How To Make A War Film On No Budget

Lessons in economy and ex-stasis from IFFR 2025

Tijana Mamula went to the 46th International Film Festival Rotterdam in search of ideas for a couple of low-to-no-budget war films. What she found on the way was a cinema bursting at the seams.

I don’t know if it’s just me, or the films I’m choosing, or if there really is something unusually incontinent about the state of cinema in Rotterdam. It keeps spilling over, across its borders, reaching through the screen, into the audience, into other art forms, other media, other realities. Like it’s tired of itself, or something. Or confused. Or suddenly disobedient; tired of obedience. Bored of expectations. Or just bored. Or interested in something it glimpses happening beyond its confines, over there. Curious. The words “identity crisis” keep crossing my mind.

Half the time, it’s kind of hard to figure out what’s happening on the undulating, unfixable screen, as though the films were subjected to some sort of conceptual moiré effect.

I suppose it’s already there, or a trace of it, on the first afternoon, when I lean into my guilt and spend two precious festival hours on a screening of Payal Kapadia’s All We Imagine as Light (2024; my excuse is that Kapadia is there; where else am I going to attend a Q&A with her?). In this poetic, Mumbai-based drama about the intersecting lives of three nurses, the youngest of the protagonists, Anu, keeps pinging her boyfriend. The messages appear written on the screen—very simply, right in the middle of the frame—as though the cinema screen were her screen, despite the fact that she’s on it. No bubbles or boxes or any cleverer differentiation between what she’s seeing and what we’re seeing, which, though it may be a graphic decision (Kapadia’s film is generally tasteful and economical), does already start to blur the boundaries between cinema and everything else. Meanwhile, her older roommate Prabha keeps fiddling with her phone (which keeps failing to ring, or to afford her that longed-for communication with the elsewhere her husband inhabits), and also with her windows, and sometimes with both at once—there’s an exquisitely beautiful nighttime shot of Prabha sitting in front of her window, reading by phone-light; behind her, the bright lights of the big city, and its millions of other windows, which, from this distance, may as well be phones. Conditioned by the succession of all the other phone screens and architectural openings and on-whose-screen? texts, this ends up being an image of so many windows onto the world framing each other that you forget which starts where and what the difference is anyway. And where you are, exactly, in all that.

So when, towards the end of the film, Prabha’s husband materializes in the form of a stranger she saves from drowning, a man who washes up on the shore from an unknown elsewhere (I’m reminded of Homer, the dead sailor husband in Fritz Lang’s equally threshold-treading Scarlet Street; I wonder if it’s a reference?), and we can’t tell how much of the scene is really happening, or if it’s happening it all, the uncertainty doesn’t feel as weird or as off as you might expect it to. That Kapadia didn’t feel the need to resolve this doubt, any more than she felt the need to signal Anu’s texts, was one of the things I liked about this mostly tame, measured film.

The next day, that same uncertainty crops up in The Radiant Screen (Ine Lamers, 2025)—a heavily Marker & Tarkovsky-esque essay film that tackles the question of how to represent a closed city (the Russian city of Ж, or Zheleznogorsk). It finds a solution in, among other things, having seeming actors deliver seeming voiceover excerpts, only to lead us, gradually, to the realization that the actors aren’t actors but locals, and their monologues aren’t the fruit of the director’s imagination but rather their own testimonies…I think. There are so many degrees of separation between the ostensible reality of Ж and the director’s reconstruction of it that it’s hard to tell whether the city even exists, never mind how the various audiovisual representations of it relate to each other and where they meet—a difficulty that seems, again, to be the point.

