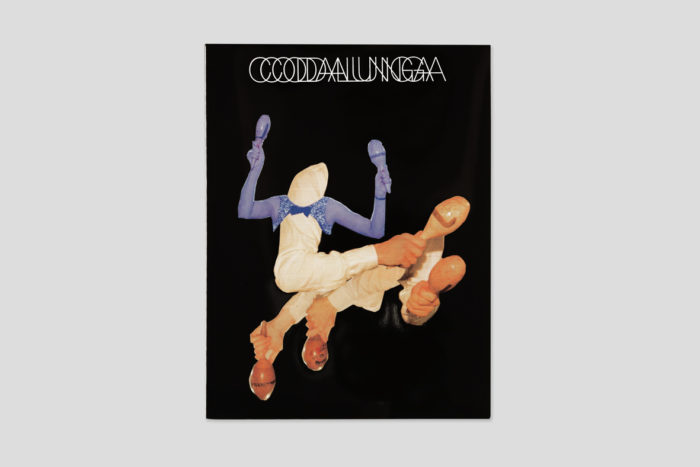

King of Shit

How Nico Vascellari turned a small venue in a forgotten Italian town into an international crossroad for artists and musicians

The article Nico Vascellari—L’effetto è più grande della somma delle parti originally appeared on Flash Art 286, August–September 2010, and what follows is an excerpt from the book Codalunga (NERO, 2018). Courtesy Flash Art

Revisiting this text, written together exactly eight years ago, we realized our mistake. Despite being called “The effect is larger than the sum of its parts,” we largely limit ourselves to analyze the single works made by Nico Vascellari between 2004 and 2010. We therefore neglected the gravitational heart around which his artistic practice, his activity as a musician and his desire to work together with other people had started to revolve from those last years onwards.

Maybe it was still too early to consider it, maybe it was still a space too charged with young emotions to be placed in a theoretical/critical frame and maybe we were actually aiming at giving consistence to the major single works instead of falling within an emotional trap that risked to condition a dense career punctuated by important works. Or maybe we simply needed this temporal gap to understand that the effect that named this article was nothing more than Codalunga: a project that became a place, a community, a world, and whose results are certainly greater than the sum of its parts.

The world has changed radically during these eight years. The optimism and energy that we find in these lines struggle to emerge now, more for the changes in the political-social-environmental-emotional scenario around us than for an ageing condition. Likewise, Codalunga also changed. One of its latest creations is a t-shirt that has the correspondence of letters between DREAM and MERDA [SHIT], one atop the other. From dream we arrive to shit, in a more cynical and pessimistic vision than the joyful nihilism of the first years of Codalunga. But there are no mandatory directions, nor a true linearity: the movement is reciprocal and from shit restart towards dream. As in Nico’s entire work, there’s a splendid tension between the below and the above and one incessantly feeds the other.

Therefore, at the end, in its vibration and constant process of becoming, Codalunga reminds us that transformation is perennial and, above all, fantastically unpredictable.

After what seemed to be the closure of an important phase, articulated around four fundamental exhibitions—Cuckoo (Viafarini, Milan, 2006), Revenge (Venice Biennale, 2007), Untitled (Mamoiada) (MAN Museum, Nuoro, 2007–2008), and Hymn (Manifesta 7, Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol, 2008)—we wondered where Nico Vascellari’s work was heading to. Those projects composed a cycle that consecrated him as one of the most solid artists of his generation, able of creating minimal interventions based on his presence and gestures and of facing large spaces with surprising works. But how to communicate the impressions of these gestures in which the essential can’t be seen and instead what is visible is so majestic and monumental that it shadows narratives and sensations?

It was clear to us that something had changed after those four moments in his recent past. Despite their diversity, those works constituted a quasi-mythological character whose inception was at the performative saga A Great Circle (2003–2004). This character reached its apex in Revenge to announce the beginning of its gradual transformation in Hymn, a work already signed by the absence of this charismatic figure. Those early auguries of transformation and dissolution confirmed themselves: Vascellari is now a different artist than he was some years ago and it’s this transformative—or evolutionary—process that we want to interrogate.

Beyond the development of a careful mise-en-scène of precise rituals (despite the constant presence of improvisation, attesting a form of non-linear, uncontrolled intelligence, close to the noise musical tradition from which he belongs), the fundamental element of that cycle was the character of the artist, each time introduced as a mythic figure, complemented with dramatic attributes (clothes, pendants, staffs, heavy hooded mantles…), frequently surrounded by a clan of faithful and loyal assistants. But already in I Hear a Shadow (Lambretto Art Project, Milan, 2009), that figure was giving way to something else. The work consisted of a monumental bronze sculpture made from the cast of a block of marble extracted from a mountain. In the dark, Vascellari a-rhythmically banged a beam against the sculpture. Testing, examining and playing it to the exhaustion of his forces. A hooded character illuminated his steps around this strange bell. Also in the darkness, four cronies manipulated the sounds that came from the amplified bronze.

A subsequent aspect that seems to emerge is the construction of what could be defined as a dialogue with a metric structure. Both in I Hear a Shadow and Gnawing My Own Teeth behind a Closed Door (Manchester International Festival, 2009), the performance produced a sound signed by a precise, almost maniac rhythmic regime. A beat with deep percussions that originated from the noise-punk musical tradition in which the voice of the artist or his gestures with the microphone produced a direct feedback and cutting, manipulated sounds, re-worked or amplified live by other musicians (John Wiese, Stephen O’Malley, Ottaven…). What arose in I Hear a Shadow and was consolidated in Gnawing My Own Teeth behind a Closed Door was the time of the work: the conscious construction of its duration, the constitution of a structure. Not evolving on the dramaturgic field, the performance was pushed towards exhaustion.

