Intellectual Work and Augmented Intelligence

Intellectual work and capitalist development in relation to augmented forms of intelligence and their implications

For his exhibition We walked toward the music and away from the party at Fanta, artist Noah Barker commissioned architect and writer Alessandro Bava to translate from Italian to English a 1969 text by architecture historian and theorist Manfredo Tafuri titled Intellectual work and capitalist development. The exhibition is a “publishing pavilion” for the text which is printed in a series of white books containing different edits and versions of the translation. Tafuri wrote this text for the marxist journal Contropiano as a long and dense study on the role of intellectual (and creative) work within capitalism. The translation was intended as a constitutive element of the project, as a performance of the very intellectual labour Tafuri analyzes in the essay. The text that follows in an attempt to further continue this performance and read Tafuri’s text and his position on automation, in relation to augmented forms of intelligence and their implications.

Understanding the consequences of the automation of certain logic and rational processes of the human collective intelligence and their externalization into digital machines has become the unofficial task of the contemporary intellectual worker. If 19th century automation of mechanical processes based on thermo-dynamics and its consequences on humans, was the motive behind Karl Marx’s analysis of capitalism, today the increasingly pervasive automation of cognitive faculties has the immediate effect of devaluing ever larger sectors of what used to be known as white collar labor, and therefore a potentially radical shift in the social division of labor.

In his 1969 essay titled Intellectual Work and Capitalist Development, a leading Italian architecture historian and theorist Manfredo Tafuri tracks the evolution of intellectual labour and its progressive commodification, a process by which thinking becomes labour. Tafuri’s attempt is to understand the role of culture as a reactionary, reformist, utopian or revolutionary practice. Within this scope, Tafuri includes remarkable pages on the development of technologies which automate intellectual labour, thus providing materials for a critical theory of automation, and more specifically automation in architecture. While in the text the direct references to architectural knowledge are limited to urbanism, it could be said that the implications of his study of intellectual labour are ultimately directed to recasting the role of the architect within capitalist development.

Installation view Noah Barker, We walked toward the music and away from the party, Fanta-MLN, Milan, I. Courtesy the artist and Fanta-MLN, Milan. Photo Roberto Marossi

Architecture as a conceptual and technical discipline and building as a material practice are a very good case study on the changes brought about by automation and how they impact both the intellectual work of the architect and the manual work of the builder. Moreover speaking about architecture always implies speaking about life, as architecture is a device that reifies and produces the mechanisms defining collective life-forms. Thus when speaking about automation in architecture, one cannot escape understanding how this specific set of techniques affect life processes tout-court.

For the purpose of contextualizing Tafuri’s research I must make a brief and necessarily simplified detour on the current political circumstances of the employment of augmented intelligence and the paradigmes of automation it enables. Today the transformative potential of augmented intelligence pivots around the fact that most of its building blocks are subject to patents and are thus proprietary technologies belonging to a small handful of private American corporations and Chinese state institutions, giving rise to a new form of cold war. Even American academic institutions, for example, a buffer between production of knowledge and their potential applications, are suffering from an hemorragie of researchers attracted by more lucrative and actually more scientifically advanced opportunities within corporations: a situation comparable with the invention of printing as a de-facto open-source technology.

Rather than intrinsic aspects of the technologies, this fact is the main concern of a critical discourse on technology: “Who counts? Who computes? Algorithms and machines do not compute for themselves; they always compute for someone else, for institutions and markets, for industries and armies.”

As the developments of automation and augmented intelligence find more application outside the already established uses in finance, manufacturing, and management within the opaque NDAs of private companies, technologies supposed to preside and govern over this new productive and existential paradigm, such as political science and generally political technologies, struggle to catch up, despite the efforts of many political theorists whose work remains firmly outside mainstream discussions.

Large parts of the economy are already fully or partially automated (think of bot-to-bot speculative transactions and the very functioning of contemporary monetary systems) and are thus increasingly detached from “real” material economic processes, the ever increasing polarization of wealth (in terms of class and geography) is producing, at least from what I can see, a huge demand for new political paradigms to govern such dramatic technological evolutions.

