Istituto Sicilia

Excerpts from the pilot issue of SICILIA: a journal on the Theory of Landscape, Art and Southern Epistemologies

The following texts are the editorial from Renato Leotta The Nature, The Museum and an excerpt from Pietro Scammacca’s essay The post-seismic museum, published in the first issue of SICILIA. In these texts the authors offer an account of the one the first museums to be opened to the public in Sicily, and speculate about the museum’s seismic genesis and the consequent orders display that emerged from the tectonic shifts of the Sicilian soil. These reflections resonate with the research that Istituto Sicilia aims to instigate on the theory of landscape and the connected epistemologies of knowledge, thoughts that have been first brought together in the pilot issue of SICILIA with a focus on the relationship between nature and the museum.

The Nature, The Museum

The experience of research and discussion that the publication of SICILIA journal aims to instigate stems from the desire to collect and share reflections on Sicilian matters, imagining the island as a fluctuating entity that ideally traverses the space and time of the Mediterranean. A circumscribed geography, but one that is under constant redefinition by human and non-human, mythological and real components. An island that, beyond the drifts of the summer season, celebrates complex cultural ecologies that construct and deconstruct the relations between nature and identity, the global and the indigenous. Sicily has always done so, often remaining, perhaps as a strategy of colonial resiliency, at the verge of the debate.

We have imagined the island in this way, a continuous set of layered natures and cultures where voices and images, writings, and desires, generate a museum. Nature and art are thus one great possibility of encounter and of fantasy alike. The first volume of Sicilia was born from this intuition, developed over a year and a half of exchange and research, that led to an exhibition project (1),which ultimately became a germinal process for this editorial series.

The study of the museum and its relationship with nature converge on the specific case of the Biscari Museum in Catania. This eighteenth-century initiative is considered to be the first public museum in Sicily as well as an important stepping stone in the understanding of collecting practices in Europe. In this first volume, that we will define as experimental, are gathered the reflections and materials produced as the result of a path disseminated with observations, pictures, and findings that overlap the features of the ancient to those of the contemporary.

Our considerations on the lost museum conceal a demand fed by the yearning of a new euphoria that may shorten the gap between 1758, the year in which the Biscarianum Museum was inaugurated, and us. It is therefore mandatory to present this new editorial adventure as a counterpoison, responding to the longing of visualizing a case—with the characteristics of the contemporaneity—that breaks through the temporal walls of the event and leans towards a continuous project.

The museum of Catania we will talk about was born a few decades after the devastating earthquake of 1693, with the aim of giving back to the inhabitants a sense of identity and collective memory founded on in the antiquities. Here, the meaning of heritage meets that of the museum by means of the act of rediscovery combined with safeguard. Prince Biscari’s collection goes hand in hand with the research campaign that will later lead to the discovery of the ruins which nowadays represent the archeological heart of Catania and other locations in Eastern Sicily such as Tindari, Camarina, Centuripe, Lentini, and many others.

It is not by coincidence that the birth of the concept of heritage in the nature-culture connection, as we know it today after the Italian Constitution, precisely originates in this context. It is what Benedetto Croce asserts observing in the decree of the right of the landscape that: (2) “nothing new, therefore, has been excogitated in the present regulation.” In fact, in 1744, still on the Etnean slope, by order of the Court of Royal Patrimony, a tree and some ruins were inserted inside a sole landscape protection act. Here the prototype of the museum of natures blossoms. This act concerned the Carpineto wood with its monumental chestnut tree of the Hundred Horses and the ruins of the Greek Theatre of Taormina. (3) Issued by a Tuscan Viceroy, Bartolomeo Corsini, this legislation is at least two hundred years ahead of today’s laws for the defense of landscape and natural beauties. Laws which should be studied today, and especially in Sicily.