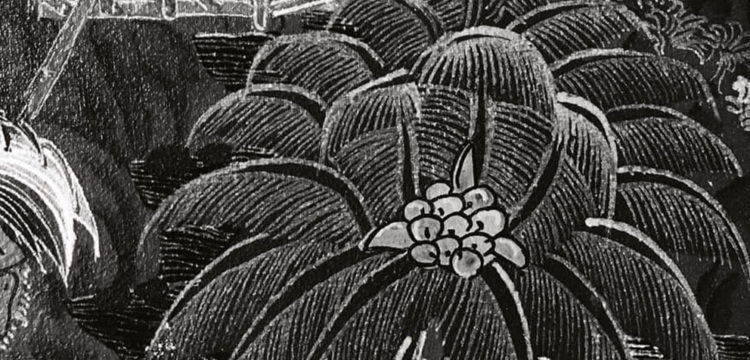

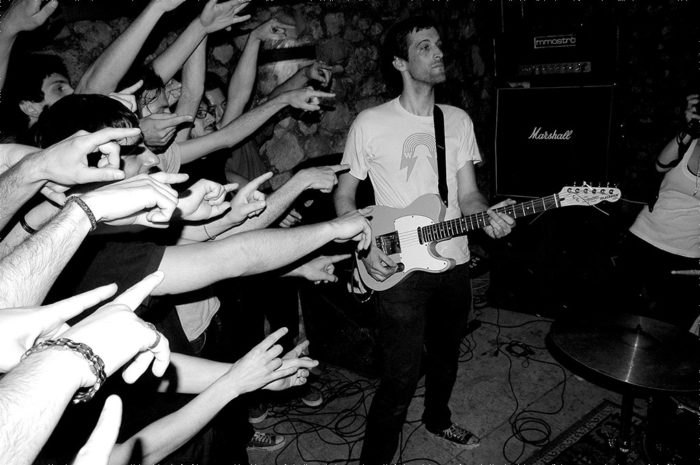

One word characterizes what has been Lago Morto (Vittorio Veneto, 2009): “hardcore.” This concept defines the most engaged, active and orthodox side of the members of a group but also that music, experimental by nature, defined by high volumes and an aggressive presentation. Lago Morto was an intensive project for which the artist gathered the members of the homonymous band and every day, during two consecutive weeks in May, they gave a series of concerts in various locations of the small town of Vittorio Veneto—a restaurant, a laundromat, a pizzeria, a video rental… Daily repetition of a collective, spontaneous and liberated gesture, Lago Morto was more than a mere tour of a band in a Veneto location. The remains of these actions were reworked and became a mix that in its confusion and dispersion relaunched the spirit of the performances.

As in the other performative projects, Lago Morto can’t be narrated. Words would turn it into a juvenile rebellion act devoid of meaning. You had to be there to experience the energy and intensity of one of the most impressive artistic events of 2009: due to its intimate dimension but first and foremost to its generosity and passion. And if hardcore defines Lago Morto, it’s the title of Vascellari’s old noise-punk band that characterizes its spirit: With Love indeed conveys what was lived in Vittorio Veneto during those days—pure, radical, raw and unconditioned love.

Following that explosion of feelings and regressive adventures, Nico Vascellari re-entered a new period of intensive labor, this time on his own and away from his domestic rebellion. He did so in the crude, post-industrial landscape of that city which stands for the triumph and decadence of the alienating and entertaining possibilities of the musical scene of the 1990s: Manchester. The action took place in the Victorian Whitworth Art Gallery during the Manchester Festival in July 2009. Once more, narrative fails to convey what happened there, mainly because we’d like to focus on its sound and rhythm. The visit to the survey of performances was signed by the almost annoying sound of a piece of metal being hit with a slow, constant but changing cadence, which bore the trace of a human intervention. There were no evidences of the origin of that sound. The more stubborn visitors would have discovered that one of the service doors of the museum gave way to a staircase under which, in the dark, almost hidden, without clothes nor ritual, Vascellari executed the constant action of hammering a rock against a metal block (a rock collected in a forest and its brass cast, obtained from the melting of cow bells). In Gnawing My Own Teeth behind a Closed Door, the artist, for twenty consecutive days, repeated that same desperate gesture until he pulverized the stone. He was a lost soul, a condemned who atoned for an eternal punishment.

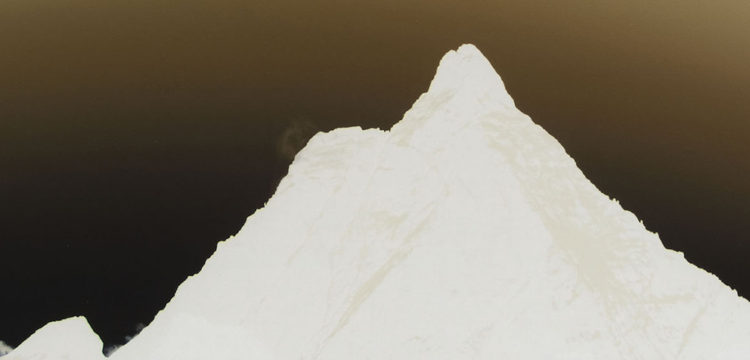

Between December 2009 and January 2010, in one of the harshest and hostile winters of the last years, Nico Vascellari was invited to do a residency at Perarolo di Cadore, a town of about 300 inhabitants which had the fortune—or misfortune—of remaining cut out of any industrial and touristic development. There, the artist staged his own death (Untitled, 2009), tattooing himself a tombstone with the writing “2009,” and then building a transparent coffin made of metal and glass which he filled with snow. Inevitably melting, the snow had a microphone inside it, which emitted its sound to the entire village, as if it were a funeral to a body already dematerialized of which the sole remain is pure sound and rhythm. And, naturally, the experience of those who were there.