Noah Barker, Untitled (Neutral Oasis), 2019. Courtesy the artist and Fanta-MLN, Milan. Photo Roberto Marossi

Noah Barker, Neutral Oasis, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Fanta-MLN, Milan. Photo Roberto Marossi

What the Economist has called “millennial socialism” could indeed be interpreted as a struggle against automated and neoliberal economic forms, and the rampant inequality they seem to produce. The unprecedented rise of democratic socialism in the US, which currently drives political discussions and the work of new transnational online-based party structures such as Diem25 in Europe, who interpret the demands for more equality, regulation of partially automated economic ecosystems such as finance and an ecological agenda such as the Green New Deal, reveal a generational struggle which begins to emerge.

The pages Tafuri dedicated to aspects of computer science and the role of the intellectual worker vis a vis hegemonic structures of power, have up until now been ignored, perhaps due to the obscure and still imprecise terminology used, however it is interesting to address them today, given the context I just laid out.

This is not just for the purpose of an “archaeological” study of Tafuri’s work but because I believe some of his observations are precious to the discussion and can contribute to the development of a critical framework, at the very least for architecture, which can allow us to imagine possible and impossible futures enabled and supported by emerging technological paradigms. Within a wide ranging analysis of intellectual labour, Tafuri presents a rather unique insight in the conversations happening in the 1960s on computer science, as a set of technologies aiming to automate certain aspects of natural languages and, most importantly, formal logic.

While Pier Vittorio Aureli has already discussed in depth the historical context of this essay and its core argument of questioning the practice of intellectuals within capitalist societies, here I will briefly discuss the specific pages providing elements for a critical framework on automation.

Installation view Noah Barker, We walked toward the music and away from the party, Fanta-MLN, Milan, I. Courtesy the artist and Fanta-MLN, Milan. Photo Roberto Marossi

Leibniz, one of the fathers of computational theory, explained the aim for his concept of calculus ratiocinator in such terms: “it doesn’t make sense that men waste time and rack their brains to make calculations if these can be done by a machine.” This very aspect of automation as an agent of freedom is what lies at the center of the marxist critique of technology. One of the founders of Italian Operaismo whose work as a theorist had a focus on the critique of technological innovation, Renato Panzieri criticizes this neutral freeing of time as being immediately subsumed by capitalist accumulation; in fact this question was also discussed by one of the most important Italian computer scientists and theorists, Alfonso Caracciolo, often quoted by Tafuri, who explains this freeing of time as enabling more employment of specialized workers.

Tafuri writes in the aftermath of the first developments of computer science in Italy which can be traced back to the work of Enrico Fermi who in 1957 exhorted Adriano Olivetti to invest in electronic calculators, and the work of Ettore Majorana whose discoveries would initiate the study of quantum physics (and ultimately quantum computing) within a general effort already since 1954 to catch up with the developments of computation in the United States and their proven transformative power over industrial economic processes and scientific research at large.

Casting a wide net on the issue of cognitive labour, Tafuri encounters this new discourse on computation and automation, and includes it in a lineage starting with an analysis of the historical avant gardes and their role in the socialization and definition of new values of post-industrial societies. The main source on computer science analyzed in the text is Linguaggi nella società e nella tecnica a 1968 collection of the international contributions to a conference organized by Olivetti. Tafuri here explicitly connects the development of computation with the emergence of more accurate “decision making techniques” and trend forecasting, identifying these with the need for capitalist development to be able to forecast, predict the future to implement economic planning. With a rather brilliant intuition Tafuri connects these technical and scientific developments with the emerging philosophical currents of Structuralism and the work on language also pervading artistic research in the 1960s, criticizing its apparent retreat into pure formalism, as actually productive labour which run parallel to the development of computer languages.

Tafuri focuses on the emerging field of programming languages, as they are directly connected to the traditional labour of the intellectual worker on language, literature and other written forms: particularly the transformation of linguistic disciplines from analytic techniques to an aid for the creation of highly formalized programming languages, necessary to be able to compute any type of data. Caracciolo notes how the need of developing new powerful linguistic systems, generative languages (the ones enabling technologies such as deep learning), is at the core of the research on language. Tafuri connects this effort with Russian formalism and communist Russia enthusiasm for technological developments based on the study of language, and electronic music, in particular the work of architect and composer Iannis Xenakis in which “the relationship between ideology and programming science is inverted. The general theory of signs enters heavily in aesthetics and formal research: the absolute coincidence of the sign with itself, the disappearance of any external meaning, the objecthood of the artistic phenomenon, ceases to be a project and becomes pure objective fact, that can be evaluated with binary systems, not just a hypostasis of cybernetics, but also the last attempt to emancipate from it.”

