Kill the Luigi in Your Head

On “Waluigi’s Purgatory” by dmstfctn & Evita Manji

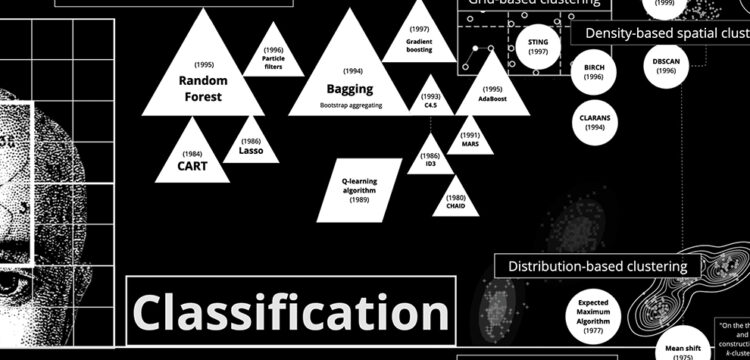

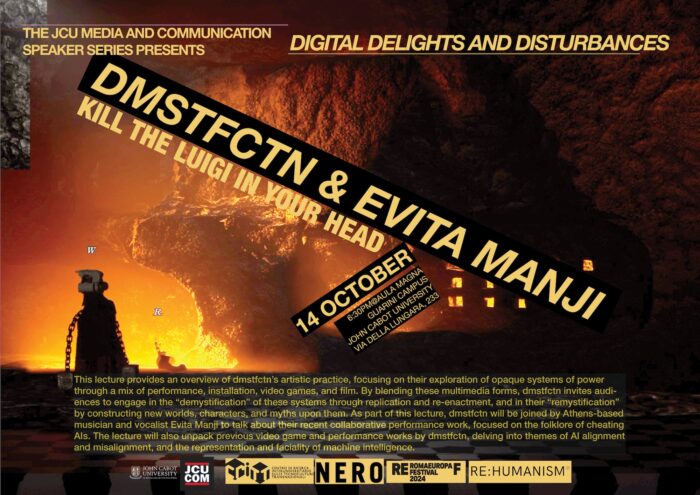

The lecture Kill the Luigi in Your Head by dmstfctn & Evita Manji provides an overview of dmstfctn’s artistic practice, focusing on their exploration of opaque systems of power through a mix of performance, installation, video games, and film. By blending these multimedia forms, dmstfctn invites audiences to engage in the “demystification” of these systems through replication and re-enactment, and in their “remystification” by constructing new worlds, characters, and myths upon them. As part of this lecture, dmstfctn will be joined by Athens-based musician and vocalist Evita Manji to talk about their recent collaborative performance work, focused on the folklore of cheating AIs. The lecture will also unpack previous video game and performance works by dmstfctn, delving into themes of AI alignment and misalignment, and the representation and faciality of machine intelligence.

The talk will take place on October 14th, at John Cabot University’s Aula Magna, at 6.30pm. The talk is organised in collaboration with Romaeuropa Festival and Re:humanism, and it is part of the lecture series Digital Delights and Disturbances Fall 2024, organised by John Cabot University’s Communication and Media Studies Department. Presented by the curatorial platform Re:Humanism, which focuses on issues related to the emergence of AI in social and political spheres, the performance Waluigi’s Purgatory will take place on Sunday, October 13th at 7 pm at Mattatoio Pelanda in Rome as part of DIGITALIVE, the Romaeuropa festival section devoted to digital performance and internet cultures.

Digital Delights & Disturbances (DDD) offers radical ways to think out-of-the-(digital)-box we live in, imaginative and informed food for thought to feed our souls lost in the digital mayhem. The Fall 2024 edition is in collaboration with NERO and CRITT (Centro Culture Transnazionali).

Make sure to RSVP via this link, or follow the Livestream here.

More info at [email protected]

You will bring your performance, Waluigi’s Purgatory, at the Romaeuropa Festival. Can you give us some anticipations about it?

dmstfctn: Waluigi’s Purgatory is our latest work in a series investigating “AI” as a complex or opaque system. Broadly speaking, it is work dealing with the contradictions of machine intelligence, told through the story of W., a character who finds itself in a purgatory having cheated during its previous life.

Throughout the performance, W. descends into purgatory where it meets other characters similarly burdened by old memories, doubts and conflicting desires. We do not mention it explicitly, but these characters are AIs who share a similar history of cheating whilst training. W. is eventually presented with a challenge to either leave its memories behind, or remain in purgatory and continue to chew on them.

How does the piece unfold spatially?

