In the Sky I Am One and Many

…and as a human I am everything and nothing: Anna Maria Maiolino in conversation with Ines Goldbach

Anna Maria Maiolino is an Italian-born Brazilian artist. Curated by Ines Golbach, her first institutional solo exhibition in Switzerland features a selection of her early videos, films, photographs, sculptures, drawings and texts, spanning a narrative arc through her artistic work and life from the 1970s to the present. The following conversation took place between mid-March and mid-May 2021.

Ines Goldbach: I’d like to start by talking about language, which plays a central role in your work: language as a source of identity, as a way of expressing yourself, and as a malleable material at the same time. You were born in Italy, emigrated to Brazil with your family when you were young, spent a few years in New York, and then returned to Brazil, where you still live today. Your exhibitions around the world have always brought you back to certain places. We speak Italian and English together. Your catalogues and books, as well as the titles of your works, are in Portuguese and English. What does this form of multilingualism mean to you? In which language are you most at home? Is there a language in which you can think, speak, dream, or even find titles particularly well? How do the languages differ for you?

Anna Maria Maiolino: Speech and language have always stoked my imagination, my fantasy, in a particular way, despite the dilemma and difficulty I have faced learning the languages of each new country in which I have lived as a foreigner.

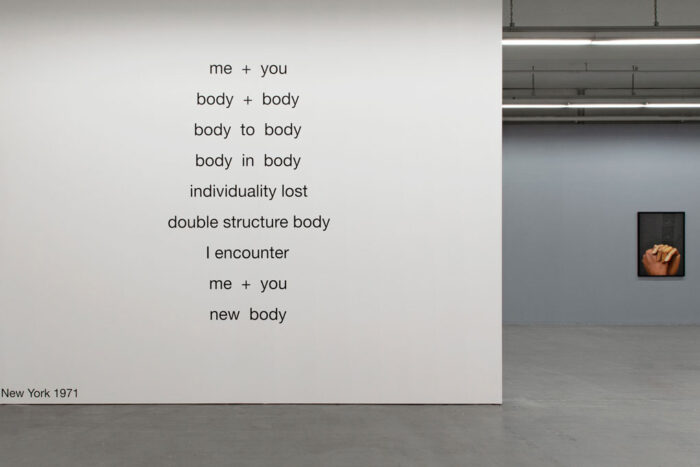

As time has gone by, I have learned to value the meaning of each spoken word as a reflection of a thought. That is why I began to use them together with graphic and pictorial signs to construct artworks and write poetic texts. Without a doubt, I can say that my language represents me and reproduces what I am, as it is the instrument of communication, my tool to communicate my emotions and feelings, especially if we consider all the different media I use to construct my art. Portuguese has been my main language since 1960. However, my erratic speech, far removed from traditional syntax, seeks to evade grammatical rules and insists on being close to the use of other languages—a daring aspiration—as an “exercise of freedom.” Learning each new language always puts me back to the start, to the beginning: to the sounds of the alphabet and consonants. I believe that my nomadic life experience, encountering different cultures and territories, is a solid presence in my spirit, like a metaphorical mirror: “the return to the start.” In a text from many years ago, I wrote: “Whenever I am confused, lost in my artwork, I go back to the start, to the beginning. This movement of constantly returning to the start is present in my works and processes, such as the series of drawings Marcas da Gota (Drop Marks) from 1994 and in the collection of basic shapes modelled in situ that compose the Terra Modelada (Modeled Earth) installations from 1994/2021.” I enjoy naming works. They suggest concepts, ways of thinking that, in a way, precede the construction of the work and, far from being symbolic, are enough to indicate and signify the works.

There are times when you use certain languages and texts—times when you are perhaps writing more than creating sculptures in your studio, or working on videos or drawings, and so on.

