I love you, Dick

or “I Love Dick” and the ocean in between

Ruth is a collector of writings, a site dedicated to grey literature, unpublished and experimental texts. Conceived by Manuela Pacella, was born from the pleasure of writing and reading. We are very glad to host a text each month, selected from one of the sections of the four-headed Ruth: Yellow Dog, Hungry Ghosts, Free Spirits, Brain New.

This month we chose from Free Spirits I Love Dick, or “I love you, Dick”? by the young and talented William Paolo Guarriello, originally written in Italian and translated in English especially for us.

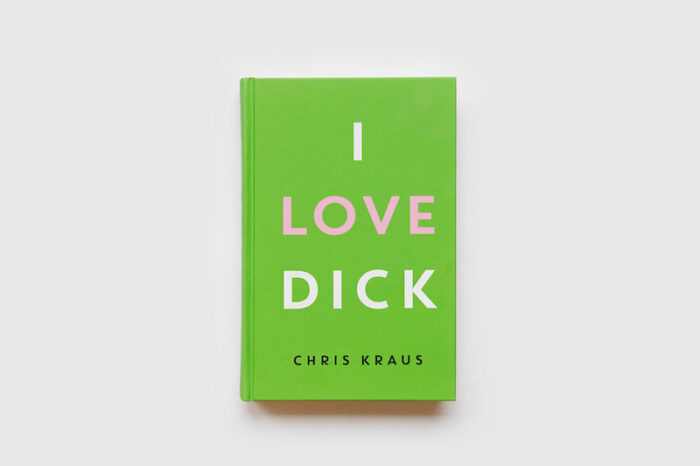

Someone said we are animals. Well, social—but still, animals. It is not true; at least not completely. If we were simply animals, there would be no point in talking about progress. That wouldn’t even exist as a concept, it’s clear. The lions are not debating how to become more civilised towards the gazelles or how to break down the law of the strongest when choosing which lioness to mate with. After all, the word “civilisation” presupposes the existence of a community of citizens. Humans are citizens, not lions nor gazelles, although it would be fair to ask which one of them is better equipped to cope with the world. In any case, to talk about progress means—not surprisingly—to talk about love. It means as well to talk about happiness which, according to the Constitution of the United States of America, is a fundamental right. This reality, which might be disturbing for the sensibility of some social animals, is also unfolded in a 1997 novel written by a proper American. Her name is Chris Kraus, she is a filmmaker and the protagonist of I Love Dick.

One thousand nine hundred and ninety-seven: divorce is legalised in the Republic of Ireland, Titanic hits the box office and Elton John performs Candle in the Wind at Lady Diana’s funeral. Symbolic curiosities? No. It is simply interesting to note how these events could have carved out a place for themselves in a few chapters of the book if only it had been published a couple of years later. This is not so much a matter of speculation – quoting and exploiting events without analysing them with the right intellectual honesty is a sadly common practice in all forms of communication – but rather of humanistic relevance. Undoubtedly, I Love Dick does have this relevance. It is also astute in the way it acquires it and brings it to the eye of the reader. It does so through an epistolary format that is as dynamic as it is reflective, and can be defined as “ultra-diegetic” for it is inextricably linked to the dynamics of the story it is composed of. Letters, faxes, e-mails, notes and reflections unfold in a stream of consciousness reminiscent of Joyce, dragging everything and everyone into a chaotically ordered, almost rational vortex at the centre of which stands the battle of the opposites: love and hate, necessity and superfluity, beauty and ugliness, strength and weakness.

But does I Love Dick really tell a story? It is quite relative, since in this case the Aristotelian concepts which are there, count very little. Chris is with Sylvère, then develops a crush on Dick, and the rest is an unorthodox journey through the uncertainties of a deeply disillusioned woman who feels out of place (and how many out-of-place princesses there were in 1997, and how many there are today). With certainty, this yes, tells The History. Because Chris Kraus, ultimately, writes about a universal human condition. Her writing is a splendid feminist portrait and at the same time an honest analysis of the man-woman, woman-woman and man-man relationship in the modern era. There is no demonisation, no malice and no demagogy. But there is love. Don’t they say that love attracts opposites? Well, in this case you could say that love is in these opposites; even more if you grasp the words with a less enlightened and more romantic gaze. The point is that it is hard to deny that this portrait is, among other things, a tribute to the freedom of being in all its most intimate facets, no matter how one approaches it. Art is one of them, certainly not an insignificant one, given its centrality in the development of the lives of the three protagonists of the story, who are perfectly positioned at the ends of a pyramid destined to collapse on itself. It will do so not only because of the structural flaws that characterise each extreme, which are incompatible with one another (despite the desire to convince oneself otherwise) but also and above all because the foundations are and have always been rotten. Most likely they always will be. This, too, is I Love Dick: an account of the fragile constructs (inescapably hierarchical, and this is a point Kraus repeatedly hits) we’ve built up to keep us at ease, that eventually take us apart. Unfortunately, art is not immune to this truth. It is extremely difficult to talk about it without falling into a limiting rhetoric, and as a good artist, Chris Kraus knows this well. In fact she doesn’t write anything that could hide the unhealthy intention to impose an univocal vision of the world and its things. By filtering through a reasonable emotionalism she shows and analyses, although hers is still a subjective view—a rear window. And through the windows of 1997, one could see a world in the preliminary stage of a radical change, in the wake of the great progressive debates that characterised the last portion of the 20th century. Twenty years have passed since then, according to some, our global tribe has changed more outwardly than inwardly, and I Love Dick can be found on the screens of personal computers and smartphones. As a book? Also as a book, but for a more general public and an avid devourer of moving images, it has taken the form of a (streaming) television series.

In the end, even a work so obviously unsuitable for live action has managed to get its own television adaptation, and—as it always happens when a transfer from one media to another is carried out—the filmic restitution of the original is far from the concept of “fidelity”. Not so much because the infamous story, or plot as it may be, is not exactly the same—any scriptwriter would find it difficult to transfer such a vast and stratified complex of information as that of I Love Dick to the small screen. It is the very spirit of the work that has been impoverished. What you see on the screen consists only of the most superficial layer of Chris Kraus’ work, and perhaps not even that. It is such an extreme, deformed and distorting synthesis, at times annoyingly banal, that when it’s over it leaves not much more than a void in the heart and the mind of the viewer. It is not enough, for instance, to make sex a vital element—as it is in the novel—if it is never explored in all its philosophical and psychological component, even though the average viewer might find it sufficiently interesting (and exciting). Even the references to pop culture and the whole artistic macrocosm are not enough to make this product deeper than it really is. Chris, Sylvère and Dick—the “actual” ones – are not aristocratic debaters of art and philosophy: they are art itself, with its vital flame now drained by the chill of everyday life, and philosophy, fallacious and perhaps insignificant. So the problem lies right there, in the characters, who in their visual counterpart are transformed into excessively clichéd figurines bordering on the demagogy that Kraus so shrewdly avoided, starting with the Dick of the title (played by a Kevin Bacon who is far too stereotypical in playing a part that was already far removed from the original).

Eventually, the series created by Sarah Gubbins and Jill Soloway is nothing more than a colourful box deprived of its contents; an avoidable and sketchy portrait of something far more complex and sincere. As the final credits roll, one might wonder whether the much-discussed and much-vaunted progress, including in the depiction of society and its performers in the contradictory art industry, is really happening, and if so, to what extent. Because this, rather than I Love Dick, is a “I love you, Dick”. There is an ocean between these two visions. An ocean that could say that, yes, maybe someone didn’t understand much of the whole thing at all.