Infinity Pool

Following the monstrous Tiber

Infinity Pool is an imaginative exploration whose purpose is to summon monsters. It is a strategy to put a face to what remains invisible because it flows away from the meshes of our practices.

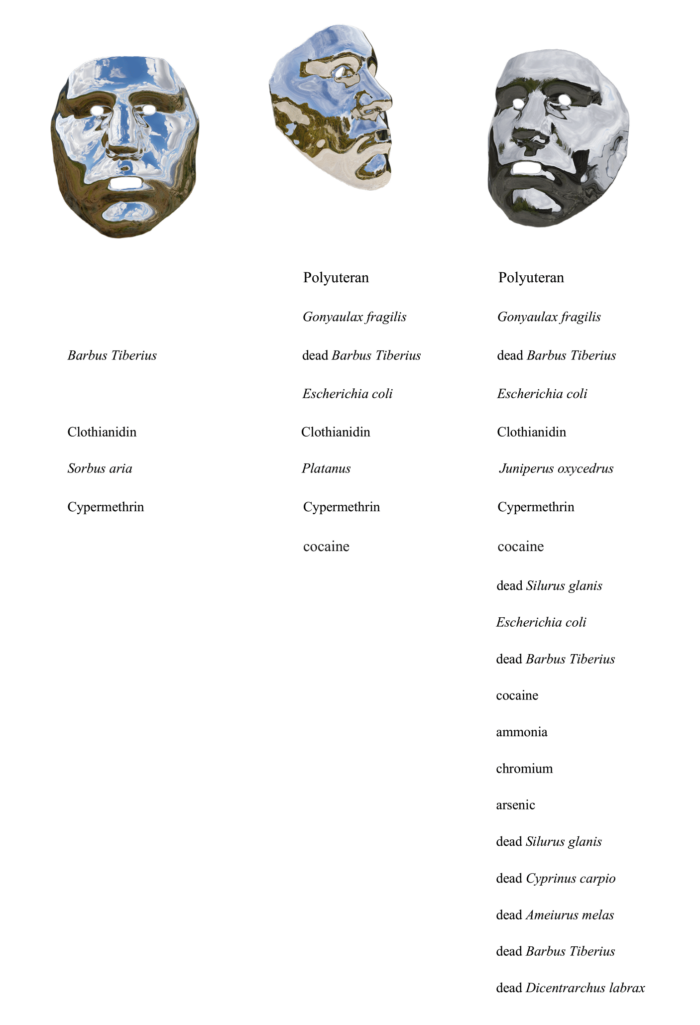

Infinity Pool, created in collaboration with landscape architect David Habets, and with visual support from photographer Valeria Scrilatti, revolves around the design of a mirror mask and is composed of three walk performances and a video installation.

It is part of a philosophical practice that moves within the framework of embodied philosophy of mind using unorthodox means.

In the course of time, we intend to develop these explorations along different rivers and through heterogeneous places that will feed into the long-term Future Monsters project that I founded with the purpose of collecting various monstrosities.

Living in a time of planetary catastrophe thus begins with a practice at once humble and difficult: noticing the worlds around us.—Swanson-Tsing-Bubandt-Gan, Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet: Ghosts and Monsters of the Anthropocene

Presidente: “Luigino di’ ‘non posso mangiare il riso con le dita così’”

Luigino: “Non posso mangiare il riso”

Presidente: “E allora mangia la merda!”

—P.P. Pasolini, Salò, or The 120 Days of Sodom

Intro – Here is born the river sacred to the destinies of Rome

[Qui nasce il fiume sacro ai destini di Roma]

Summon monsters to know their faces; walk through them in their gaseous conformations and inhale their volatile particles.

If what threatens us is invisible, how to give a face to that which shows up manifest only after the piles of bodies have accumulated? In addressing the climate crisis, in order to identify a culprit, we should look at our practices first and pay attention to the specific ways in which we bring forth them, organize materials, produce the abject, and discard the remnants.

With Infinity Pool we try to capture the invisible climate threat through an iridescent mirror face. The situated monster we try to evoke indicates a connection between fascism and the climate crisis, but for now, it is only a reflection that refers back to the image of a river at whose source is a monument with the imperial eagle and she-wolf in effigy, and ends its course with the corpse of a poet.

