of an age in which humans would leave earth to conquer cosmic space. This flashback turns into an actual time-travel that leads to the encounter between Stanisław Lem’s 1961 science-fiction novel Solaris and its film adaptations. Through Andrei Tarkovsky’s and Steven Soderbergh’s transformations of Solaris into a relationship drama, this almost-satirical sixth palace’s room transposes Lem’s fear of having reached the limits of our knowledge while also displaying the philosophical, epistemological, and ethical difficulties of depicting life beyond earth. He Zike’s science-fiction movie Random Access wrap up this futurist flashback by taking us to a rather present future, specifically to the city of Guiyang, home to the world’s largest radio telescope and to the “data center cluster” that is pioneering the rapid expansion of China’s digital industry. Here, a taxi driver and her companion move through urban spaces contemplating ancient memories and discussing future imaginaries, but most importantly in search for a way through the rapidly-changing world.

By continually asking “where are we heading?” and by blending both fiction and reality with future, past and present, Cosmos Cinema is, up to this stage, a montage that exposes the structural divisions that have narrowed and still narrow our interpretation of the world. In the seventh and eighth palaces, a sudden shift of focus reorients to the many imaginative and mediating practices that can be mobilized to reframe our relationships with the cosmos. In VII: Reflexology at a Distance, Maria Lai’s Senza titolo (Untitled) and Fili di geometrie (Threads of geometries) exemplify how practices such as weaving and embroidery, can be used to project into infinity but also to reconnect broken ties, while Zhang Wenxin’s photographs taken in karst caves invoke a break with the understanding of inside and outside, above and below, dark and bright, advocating the superficiality of such binary habits of thought. This also resonates in the eighth palace, VIII: Of Time and Space, in which alternative ways to overcome colonial and dominant cartographies are proposed. In Zhou Xiaohu’s Garden of Earthly Delights (2016), eight immortal puppets move between contrasting geographies, such as the idyllic landscape of south Zhejiang and its decaying industrial zones, to arrive by boat to the exhibition in an indecipherable state of divine revelation, delirium, or madness.

With these evocations and invocations, Cosmos Cinema reaches its conclusion, or rather epilogue. In IX: Brave Wind and Rain, the ninth palace, Mao Chenyu’s The Cosmists of the Ximao Household offers a final reflection on the world of the living and its geological narratives, and improvises a response to the “cosmic movie” in which we are all entangled. The curators, nevertheless, leave us with a series of questions regarding the many visions of the cosmos they have proposed, and how these visions may alter our interpretation of space and time. In particular, they ask what are the implications within the described patterns that still negatively affect the systemic orders in which we live and the decisions we make. However, what emerges from these nine palaces, and the contemplation of the cosmos they offer, is that cinema can become a cosmogonic tool for recoding our connection with the universe and, most importantly, for standing against the widespread apathy that prevails today amidst ever-increasing violence and destruction.