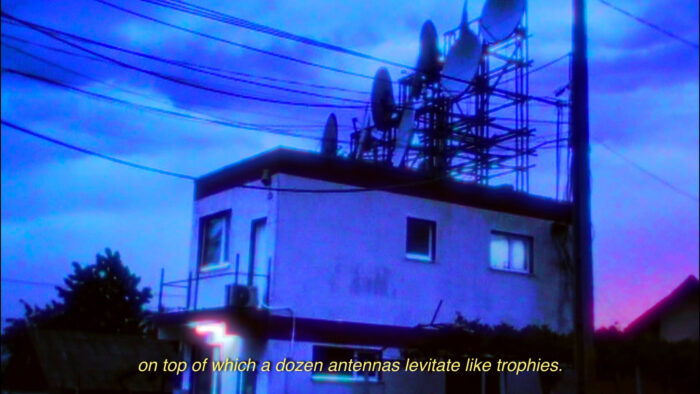

In the same shorts program, Surge of Transference (Geo Barcan, 2024), a bright and unabashed Gen-Z mockumentary about the advent of internet in Romania (“the totems of my childhood are MTV, mud and loneliness. The kind of loneliness that makes people talk to statues,” Barcan quips, and I chuckle), employs the same fluidity in pivoting to a sci-fi fable about a postapocalyptic utopia where the water that’s submerged humanity acts as a carrier, a vector of telepathic communication. The neon-techno aesthetics flatten out the film, so that the telepathic underwaterworld seems to operate on roughly the same level of reality as the universes opened up by peer-to-peer sharing in the mind of a lonely suburban teen riding out the last, post-death days of Eastern Bloc communism.

Still, it’s not until that evening that I start to be taken aback by the sheer unruliness of the cinema congregating at this festival already known for its programming of unruly, uncategorizable films. One of the focus sections this year is a retrospective of Ukrainian director Sergii Masloboishchykov, and I go to a double bill of two mid-length TV documentaries: …from Bulgakov (1999), an experimental biopic, if you will, of the famous author, and Two Families (2000), a curious tale about the connections between the director’s ancestors and those of Andrei Tarkovsky. I’m in a rush and not aware, initially, of the films’ dates of production, so when 1999 comes up in the (Ukrainian) credits of …from Bulgakov, I’m confused. Is there archive material here from 1999? Maybe the footage of the Bulgakov museum? Or perhaps one of the narrating voices? Then I blush—like anyone’s looking at me or could read my mind if they were—embarrassed to have sat there for thirty minutes thinking how new it all felt and looked. (“Finally, some fresh ideas!” I’d scribbled in my notebook.)

The film starts out chaotic enough, with two voiceover narrators talking over each other, the heavily filtered visuals (of the Bulgakov museum, or a model reconstruction of the Bulgakov museum, or both?; Bulgakov family photos), made to look not so much like silent film footage as a post-video parody of silent film footage, competing for spectatorial attention with text that appears all over the screen, sometimes still, sometimes moving, in various directions, not always legible. It occurs to me that I’ve never seen a film that felt more like a collage, an actual physical collage, than this. The two narrators are Woland, the character from The Master and Margarita, and a guide at the Bulgakov Museum. At some point, little Mikhail appears in the footage of the house museum, three or so years old and accompanied by his nanny. So far, so interesting; but unsurprising. Then the guide interpellates them. The nanny had better be careful, that’s the most important child she’s ever held, or will hold. That child will be known all over the world. He’ll be remembered longer and better than the current tsar. The nanny looks at the screen, replies to him, to us. She’s skeptical, perhaps a little irritated. She laughs it off, goes back to the business of tending to Mikhail, with no particular care or reverence. And so with every frame and every line of dialogue, the anarchy builds, chipping away at your need for order, for genres and artwork/audience distinctions and ontological positionings, until you lean back and accept the film for the chaos of possibilities that it is.

Later that night, I try to catch up by streaming from the video library and chance upon one of my favorites of the festival. It’s Hemelsleutel (Key to Heaven, Digna Sinke, 2025). Lessons in economy and ex-stasis abound. It’s a narrative feature about an unmade narrative feature, a kind of if-I-were-to-make-this-film-here-is-how-I’d-do-it that actually ends up making the unmade film, albeit in this other, probably more interesting form. The unmade film is about Lea, a photographer documenting the energy transition in the port area of Amsterdam and its effects on the local landscape. It’s also about Lea’s past, specifically her close friendship and correspondence with a certain Boudewijn, who ended up taking his own life. So, it’s about that distant past, and the more recent past of Lea trying to work on her project while falling in love with one of the civil engineers tasked with guiding her through the power plants, all told from the present of the protagonist’s (Sinke’s?) ruminations on her unrealized screenplay. On one of her walks along the changing shoreline, Lea stumbles upon a corpse. The corpse reminds her of Boudewijn. Ah, therein lies the connection between the two pasts! There are obvious echoes of Blow Up, but that’s not the interesting part.