In a beech forest on Mount Fumaiolo is a stele indicating the source of the Tiber River. Until 1923 the territory around the mountain was part of Tuscany, but Benito Mussolini in order to link its origins to the “river sacred to the destinies of Rome” decreed a change in the boundaries between the provinces of Florence and Forlì by including in the latter—where he was born—the source of the Tiber, more precisely in the municipality of Verghereto.

On August 15, 1934, a public event was organized for the unveiling, where the Tiber springs, of a marble monument—a column from the Foro Romano—in which the eagle and the Capitoline she-wolf, symbols of imperial Rome, stand out.

On the monument is an inscription:

Here is born the river sacred to the destinies of Rome.

Riverbeds

The activities in which we are constantly engaged flow through a bed of practices that in turn constrain the activities within them, just as the riverbed with the movement of water. At the same time, the movement of the water modifies the riverbed itself. This is what Wittgenstein meant when he stated:

“…I distinguish between the movement of the waters on the river-bed and the shift of the bed itself; though there is not a sharp division of the one from the other.”

Activities bring forth established practices that develop over very broad time frames and determine a particular way in which things are done. Practices define how we organize and select materials. Selected materials constrain further activities that bring forth established practices. They are the set of practices that constitute our form of life and consequently, what is relevant to us. The psychologist James Gibson spoke in this regard of “education of attention”: our contact with the environment occurs through the practices in which we have been educated; each of these lets some environmental invitations emerge as solicitations whereas excludes all the others. Anthropologist Tim Ingold, to define this process of attentional selection, gives the example of a novice hunter who learns by being led into the woods by more experienced hands. The novice who finds himself/herself moving among the undifferentiated foliage is led to develop a sensitivity to the qualities of surface texture by which, simply by touch, he/she will be able to determine how long ago an animal left its footprint in the snow and even how fast it was traveling; in short, the young hunter is guided to notice aspects that he/she would not otherwise have picked up on, thus coming to develop a perceptual awareness of the properties of his/her surroundings and the possibilities for action they offer. But, as the philosopher Erik Rietveld points out, since we are selectively open to the rich landscape of affordances that characterizes our ecological niche, this implies that what is not selected by the practices in which our bodies have been forged remains unseen. There is much that is invisible to us.

Not us

The 2023 report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) returns an extremely clear and disturbing picture of the effects of anthropogenic action on the Earth and warns of possible future scenarios: if we do not completely rethink our habits so as to drastically decrease CO2 emissions, the global temperature will be destined to increase until, presumably by 2100, it will exceed pre-industrial temperatures by 3 degrees Celsius; sea levels will further rise, oceans will warm and become more acidic; atmospheric turbulence and thus possible weather events of catastrophic magnitude will intensify. Ecosystems, both terrestrial and marine, will not be able to adapt to the rapid rise in temperatures, and this will lead to changes in the geographic distribution of animal and plant species in addition to the loss of biodiversity.

The emission of CO2 is linked to a range of practices—burning of coal, oil, and gas, deforestation, intensive livestock farming, the use of nitrogen fertilizers—that we might bring under an “extractive” attitude toward the environment: there is something out there, a “not us”—materials, vegetations, human and nonhuman animals, that we can dispose of at will because it has been excluded from our community.

There is something out there that for centuries we have characterized as radically other from which to extract substances and profit. Relegated to the margins of our perception, what is out there, through elements from time to time more recalcitrant appears, shows itself as monstrous and, by showing up, shows us to ourselves for what we are. Something out there that we did not consider, discarded at the limits of our form of life, forgotten in the depths of our lives—like Frankenstein’s Creature, a good giant turned evil, it now reappears to take revenge.

Monsters—from seeing to seeing differently

The monster walks on the border of the visible. It expands what is there to be seen and that a community excludes or is unable to perceive or seize as an opportunity for action. As the father of “monster studies” Jeffery Cohen writes in the seminal Monster Theory, the monster is always escaping, crossing disciplines, and straining the tightness of conceptual meshes; it cannot be grasped, in fact “when its secrets are about to be revealed it rises from the dissecting table and disappears into the night.” The monster polices the limits of the possible but it can even open gaps and dynamize dichotomies; “harbinger of Category Crisis” it is a difference made flesh.

