I Promise You The Sea Will Unite Us Again

An inaccurate review of the XI Busan Biennale

This piece was previously published in Italian on Exibart #125, and translated by Emma Mattei.

Premise: What follows is not intended to be a comprehensive review of the 11th edition of the Busan Biennale, but rather a recounting of my experience at the exhibition Seeing in the Dark, co-curated by Vera Mey and Philippe Pirotte. I arrived on a hot August day, far from the glamour of the opening, thanks to a high-speed train that allowed me to travel to Busan and return to Seoul on the same day with just a few hours to take in the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Museum of Modern and Contemporary History and 1918 HANSUNG 1918. The tropical heat kept me from stopping by the Choyang House, opting instead for a series of iced American coffee (the unusual choice of iced American coffee due less to personal taste—this was more of an attempt to immerse myself in local culture and sip on a popular drink choice).

In addition to my own thoughts, you’ll also read the perspective of co-director Vera Mey, whom I interviewed thanks to Hiraani Himon, the director of Te Tuhi (a remarkable contemporary art space in New Zealand) and former deputy director of South London Gallery, as well as the Italian curator and researcher Anna Castelli, who connected us. The perspective from which I’ve written the following is not that of a journalist, but rather as a curator and colleague. The theme of the 11th Busan Biennale is, in fact, closely aligned with a curatorial section of the Malta Biennale (Insulaphilia), that took place 9,000 kilometres away: Pirate Utopia.

As a diligent visitor, before entering the exhibition, I paused to read the educational panel written by the curatorial team. Thankfully, this time they were merciful—no lengthy scrolls or grandiose flights of fancy. The decentralised exhibition Seeing in the Dark draws parallels and explores connections between pirate enlightenment and Buddhist enlightenment. I’m stunned; I would have never dared to make such a comparison. This comparison made the early-morning wake-up call worthwhile if just to encounter this divergent thought.

The Buddhist monastic way of life is presented as a complement to that of pirates, where nomadism and resource redistribution form part of both worlds. The figure of Buddha, portrayed as “an empty signifier” who aims for a self without place, is like a deserter or pirate. In pirate communities, decisions were made through negotiation and assembly in a council of the most capable, regardless of culture or race, and just as in monastic settings, the rules for managing communal property are maintained through regular meetings. European Enlightenment is conventionally associated with light and the belief that knowledge emerges with visibility. Here, however, pirate and Buddhist enlightenment offer new transparency and dissimulation, both necessary to escape a system of hyper-surveillance. At a formal level, this metaphor is immediately clear upon entering the first hall: the monumental diptych by artist and Buddhist monk Song Cheon faces Eugene Jung’s metallic installation, a sculpture composed of a series of collapsed drones that obstruct the view and interfere with the enjoyment of the monastic work.

The co-director explained to me that the parallel between Buddhism and Piracy allowed the local Korean audience to connect with the concept of Pirate Utopia. Once again, using a familiar concept proved effective in introducing new ideas.

The Pirate theme of the 11th Busan Biennale is honoured to be presented with the scientific backing of the David Graeber Institute, an essential theorist on the subject (1961–2020). Curious to understand how this collaboration came about, Vera Mey explained to me that the director of the Institute, Nika Dubrovsky, Graeber’s widow, is one of the artists in the exhibition, so the exchange of knowledge was able to bypass rigidity and red tape. The system of mutual stimulation and exchange was fluid and organic—from curators to artists, from scientific consultants to curators, and vice versa—in a collaborative rhythm that was less formal, more focused on content rather than the pedestal from which it was conveyed.

In addition to the exhibitions, Seeing in the Dark features a robust program of collateral activities. Specifically, the curators placed great emphasis on music and the role of sound within the pirate utopia. Curator Vera Mey explained to me that it was essential not only to inform the public about the themes but also to evoke emotion. In this sense, music is undoubtedly the most effective medium to connect with the audience on a visceral level, and the Biennale has served as a platform to support the growing local art scene.

Let’s now get to the point, to the heart of a Biennale: the artists. As with every biennale, there are many names, so I’ll take the liberty and responsibility to only mention those that impressed me the most, who, despite the heat of the Korean tropical summer and the early wake-up call (you’ve probably guessed by now that I’m not exactly a morning person), held me transfixed.

One discovery was the Chinese artist Han Mengyun and her first feature film Night Sutra (2024), a three-channel video set within a Dong textile installation that alludes to the form of an open womb. The Sanskrit word śarvarī means both night and women, with the work developing this dual meaning by exploring natal labour, generational motherhood, postpartum depression, bodily suffering, shared transcultural heritage, as well as the religious and literary representation of women (including a critique of misogyny in Buddhism, a rarely discussed topic). The work includes footage from Dali Dong village in China, to Phnom Penh and Siem Reap in Cambodia, and in Europe from London to Vevey, Switzerland. The textile installation surrounding the video recontextualises darkness through the use of a shining traditional fabric made by the women of the Kam/Dong (侗 族) minority in China, who venerate the colour black for its reference to the darkness of the womb.

