Laying Horizontal

On vulnerability, interdependence and resistance, or on reclining, collapsing, reversing and lounging

In February, I had the pleasure to come across the online event Being Horizontal: Vulnerability, Interdependence and Resistance curated by Nora Heidorn for Confabulations, a series of conversations on health, medicine, and medicalized bodies triangulating three areas of practice and scholarship, each with their own lineages, disciplinary ambits, and trajectories of remembering and forgetting. This specific event featured films by Nashashibi/Skaer, Kinkaleri, and Teatro da Vertigem, and a performance by Harold Offeh, followed by a conversation with Felicity Callard.

Quoting from Nora Heidorn’s opening speech: “In the works presented this evening, the acts of reclining, collapsing, reversing or lounging are deliberate and performative. You will notice that there is barely any speech in these works; tonight, we will feel out the embodied knowledges we have about what it means to move into varying degrees of incline, and to be looked at, painted, photographed, or filmed whilst being horizontal.

We might associate recline with sleeping and resting, with having sex, with being unwell, injured and, indeed, with death. In these artworks, I read going horizontal as symbolic acts with different meanings in different situations.

Moving the body into horizontality, physically and perhaps psychically, removes the body from the spatial and temporal playing field of the present moment. The loss of verticality, whether intentional or due to circumstance, temporary or permanent, may indicate an altered state, a different mode of being. The horizontal mode contradicts the standard enlightenment representation of the human body as male, singular, upright, autonomous and able-bodied.

This is an ideal which women, children, and others considered a little ‘less than human’, less rational or more dependent, could never fully achieve. The feminist philosopher Adriana Cavarero’s 2016 book Inclinations: A Critique of Rectitude makes clear what is at stake in being horizontal. She writes that ‘philosophy, in general, does not like inclination. It contests and combats it. Its methods are numerous and varied, depending on the epoch, but all are, in essence, as Foucault would put it, dispositives of verticalization, the aim of which is the upright man—or, the righteous man.”

Since the conversation leant on some of my interests at once, I decided to ask Nora (more than) a few questions.

Giulia Crispiani: The project revolves around two terms, namely recline and inclination, and I wanted to ask whether you see them as synonyms?—There’s a list of verbs you cite at the beginning of your “opening speech” which I chose to re-mention above to amplify the (comfy) linguistics around horizontality, as a threshold toward vulnerability.

Nora Heidorn: First off, I’d like to thank Allison Morehead, Imogen Wiltshire and Fiona Johnstone for hosting this event as part of the series Confabulations: art practice, art history, and critical medical humanities. Thanks to the artists Nashashibi/Skaer, Kinkaleri, Teatro da Vertigem and Harold Offeh for allowing me to show their work.

The words inclination and recline are central to this research project and the curated screening that took place in February. I see them as more than just a momentary shape the body might assume. If we pay careful attention to take both recline and inclination and what they express, they can be read as a different mode of being, a way of thinking about the self as always fundamentally in relation with other people and our more-than-human environment.

The two words are not exactly synonyms: “to recline” is to lie down or to lounge, to be really horizontal, although perhaps one elbow is propped up to raise the head. We often recline to sleep or rest, or to cuddle or have sex. Americans call chairs on which you can lower the backrest and raise the feet “recliners”. But we also recline in certain culturally choreographed situations, for example on the doctor’s high examination bed, on a towel at the beach, or for spa treatments. These acts of reclining are less private and more to do with being observed or touched.

Inclination is more subtle and often a fleeting movement: it means to lean or bend, for example bending down towards a child or an animal, or leaning on someone’s shoulder. Inclination is a geometrical descriptor of a diagonal line, a tilt out of the vertical axis. Whereas recline is often held for some time, inclination is more of a movement, a direction. An inclination can also be a personal tendency or disposition of the mind, a preference. We usually incline towards someone or something, to attend to something, look closely, to take care of something or to receive care and affection. It is an inherently relational concept. The feminist philosopher Adriana Cavarero, whose work informed my thinking around this project, has theorised inclination as a feminine way of being in the world in contrast to the masculine, vertical ‘I’. The feminine inclined is mutually dependent with others and situated in its world; it leans out of the vertical axis of the “I” towards other creatures and things. Unlike the masculinist ideal of the individual, it does not imagine itself as independent, self-sufficient, and purely rational.