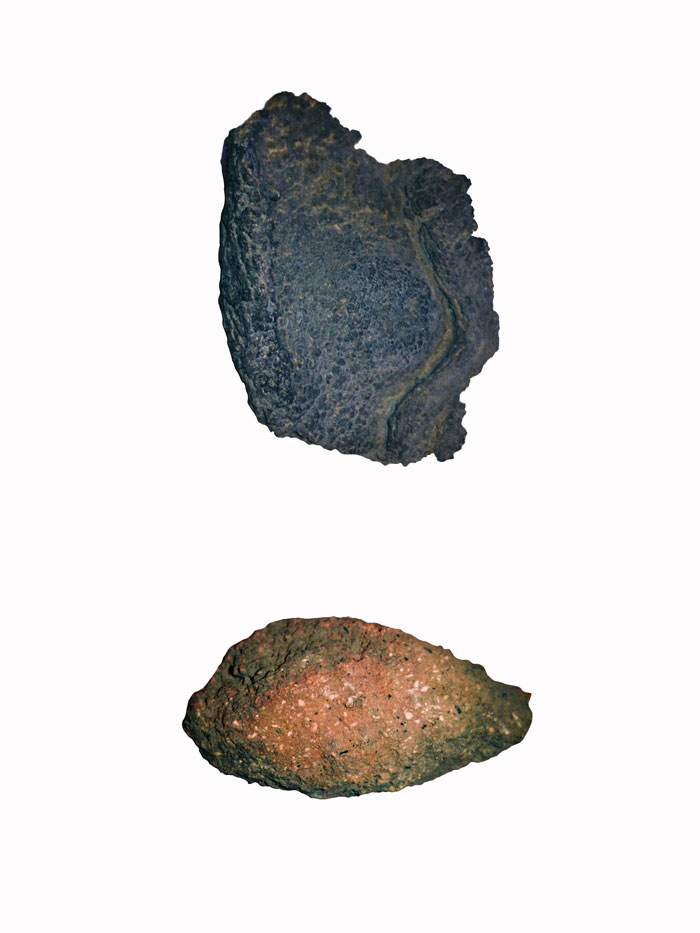

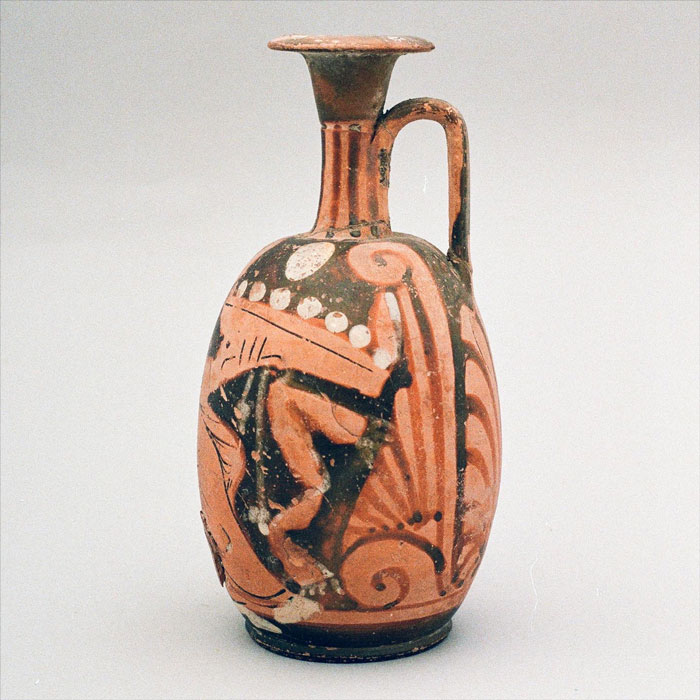

Just as a tree and a ruin come together on the slopes of Etna, the same assortment is presented within the collection. Naturalia and antiquities are two distinct classifications of collecting praxis of the time, yet the cataloguing of things in the Catanese Museum is more equivocal and less gridded than the order configured by European colleagues. The handling of objects was often paced by a rationale that we might describe as “by feeling” or by “order of beauty.” This method, not necessarily less correct than others, stemmed from a vision that posited objects as products of a time when the hand of men was still guided by the sky, subordinated by archaic rules. (4) The world drawn by these ancient artists, found by the Prince among the earthly folds of the earthquake, was necessarily connected to nature by way of myths.