The interesting part—or at least, the core of the interesting part—is that the film is entirely composed of exactly four kids of image. There’s the mostly documentary-style footage of the energy transition: the port, the plants, etc.; sometimes, very rarely, a character enters the frame, jolting us both out of that semi-documentary dimension and out of Lea’s POV. There’s a basically unchanging, static shot of Lea’s living room: sometimes at night, sometimes by day, but always framed from the same distance and angle. There are close-ups of the actors, delivering their lines to the camera, presumably in a studio, or perhaps simply someone’s house, against a brightly day-lit, out-of-focus background; detached from their surroundings, they’re easily imaginable in the elsewhere of the film’s imaginary plot. Finally, there’s the odd flashback to Lea’s youth, with her husband and Boudewijn, signaled in black and white. That’s it. Every image is beautifully composed: careful, measured, balanced. As Sinke’s narration explains, her protagonist is a perfectionist; her images could look no different. Despite its obvious indebtedness to the likes of Marguerite Duras, Chantal Akerman, Chris Marker (is it any wonder I like this?), the film doesn’t feel in the least derivative or stale. I thought it was made by a person in their thirties or forties, so was, again, confused by the sporadic appearance of an elderly narrator, who I thought must be an actor but turned out to be Sinke herself. The film’s ideas are crystalline, its complex plot—essentially, the meanders of memory across the archeology of a lifetime; complex is an understatement—rendered as fluid as the bodies of water the film keeps returning to. The “unrealized” movie running alongside the realized one is evoked in so much detail that the interplay between the two—like the interplay between documentary and fiction, actor and narrator, screenplay and life, memory and fact—runs to dizzying depths, or heights. This too manifests as an image and a plot point, a crucial one, as Lea insists, to the engineers’ anxious dismay, on ascending to ever higher vantage points. The view is never, she keeps saying, far enough from the ground.

The next morning, I rush to see Le deuxième acte (The Second Act, Quentin Dupieux, 2024), in need of some light comedy, unaware that it’s already playing on MUBI and definitely not expecting to find it a kind of contemporary update of Masloboishchykov’s fourth-wall extravaganza. The world’s first AI-directed film—the plot goes—is a self-reflexive French chamber comedy starring Vincent Lindon, Léa Seydoux, Louis Garrel and Raphaël Quenard as self-denigrating caricatures of themselves. Even the premise is meta. Here too, though, what I really like is the tipping point. There’s an extent to which the back and forth between acknowledging the fiction and not acknowledging it remains anchored, the two sides of the screen discernible as such. The actors talk to each other, forget their lines, address the camera, argue (Quenard’s homophobic rant is clearly a joke, but is Garrel’s cringe reaction to it also?), return to the ostensible script for a few lines, before slipping out again, and so on. But then, somehow, almost imperceptibly, the film tips over, and enmeshes you in a metanarrative nowhereland, with no coordinates. About halfway through, you’re no longer sure where the film-within-the-film ends and where another version of it begins, before yielding to yet another, and another, potentially ad infinitum. Not to spoil anything, but this indeterminacy extends to and culminates in the film’s ending, which also, somehow, brings you back to reality. Or reminds you that despite all the fictions and the meta, the real and its horrors do exist.

More hybrid comedy ensues in Tiger Award winner Fiume o morte! (Igor Bezinović, 2025), about the 1919-21 occupation of the Croatian town of Rijeka by Italian author and Fascist Gabriele D’Annunzio—a serious documentary with a light touch that delights in its own processes and wears them on its sleeve. I was a little thrown by the film’s blithe obliviousness to Croatia’s own fascist history, but I liked its easy, resourceful inventiveness. Can’t find the perfect non-actor for D’Annunzio? Cast nine of them! That key historical location is now a hair salon? Hire some furniture and stage it back into a tavern! Ask the owner to help. Film her doing so. Don’t have enough archive footage? Re-enact a bunch of photos! And so on and on.

A similar mix-and-match of past and present locations, unlikely castings, slippages in and out of history also defines La durmiente (Maria Inês Gonçalves, 2025), one of the Tiger Shorts winners—although La durmiente, about Beatrice of Portugal’s arranged marriage, at age ten, to King John I of Castile, and by extension about the enduring issue of child marriage, is more pared back and restrained, less exuberant, its historical outrage-cum-contemporary social commentary filtered through the interiority of a personal experience, with all its attendant sadness. Where Fiume o morte! seems largely uninterested in its subject’s experiences or motivations (approaching them with, if anything, a kind of tautological “he’s a fascist because he’s a fascist because he’s a fascist”), La durmiente appears driven by a very simple, genuine interest in what it might have felt like to be the ten-year-old princess of Portugal enduring her exile into Castilian queendom. Somehow, it finds the relics of those feelings in the film’s physical spaces, so that for all of its fictional paraphernalia, it lingers almost as a documentary about a place (those walls, that path, this rock) and the dreadful memory it preserves.

