Italian Southern Gothic #2: Sicily 666

A visit to the place where Aleister Crowley founded his Abbey of Thelema

Italian Southern Gothic is a series of articles on how a hypothetical black Mediterranean imagery survives, hiding under the blanket of Latin clichés and vacation stereotypes, and how this is deeply embedded in the Mezzogiorno unconscious.

Halfway along the coastline from Palermo to Messina, suddenly one can spot a snail-like headland stemming from the horizon. A promontory made of marble and tuff stones. Here it is, Cefalù, my hometown. The snail shell is a meta-shell, a shell per square, a calcareous concretion actually filled with snail fossil shells (lumachella). Standing on the sea and overlooking the small town, the shell is wisely called ‘the Rock’ (‘a Ruocca). The two Cathedral towers are the snail antennas. According to the legend, the church was built by the Norman king Roger II to take a devotional vow; as his ship was wrecking in a tempest, he prayed the Lord and landed safe and sound, thus decided to build a fortress to acknowledge his saviour. Albeit never completed, it stands masterful at the feet of the shell since Roger’s death. Further implementations were added to the original structure throughout the centuries, amongst others a churchyard. Legendarily, this yard was made with the soil personally carried by King Roger from Akeldama, the Jerusalem blood-soaked field where Judas hung himself after having betrayed Jesus Christ. Allegedly, that ground would consume the flesh of the corpses in just few hours.

Since ancient times, Cefalù has been a poetic landscape where cruelty and beauty collided, embodying diverse transfigurations of the many battles men fought and lost against nature. In the folk imaginary, the Rock is not just a snail, but also the petrified body of the unfortunate shepherd Daphnis, punished by the gods for his envy; as a matter of fact, the word Cefalù comes from the ancient Greek Kefalé, meaning head. Facing De Chirichian bastion at the Marchiafava Cape, slightly touched by the lighthouse’s ray, a Drunken Reef (Scuogghiu ‘Mbriacu) emerges at low tide; it is so-called since a wine trading vessel crashed onto it at night. Apparently, Giants used to live in Cefalù, as the few cyclopean remains testify – although the skeletons were nothing but the remains of small pre-historical elephants. Fishermen can cease waterspouts and slay them with a knife, in some masterly gestures, reciting ritual verses. The Madonie, the mountains right behind Cefalù have their own personal chupacabra; it is called, onomatopoeically, sugghiu, and can literally devour a goat ‘from the legs up to the iliac bones.’ Names tell stories and things have tricky names. The Medieval Wash House by the Cefalino river mouth – sung by Boccaccio, is actually antecedent to the Middle Ages. Even Diana’s Temple could not possibly be devoted to the goddess of wilderness and hunt, as it is in fact a pre-Roman construction. At least one amongst these legends is true and properly documented, and tells the parable of men’s frailty. It is enough to face the theatre where this plot was set to understand how and why.