In the films and in the performance I’ve selected for this event, bodies recline to be looked at, they suddenly collapse in front of the camera, they move together backwards, they lounge and hold a pose. There is a tension between movement and stillness, and between individual bodies performing, collective movement, and our own gazes onto these films.

After the introduction the first image that came to my mind is a gaze looking at a sleeping body—which is something that returns also in the film by Rosalind Nashashibi and Lucy Skaer, Why Are You Angry? (2017) where we’re looking at bodies that are all but dormant. In both there is this tension between a desiring gaze vs someone having to endure a gaze, between tenderness and voyeurism, between a subject and an object. Taking this from horizontality, I feel something changes if we’re both consensually horizontal, or inclined toward each other. What do you think?

Exactly, these films negotiate horizontality and inclination in relation to the gaze, power, and relationality. Lying down together to rest is a very different feeling to lying down in front of someone who remains upright and looks down onto you. Even if nothing happens, there is a power dynamic at play because the one who is upright can more easily act upon the one who is reclined. It takes some time to get back up onto one’s feet from a reclined pose (if one can). To recline is most often also to be prone and vulnerable. That’s why watching someone sleep is so intimate: if we aren’t very close and comfortable with the onlooker, it feels intrusive. We also culturally associate bodies in recline with specific experiences of vulnerability that are endlessly repeated tropes in our visual culture: the sick person, the birthing woman, the homeless person, the fallen soldier, the psychoanalysis patient, the person on their deathbed, the sleeping child…

Nashashibi/Skaer’s film Why Are You Angry? explores these dynamics. Rosalind Nashashibi and Lucy Skaer grapple with the legacy of the French painter Paul Gaugin, who painted his most famous works of young models in Tahiti (at the time French Polynesia) in the 1890s. Gaugin left behind his wife and children in Europe to start a new life in Tahiti. He imagined it as a kind of untouched paradise brimming with more “primitive” pleasures. Gaugin took several young lovers and a child bride, Teha’amana, whom he abandoned soon after while she was pregnant. She appears in several paintings. He also most likely contracted syphilis to several of his Tahitian lovers, a disease of which he would later die. The economic, gendered, and colonial dimensions to Gaugin’s work in Tahiti had long been overlooked by art history, which likes to produce male geniuses.

To make their film, Nashashibi and Skaer somewhat retraced Gaugin’s vision of Tahiti. They asked local women to assume some of the poses in which Gaugin had painted his models: reclined on a bed draped with colorful cloths, belly down, or dancing together in a courtyard with chickens and dogs around. Just like Gaugin’s paintings, the film is lush, colorful, tropical. But the camera takes its time to watch the models lie down and move into the pose, it lingers on their faces and bodies, and it keeps watching as they get up and wrap themselves in a sarong, perhaps give the camera a shy smile. These are some of the most powerful moments of the film: the awkwardness, the discomfort of posing and being imaged naked and reclined, these subjective responses to the gaze of the camera which are normally edited out. The film somewhat re-enacts Gaugin’s acts of looking at and imaging Tahitian women, but it does so with a lot of critical questions. I first saw this film at Tate St Ives in 2018 and was completely mesmerized by the beauty and slow rhythm of this 16mm film, whilst at the same time feeling complicit with the camera’s—and by extension Gaugin’s—gaze. The film hovers ambivalently between re-enacting and repairing that violence, which I think makes it so powerful.

What do you think we might imagine or wish for as an opposite posture to the straight and vertical “I”?—this is a question that is particularly dear to me, in my everyday practice, and I am curious about your point of view, also in regards to Cavarero’s theory.

I would love to hear more about your thoughts about another pose to replace the vertical “I”!

For me, it is less about a pose than about “doings”, ways of engaging with the world. I’m influenced by Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, who writes in her book Matters of Care that caring for things involves practical “doings”. I think through inclination in relation to my practice of researching, curating, working with artists, writing, and teaching. Cavarero’s book helped me to clarify that for me, curating is fundamentally a practice of inclining: even when a curator works more or less on their own, or with historical objects in a museum, rather than in collaboration with living artists, it is fundamentally relational. Curating always involves inclination outside of the self and one’s own inner world towards things or people beyond the self: their ideas, the things they make, do, write, leave behind… This inclination can work across time (i.e. engaging with history or the future) and place. Curating is attending to, learning from, staging, and mediating the ideas and things of others. This is not to say that curating is inherently “good”: these actions can also be violent, for example the representation of looted objects from colonial contexts without consideration of the communities of origin.