If IFFR 2025 taught me one thing, it’s that spectatorial imagination, and anything that can be done to aid it, to just nudge it in the right direction, is far more powerful than the most meticulous of realistic staging. Fiume o morte! demonstrates this again and again by having the actors inhabit historical spaces, with no care for their changes since 1920, nor funds wasted to clear them of passers-by, without this ever truly impacting our ability to imagine or mentally inhabit the spaces as they once were. The period costumes (being generally cheaper than clearing and dressing entire locations), do enough of the work for our mind to fill in the rest. This is all the truer in Grand Tour (Miguel Gomes, 2024), which further benefits from being shot (mostly) on grainy, black and white film stock. Between that, the casually accurate, nonchalantly worn costumes, and the few historically plausible interiors, Gomes successfully evokes the year 1918; the film’s contemporary exteriors do little to take us out of the pretense of finding ourselves in Rangoon, Bangkok, Saigon, Shanghai, some one hundred years ago. “If I succeeded,” Gomes has said in an interview, “it’s because I wanted to prove that throughout the history of cinema we’ve spent too much money [my emphasis] trying to make the viewer believe in things that they’re already capable of believing so long as they accept the pact of fiction.”

Here, more so perhaps than in Fiume o morte!, the blatantly contemporary settings also serve to flesh out the film’s anti-colonial critique, its aesthetically rendered sense of may-as-well-be-the-1920s reiterating the core point that, yes, as far as the West is concerned, it may as well be the 1920s. (I’ve actually no idea if this is what Gomes intended, but it’s how I’m choosing to read it.) And the critique, of course, doesn’t just use the cinema as a vehicle, but encompasses it. Cinema’s globetrotting romances and exotic representations—as cheap and inauthentic now as they were then—are part of the colonial wreckage. As Edward makes his way through Asia, fleeing his fiancée Molly, while Molly, steadfastly, monomaniacally, follows him, Grand Tour’s methodical returns to traditional puppet shows (one for each leg of the tour), reflect back to us the contrivance and two-dimensionality of the images we see on the screen, signaling them as a construct that’s about as close to reality as shadow theatre. There is absolutely no difference between our suspensions of disbelief, Gomes seems to be saying, and those of the ethnic and racial others we relegate to the other side of the screen. At the same time, these various excursions into Eastern theatre hold up a mirror, in which all we see is our own incomprehension—an incomprehension that extends far beyond this or that instance of not-quite-to-our-taste entertainment. Like the (cinema) history it critiques, Grand Tour is a film constructed along the we-look-at-them axis and embedded in the elaboration of fantasies that enable venturing into the shallows of foreign lands and cultures to ravage whatever we please. This, in the end, is the “Grand Tour” and the romantic tragedy that guides it: a voyage through the blind arrogance and wholesale failure of the West’s colonialist dream. It’s also—and I loved this; almost too heavy-handed, but I loved it—in Portuguese. Despite the characters all being English, the entire film is inexplicably, unapologetically, spoken in Portuguese. Take that, Hollywood! Viewed through Gomes’s so-sarcastic-it-almost-passes-as-earnest lens, our history is a farce; but a farce that hurts.

In the shorts program, I find Commute (Henry Hills, 2024) echoing with a similar critique disguised as nostalgia. It’s a montage of shots of rail tracks filmed from moving trains, rhythmically set to a variety of songs and instrumental pieces, from Bérlioz to Duke Ellington to Kraftwerk. All of them reminiscent of cinema. Or better, the musical tracks reminiscent of cinema and the movements of its history; the train tracks (somehow always dusty, often sunny) reminiscent of a different kind of movement, a westward expansion, brutal and unrepentant. The whole a kind of abstract symphony of the history of Hollywood, the violence of its representations intersecting—physically, relentlessly—with the violence of the empire that made it.

More lessons in radical economy crop up in Goyo Anchou’s ¡Homofobia! (Homophobia!, 2024), another favorite. Anchou is a queer, guerrilla filmmaker from Argentina, working, purposefully and intentionally, on the tiniest fraction of a Grand Tour-style budget—if any at all. The main body of the film centers around a zany, thought-provoking comedy about sexual confusion that’s shot on what seems like a very basic video camera; the framing is generally medium, the lighting non-existent, the editing minimal; dialogue scenes are mostly two-shots and the dialogue itself is dubbed, out of sync. All the while, this comedy plays out on a small portion of the screen, floating alongside at least one and often several others—including a silent film about the life of Christ—in a way not dissimilar to Masloboishchykov’s moving collage of on-screen text in …from Bulgakov. Yet, as distanced as their story is through all these techniques, the characters grow on and stay with you.

