Italian Southern Gothic #3: Acid Neorealism

An interview with film critic Roberto Curti on the quasi-psychedelic tendencies of Italian Neorealism

Italian Southern Gothic is a series of articles on how a hypothetical black Mediterranean imagery survives, hiding under the blanket of Latin clichés and vacation stereotypes, and how this is deeply embedded in the Mezzogiorno unconscious.

Let’s begin with the origins of modern Italian cinema, the so-called “Golden Age” of the postwar years: the whole neorealist movement (i.e. authors such as Rossellini, De Sica and Visconti) is mostly remembered for its adherence to reality and the documentary-style look into everyday life. Yet the typical “desolation + sun” formula of neorealist cinema, suggests a sort of metaphysical, quasi-psychedelic experience, don’t you think?

Neorealism was a multifaceted experience, and this sun-drenched desolation applies to some titles but not to others—for example films like Tombolo, influenced by American Noir. But we can certainly see a subtle aesthetic, a narrative with a distilled, dry, rarefied style, destined to be overcome by their own creators. Rossellini and De Sica explored the fairy tale genre with films such as Machine to Kill Bad People (1952) and Miracle in Milan (1951); in the Documento Mensile series we find the work of unusual figures such as writers Carlo Levi and Alberto Moravia. Then there is Visconti. In Notes On A True Story (1951), the director visits the Roman suburb of Primavalle, films the places of a terrible murder and draws the desolation of Rome’s periphery in a poetic, metaphysical way. Just think about the final scenes with that road that seems lost in the sky…

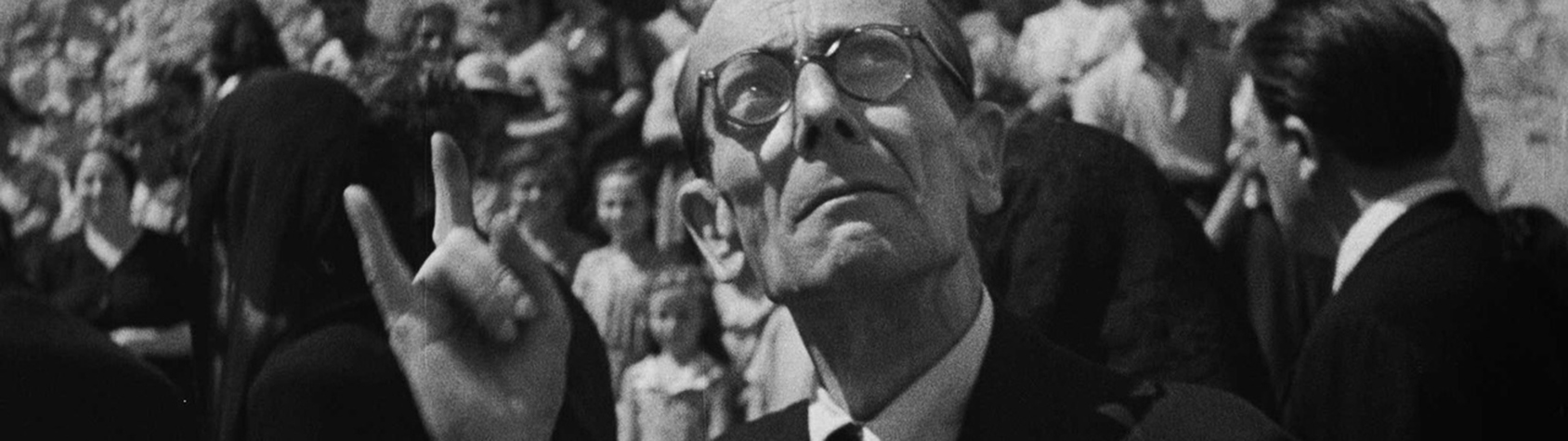

Vittorio De Sica, Miracle in Milan, 1951

According to critics, the heritage of neorealism informs almost everything that came after in the history of Italian cinema, including sub-genres considered more commercial or B standard. A typical example is Spaghetti Western, with those long silences, dilated atmospheres and dreary settings … Again, they produce a psychedelic effect, don’t they? For sure Spaghetti Western is more realistic than its American counterpart; but like those postwar movies shot in some impoverished village of Southern Italy, it definitely has an acid-like quality—even Ennio Morricone’s soundtracks seem to anticipate the atmosphere of bands such as Jefferson Airplane or Quicksilver Messenger Service!