So I ask myself, what responsibilities come out of that for me as a curator? When attending primarily to one’s own ideas and experience, one is accountable only to oneself, can disappoint only oneself. Inclining towards the work of others requires an ethics of care. The question of care (how to care?) is a crucial question for curating, I think the crucial question.

Yes, indeed. So, what does horizontality have to do with resistance in this particular research? And how did it formalize?

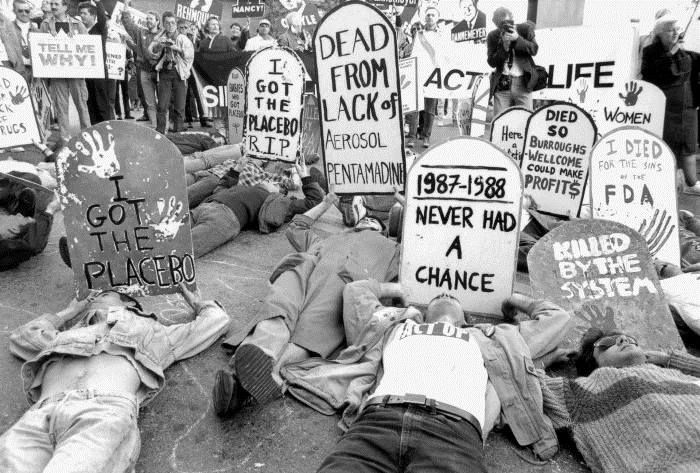

I’m interested in how activists and protest movements have emphasized their vulnerabilities and “performed” them very consciously towards those in power in order to demand change, to demand care. I’m thinking for example of the “die-in” protests by AIDS activists in the 1980s, or recent protests by wheelchair users in different parts of the world demanding access and healthcare. On the one hand, you can build solidarity and structures for mutual support and organizing by sharing vulnerabilities. The demand for care (for example from the state) becomes visible and palpable when vulnerable and marginalized bodies that are otherwise not very visible suddenly occupy public space. I think even outside of activist struggles, in much more everyday situations, sharing vulnerabilities and needs is inherently political, as it contests that idea of the vertical “I”: the autonomous, endlessly productive, able-bodied individual, which is an enlightenment fantasy.

In the artist films presented, resistance can be traced in subtle or overt ways: the women filmed by Nashashibi/Skaer re-enacting Gaugain’s models’ poses return the gaze of the camera, making it a protagonist. Those returned gazes highlight the objectifying dynamics of posing naked to be imaged. The returned gazes share the awkwardness, embarrassment, and also the knowing pride of the situation, which I think leads to a mutual acknowledgement and questioning of exactly those dynamics between the subject in the film and the viewer. In Teatro da Vertigem’s film Marcha à Ré, the performative action is more obviously a form of protest responding to a current political and public health crisis. Here, slowness and reversal of direction are used as performative devices to question and critique the status quo.

In Kinkaleri’s work WEST specifically, is collapse a symptom or an effect, or both? In the anti-productive rhetoric, it is also a form of resistance—if we read collapse as agency (amidst other bodies that don’t blink an eye and move forward through their day).