More importantly, though, there’s the frame! Which I need to explain.

So, first of all, before the screening begins, Anchou announces that it won’t be followed by a Q&A. Then the film starts, opening on a static shot of nighttime Buenos Aires, filmed, it seems, from a window or balcony. Over this shot, Anchou’s voiceover introduces the film: he’s had a “terrible” year, he says, filled with “great sadness” (presumably to do with Javier Milei and his “neoliberal death-cult,” to quote Olaf Möller’s catalog entry), but making this comedy helped him, served him like an “existential lifeline.” “I hope that it can also be transferred to you,” he continues, “in case you are also going through a period of great darkness, or worry, or anguish.” As he speaks, I note that I’ve never seen a film that addressed me so directly, so filterlessly. Even the most direct, audience-interpellating essay films generally feel like they’re talking to either themselves or their makers or an abstract Audience, but this feels like a conversation, like Anchou is talking to me. Finally, he wishes me (well, the audience) a good screening, and the sex comedy begins. When some forty minutes later it ends, having raised a lot of interesting questions, I remember the no Q&A thing and feel almost betrayed, disappointed, somehow rejected: the film had addressed me; not some abstract, ideal spectator, but me, here, sitting in this theater seat; why couldn’t we continue talking?

But then it turns out the film isn’t over, only the sex comedy part is, and I remember Anchou saying something about there being an “appearance” after the film, so don’t worry about the Q&A, ok? I don’t know what that means exactly, which makes me pretty anxious, but it turns out the appearance is just Anchou himself wearing a sort of shaman/trans-priest costume (long black robe, neon red collar, huge white feathered headdress; think Fellini’s ecclesiastical fashion show in Roma, but minimalist), standing on stage to the right of the screen and silently accompanying the remainder of the film with an array of gestures. The remainder of the film being another direct-to-viewer monologue that starts off with a kind of collective hypnosis (Anchou’s soft, repetitive VO regulating the lights in the theater and cueing some relaxing ambient sound while the white screen fades into an image of a spiral) and does so many things at once I’m now finding it kind of hard to describe: it’s a pre-written Q&A; a radical manifesto for budgetless filmmaking; a poetics of Anchou’s practice; a film-philosophical treatise on art’s existence through and in relation to limitations, which it transcends in its perpetual movement toward an always-future utopia. In it, Anchou champions explanation and recounts how he arrived at the post-film-within-the-film manifesto form: it was, initially, a reaction to a “disastrous…devastating” festival screening of his first feature film, Safo (2004), which he didn’t introduce or frame in any way and which the audience therefore rejected “categorically.” He cites historical precedents, like the manifestos of Fernando Birri. He delves in great detail into the form of the comedy we’ve just watched: the out-of-sync dialogues, for example, though apparently improvised, were anything but. “The aesthetic foundations of Homophobia!,” he explains, “are the same as that of Safo: the reconstruction of language based on production obstacles.” (!!) He says things like: “To make a film in these circumstances, when no one asks you to make it, is an act of faith, it’s an act of faith in humanity, in society, in long-term justice, in the possibility of complete happiness, and it’s an act of faith in cinema, in the possibilities for cinema to reinvent itself and to go beyond the hegemonic characteristics that seem to be eternal and immovable, and also in the possibility that cinema, even if it’s made with ball of clay, like these films are, contains the possibility, the germ of changing the world.” It’s my favorite twenty-odd minutes of the festival, and when they’re over, Anchou says: “You see? No need for a Q&A!” He’s right, of course, but I still want to prolong the conversation. So I go up to ask him for a transcript. Surely something like this must exist in print? Surely it’s already been published? It doesn’t, and it hasn’t. We should publish it here.

