Homecoming

A conversation with Jacopo Benassi

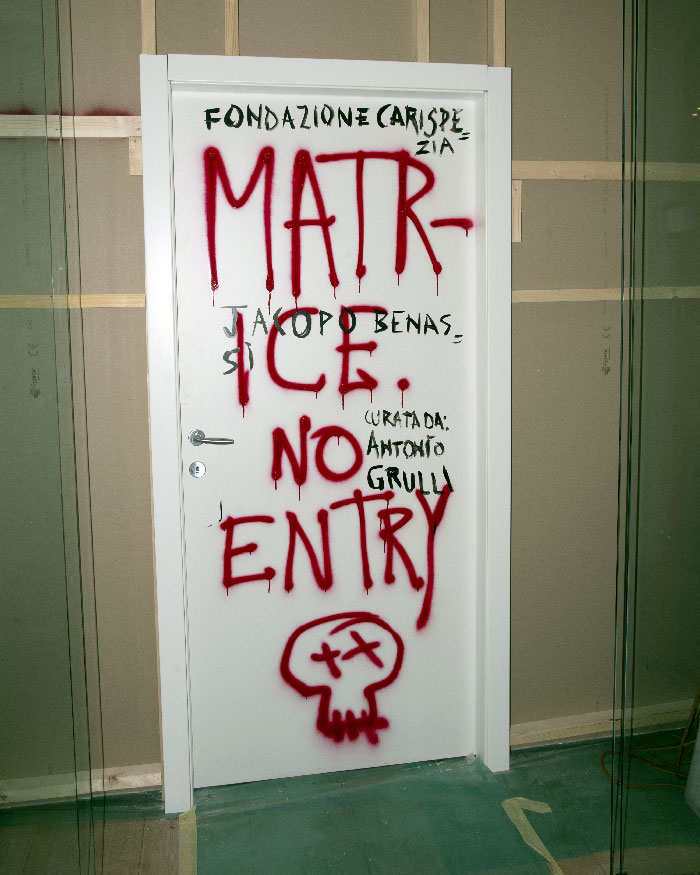

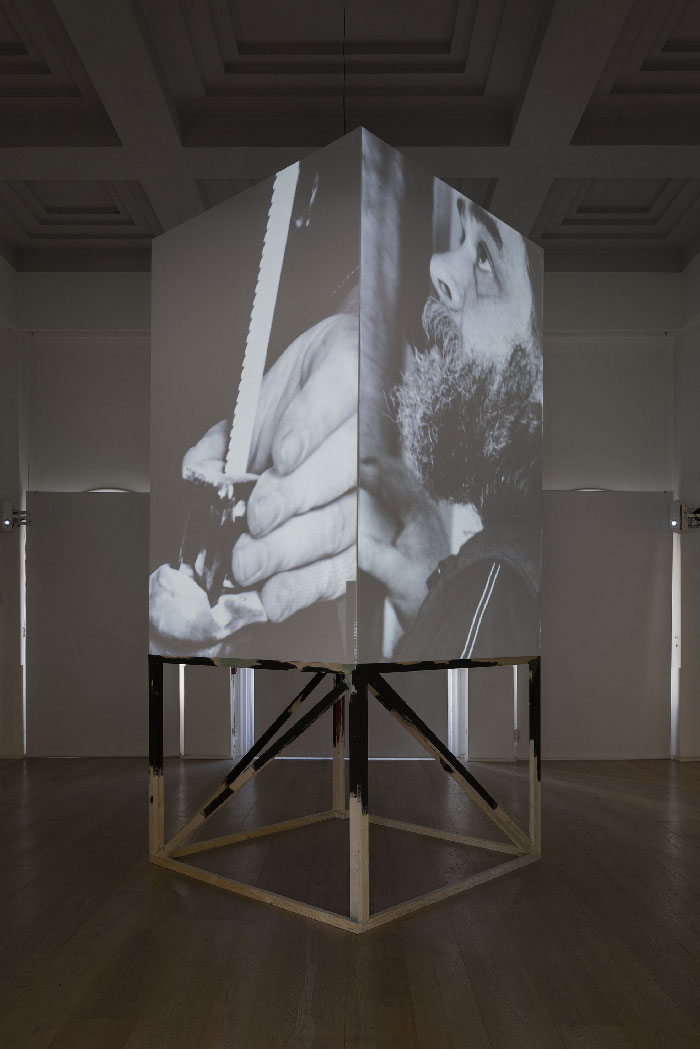

Curated by Antonio Grulli, MATRICE is an exhibition by Jacopo Benassi at Fondazione Carispezia, the homecoming of the artist, after years of wanderings (and recognition) in Italy and abroad.