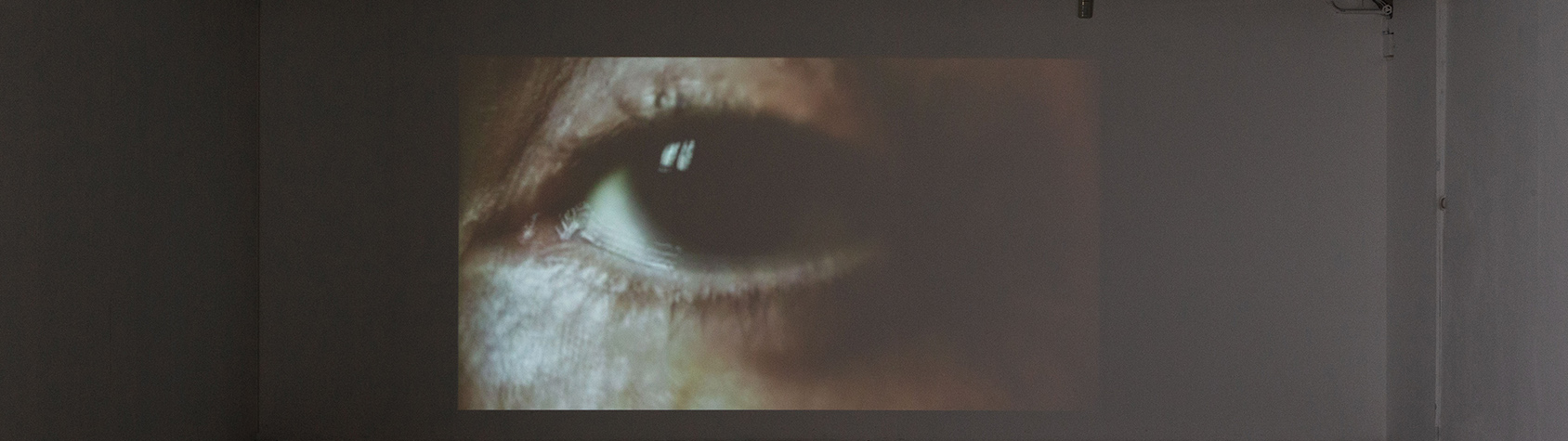

The texts emerge for all sorts of reasons. We must bear in mind that I have worked with art for sixty years and the extent of that time and my curiosity have enabled me to produce work in different media, with a variety of resulting works. I don’t prioritize or value one medium over any other. But, well, the choice depends on which medium would be suitable for the execution of the work to be constructed. Often, just a few words are enough for me to compose a short poem, which might reverberate or stimulate me to develop another different work. In recent years, I have started to create audio works by recording myself reciting my own poetic texts and composing audio landscapes with pre-verbal sounds that feature in exhibition spaces. Some of these works are incorporated into sculptures, such as Estado de Exceção (State of Exception) from 2009/2012, and Dois Tempos (Two Beats) from 2010/2012. I even dare to define the audio works and some of my videos from the series Apreensões (Apprehensions) from 2010 as self-portraits or self-documentaries.

Your multi-layered work, which has grown over many years and decades, includes drawings, photographs, videos, performances, texts, installations, sculptures, and so on. For your exhibition here in Basel, we will display excerpts of texts and poems in the center, alongside films, photographs, and performance documentation, because I believe they contain everything that is in your work. Your clay sculptures, for example, take the form of a thought, a word, a pause, or a phrase. Is this impression true?

It’s true, to construct my work I have used various media, and I tend to say that my work is developed in continuous spiral movements, now moving outward, now moving inward to the central points of interest that nourish the work, such as aspects of everyday life, nature, matter, earth, the body, sounds, concepts, the transcendental, the infinite, and the part. Works emerge that suggest digestion, defecation, the inside and the outside, and the political, all of which is also manifested by the body. One clear example of my sociopolitical works is the photographic series Fotopoemação (Photopoemation) from the 1970s, and the performance Entrevidas (Between Lives) from 1981. These works present metaphors based on experiences, and underline the possibility of a reality consisting of ideas through the use of a body of senses connected by a variety of techniques. A web of meanings is thus formed, creating multiple alphabets of language.