The term “monster” comes from the Latin monstrum, which is related to the verbs monstrare (“to show” or “reveal”) and monere (“to warn” or “forebode”). A monster is a kind of omen that indicates something disturbing or threatening that populates our world. In practice, this horrifying creature shows us something and, by showing what we were not able to see before, warns us; in this sense, it can be linked to a very specific form of “education of attention” in which an imaginary being is used to point out what by remaining at the periphery of our perception potentially constitutes a threat.

The monster can facilitate the shift from “not seeing to seeing” or from “seeing to seeing differently” that the philosopher Alva Noë talks about; seeing is not something that happens within us but something we do. Perceiving is much more like the ability to climb a tree rather than a digestive process.

In order to see differently we have to do something different, which does not mean just merely changing our point of view, as if simply moving through space with the body we have forged so far,—and with the repertoire of skills we have acquired that have pre-selected what is there to be seen—could let emerge aspects previously precluded to us. To see differently we need to bring forth new practices first and engage ourselves with a different education of attention.

We need a monster (monstrare) in order to prevent a catastrophe (monere)!

That to see differently requires transforming practices is taught to us by anthropologist Viveiros De Castro’s cannibal metaphysics: what an entity is depends on the network of relations in which it is embedded, that is, by what practices it is defined. A fish may be a waste dragged from the waters, but it could be food if cooked, a source of profit if farmed, or an unusable sample for the local health authority in Rome if the bodies taken had colliquated, that is, liquefied organs. As ethnographer Annamarie Mol argues, “variations [of the object] is not in the eye (ear, nose, tongue) of the beholder, but in what relations make of reality.”

Infinity pool

Infinity pool is an art project consisting of a performance and video installation conceived in collaboration with landscape architect and researcher David Habets and with visual support from photographer Valeria Scrilatti.

As a prototypical example for the creation of Infinity pool, we imagined developing the project in the city of Rome, and more specifically along the course of the Tiber River.

Infinity pool revolves around the design of a mask that will be made of glass and chromed to be reflective. It will be worn as part of three performance walks in which local residents will be involved. We have developed the hypothesis of staging Infinity pool in three different places: 1) on the top of Mount Fumaiolo where the Tiber has its source; 2) on the Lungotevere where the Tiber crosses Rome; and 3) on the beach in Ostia where the Tiber flows into the sea. During each walk, participants will be able to collect what they encounter along the way, including water samples, which they will hand over to the performer.

With a video camera placed over the mask and pointing at it, we imagined recording its reflections. In a second phase, these reflections—moving selfies of a landscape in flux—will be projected in a film/theater/museum space.

The projection will be accompanied by words spoken by the individual masks. These words will refer to the objects, the chemical components related to the water samples collected by the live performance participants, and the natural or human elements reflected on each mask. The materials in the specific locations will thus define the faces of the looped projected environments.

What usually appears distant or unimportant to our lives is now invited to come closer and stare at us closely.

We imagined a possible dialogue between the three faces—the Source of the Tiber, the face of the Tiber crossing Rome, and finally the Tiber flowing into the sea.

Outro – Destiny

Near the mouth of the Tiber, at the Idroscalo in Ostia, the body of Pier Paolo Pasolini was found on November 2, 1975.

…the river sacred to the destinies of Rome.

The etymology of the word “destiny” is related to the Indo-European root sta-, hence the Greek ἵστημι meaning “I stand.” From the same root comes the Latin de-stinare (prefix de + stinare, an elongated form of stand). This word is related to stele, staticity, and stability.

Destiny is linked to the idea of a predetermination of things happening in an unchangeable way, the result of a will that is above the capacity for human action and understanding. We usually use the word “destiny” with terms such as “undergo,” “resign,” “accept,” “follow.”

The Tiber River begins with a stele whose presence emphasizes the stability of the riverbed—emphasizing that illusory distinction, the seemingly rigid and unchanging bed of our practices. Letting our abilities flow without monstrous interruptions into that bed brings waste of all kinds toward the mouth.