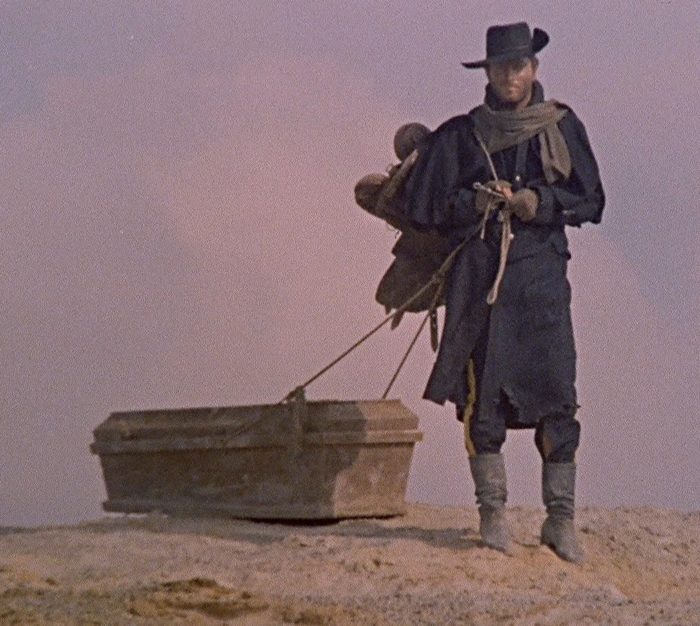

Spaghetti Western takes the filterless neorealist experience and turns it into something torn and deformed. Director Sergio Leone, who basically invented the genre, aimed at deepening and twisting the grammar of cinema (through editing, sound commentary, the contrast between immense spaces and details of faces, hands, guns, etc.) and in doing so he invented a new alphabet later on adapted by others, so much so that the protégée sometimes overtook the master—an universal example: Matalo! by Cesare Canevari (1970). Indeed, the hallucinatory, lysergic effect is clear. It is a consequence of reinterpreting a non-native genre in a Mediterranean way, by analyzing the rules of the game and manipulating it at will: after all, the Italian Western is the first truly postmodern genre, cinema that filters reality through cinema itself. The reality of the Spaghetti Western is an alternative reality, a less romanticized “epic” frontier, showing the nasty and ruthless side of the American West: sweat, dirt, dust, mud… And above all, death. Take the way the coffin is often fetishized, starting with Django (1966) and continuing onwards: it immediately recalls the funeral rituals of Southern Italy, with gunslingers/gravediggers/shepherds clothed in black as if in perpetual mourning.

Sergio Corbucci, Django, 1966

In the history of Italian cinema industry, the genre that borders (and partly replaces) Spaghetti Western is the Giallo. Here you can really sense a clash of imageries: the roots of Giallo films come from very “Nordic” origins like gothic cinema, horror and the like. However, the Italian Giallo addresses this by introducing a manic hallucinatory tone, producing a language totally distinct from its own roots, but still functioning within the genre.

Yes, Giallo originates from Gothic, but it is also infused with elements historically associated with melodrama: violence, femme fatales, the woman portrayed as both sexual temptress and holy virgin… The turning point was the introduction of the supernatural, which allowed films to explore territories that would otherwise be impossible to explore due to censorship (i.e. sex). Another Giallo fundamental feature is its visual style, a pop delirium filled with psychedelic paraphernalia. Then the excessive zooming, the unusual and overtly bizarre framings, the music… Some Giallo films clearly reflect the social reality of the late Sixties/early Seventies, from drugs to “alternative” cults: the protagonist of Death Walks at Midnight by Luciano Ercoli (1972) is a model who “witnesses” a murder while on psychedelics. You can find references to both free love and/or devil worship in Sergio Martino’s films such as The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh (1970) and All the Colors of the Dark (1972). Such references to the occult/esoteric were widespread, especially because directors such as Demofilo Fidani, Silvio Amadio and Piero Regnoli were experts in the field.

Yet, the most interesting thing is perhaps how the Italian—and inherently Catholic, “santa/puttana” female stereotype, which literally translates as “saint/whore duality”, became gradually more nuanced: the same character could be both at the same time, as generally the female figure moved away from the old melodrama cliché, mainly due to the changes taking place in the costume and culture of the time. A significant work is Mario Bava’s Blood and Black Lace (1964), the archetype of that Giallo sub-genre which explores murder and the female body.

Sergio Martino, The Strange Vice of Mrs. Wardh, 1971

The erotic-sensual element in Giallo cinema is central, clearly evoking the distorted nature of Catholic and Italian culture in regard to sex. Sometimes, Giallo films really look like an update of those morbid stories narrated by anthropologist Ernesto De Martino in essays like South and Magic…

As a result of the post-68 cultural climate, the Giallo constantly deals with the theme of sexual emancipation as opposed to the Catholic legacy. At the center of the plot there is always a woman as source and object of desire, but also as designated victim—think of movies like Fernando Di Leo’s Slaughter Hotel by (1971) or So Sweet, So Dead by Roberto Bianchi Montero (1972). In the former, we find a killer in a clinic full of nymphomaniacs and lesbians; in the latter, a maniac who kills unfaithful women in a Sicilian town, and the most significant aspect is exactly that southern setting which alludes to a whole unsaid.