You were born in southern Italy and, after emigrating to Brazil, you returned to Italy much later, in the 1960s, for an exhibition. In the 1960s there was a vibrant artistic moment in Italy: Arte Povera. Artists who were active under this umbrella term included Jannis Kounellis, Marisa and Mario Merz, Giovanni Anselmo, and many more. It was only in Rome that someone like Kounellis, who came from Greece, could find his language of choice (Italian) and develop his first works from there. Was there never an attraction or a desire for you to return to Italy, especially in this creative environment? Your work would certainly have been an important source of inspiration here. Especially in the 1960s and 1970s, when Brazil was suffering under military dictatorship, and freedom of speech and simply being free were both particularly difficult. Why did you prefer to stay there?

I was born in Calabria in 1942. Unfortunately, I am a daughter of the war and of fascism. I was the youngest of ten children in a big, noisy family, typical of southern Italy. My parents were learned people from other times, who had benefited from a great humanist education and valued knowledge and art highly. My father was born in the late 1800s and my mother in the early 1900s. In 1948 the family moved to Bari, in the Puglia region, so that my elder brothers could go to university. I remember my childhood and the post-war years before emigrating to Caracas, Venezuela, in 1954. The first twelve years of my life in the south of Italy were certainly fundamental to my development as a person and an artist. I would even say that most of my work results from reminiscing about the cultures of those lands, such as the preparation of food, working in the fields, the harvests, the singing and music, the rocky landscape with its caves, the bright blue sky and sea, split by the horizon. I say that my most primitive reactions and my character are Calabrian, but that I am far from knowledgeable about Italian art. I have lived most of my life far from my country of birth. After emigrating, I did not return to Italy until 2010, when I started to participate in collective exhibitions. I have always stayed there for just a few days at a time and have never had the chance to travel as a tourist, so I still don’t know that country. Finally, 2010 was also the year that I had my first exhibition with the gallery I work with, Raffaella Cortese. A few years later I started to work with the Hauser & Wirth gallery, which has its main headquarters in Switzerland. Then, in 2018, I had the privilege of assembling a retrospective exhibition, O amor se faz revolucionário, at PAC in Milan, curated by Diego Sileo. I have since returned numerous times, always for work, and always for just a few days at a time. Without a doubt, it was my art that reconciled me with my motherland, although I feel torn for having been so far away for so long.

The São Paulo Art Biennial is an important institution for the whole of Latin America. It afforded me the opportunity to see all kinds of art from around the world and from Italy. This was how I became familiar with the works of important Italian artists of the 1960s. From 1964 to 1981, Brazil was going through dark times under military dictatorship. Despite the censorship, I—like many artists—was able to work and resist. Today, our means of communication have made all countries neighbors, and the COVID-19 pandemic has currently equalized everyone under the threat of death. It concerns me to see the rise of far-right politics spreading around the world. Right now, Brazil is one example of this.

However, my art owes a lot to my shared experiences with Brazilian artists. I think that Brazilian modern art is very strong and relevant, and the contemporary art there is extremely vibrant in its experimentation. My assimilation into Brazil has been a long process, but I can say that working with art has been a curative process for me in many respects. I arrived in Brazil at the age of eighteen, with the heavy and painful baggage of an immigrant. I cherish my strong ties with this country that welcomed me, where my two children were born, and where I built my home.

You just mentioned the situation in Brazil under the military dictatorship from 1964 to 1981. I can imagine that for someone like you, being an artist, a female artist, an immigrant, a woman, and a mother, the situation was not at all easy. Did you never think of leaving? Or, to ask this question in a different way: What made you stay, besides family reasons? Was there an inspiring context, some fellow artists, or friends that provided this kind of exchange despite the political situation?

In 1968, my then husband, Rubens Gerchman, was awarded a grant and we decided to move to New York where he could use it. The grant allowed us to leave Brazil during a difficult period of military dictatorship, where the threat of repression and censorship loomed over us. It could be said that we exiled ourselves.

Rubens and I were entirely unknown artists to the art world and the New York art market. There was nothing strange about that: as well as being new arrivals, we were Latin American, which back then meant the same as being nothing. We did not matter at all to American and European art circles.

In a text from 1997, I wrote: “I decided to assume all the possible destinies towards which I had been traced, without leaving anything out. Being an artist and a woman has been part of one and the same repertoire since the start.” I also felt a duty to address political and social issues. Indeed, the feeling of duty has heavily guided some aspects of my life. I was still very young when I had to take a stance on reality, to strike a balance between my obligations as a woman and a mother and my desire to create art and discover who I was.