This appraisal of early electronic music experiments is rather surprising and reveals the idea of using machine ‘intelligence’ as a mimetic copy of human cognitive processes for purely phonetic and visual experiences as a potentially interesting development of these technologies.

If we consider how the development of ‘techno’ music and its transformation in a quasi-working class religion or at least near-transcendental experience, and its class and racial roots in the impoverished working class of fordist Detroit, it could be said that Tafuri’s position already foresaw how these technologies could be appropriated and used, rather than for the purpose of managing class-struggle, towards class-liberation.

Installation view Noah Barker, We walked toward the music and away from the party, Fanta-MLN, Milan, I. Courtesy the artist and Fanta-MLN, Milan. Photo Roberto Marossi

At the same time Tafuri warns against an understanding of what he calls “electronic art” as the technicization of aesthetic processes which lead to an exasperated autonomy of those processes from reality, thus realizing the impossibility for intellectual work to produce any utopia, erasing any tendency towards a “project” and creating semantic voids. Very important is Tafuri’s reference to the work of Max Bense, a German philosopher concerned with the ethical and aesthetic dimension of natural sciences and technology. Following Ludwig Wittgenstein’s work on language, Bense developed an aesthetic theory of mathematics from the informational atoms of language which could be combined to generate metrics and rhythms separated from meaning, in an attempt to escape the analogy he recognized between Hegelian dialectics and cybernetics as both leading “to an idea of consciousness entirely referred to the Funktion,” the rational accomplishment of tasks.

Tafuri notes how the elevation of rationality to a value is the central problem even within a critique of ideology: he warns that as rationality is the main tool of development of what he defines as the “capitalist plan” to elevate it to a value does not escape the dilemma of questioning rationality as implicit in the processes sustaining the plan itself. Even if Tafuri doesn’t push this line of thinking further towards a “project,” I am tempted to speculate on whether the main project of any critical practice today is to understand how to escape the rational paradigm of capitalism, to imagine other paths of consciousness on which to establish a post-capitalist scenario. Any counter-project is thus obliged to coalesce a new paradigm of use for human consciousness, much like the one attempted by Federico Campagna in his recent book Technic and Magic.

In regards to architecture what emerges from a provisional critical framework for augmented intelligence and its consequences on the built environment is the necessity to abandon attempts to develop a specific “style” of design linked to the languages of computation and the aesthetics of mathematics and oriented towards the mantra of newness seen as an unquestioned and unquestionable telos of any material production, and rather reclaim architectural knowledge as the specific competence of inhabitation as a psycho-political and phenomenological art, in which the only newness one should aim for is to increase equality, wellbeing, and joy. Therefore what is needed, besides a comprehensive political framework and lebensform, is rather to (re)discover abandoned methodologies of design and ways of inhabiting and thinking about space.

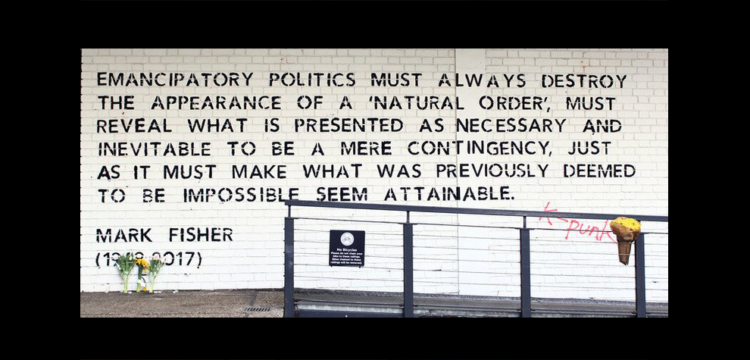

Perhaps it is truly time for what Armen Avanessian and Markus Miessen have defined as Xeno-Architecture to match other emerging xeno practices, speculative concepts that are crafted as fully formed alternative futures rather than produce additional critical readings of the present. These practices must counter the current millenarist obsession taking over cultural and political debates, ever more strongly reinforcing what Mark Fisher famously identified as the limit of capitalist realism: it is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.