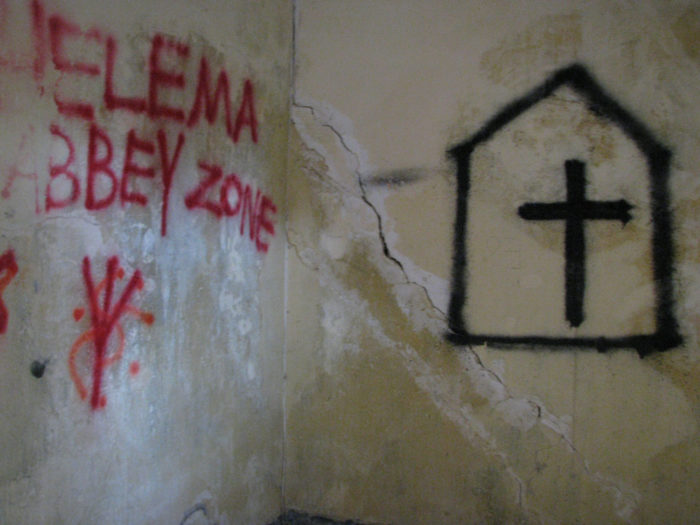

Walking through the undergrowth beside the local football stadium (now named after a friend of mine who committed suicide), one may spot something similar to a hovel amidst trees and bushes. When I was a secondary school kid, all my badass classmates used to go there at dusk to smoke cigarettes and commit vandalic acts, like torture some cats to prove they were cool or something. Although I was never there back then, I personally found their activities pointless and disgusting and did hate that place deeply. In my mind that was a dirty, deadly, somehow sick place, covered in dust and debris. When I eventually managed to get there myself for the first and only time in March 2016, my fantasies were duly confirmed. It looked as some sort of cheap horror scenery, something in between The Blair Witch Project and a Real Time show on compulsive hoarding, where those white trash are busy fixing their broken dwell. The place is fascinating, despite wrecked-looking it clearly has stories to tell. Decades before, my dad Nico had the very same feeling: the site was right next to his grandfather’s house and he used to play with his cousins just across. Back in the late Fifties (my dad was born in 1948), the building used to be called “the Mormons’ house” and was already semi-abandoned; people would make the sign of the cross when passing by. One day, my dad accepted his cousin’s recurring adventure challenge: get in there and explore. He entered the edifice holding a plastic axe in his hands to ward himself off. Advancing slowly in the dark, scared to death, all shakes and cold sweat, he spotted a fresco on the ceiling of a girl and a satire having a sexual intercourse. Suddenly, a scream. My dad dropped the axe and run away, shouting back. Despite the scream was just his cousin stamping onto a cat’s tail, my dad never went back to collect his axe. He returned only after decades, in the Eighties, to properly document the actual state of the house through the lens of the local history researcher, cabaret actor and folk singer he had become.