A few hours later, The Visual Feminist Manifesto (Farida Baqi, 2025) also presents me with a manifesto in film form, a lot of budgetless filmmaking ideas, and another festival highlight. I’m immediately—and then continuously throughout the film—struck by how perfectly the images align with the voiceover, which is lyrical, poetic, but also precise and to the point. Having always been partial to the contrapuntal, disjunctive use of sound, I’m surprised to find the affinity between the two so effective: here, more so than in any movie I can in that moment recall (nor can I now, as I write this), sound and image are in tune, synchronous, in a way that feels somehow expansive, productively accumulative, and not redundant. For example, Baqi’s words as she muses on her mother’s emotional and physical state at the moment of conceiving her—“It is inescapable to wonder: were we conceived in love and lust? Or are we daughters of guilt and disgust?”—are all the more, not the less, effective for being accompanied by shots of a movement through the universe, in which there suddenly appears the animated image of a sole woman, naked and supine, breathing in, tilting her back ever so slightly, exhaling with pleasure. The film is split into chapters, each of which elaborates on its own theme, accompanied by its own, perfectly paired, aesthetic. An excursus into fear, for example, is suddenly in black and white: the shots clinical, glacial, emulative of that societally induced self-alienation from one’s body, and its needs and pleasures, that Baqi so poignantly describes. After that, “Shame” erupts on the screen in saturated color: flushed, conspicuous, too visible, red like heat, like blood. “Shame: we gathered through intuition that the word means ‘dishonor,’ even when we did not know honor… How to explain disgrace to girls but with a word that shuts out their world, and covers it with shame?… Estranged we become from the body, we touch it with shyness, as if it were placed in our care, to clean, to purify, to keep tidy, for someone else.” Ah, to have seen this film in my teens or twenties! And again, the images reiterate, pile on, enhance—the film’s sole actress, an adolescent girl, steps into the shower, scrubbing her body pink, washing away the blood that won’t stop running down her thigh. To keep tidy, ad infinitum: the futility of the rinsing action is illustrated, manifested, physical. The reiteration feels necessary, still anything but redundant. Actually, I realize now, it’s the very notion of redundancy that the film ridicules, riles against. If every woman in the world found a thousand ways to express these same feelings and ideas, it still wouldn’t be enough.

On my last IFFR day, the indeterminacy returns. Thoughts on Peace in an Air Raid (Vyacheslav Turyanytsya, 2025) starts off like a documentary, but there’s already something off. Two construction workers stand across the road from us, discussing their lunch break and sharing recipes. It feels found, incidental, but we can hear their dialogue above the traffic noise, so they must be mic-ed up. In the next shot, a man (one of the two? It’s hard to tell) sits on some steps, eating a sandwich. Documentary footage? Probably, but—something about it (the framing? the way he avoids looking at the camera?) feels staged. There’s a few more shots like that, and then we’re inside someone’s house—seeing her walk through the door, hang up her coat, put on the kettle, until suddenly, we’re outside her window looking in, watching her roll a cigarette, while she looks out, not at us, but just past. In the distant background, throughout, a siren wails. So there’s all these little slippages, like a documentary taking a few steps documenting and then sliding, almost inadvertently, into fiction.

Except it’s not inadvertently, at all. Moments later, we’re back indoors, where the filmmaker is at his editing station, cutting one of the scenes. He talks about it with his editor. They watch it, and we watch with them—“I think it edits… right about here,” one of them says—following the film as it cuts back into the docufiction. It’s unsettling, this slippage into and out of moments that are restful, suspended, beautiful, ordinary, tinged with sadness. Precarious, like so many thoughts on peace in an air raid.

I like this slippage because it’s subtle, apparently directionless, aimless; the film just gliding along the borders of its own ontology before finally ending up so precise. Elsewhere, the slippage is both less and more obvious. In An Unfinished Film (Lou Ye, 2024)—a funny-then-sad Covid-era saga about trying to complete a ten-year-old film project—I’m certain I’m watching a documentary (vaguely wondering what prescience possessed the crew to capture such unremarkable moments as the plugging in of an old computer) until I’m certain it’s not. An Unfinished Film feels like it’s sliding, until you realize you just haven’t been watching closely enough: the information was all there in the image; it just didn’t quite click until Jiang Cheng ended up quarantined in his hotel room together with at least a cameraman and maybe also a boom operator. It’s less a mockumentary than a reenactment, but it kind of expands the definitions of both of those terms, as well as raising questions about the distinction between documentary and fiction more broadly and the usefulness of thinking cinema in those (binary) terms. In one specific moment, I wonder whether the video of an ambulance that I’m seeing Cheng watch on his phone was something someone really shot in early 2020 or whether it was recreated for the film, and then I wonder why I’m wondering that, and what difference it would even make—in the context of a film that blends documentary premise & fictional technique for the precise purpose of telling an apparently neverending story about a movie that was already slipping in and out of its makers’ lives when Covid made a mockery of the whole thing; made it so the cast and crew’s reality was not just filtered through and beholden to the videos on their screens, but embedded there entirely.