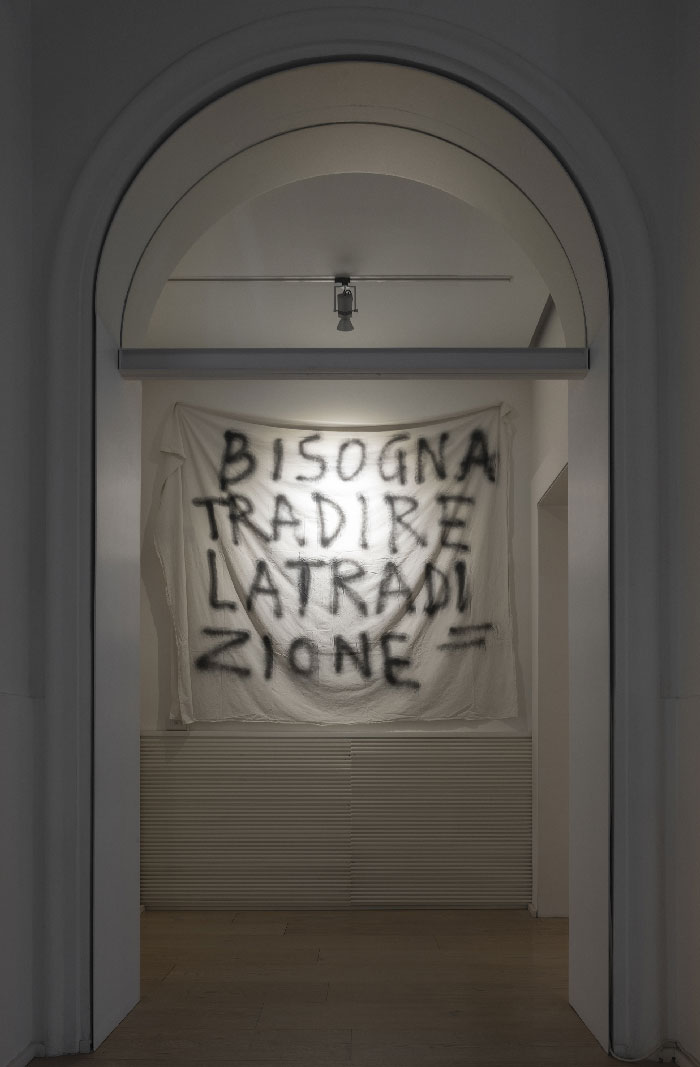

Antonio Grulli: Jacopo, a lot was written about your work as a photographer, performer, and artist, and you also had the chance to tell about it on several occasions. So now I would like to talk about your cultural—or counter-cultural—background, basically the environment in which you were educated both as a man and an artist. You often mention your youth experiences, but just briefly. I would like to take this opportunity to discuss them with you thoroughly. Let’s start from the punk scene you belonged to, both in La Spezia and in other places in Italy and abroad: I think it is the very first step to understand the most important imprint you had, as well as the idea of art which better represents your personality. Like the punk movement, you love contemporaneity in a fiercer way, but your heart is also desperately romantic because you believe that talent is not only possible, but also necessary. You refuse to make art as a job, and still conceive it more as a vocation, or a hobby. What you love is an art devoid of commercial and power-related strategies, and your work is based on an unsteady elusiveness which lives by instinct and by a never-ending process. DIY will always remain your main approach. All combined with the occupation of abandoned sites, which happened a lot during your youth.