Spending almost three years in New York left a permanent mark on me. However, it was hard for me to not be able to participate in the cultural life of the city with two small children and other difficulties exacerbated by everyday life and financial hardship. This situation led to the breakdown of my marriage, and in 1971 I returned to Rio de Janeiro with the children, separated from Rubens. Shortly after, we divorced.

Back in Rio de Janeiro I had to start over from square one. The dictatorship was at its worst point. I felt impotent in the face of that repression and the thought of leaving Brazil with two children became impossible. I urgently needed to find a way of earning a livelihood. Nevertheless, I put my energy into building my oeuvre. Despite the difficulties I had encountered upon returning to Brazil, this was one of the most prolific periods of my artistic career. It was a time of great experimentation, especially with drawing and the so-called new media: Super-8 film and performance.

Your artworks are also instruments of communication for your emotions and feelings, especially regarding the different media with which you construct your art. Do you work with different media at different times, or in parallel at the same time, depending on the topic, or as I previously mentioned, your emotions? Has your artistic approach changed, or perhaps the way you work in general now in times of crisis?

Ever since I left my country of birth, my heart has become one of a nomad, always ready to set up camp in any hospitable land. This is a good metaphor to explain my craving for freedom and my diverse oeuvre. Indeed, the choice of medium to be used for each work depends on my emotions and feelings. At the moment, in this global humanitarian crisis, it is difficult for my aggrieved and saddened heart to nurture my emotions and cite any preferences. However, as an artist, I have the self-conscience that I need in this crisis to find ways to create works that might interpret my feelings in the face of the serious issues that Brazil and the world must tackle.

Within the whole exhibition layout here in Basel we are going to show videos and performances from the 1960s and 1970s as well as more recent works such as Eu sou Eu, which you presented at documenta 13 in Kassel. Reflecting on what you mentioned about Brazil and the dictatorship in the 1970s and 1980s, I was wondering how it was possible to work with performers and realize these performances in public space, as well as to produce them and show them within the country afterward? And as a follow-up question, at that time, it was generally quite early to be working with video and doing performances, too. Was it difficult to acquire all this know-how during this time, to find other performers to participate in them, as well as the possibility of showing them and starting a conversation with them? Most of them are quite strong statements regarding the political situation in Brazil and the role women play within that context.

Art, like every discipline, is selective and very rarely reaches the entire general public. An artist’s work bears multiple readings and there is always ambiguity in how it is perceived by observers, since when regarding an artwork each individual will appreciate it through the lens of their own intellectual, artistic, and political experience. In most cases, this experience does not coincide with the premises of the artist who created the work.

We must bear in mind that, in the 1970s, the arts were renowned around the world for groups of artists who carried out profound renovations of languages through video, photography, and performance. A key role was undoubtedly played by female artists in particular, who also created artworks with political undertones, expressing resistance and challenging the establishment.

Visual artists during the military dictatorship in Brazil (1964 to 1981) produced works that used metaphors to avoid direct, explicit political pamphleteering. We found ways to sidestep the censorship, motivated by the drive to resist it. However, these agencies of repression gave surprisingly little importance to certain artworks, such as my installation Arroz & Feijão (Rice and Beans) from 1979, and Entrevidas (Between Lives) from 1981. Both of these works are heavily charged with social and political meaning. Fortunately, I don’t think the national security law, the dictatorship’s bible, considered artists and their works as dangerous. After all, at that time, access to museums was limited. I believe that the agencies of repression failed to understand the subtleties of the metaphors used in these works. I also think the poetic and metaphorical creative process is not written in the military codes and, therefore, visual artists enjoyed a relative degree of freedom, despite the fear. This was quite different to what happened to actors and composers of popular music who directly and verbally expressed resistance and a rejection of the government in power, and were heavily censored as a result.

From the 1980s onward, in the wake of the dictatorship, efforts were made to raise the profile of museums and large numbers of people visited exhibitions. Consequently, even contemporary art productions enjoyed greater exposure to and understanding by the public. However, over the past two years, a growing number of Brazilians, especially intellectuals and artists, are concerned about the increasing dismantling of education, culture, and art by the government.