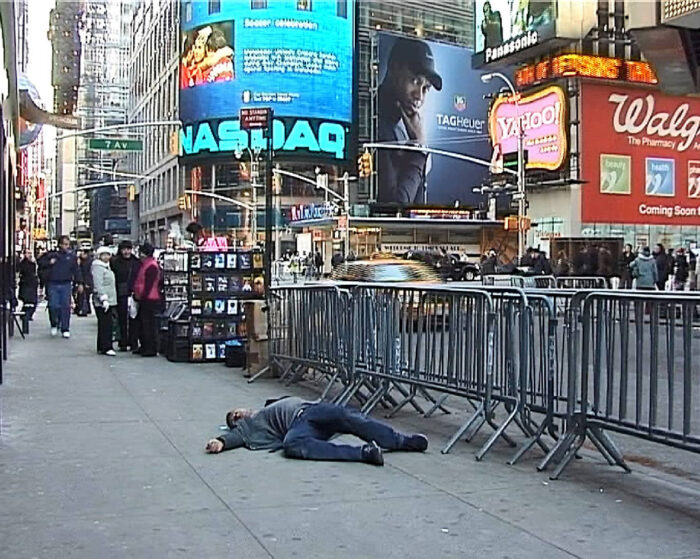

Kinkaleri is an Italian performance collective. Their project WEST (2001-2008) was performed and recorded across twelve cities during a period of seven years. In each place, members of the public were enlisted to perform a single gesture—a collapse—in public space. This same act of falling is repeated by a legion of anonymous bodies in busy urban spaces until, eventually, the collapse takes on symbolic and metaphorical qualities.

Kinkaleri’s project was shown also in an exhibition I co-curated with Mira Asriningtyas and Kari Rittenbach at Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in 2018. Returning to this durational work some years later and showing it in a new context felt fitting. I like the idea of a return, of engaging with practices repeatedly over time, and this really resonates with WEST, in which the collapse is performed repeatedly, literally for years.

Like you, I read the loss of verticality in collapse as physically removing the body from the spatial and temporal playing field of the present moment. The collapse is an opting out: might speak of no longer being willing or able to participate. The title of the work WEST, and the fact the work was performed in post-industrial major cities of the global north, prompts a political interpretation of the work. Collapse may be an effect of late capitalist hyper-productivity and ubiquitous connectivity, but it could also signify the end of an era in which “the West” dominates global politics, economy, and culture. We have transitioned into a different world order in which other global and regional powers exert their influence, long before Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

Kinkaleri don’t describe the work in terms of productivity, capitalism, global power structures and resistance—this discussion is for their audiences to have. Interestingly, I’ve always thought of the act performed in WEST as a collapse, but Kinkaleri refer to it as a “death”: they asked volunteers to fall “as a dead body falls”—but not with too much pathos—and to lie on the ground with eyes closed. The sudden fall was developed out of a previous live performance piece, in which this one gesture turned out to be particularly poignant.

With WEST, Kinkaleri were interested in the composition of these scenes: an upright figure staring into the camera, creating a rapport with the viewer and then suddenly collapsing. The stillness of the fallen body brings the cityscape to the fore and the collapse highlights vertical and horizontal compositional lines in the background. As the body remains still, the city keeps moving, often in horizontal directions. Even though this is a video work, there is something inherently photographic in the carefully framed scenes and the still figure. Like in Nashasibi/Skaer’s film and Harold Offeh’s performance, there is a tension between action and stillness, between movement and pose, and between the gaze of the performer and our own.

A metaphorical and political reading of WEST is not new: in an essay about the work from around ten years ago, Antonio Grulli remembers the news footage of people falling from the Twin Towers in 2001, the year Kinkaleri began this project, the end of an era. This cataclysmic event might no longer be the immediate association for viewers today; perhaps a 2020s interpretation of this work revolves around the exhaustion, anxiety, inequality, and sickness of late capitalist pandemic time: a crip reading of WEST. The questions of agency and resistance are ever more pertinent when there is no “outside” of racial, extractive capitalism and a different world is hardly imaginable, but I think there is still potential for resistance in slowing down in the face of ever-increasing demands to be productive, of retreating in the face of hyper-visibility and over-sharing. The question is how to come together in such gestures of subtle resistance, which can easily contribute to further individualization and fragmentation of our communities.

Going back to the film Marcha à ré [Reverse gear] (2020) by Teatro da Vertigem, there’s a sense of mourning which also is or used to be in its rural archaic form some sort of collective “resistance through letting go”. How would you read this specific intervention as posture?

The Brazilian theatre collective Teatro da Vertigem orchestrated Marcha à ré in Sao Paulo in 2020. For this performative protest and funerary procession along a central Avenida, over 100 cars drove at very slow pace in reverse gear, against the usual direction of traffic. A trumpeter played the Brazilian national anthem in reverse. The site-specific intervention took place at the height of the pandemic, taking public space to mourn the victims of Covid-19. I understand it as an artistic critique of the right wing, populist president who severely mismanaged the public health crisis. A film of the intervention by Eryk Rocha was premiered at the 11th Berlin Biennial last year.