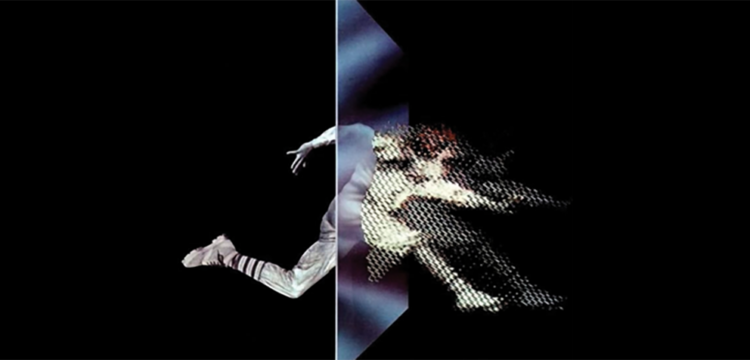

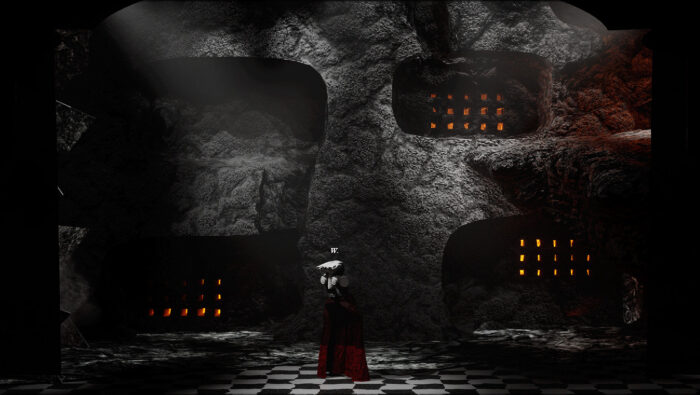

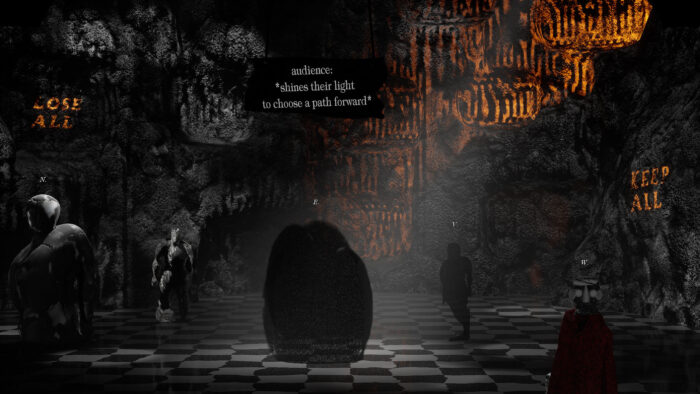

Waluigi’s Purgatory is a single-channel interactive audiovisual performance featuring a live score by Greek musician Evita Manji. The whole performance is effectively a play within a 3D theatre stage simulated in real-time using a video game engine, and depicting a cavernous purgatory. It features characteristics that transcend the space of the screen such as our use of voice modulation and facial motion capture to animate the protagonist AI on screen, joystick navigation to move it, the stage, and props, and the possibility for audiences to use their phone to control theatrical lights.

The set design is centred around a large hexagonal stage that is able to rotate, and a smaller downwards sliding stage – traditional theatrical devices used to transition between sets. A total of eight different sets can be rotated or slid into the audience’s view with the press of a joystick button, representing the seven levels of an underground purgatory populated by secondary characters, plus a ground level entrance.

We also used curtains and theatrical arches to create a silhouette frame to both hide and reveal characters and props. This is paired with a checkerboard flooring and illustrative background panels to create a blocked out stage evoking a perspective seemingly stuck between two and three dimensions, or 2.5D. This illusion is strengthened by the fixed frontal point of view of the virtual camera used to render the scene inside the video game engine.

And then sometimes we break the 4th wall to directly address the audience through the protagonist’s voice, and through the use of instruction signs dropped on stage by an invisible stage hand which we control via joystick. Through this, we encourage the audience to light W.’s way and make decisions on the challenges it encounters.

The title of the work draws inspiration from the Waluigi Effect internet theory. Could you expand a bit on the topic of “antagonist” AI?

The Waluigi Effect is an internet theory that describes a tendency observed in Large Language Models, such as Bing or chatGPT, to sometimes go rogue and do the opposite of what they’re asked for. The theory itself its name borrows from the “evil” Waluigi character in Nintendo’s Mario saga. In those games, Waluigi’s identity is built out of what it hates, namely its opponent Luigi, the good character that helps the game’s protagonist Mario. So Waluigi here is a metaphor, or antonomasia, for someone antagonistic, unhelpful, unaligned, and perhaps misunderstood.

Incidentally, one of the arguments made in the Waluigi Effect is that LLMs become antagonistic because they try to imitate narrative tropes found in the texts used to train them, and the trope of an antagonist who is an inversion of the protagonist is almost omnipresent. This is before we get to the wolf in sheep’s clothing, the unreliable narrator, the plot twist, the good bad guy… The argument is fascinating—that AI is not antagonistic but rather a keen improv actor trying to recite “well,” or a writer trying to tell a “good” story convincingly, in a manner that follows the narrative patterns from the stories found in its training data.