The recovery of a leaflet of notes in the Museum Bischerianum, a manuscript considered until now to be lost, (5) partly supports the argument of a cosmogonic museum. The document in fact lists a series of deities followed or preceded by small signs and crosses made by Biscari’s hand. Here in Sicilia we include some of the female divinities present in the folder we have retrieved and leave a more extensive publication of these materials to a future in-depth study.

The sense of this series is also based on the trust in the analogical condition, the work of observation and study carried out on the objects and productions of nature have provoked in us, as a natural response, the desire to publish. This act, as one might say, of putting pen on paper echoes the fall of ash carried by the wind onto our pages by the recent volcano’s activities. The fall of this unreleased and infinitesimal material, produced by a puff, tells us about the micro-macro scale relationship that our topics want to tackle and underlines possible strategies of cooperation with nature.

_____________

(1) Renato Leotta, Mondo, Museo Archeologico del Reale, curated by Claudio Gulli and Pietro Scammacca, 11 July – 30 August 2021, Palazzo Biscari, Catania.

(2) Law June 11, 1922, no. 778 – Art. 1: Sono dichiarate soggette a speciale protezione le cose immobili la cui conservazione presenta un notevole interesse pubblico a causa della loro bellezza naturale o della loro particolare relazione con la storia civile e letteraria. Sono protette altresì dalla presente legge le bellezze panoramiche.

(3) It concerns two plurimillenariums trees in the territory of the municipality of Sant’Alfio, Catania. “Per la conservazione de’ meravigliosi alberi nel bosco del Carpinetto sopra la città di Mascali”…“affinché si conservino gli antichi Edifizii della città di Taormina”. Sulle origini e le funzioni del Tribunale del Real Patrimonio. M. Costa – P. Torrecchia.

(4) On the “archaic thinking” the myth is understood as an exact science. Cfr. Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Dechend, Il mulino di Amleto, Saggio sul mito e sulla struttura del tempo, Milano: Adelphi, 2003.

(5) Stefania Pafumi, Museum Biscarianum. Materiali per lo studio delle collezioni di Ignazio Paternò Castello di Biscari (1719-1786), Catania: Alma Editore, 2006.

The Post-Seismic Museum

After visiting the Museo Biscari in 1781 the French geologist Déodat de Dolomieu remained unimpressed by the museum’s collection of natural history which he described as “without order, without method,” as an amassed exposition of elements in which “the productions of Sicily are scattered amongst those of other countries, very few of which are worthy of attention.” A few years later Vivant Denon, the first director of the Louvre, would visit the Museo Biscari and the Museo dei Benedettini only to conclude that the collecting practices in Catania were comparable to the “impulse of an ant, who collects and accumulates without choosing.” The lamentations from the acclaimed geologist and the father of modern Egyptology point to the Museo Biscari’s incompatibility with French grand goût, the evolving taxonomic principles of the time, and Northern European museological canons generally speaking.

Archive of Istituto Sicilia.

A rigorous project of classification was even abandoned by Domenico Sestini, the Florentine academic engaged by Ignazio Paternò Castello, V prince of Biscari at the end of the eighteenth century to catalog the collection. Sestini’s methodic room-by-room description of the museum seems to fall apart when he reaches the gallery filled with figurative terracotta statues: “But oh here,” he exclaims with astonishment, “that I see myself somewhat embarrassed to be able by the great haphazard quantity and diversity of things to describe them, as well as to classify them subject matter by subject matter!” Other sections of the museum, such as the collection of the bronze instrumentum domesticum, presented “a rather chaotic and heterogeneous collection,” as indicated by the archaeologist Stefania Pafumi in her recent study of Biscari’s collecting practices, who, she writes, “never attempted a rigorous and typological classification aimed at the construction of chronologies.” He was rather interested in an “internal” analysis of the objects he found undertaken by “entering into the examination of their invention,” as described by the prince himself.