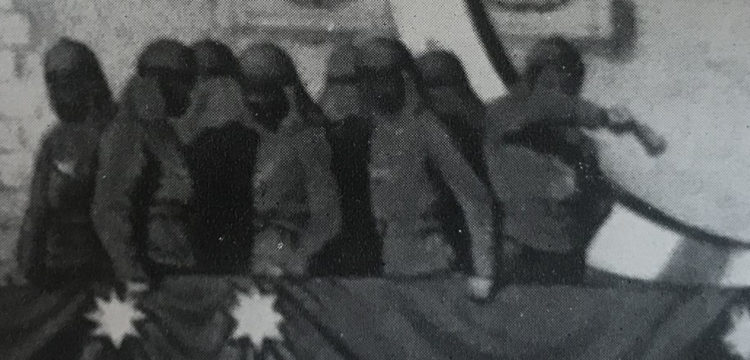

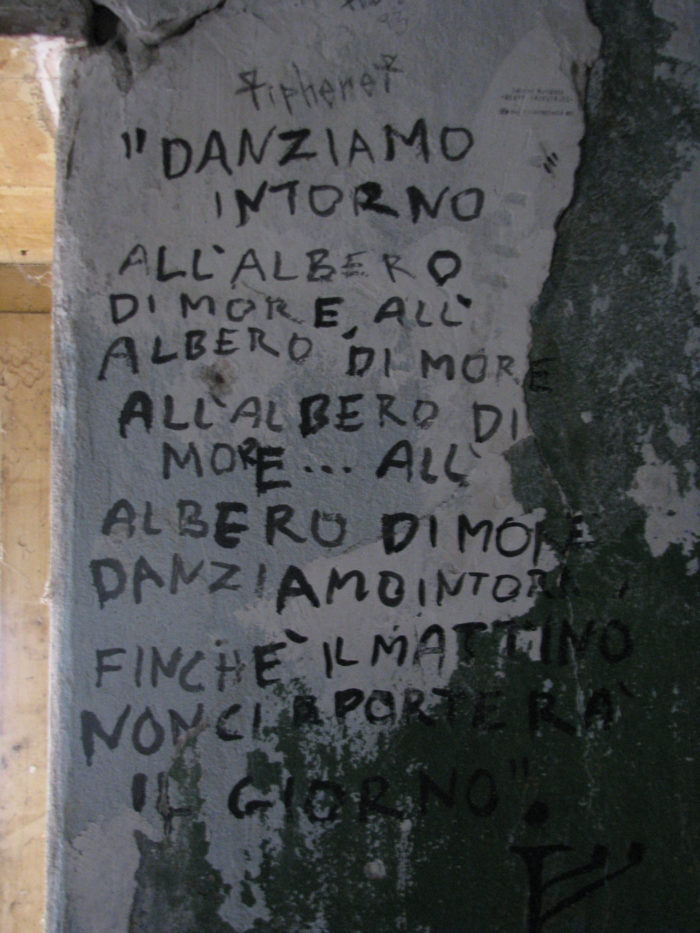

In any other geography of the civilized world, that place might have been protected, regulated, controlled, valorized for its historical and artistic value. For a bunch of years, that haunted house in the perfect Sicilian small town was indeed the most esoteric place in the Mediterranean: as mansion, church, and social laboratory of the greatest esotericist of the Nineteenth Century, the “wickedest man in the world” (an epithet coined by the London-based John Bull magazine in 1923): Aleister Crowley. Born in a wealthy family in Leamington, Warwickshire, in 1875, and educated in Cambridge, Crowley was a controversial poet, thinker, libertine and occultist who wandered across the world seeking for inspiration, knowledge, pleasure and fortune, and founded his own religion in the wake of the German wing of O.T.O. (Ordo Templis Orientis). Pushed by contingencies, after asking permission to the I Ching in Naples, Crowley moved to Cefalù on March 31st, 1920. With a few selected courtiers, lovers and proselytes he rented a factory owned by baron Carlo La Calce, right out of town in Giardinello (Little Garden; now Santa Barbara) beautiful countryside. There he established the “abbey” of Thelema, named after the one depicted in Rabelais’ Gargantua and Pantagruel, following the same one-rule: “Do What Thou Wilt”. He did put it in practice. The abbey was an ante litteram commune where Crowley experimented with writing, sex, magic, occult persuasion and drugs (as renowned heroin and cocaine addict). He covered the walls in grotesque – Goyaesque paintings and inscriptions, and organized recurrent rituals (which according to local rumours involved animal sacrifices).

The mysterious and creepy crowd who animated the house – growing in number through the years, due to rising interest and praise – soon became the main subject of a local press campaign; albeit discreet and elegantly dressed in black, blonde or ginger headed, the “Mormons” allegedly practiced polygamy. From the outside this feature was strictly associated to the cult, whose members were depicted as a group of whimsically styled and strangely behaving freaks. For some time, Crowley & Co. did manage to live peacefully aside the local community, in a way that Thelema was de facto accepted as an independent reality on the edge of town; somewhere not to snoop into, until it exceeded the local decency standard. The situation escalated quickly. Crowley stopped paying for the house supplies. Some children were born and never legally registered. Meanwhile several abortions and deaths – due to natural causes, such as infections or diseases, alarmed the authorities and shook the local community. The last casualty was Raoul Loveday, who drunk from a river and got enteric fever during a hike (Crowley was notoriously a proficient alpinist). From then on, the Thelemites started a diaspora. On April 23rd, 1923 the Mussolini Government officially banned Crowley for good. Broke and completely alone, he had to leave Italy and his most faithful lover of the time Ninette Faux behind. In order to repay debts, auctions were aired and objects sold. Some local dealers received pieces of furniture instead of money in exchange for the unpaid commodities. My great grandfather Giovanni, who was confectioner was amongst them. Unfortunately I am not an expert in the field and can not tell for sure, since facts here inescapably dissolve between gossip and legend. Anyway, it seems that some relatives of mine in my dad’s family happen to own at least a desk (with secret drawers) and a candelabrum coming from the abbey, reportedly employed in some of the Crowleyan rites.

