Language and Civilization

Language as a tool of cultural assimilation and creation of dominant orders of power

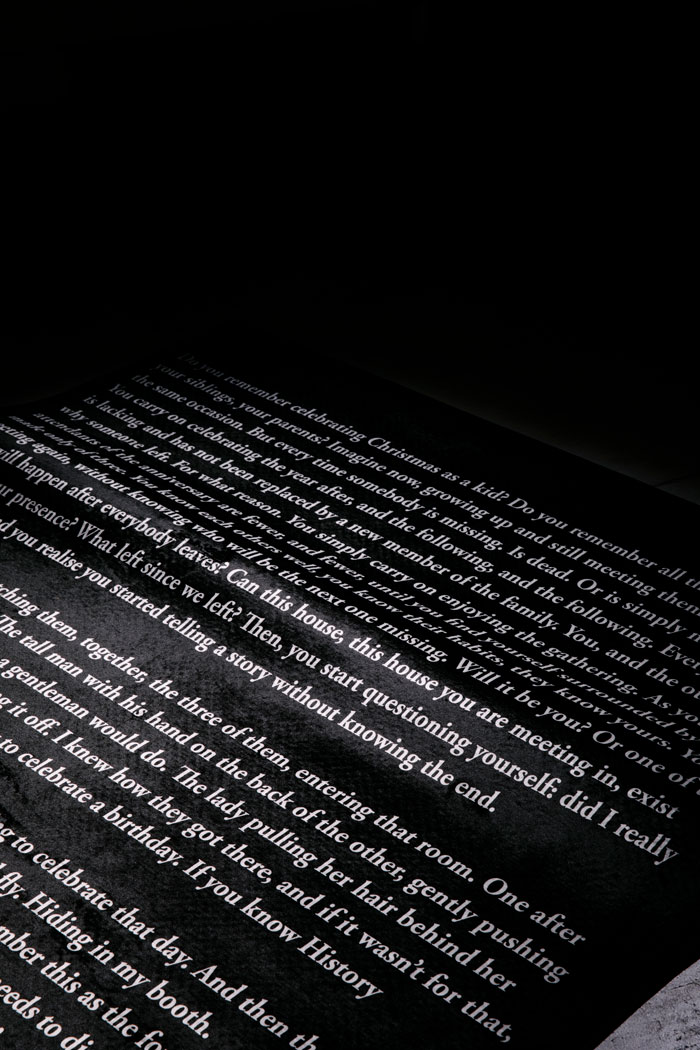

Curated by Marta Cereda, Giulio Squillacciotti’s exhibition project What Has Left Since We Left questions the value and meaning of European identity, the linguistic issue, the apparently marginal roles in significant historical moments. The project talks about collapse, migration, conflict, hope, it discusses points of view, neutrality, distortion, impartiality, translations and addresses inheritance, separation, abandonment, divorce.

“I’m not sure how to interpret all this” – Amalia The Interpreter

In Giulio Squillacciotti’s What Has Left Since We Left? (2020) the character of the interpreter opens the film’s dialogue in recognizable British English. She makes a sarcastic comment on the futility of her task.

“Wonder is the first step into the wonders of interpretation” – The Interpreter

Language is a way of thinking. In 1922, Wittgenstein’s famous quote “die Grenzen meiner Sprache bedeuten die Grenzer meiner Welt” was published in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. [1] The idea that language conditions a way of thinking and defines limits of logic and analysis can be found in how language reflects cultural values across the world. Language is inherently connected to identity as well as to the possibility of forming communities of shared values and mutual intelligibility. Its exact meaning is inherently untranslatable. It is a practical tool, but also one that is political and ideological in nature.