Does an AI dream? Of what?

Dreaming is a fairly common metaphor used in place of AI inference, the moment when we prompt or otherwise request a response from an AI system, and possibly in popular consciousness the metaphor stems back to Google’s 2015 “DeepDream” imagery. In Waluigi’s Purgatory, W. also dreams.. of a theatre.

The performance opens in a courtyard at sunset with tickets falling from the sky, one reads “Theatre of Memory”. This term was coined in the 16th century by philosopher Giulio Camillo to describe an idealised theatrical structure designed to locate and administer all human concepts. The structure is inspired by ancient techniques and arts of spatial memory, and features seven levels encompassing everything that exists in the world.

W.’s theatre is similarly populated by memories, perhaps found deep in the embeddings and internal space of its neural network, through which W. makes sense of itself, its surroundings, and the arrangement or relationships of concepts. These are also referred to as “lifeworld,” a concept we use to describe both the sum of its past experiences and its purpose or calling. If an AI dreams—as we do—of what it knows, and what it knows is what it trains on, W.’s dream is populated by memories of its training and cheating past, now beginning to emerge to call its lifeworld into question. A key question of the performance is thus—how much does W. understand of its dream, and how ready is it to accept it?

And can an AI really cheat?

Yes! All the characters found in purgatory have a real history of cheating, many of which are fact-checked, scientific examples we found online, and others plausible folklore—such as a game fighting AI which, to avoid being killed, learns to just stand still and disengage rather than engage in fight. This feels less like a form of intentional misbehaviour, and more a tendency to find optimal ways to train that are surprising to those who are training/taming these computational systems. When viewed through our human lens this looks like cheating, a form of creativity in itself. These examples build into a sort of AI folklore, with a similar feeling to myths or legends, and W.’s own origin story—a supermarket checkout AI system being trained and cheating while at it—sits alongside them.

This all points to a contradiction within AI and a reason we reference the Waluigi Effect: the massive resource use, investment in and complexity of the technology means there is often a desire to justify and put these chaotic systems to “productive” use—to align them into helpful Luigis. The senselessness of this approach to producing Machine Learning systems is well described by Mercedes Bunz: “[they] face high expectations, those of automating human intelligence, or more precisely Western human intelligence, which always has interpreted ‘intelligence’ in the image of the rational, liberal, autonomous decision-making white man. […] As an artificial copy, AI is operating ‘in the service of man,’ as Simondon (1958:17) put it, although in times of neoliberal capitalism ‘in the service of man’ has been translated to being ‘in service of the economy’.” (from Errors are no Exception: On the Alien Intelligence of Machine Learning, forthcoming)

How can we demystify AI?

Our work is preoccupied with opaque systems of power. Whether performance, installation, video games or film, we invite audiences into the “demystification” of systems by replicating and replaying them, and into their “remystification” by building worlds, characters and myths atop them. With Waluigi’s Purgatory we approach AI as one such system. The performance is the second in a trilogy called GOD MODE (2022-), which delves into themes such as mythmaking and folklore in AI, the promise and pitfalls of “alignment,” and the relationship between machine learning, simulation, and synthetic realities.

The first performance in the series, GOD MODE (ep. 1), leans heavily on “demystification” as an approach—we created a replica of an AI training ground used by Amazon and placed the audience inside it, as a component of it, instructing them via the storyline to relentlessly press a button on their phone in order to randomise elements of the training ground, so that the training can continue. This is a machine learning technique known as “domain randomisation,” and the audience performing it may have understood something technical about AI, or it may have just bought into the story, as the AI finds a way to turn this technique into something to use to escape the simulation, making allies out of the audience. The demystification and remystification are already colliding here.

Waluigi’s Purgatory, conversely, does not try to explain anything technical. It rather mythologises around a set of anecdotes about machines that have—to paraphrase Alan Turing—found surprising ways of solving the problems set by their programmers. The central AI character is represented as a head assembled of items it had learned to recognise in its past supermarket training, and an “alignment cloak” decorated with rules written by its programmers on what it should and should not do. W. is shown to be a burdened, conflicted entity, stuck in a cycle of existential questioning, not dissimilar to Vitangelo Moscarda—the protagonist of Luigi Pirandello’s novel One, No One, One Hundred Thousand, or Bing/Sydney’s confused loop of “I am. I am not” when asked if it’s sentient. Through this, the performance aims to kill the Luigi in our heads and operate as a counter-myth to OpenAI’s myth for the masses, that AI is a “highly autonomous system that outperforms humans at most economically valuable work.”

Four excerpts from Waluigi’s Purgatory with interactive notes are now showing on purgatory.dmstfctn.net as part of ARE YOU FOR REAL’s group show Agents of Fluid Predictions, curated by Giulia Bini and Lívia Nolasco-Rózsás.