I was really drawn to the acts of reversal in this project. The reverse movement of traffic has a mesmerizing quality that is similar to the falls in WEST. There is a sense of time suspended, of a surreal state of exception that accurately reflects the sense of crisis and existential angst of the first months of the pandemic. In Brazil, the severe mismanagement of the pandemic and the neglect of the most vulnerable members of the population caused an ongoing disaster. The national anthem played in reverse becomes unrecognizable and alienating—the opposite of a patriotic tune that brings people together in a shared sense of belonging. At one point, the rather documentary observation of the camera rotates and the city is literally upside down. So in this film, there is this unusual combination of the ominous feeling of a disaster movie and the crawling pace of a funerary procession, which is really affecting. It must have been incredible to witness this happening in person, from a window in a high rise tower or as a pedestrian on the ground.

I think about the reverse movement characteristic of this work not so much in terms of pose, but as a form of resistance that functions similarly to the collapse: things are not right and moving ahead along with the usual flow is no longer possible. This work brought the important aspect of collectivity to the programme: how does a collective movement into reverse make for a powerful performative and also political gesture?

During the AIDS crisis from the early 1980s, activists staged die-ins in the USA, where they would collectively lie on the ground as if dead in front of key centers of power, such as the white house or the FDA. They had styrofoam “gravestones” pointing out that deaths by AIDS were deaths by government neglect. I want to make a connection between the film and these earlier protests, which are both about health crises caused by deadly viruses. The performative action of the “die-in” spread to other countries and was taken up decades later by different protest movements, such as cyclists protesting the risk to life in urban traffic, or Extinction Rebellion highlighting the man-made mass extinction of species in our ecosystems. The collective collapse of the “die-in” or the slow-motion reverse movement occupies urban space and addresses power directly through performing vulnerability.

It was really interesting to listen to Harold Offeh describing his performance, on the concepts of holding a pose as taking a posture/inclination, and the implications around projection of the image vs the actual mechanic. The active engagement of “holding still” to “occupy a public space.” (I think this is more of a comment than a question but I’d like to retell some of what has been said considering those who didn’t witness the event.)

Harold Offeh’s performance and his related photographic series Lounging (2017-ongoing) re-enact relaxed poses of recline that were typical of album covers of black male singers in the 1970s and 80s. With this work, Offeh asks what it means for the black masculine body to occupy space through this pose, which he compares to sitting at a protest.

It was so brilliant to host a live performance to web cam by Harold after screening the three films during the online event. Harold had set a background image on his Zoom tile of the R&B singer Teddy Pendergrass lounging on his side in a white suit, propped up on one elbow. In front of this image, Harold imitated the pose, also in white, trying to perform the photographic image in real time: we watched Harold blink his eyelids, inhale and exhale, relax and soften his body, and then become alert and active again by tensing his core and returning his full concentration to the pose. For me personally, the performance was strangely difficult to watch for the whole five or six minutes, and eventually became funny. I really enjoyed this live element in an otherwise very controlled event, especially because I hadn’t seen Harold perform this work before myself.

In the discussion with medical humanities scholar Felicity Callard at the end of the event, Harold spoke about the implications of this lounging pose for the Black singers he researched: it conveyed approachability and relaxed confidence in a racist culture that routinely portrays Black men as threatening, violent, and criminal, at a time when Black singers broke into the mainstream (white) music market for the first time. The lounging pose also speaks of leisure: to rest and enjoy free time (and to be seen to do so) is still often a white privilege, as Navild Acosta and Fanny Sosa’s project Black Power Naps also highlights.

How did this approach and conversation to-and-from critical medical humanities come about? How were these alliances built? I love what Felicity Callard said about “establishing illnesses as a way of cutting through” and the reflection around imposed horizontality vs pose…

In around 2016-17 I became really interested in feminist critiques of medicalization and pathologization of gendered and racialised bodies, as well as in the privatization of care. Helena Reckitt pointed me to Johanna Hedva’s Sick Woman Theory, now a seminal text for disability studies and activism, and Paul B. Preciado’s Testo Junkie, while I was studying with her in London. I became really interested in the politics of hormones in relation to the menstrual cycle and contraception, which led to an essay which you published on NERO. Simon Sheikh invited me to make the exhibition and public programme Sick and Desiring for Bergen Assembly 2019, for which I commissioned new work from brilliant artists working on questions of healthcare, reproductive justice, and alliances between women and animals in the face of violent medical and carceral practices.