I have never been particularly interested in Crowley’s mythology myself but for one key fact: it involved my hometown, and my hometown definitely did everything not to make the most out of it. Somehow, my family was involved as well, and that is why I wanted to know a bit more about the whole thing. I wanted to see with my own eyes. So I went to Thelema as a grown-up, accompanied by a well informed local guide who immediately made clear that most urban legends about this place were actually true. It is known that the peculiar figure of the Magus attracted much attention in the avant-garde world, within the social research field, and in popular culture. One and for all (that was the very first time I saw the face of the guy): Crowley is the top left egg-shaped head on the cover of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. In 1955, Crowley’s frescoes – covered in plaster immediately after his stay, were brought back to light and studied by the notorious sexologist Alfred Kinsey, accompanied by a well informed non-local guide: the film director Kenneth Anger (and the poet Fosco Maraini). Anger was so fascinated and influenced by Crowley to spread his vision all over the American avant-garde community. His cult movie Lucifer Rising (1972), featuring Marianne Faithful, Jimmy Page, and Mick Jagger’s brother Chris, was intended as a spiritual biopic of the magician. Page is a recurring figure in the saga as well. A huge fan and perhaps one of the most passionate collectors of his memorabilia, Page took a beautifully hand-painted wooden window from Thelema, and in 1970 bought the infamous Boleskine House, situated on the South-Eastern side of the Lochness lake, where Crowley used to live in the Nineteen-Tens. Another visitor of Thelema was Tool’s drummer Danny Carey, also a collector of Crowley’s memorabilia as well as expert in his doctrine (his personal website displays a condensate of such imagery).

Since his albums IAO (2002) and Magick (2004) are explicitly influenced by and dedicated to Crowley, I asked John Zorn if he ever visited Thelema, or better to say if he ever visited my hometown. And of course he did! I also asked him whether he would have been interested in the pieces of furniture owned by my relatives, who are definitely not Crowley’s enthusiasts and repeatedly tried to get rid of them. Indeed he was interested, meaning that he was curious about the whole story and got me sending him pictures and details: my grandfather, my dad, Anger, and Page etc. Like a good enthusiastic nerd he is in almost everything he is into, I guessed he already knew most of the story. I told him about the abandonment the house was exponentially falling into, and he was sincerely saddened by it. He still remembered the place being a mess, the collapsing roof (in that state already in the Nineties), and most of the frescoes being scratched away. Unfortunately, John was not into buying anything. Nevertheless he told me he could have put me in contact with some friends of his at the American O.T.O. Eventually, Butch Morris died, then Lou Reed, so I decided to drop the subject.

As private property belonging to baron La Calce’s heirs, Thelema has been repeatedly the object of a series of controversial and unclear real estate operations. Some rumours suggest that the house has been protected by some public institutions as if it was some sort of monument. Others that it was actually put into auction. Eventually it became the derelict building that it is now, abandoned to the public ludibrium and any kind of untraceable vandalism. Officially under the authorities’ seal, the house cannot be willingly demolished nor damaged by its owners, but at the same time the access has never been restricted nor the structure restored. Anywhere else, Thelema would have probably been turned into a museum that people visit and pay for. Surely its wild savage message would have been betrayed and dismantled, yet its value as a witness of an epoch and cultural artifact would be preserved and historicized. To me and most of my peers, it is and it could not have been nothing more than a slum where some brats used to go, kill cats and smoke cigarettes.

My dad’s adventure as young boy entering Crowley’s abbey is narrated by him in the book, edited by Pierluigi Zoccatelli, Aleister Crowley: un mago a Cefalù, Edizioni Mediterranee, 1998, p. 35. The pictures of the ruined abbey were shot on March 13, 2016.