Historically, language has been a tool of cultural assimilation and the creation of dominant orders of power. Political and religious language was often different from local tongues and was used as a form of class distinction. [2] Today’s romance languages were created by the imposition of Latin as an administrative and military tool during the Roman Empire. Even once regional variation became dominant with the emergence of various languages, Latin remained the de-facto intellectual and political tongue for centuries to come. The European aristocracy of the middle age set their values on Christianity and the Church in Rome. Today, the European Union intends to address the difference between vernacular and official communication by including 24 official languages in white papers, debates, and interpretation. Yet, Europe is home to over 60 indigenous and minority languages spoken by millions of its citizens. Even with the claim of defending “linguistic diversity,” the power to decide on who is made official in the bulletins of the European Union is left to its member states, who are often far from neutral.

The interpreter knows she embodies a reminder of painful separation. Her language is a vessel through which the politicians chat, quarrel, and deliberate in the tongue which is an echo of their first divorce—the UK. In post-Brexit Europe, English remains an official and popular language for European debate due to its co-official linguistic status in the member states of Ireland and Malta. Yet we know that languages are nothing but neutral. Which languages dominate are closely related to history, power and ideology, and English is no exception.

In 2017, the European Union offered a set of 5 possible scenarios for the Future of Europe in the wake of Brexit. One of the options offered was “nothing but the single market” referencing the unresolvable differences of opinion between member states that often led to prolonged and difficult resolution processes. [3] In the post-Brexit scenario the English language remains the first language that greets you on any EU website and the most frequently used, it is the de-facto language of global capitalism. The history of how English gained this global status is the accentuation of market values and values that all countries in the European Union can understand—their own economic benefit.

Economy in the West is inextricably connected to the ongoing colonial structure of economic power, and language has been one of the weapons of imperial conquest. In the colonial age language, along with religion, was deployed in “civilizing” missions and produced the loss of linguistic diversity which can never be retrieved. [4] If this strategy was projected outwards towards colonies in the 17th century, it would later be mirrored within the European territory due to the rise of the nation-state. [5]

Until the 19th century the languages and dialects of Europe showed strong regional variation. But the lack of codification and immense variation did not stop traders or merchants from being able to communicate with large amounts of people. In fact, linguistic diversity helped people to understand foreign languages and dialects through constant exposure to different grammatic forms and gradual changes through territory. The entire Western Mediterranean spoke in different ways, but they were so similar that they were mutually intelligible from Northern Italian dialects, to Occitan (now nearly extinct), to Catalan, to Portuguese. In Catalan, the connection of language to the sea is so strong that it is the only noun that is equally male and female: el mar and la mar are both equally grammatically correct. Furthermore, for sailors who traveled the entire waters of the Mediterranean, the process of creolization produced a unique pidgin-language that belonged not to a landed territory but to the inhabitants of ships, a language of the sea.

From the 11th to the 19th century the Mediterranean Sea was an entity of connectivity, not of separation. Southern France was more connected to North Africa than to Paris. [6] This context led to the emergence of Sabir (to know: Saber, Sapere, Ssen). It was the lingua-Franca of the Mediterranean region and combined words and grammar from multiple Italian dialects, Occitan, Catalan, Berber languages, Arabic, and Turkish among others. [7] Sailors would greet each other by asking: Sabir? And if their interlocutor understood they would respond: Sabir. A language such as Sabir, which was in a constant state of flux, without defined grammar, as liquid as the waters on which it thrived—was a product of a Mediterranean fluidity that connected port cities to create thriving economies away from the ideology of terracentrism. [8] The Mediterranean civilization was one that looked outwards and was able to fuse cultures spread over vast areas rather than look inwards towards the land. Borders do not float on water.

In the 19th century Sabir lost its purpose. The final colonial land-grabs of North Africa and the Levant had been completed and a hierarchy of value shifted language relations in the region. Sabir was replaced by French. It was the century of “national awakenings” when many languages were written down in official measures of grammar and vocabulary for the first time. The creation of official languages was a product of the nation-state attempting to legitimize itself and would ultimately produce the independence of states in Eastern Europe just after the turn of the century, and the elimination and suppression of minority languages in Western Europe. The French and German economic powerhouses of states became more linguistically universal, until they were overcome by a language whose own history as an ex-colony and capitalist success story made it emerge as a new colonial power, the United States. The implementation of English as the de-facto language of global capitalism was implemented in the entrenchment of a cold war that championed the capitalist economic system without any alternative. Only the single-market.