Many of your videos, photographs, sculptures, and texts reflect this period of trauma, of living in a dictatorship and its latent violence toward human beings and especially women. There is one thought that I have had during these months of the crisis, where I keep asking myself if the pandemic will really change our perception of what we see. Here in Europe, for example, and especially in Switzerland, most of us have never had the experience of being locked up before, of being forced to stay at home, being isolated, and so on. Perhaps this crisis will now usher in a kind of empathetic experience that helps us to read many things differently from our current perspective, including, perhaps, your performances, texts, and artworks. Do you think this could happen?

History repeats itself. However, we need to make the right choices in the present that can point us toward a more humane future, away from violence and barbarity. Nature repeats itself in diseases, in natural disasters. It just is, it exists. Humans have not learned how to behave adequately with different natures, both their own and that of their surroundings. We are certainly in times of profound change. The COVID-19 virus is constantly mutating into new variants. The earth has also become a mutant in its geographic and climatic configurations. Only humans remain fossilized in their prevalent conformism and beliefs of profits and progress at any cost. Humans are responsible for the misery spread around the world and the violence committed by humans against other humans. Finally, as artists, we are left to take responsibility for the truth of the creative act as political action. I believe we urgently need to go back to the start and revitalize the overarching forces of sustenance, those immutable values in the natural dimension—water, air, fire, and earth—and retrieve the culture of nature, the naturalization of culture that enables, as Edgar Morim says, the foundation of a universal equilibrium.

How is the situation for you now, despite the current crisis—do you have opportunities for exchange with other artists when needed?

My move to São Paulo, leaving Rio de Janeiro in 2005, had a deep effect on my closest relationships with artists from Rio. When I arrived in São Paulo, I was sixty-three years old, at the peak of my professional career, which led me to do several exhibitions and trips abroad. The time I spend in the city is dedicated to developing my work. I enjoy spending hours in my studios, but then I am away from the social life of the city, which has made it difficult to meet new generations of artists.

Now, with the scourge of increasingly far-right politics in Brazil, and in the face of the violence in the country, where so many young people and women are being murdered every day, it has become imperative to be with others and to establish dialogues. The social isolation imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic has without doubt brought to my mind all these questions related to this huge crisis. In an attempt to establish dialogue with the young critic Paulo Miyada, we proposed a quarterly digital publication that we named PRESENTE (PRESENT).

I consider this online project, which is to be published in Portuguese and English, an important endeavor. It will consist of correspondence, texts in other formats, and productions generated through dialogues between two or more people. The main focus is the field of visual arts in Brazil. This collective project takes on other senses, such as mapping our feelings. PRESENTE will be launched online on April 21, and you will be one of the people invited to access it.

This project is incredibly strong, and while doing this interview, I was able to read the magazine and also discuss with you how to best integrate the publication into the exhibition here in Switzerland. On the other hand, looking at the situation in Brazil right now from a political, public health, and ecological perspective, being separated and at a distance from each other, where people cannot meet and art cannot be perceived, perhaps a magazine, free of charge and accessible to everybody, is best placed to explore language through texts that reflect, in a very direct way, the thoughts and concerns of this exact moment. Do you see these texts—which are conversations, articles, and poems at the same time—as part of your artistic approach, since they are just as political, poetic, artistic, and informative?

The project PRESENTE was born in late 2020, the first year of the pandemic, with thousands of deaths despite social distancing. This situation further exacerbates the ecological negligence and abandonment of culture and art by our government. This quarterly digital publication came about from my need to escape from enforced isolation, and my desire to be and communicate with others.

At the start of 2021, while replying to a wonderful letter from Paulo Miyada, I realized that letters between friends and artists could represent a strong means of expressing our feelings, forming a kind of art. Thus, together with Paulo, we kick-started this publication in Portuguese and English. It features correspondence, letters, other texts and productions created in dialogue between two or more people in the field of visual arts, primarily in Brazil, but we are also open to submissions from abroad. The word PRESENTE refers to now, the subject matter of the content, but it is also a synonym for a gift and, as such, the digital format of the magazine can be accessed free of charge.