In Tragédia (Bernardo Zanotta, 2025), I’m confronted with what I’m pretty sure is the exact opposite: a batch of documentary footage that’s fictionalized by being treated as documentary footage that shows other, or more, than what it shows. Over innocuous, even boring, scenes of a family vacation shot in the early 2000s (when the filmmaker was thirteen), Zanotta recounts an improbable tale of deception, jealousy, conspiracy to commit murder, parricide. It’s nothing new, but it’s fun, and he does have a way of using the discrepancy between the footage and story, or the surplus it generates, to make you wonder still interesting things about not just this tale, but the medium that’s used to tell it. Is it just the murder that’s invented or is it the whole thing? Who is this woman on the screen, and what is her relationship to the filmmaker? What else is happening that we can’t see? What would we learn if the frame were just a little bit wider, if the camera tilted a little lower, panned a little further to the left? What’s happening behind the camera? Who shot the footage and what was it meant to mean to them? Do they remember? Does it matter? It’s as though the friction between the on-screen material and the off-screen inventions about it opened up a third space, vague and half-formed, that doesn’t offer any answers about the relationship between the two but, on the contrary, just serves to raise more questions. The film spilling outside its borders, outside itself, into a realm of endless possibility.

I also liked (in chronological order of viewing):

Someone Else’s Children (Tengiz Abuladze, 1958). A kind of Georgian Mamma Roma, if Pasolini was light-hearted, fundamentally optimistic and interested in the hopes and dreams of young (pre-adolescent) children. Papà Tbilisi. Delightful from beginning to end. And the moustache on Asmat Qandaurashvili! Revolutionary.

Monólogo Colectivo (Collective Monologue, Jessica Sarah Rinland, 2024). Observational documentary about a small “network”—in the director’s own words—of zoos and animal sanctuaries in the Buenos Aires area. The animals sometimes move from one facility to another, and sometimes back again. Everyone involved cares for and about them. We see feeding sessions, overhear worried phone conversations, attend animal-training workshops. I’m not sure this was actually Rinland’s intention, but by the end, her film’s thoroughly conveyed the absurdity of a society that works as hard at keeping animals on captive display as it does at rehabilitating them and returning them to the wild. Similar dynamics are at work in Rinland’s Katoenhuis installation Extramission: The Capture of Glowing Eyes (2024), which brings together Stealthcam footage of nutrias recently relocated from Europe to their native Argentinian habitat, thermal imaging video of taxidermists at work at London’s Natural History Museum, and spreads from old issues of National Geographic showcasing the pioneering work of wildlife photographer George Shiras 3rd, who invented the camera trap as an alternative to hunting.

Vielleicht bin ich wirklich eine Zauberin—Filmregisseurin Mai Zetterling und ihre Filme (Katja Raganelli, 1989). Perfectly made TV documentary about the pioneering work of Swedish actress-turned-director Mai Zetterling, screened alongside Zetterling’s own The War Game (1965). Part of the Katja Raganelli focus section that I wish I’d been able to see in its entirety. Raganelli’s other docs included here were on Valie Export, Delphine Seyrig, Lotte Reiniger, Margery Wilson, Alice Guy, Márta Mészáros, Agnès Varda, and Annot & Rabe Perplexum. I mean!!

Primitive Diversity (Alexander Kluge, 2025). A kind of wordless experimental essay on AI and early cinema, that I liked the idea of and intro to more than the film itself. I wanna be playing around with new technology in my nineties and filming festival intros about it where I quote Miriam Hansen and declare that contemporary cinema is like a phoenix, reborn from the ashes! The film, though, felt kind of like a sketchbook of early ideas, with scope for development.

Revival Roadshow (Luke Conroy and Anne Ferhes, 2025). If IFFR 2025 is anything to go by, VR technology still has a ways to go (from the ill-fitting headsets that let reality into your peripheral vision, to the 3D images themselves, whose perception-altering novelty, in my limited experience, wears off in about a minute), but I did enjoy watching Revival Roadshow, a dystopian pop-baroque kitchen sink of everything that’s laughably, tragically wrong with our society. The core narrative is a conversation between a girl trying to sell a painting of her illustrious ancestor Abel Tasman, the 17th century Dutch explorer, and the art dealer she’s trying to sell it through. But it keeps getting interrupted by ads. “Upload your grandma to the cloud!” one urges; “Litter your way to luxury!” goes another. Around the girl and the dealer, a (sometimes literal) sea of colonialist and Western capitalist debris includes classical-style portraits of not just the usual suspects (Zuckerberg, Musk, Trump) but also the likes of Gordon Ramsay, Woody Allen, Russell Brand, Tom Cruise.