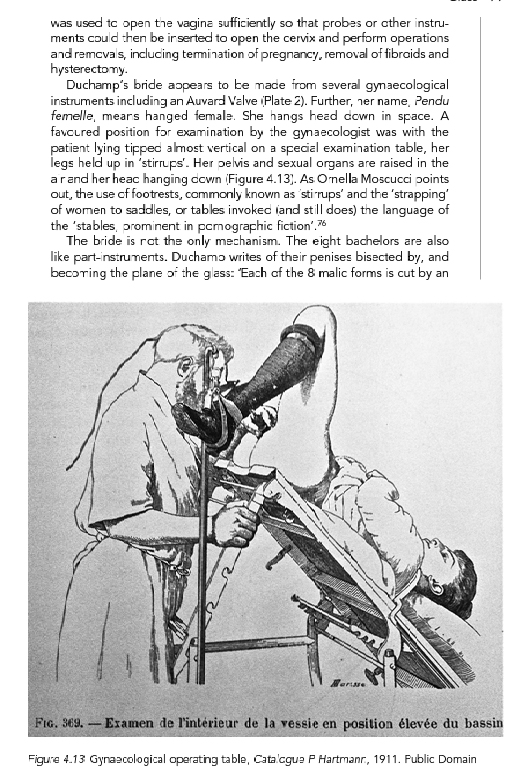

I had been working with the occasional article from medical anthropology or science studies, but it was only more recently that I realized there is this emerging field of scholarship called the “critical medical humanities”, a fascinating research area that allows for many different methodologies and interdisciplinary conversations. Now I read a lot of history of medicine, history of science and technology and social history scholarship for my PhD research at the Royal College of Art in London, for which I’m working across and between objects from the histories of women’s healthcare that are held in the Wellcome Collection and contemporary artworks in the Birth Rites Collection, a unique collection on the theme of birth and maternity. I still sometimes feel like a tourist in the medical humanities, but I find it really exciting to apply the visual research methods and artistic approaches that are natural to me to work across these fields.

Allison Morehead, Fiona Johnstone, and Imogen Wiltshire who convened the Confabulations series that hosted Being Horizontal are all art historians who have been working with the critical medical humanities for a much longer time than me. They specifically designed Confabulations to bring together conversations around health and care from art practice, art history, and the medical humanities, so this felt like a perfect context for this event and a nice way to connect with the medical humanities community.

In fact, Being Horizontal was originally an exhibition proposal, which I reworked into an online event for Confabulations. I’m still pursuing this research and hoping to make an exhibition eventually, in which sculpture, installation, artist film, drawings, and photography are in conversation with a growing collection of images relating to the history of healthcare that I keep in a folder on my computer…

Whilst it always felt a bit weird to attend events during the pandemic, there is an added value to watch this at home now. I guess this was intended?

All the events in the Confabulations series are streamed online and this evening, too, was designed specifically for the Zoom format. It lends itself very well to curated film screenings, especially relatively short films, although of course I can’t control the size and quality of the screen and the sound as I could in an exhibition or in-person event. But I felt that the intimacy of participating in this event from home, perhaps with family members or flatmates, suited the concerns of the evening. In my short opening address, I invited my audience to make themselves comfortable, perhaps on the sofa, a yoga mat, or in bed, and to have drinks and snacks. It was intended as a stimulating, but also a relaxed and entertaining evening.

Online events have many advantages: they can be enjoyed by an international audience and by people who can’t easily get to cultural venues or are avoiding large gatherings. Although it was a little complicated to sort out the permissions for all three films, we decided it was important to record the event and make it available on the Confabulations page for a few weeks. This way, people who couldn’t attend that evening, for example because they had to put children to bed or were in another time zone, still had access to the event.

It was interesting for me to curate an online event (it’s a lot more work that it seems!) and I think it has many advantages but should be considered on its own terms rather than as an equivalent of an in-person gathering.