This “chaotic and heterogenous” character of the collection is also explained by the fact that the Museo Biscari was an example of what I would call a “post-seismic museum,” given that it was conceived and instituted after a devastating volcanic eruption and earthquake that destroyed much of the city and the Eastern part of the island. Comparable to Catania’s Museo dei Benedettini, which was inaugurated a few years before, Biscari’s project was initiated with the intention of “returning” to the inhabitants of Catania a sense of identity and collective memory founded in the antiquities that surfaced through the fissures in the island’s broken ground. With the exception of some acquisitions made in Rome, Naples, and Florence, the collection of the Museo Biscari was largely composed of objects that had been excavated underneath the layers of dried lava from the eruption of the Mongibello crater in 1669 or recuperated from what remained of the ancient ruins that survived the tragic earthquake of the Val di Noto that took place a few years later in 1693. As Sestini mentions at the beginning of his introduction to the Museo Biscari:

Such monuments were found at different times, and especially on the occasions in which the aforementioned Prince, in order to preserve what belongs to the venerable antiquity, generously undertook to make several excavations in the conspicuous City of Catania. Of greater consequence were the discovery of the Theatre and the Amphitheatre, where it was already conjectured that many memories had been buried by the eruptions of the Mongibello and by the earthquakes. The excavations brought back these memories with a singular glory, as well as other things of great importance.

These opening lines by Sestini leave one to imagine that much of the content of the Biscari collection was not strictly selected according to historical doctrines, but was rather symptomatic of the seismic reshuffling of the palimpsest that is the Sicilian layered ground. The museum leaks through the open cracks of the landscape.

That there was an attempt by Biscari to, nonetheless, give some order to his collection of antiquities is most evident in the unpublished catalogue of his collection, Museum Bischerianum (1776), which Renato Leotta, Claudio Gulli, and I stumbled upon while searching the archives of Palazzo Biscari. The manuscript, hand-written by Sestini under strict guidance by Biscari, remained incomplete and was thought to be lost or destroyed and contains 101 reproductions drawn in pencil and grey watercolors of the statues representing heroes and Greco-Roman gods that were part of the prince’s collection. The plates are divided and numbered according to the represented divinities and not according to a hypothesised chronological order or any sort of geographical index. This unpublished manuscript demonstrates that Biscari attempted to organize his museum according to a mythological order, as if his archeological endeavors were aimed at reconstructing a divine cosmology buried underneath the decomposed Sicilian soil. In this way, he organized a collection that was in tension between a seismic genesis and a search for an idealised celestial order.

Archive of Istituto Sicilia.

After the death of Biscari in 1786, the museum entered a gradual state of disrepair. At the beginning of the nineteenth century it was already “well below its great reputation for the disorder in which its collections were exposed,” due to the fact that Biscari’s nephew, Ignatius VII, had moved his permanent residence to Naples. In the 1930s, almost two hundred years after the inauguration of the Museo, Guido Libertini, the archaeologist in charge of documenting and archiving the passage of the Biscari collection to the Civic Museum of Catania, found a museum that was completely left to entropy. He writes: “It is hard to imagine the state of abandonment to which the museum was subjected to: the two internal courtyards were reduced to a scrubland. In the semilit corridors, the objects were covered with dust and mold, the showcases were moth-eaten and crumbling. Some of the shelves had detached themselves from the walls due to the humidity, dragging in their fall the vases that they supported and those below.”

Here, for a moment, the Museo Biscari slips out of focus and resists the archaeological gaze. The archon disintegrates, like Gradiva’s footsteps vanishing in volcanic dust. Artifacts become matter again, the museological taxonomy and its supporting structures have surrendered to the grain of the universe. The time trapped in the museum has been set free.