Blazing Fists (Takashi Miike, 2025). I need to write a book on Takashi Miike, just to try to understand what makes his many, many films so perfect. Is it the comic timing of the cuts? The joyful exuberance of the sets and costumes? The countless impeccably cast extras? He’s sixty-four, on his thousandth movie (120+, Patrick Frater says in his introduction to the Big Talk with Miike, but who’s counting anymore), and still every one of his frames continues to burst with dozens of realized and germinating ideas. Plus this one’s about adolescent dreams, overcoming adversity, believing in yourself when no one else will. “If you have a dream and you work hard,” he says in Q&A, “sometimes a miracle happens.” Two hours of heaven.

Die Ermittlung (The Investigation, R.P. Kahl, 2024). Uncompromisingly faithful, four-hour adaptation of Peter Weiss’s classic 1965 play, which is a kind of minimally altered condensation of the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials of 1963-65. As difficult to watch as you’d expect such a thing to be. Hard to say what’s more nauseating: the survivors’ eyewitness testimonies, or the defendants’ denials of responsibility—both increasingly outrageous, preposterous, unthinkable. Both equally true. Most disturbingly, perhaps, I’m the youngest person at the screening, which is far from sold out.

Videoheaven (Alex Ross Perry, 2025). Three-hour video essay about the history of the representation of video rental stores in Western (mostly US) film & TV, adapted from an unpublished chapter of Daniel Herbert’s book Videoland: Movie Culture at the American Video Store (UC Press, 2014). I never realized how instantly vilified video stores were in the early 80s, when they started popping up all over suburbia to rent R-rated horror films to kids! Unapologetically nerdy, nostalgic, fun-fact filled fun.

Happy Holidays (Scandar Copti, 2024). Expertly written dramedy about a well-to-do Palestinian family from Haifa (Copti’s own hometown), built around the three siblings’ romantic entanglements over one long holiday season. The brother, for example, was dating an Israeli woman before she became pregnant with his child and the whole thing got a little complicated. The tensions both among the Palestinians (of different generations and mindsets) and between the Palestinians and their Israeli neighbors are very real, occasionally shocking, but also kind of understated. Today, it feels both like a vitally different perspective on Palestinian reality—a far more privileged reality than the one we’ve been seeing on our phone screens this past year and a half—and oddly detached from current events. That the film was obviously written before October 7 doesn’t quite iron out the fact that it exists in and speaks to a bubble in which being Palestinian in Israel is bad, but not unthinkably horrific. A bubble that I’m not suggesting Copti should either burst or distance himself from—on the contrary, I deeply appreciated the film’s embeddedness in his own underrepresented reality—but that does feel reflective of the broader (global) obliviousness to the conditions in Gaza and the West Bank prior to the recent explosion of Israeli violence.

Baby Blue Benzo (Sara Cwynar, 2024). Too-cool artist’s essay film about capitalism, images, Pamela Anderson, and the most expensive car ever sold (spoiler: it’s the Mercedes Benz 300 SLR). The voiceover narration quotes from philosophers and meme-makers (“sure, the planet got destroyed, but for one beautiful moment we made a lot of money for shareholders”) and asks things like “If I have an image of the car, is that just as good?” I mostly liked the mobile-collage technique that it took me about seven of the film’s twenty-two minutes to figure out: it’s layers of large sheets of glass, that are sometimes still, sometimes moving, so that when the camera tracks alongside them, or dollies backward or forward, it looks like the images stuck on top have been digitally collaged in wonderfully complex ways. Ingenious. Combined with the myriad actual edits, split screens, digital pans and zooms, etc., it’s all very visually impressive, and also very fun to watch.

Flowering and Fading (Andro Eradze, 2024). Probably my favorite short of the festival, and maybe my favorite short in a really, really long time. I feel a little guilty about how much I liked it, because it doesn’t do much other than create oneiric atmospheres and make you wonder how he got all those objects to float in mid-air like that and whether it was very expensive? But the shadows creeping over the forest floor, the dog sighing in his sleep, in the night, the soundless house, the moonlit curtains, the unseen nightmares in the sleeper’s mind, the world, living, without us—it’s all, as Rebecca De Pas writes in the festival catalog, “an ocean of absolute beauty.”