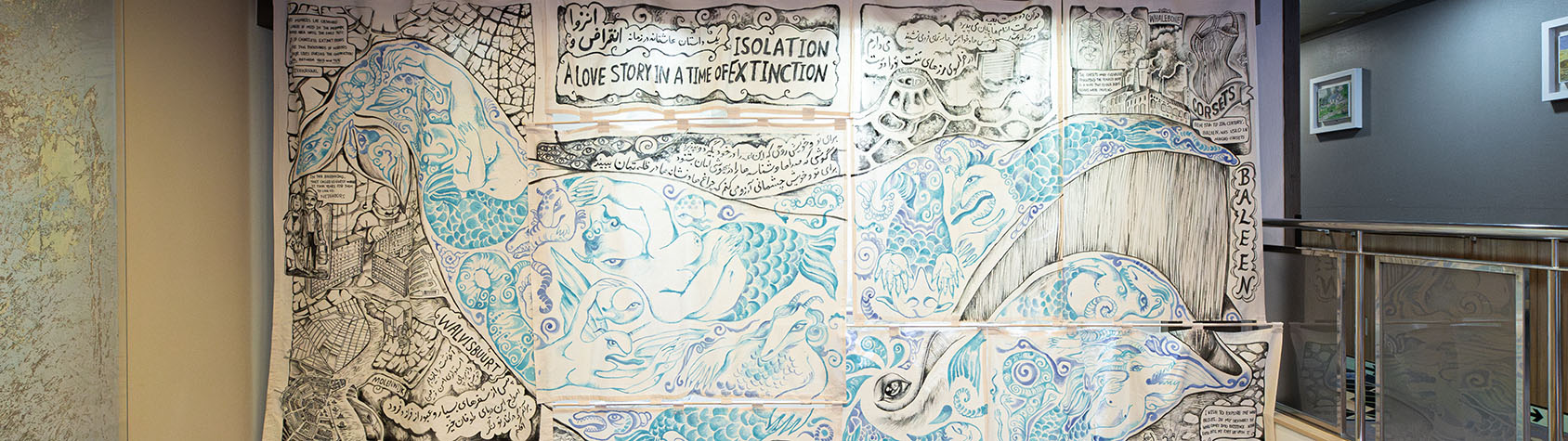

Truly moving is the artwork Continuous Cities (2024), by Golrokh Nafisi and Ahmadali Kadivar. Composed of a series of handmade fabrics and embroideries, it is displayed as an installation of curtains and flags suspended from the ceiling. This artwork is a long-term ongoing project that began in 2017, providing a sort of imaginary map combining travel stories, drawings, slogans from local revolts, and love song lyrics. Mey explains that it was essential to include strictly analog works in the Biennale, to create a contrast with local expectations and easier associations between piracy, digital technology and cyberpiracy. Like many of the more potent works, this one is the result of a lengthy residency, where the artists spent several weeks in Busan, exploring the city and frequenting the markets—essential to the economy of this maritime city.

As often happens with sincere artistic research, the exhibition also includes a spontaneous element, most likely added at the last minute. Thankfully, there are still curators who are willing to embrace artists’ intuitions, even when they aren’t planned, even if they don’t fit the “right” layout, but still radiate a light of their own. As curators, it’s our duty to trust the instincts of artists. In this case, the late addition, perhaps somewhat makeshift in formal terms, is a letter printed on plain paper that I found so moving, I felt compelled to translate it for you and share an excerpt:

“The banner behind me is called ‘Farewell in Busan.’ This banner represents twenty-one days and nights of our life in Busan. During this time, the sun rose twenty-one times from the east side of the sea and set behind the mountains at the end of Dadaepo Beach. Between these sunrises and sunsets, Busan welcomed us, a city known for embracing many refugees in its history. In the alleys of Busan, on its beaches, in its restaurants, cafés, and streets, we felt the mark of farewells. Perhaps because we too come from a place of farewells—farewell to our homeland, farewell to our language, farewell to our history, farewell to our families, friends, and companions, and finally, farewell to the revolution. In the history of Busan, many workers were forced to say goodbye to their families at the port, waving from the ships and shouting, ‘We will meet again at the 40 Steps; I promise you the sea will reunite us again.’ This is not just the story of Busan; it is the story of many of us. Many of us, in our dreams and across impossible borders, wonder if we will meet our families again. From the Mediterranean Sea to the Yellow Sea, from mountains to mountains, from rivers to rivers, from East to West, we carry the pain of separation.

This is the story of the banner we hung today on Eulsukdo Island, an island where many birds once said goodbye because we took their lands. We humans, with all the stories of farewells we have lived, have also driven them from their homeland.

Tomorrow we leave Busan. On the train heading north, we will remember all those who are still waiting for borders to open so they can see their loved ones after long separations. We will leave Busan with the dream of the fall of walls, the end of empires, the end of colonial borders, and of the cold and hot wars. We will leave Busan, whispering to ourselves: See you again at the 40 Steps; I promise you the sea will reunite us again.”