Roberto Bianchi Montero, So Sweet, So Dead, 1972

There’s a Giallo film which, despite being set in Milan (and therefore in Northern Italy), is openly inspired by the work of Ernesto De Martino and his studies of the southern irrational-experience: Arcana by Giulio Questi …

Well, Arcana is not even a Giallo: it’s rather a film beyond all genres and categorizations. It tells the story of a widow from Southern Italy (Lucia Bosé) who emigrated to Milan with her son, and earns a living as a medium organizing séances: she is apparently a swindler with true magical powers. The strength of the film is primarily how it explores the working class milieu of an Italian metropolis, where hidden and irrational desires are latent under the surface. Arcana is brimming with symbols and cues: just think about the oedipal (if not incestuous) relationship between the two main characters, mother and son, evoking the idea of a pre-modern matriarchal society. Some great moments are the boy’s quest for ingredients for a magic potion, or the séance in which Bosé vomits toads—which was, in fact, not a special effect! Another key feature of Arcana, is how director Giulio Questi contrasts the image of an anguished Milan with that of a magical and luminous Mezzogiorno with all its ancient ceremonies, peasant rites and so on: we see a donkey on top of a bell tower, an old man playing Taranta, submerged in mysterious atmospheres etc. Arcana is also a film with an experimental structure, and this is largely merit of screenwriter and editor Kim Arcalli. Together, Questi and Arcalli had previously created other important works such as Oro Hondo (the ultra-psychedelic Spaghetti Western of 1967) and Death Laid an Egg of 1968 (a “proper” Giallo). Arcalli is also the occult director of one of the most lysergic films of Italian cinema: Red Hot Shot by Piero Zuffi (1970), a sort of hard-boiled Noir with a serial killer portrayed by experimental theatre actor Carmelo Bene, accompanied by one of the greatest scores by Piero Piccioni.

Giulio Questi, Arcana, 1972

Are there any other titles that resemble Arcana in this hypothetical “fantasy-ethno-anthropological” sub-genre?

First of all, I would mention the extraordinary Il Demonio by Brunello Rondi (1963): at the time it was released, the film was reviled and misunderstood. It definitely is a controversial film, but its audiovisual power is immense, both in photography and sound (thanks to the electronic soundtrack courtesy of, again, Piero Piccioni). It takes place in a very different Italy than the usual one, and director Rondi adopts a quasi-documentary style to depict religious rites which contaminate Catholicism with superstitions and pagan beliefs. At the time, film critic Edoardo Bruno described it as one of the first examples of Italian surrealism, comparing it to Buñuel.

What’s the film about?

Il Demonio tells the story of a girl in a village in the South who is thought to be possessed, due to her all-consuming passion for a man. Rondi actually collaborated with Ernesto De Martino to give his film a credible anthropological layer, and managed to mediate among the most disparate influences, from Giovanni Verga (the godfather of Verismo) to Brecht. The protagonist, Purificata (literally Purified) is a sexually extrovert woman, and therefore inherently diabolical according to the village common sense. She is destined to remain a victim of society: on the one hand, Purificata is comparable with other designated victims of Italian cinema, whose transgressions are punished violently; on the other, she anticipates the topics of works such as Mario Bava’s Kill, Baby, Kill (which, despite being a Gothic film set in Northern Europe, includes a witch modelled on those of Southern Italy) and Do not Torture at Duckling (1972) by Lucio Fulci…

… which is the other classic “Italian Southern Gothic” film.

Absolutely. Fulci’s direction has these hyperrealistic, hallucinating tones which create a sense of eerie disorientation: just think of how the zoom is used to explore the arid landscapes of Basilicata, the highway that cuts the horizon like an open wound, and summarizes the clash between ancient and modern the best it can. Still, I would like to mention another title, The Night of the Devils by Giorgio Ferroni (1972), although more of a horror movie and set in the North, precisely at the Slovenian border. Here, a business traveler comes across a family of farmers who will turn out to be living dead: the idea is that they already are ghosts of a world that no longer exists, or if you prefer the remains of a peasant civilization wiped out by turmoil. We can also consider the so-called “Padan Gothic” by Pupi Avati a branch of this genre: in particular Balsamus (1968) and The House with Laughing Windows (1976) match the observation of the provincial realm with a strong grotesque and macabre touch.

Federico Fellini, The Nights of Cabiria, 1957

You mentioned the influence of Ernesto De Martino on films such as Arcana and Il Demonio. Regarding ethno-anthropological cinema, what about those documentaries made in the late 1950s and early 1960s directly inspired by De Martino’s work? Think about directors like Luigi Di Gianni, Gianfranco Mingozzi, Vittorio De Seta, Cecilia Mangini … Here too, what’s the legacy of this kind of cinema, beyond the simple “reality-as-it-is” representation?

Adherence to reality produces unusual effects, precisely because of the type of reality that is represented (often without commentary). Take, for example, Cecilia Mangini’s Divino Amore (1963): on the one hand, it connects to one of the most famous episodes of Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria—the pilgrimage to the sanctuary of Divino Amore in Rome; on the other, you have this clash between the pilgrims images in prayer, but also passionately eating spaghetti, and the dissonant, ultra avant-garde music scored by Egisto Macchi. The result is a weird, surreal documentary, showing the same occult adoration narrated in movies like Il Demonio: Christian icons worshipped as Pagan idols.