Today, the European Union accepts linguistic diversity as defined within the ideology of the nation-state. Only those languages proposed by member states are accepted. Under the guise of protection of diversity, the linguistic aspiration of the Union responds only to bureaucratic force. Who protects the over 60 indigenous and minority languages of Europe? Each year other languages grow in use within the European territory including Turkish, Arabic, and Russian. But no matter how many speakers, these languages will remain unimaginable inclusions to the list of official languages of the European Union.

“Someone to blame for what I don’t dare to recognize as part of myself.” – Lucas (Through the Interpreter’s Headphones)

Slowly, the three remaining members in the film throw off their act. They switch to English and speak more fluidly with each other. The symbolic role of the interpreter is revealed, she begins to act as a therapist, guiding the session rather than passively interpreting. She is a medium, a vessel that tells them what to say before they’ve had time to think of it themselves. The interpreter is the only one here with any power at all. In the moment of the switch to English is the mention of what holds them together—mutual security, and mutual profit. [9]

The problems of these characters emerge as banal stories of love, loss, family. They are allegories of the complex relations between nations and the extra-national structure of Europe. They are testaments to the fact that institutions are people. As time goes on the characters discuss scenarios in which ethics and ideals are brushed aside in the name of profit, episodes of shame, embarrassment, self-loathing and hatred of the other. What holds us together? They ask. With a noted look of sarcasm, Lucas pronounces:

“Liberty, Franternité, Freiheit?”

“We made it possible for them to speak their own language, to speak their mind, and still be understood.” – The Interpreter

[1] Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 1921

[2] After the Norman Conquest of England both the nobility and the church recorded documents in languages that most of the English population could not understand. The political elite recorded texts in French while the Church recorded bibles and gave sermons in Latin. Over much of Europe illiterate working populations attended masses they could not understand leading to the development of pictorial representations and stained glass. Manuscripts and Special Collections Nottingham University Poor Man’s Bible, New World Encyclopedia

[3] White Paper on the Future of Europe: Reflections and Scenarios for the EU 27 by 2025 1, March 2017.

[4] “All parties seem to be agreed on one point, that the dialects commonly spoken among the natives of this part of India contain neither Literary nor scientific information, and are, moreover, so poor and rude that, until they are enriched from some other quarter, it will not be easy to translate any valuable work into them. It seems to be admitted on all sides that the intellectual improvement of those classes of the people who have the means of pursuing higher studies can at present be effect only by means of some language not vernacular amongst them.” Thomas Babington Macaulay, Civilizing Mission 1835.

[5] As the idea of “nations” was increasingly defined by ethnic communities and belonging, minority languages began to be seen as a threat to the unity of imperial military states such as the case of Iberia. John E. Joseph, Language, Politics, and the Nation-State, University of Edinburgh.

[6] Although this history is largely obscured in official histories, recent artistic and archeological projects have been attempting to unearth the deep connections between ports like Marseille and North African Populations. For instance: Sara Ouhaddou, Le Port: À la croisée des Histoires, Manifesta 13 Marseille, 2020.

[7] Roberto Rosetti, An Introduction to Lingua-Franca

[8] Terracentrism is a concept developed to contrast with contemporary land-based notions of identity and reclaim the importance of the non-national territories, their social constructions and hierarchies, in the modern conception of world history. Ie. Rila Mukherjee, Escape from Terracentrism, Ecole des Hautes Etudes, Paris, 2014.

[9] Giulio Squillacciotti, What Has Left Since we Left?, 2020. 07:10-07:15