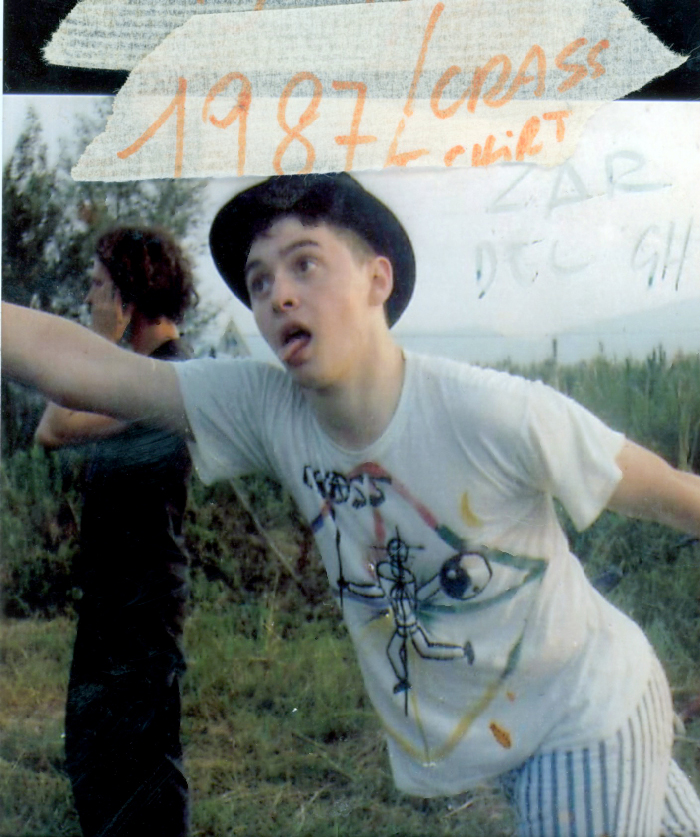

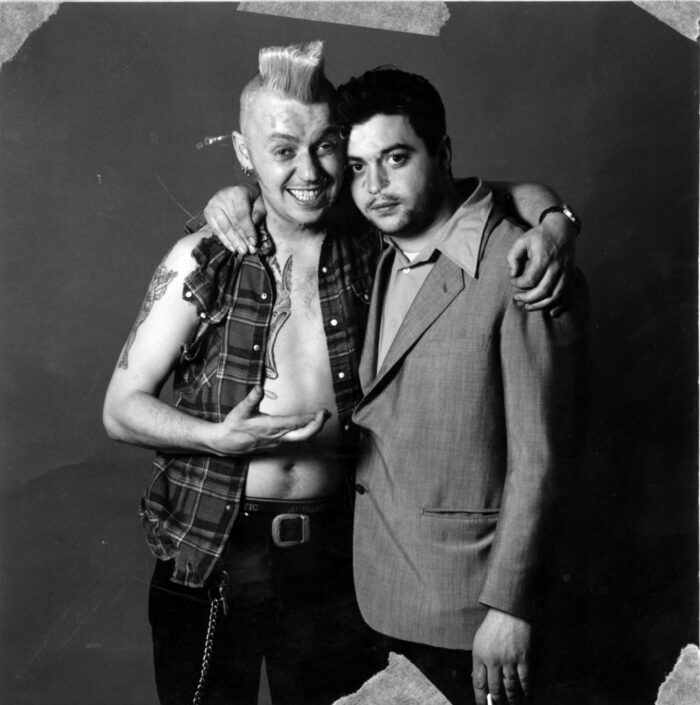

Jacopo Benassi: I remember that, as a child, in the 80s, I had an ardent admiration for punk. It was around 1982 and 1983, or maybe 1984. My dream was to become a punk. Maybe at that time I began to feel different, more than different actually, since I already had a great doubt, indeed certainty, of my homosexuality. I believe this was the real reason why I liked punk culture so much. I saw it as an environment where everything is based on the concept of diversity. One day, after a concert of Nico of the Velvet Underground band at Superficie, a wonderful pub in Camaiore, Tuscany, which later changed its name to Kama Kama, I met Renzo Davedi, aka Benzo. He was the singer of Fall Out, one of the first punk bands in Italy. He was the hero of my teenage years (I was 17 at that time). Benzo invited me to several meetings every Wednesday at his house, and when I went there, I was happy and afraid at the same time. Professor Bad Trip (the artist and illustrator Gianluca Lerici) and Benzo’s girlfriend, Anna Vespa, were there too. We spoke about the magazine Adanà, an anarchist-oriented punk fanzine. This first step influenced me in depth. I remember that Benzo encouraged me to make art. I worked as a mechanic back then, but he told me I could be an artist. Thanks to his words, I began to draw skulls… it was funny. But perhaps my first real work was a grease-stained hand with a wrench stamped on a paper sheet, almost like a stamp. In that period, other people and I occupied a former school in Vignale (a hamlet near La Spezia) which later became the community centre CSA Kronstadt, the starting point of my career. I was born in there, my second matrix, among political flyers and posters of punk bands. A lot of people from the Italian punk scene of the ‘80s passed through there with their independent productions. The first exhibition I did was Arterie barbare at CSA Kronstadt. It was a group show where I exhibited a painting with a deposition of Christ, the same work we exhibited at Fondazione Carispezia. It was a Christ pierced by forks; I thought I was doing something blasphemous but now I realize that maybe it was not so blasphemous at all.

How and when photography becomes part of the story?

In that period, I bought a camera. I started opening the camera and burning the roll—my very first roll. And soon after I attended a photography course with Sergio Fregoso, a photographer who was born and raised in La Spezia, and intentionally stayed there for all his life. He taught me to look in and out of the camera to build a photo. From this moment, I had an artistic path to follow. After making a darkroom at CSA Kronstadt, I began to print my first developed shots. They were mostly photos of punk bands. At Kronstadt I also did my first exhibition as a photographer: a group exhibition called Daguerre Daguerre for the 150th anniversary of Louis Daguerre’s death. Sergio and Sara Fregoso helped me mount it. I invited the local photographers of La Spezia, people I admired at the time. I dreamed of having a similar career.

In some ways, this can be considered your real school, can’t it?

Yes, it can. I am not that kind of person who used to spend years learning from books. Of course, I read several things published by independent newspapers or by Nautilus. I used to read poetry. I still have all the books I bought back then. I have been buying photography and art books since the 80s.

In those years, you also took part in the Mail Art Movement—an almost-forgotten phenomenon today, yet crucial to grasp your art. In the Mail Art there is a Fluxus, Dada, and Punk spirit associated with cooperation and energy exchange among artists within a specific community: something fundamental in your world and Art vision.

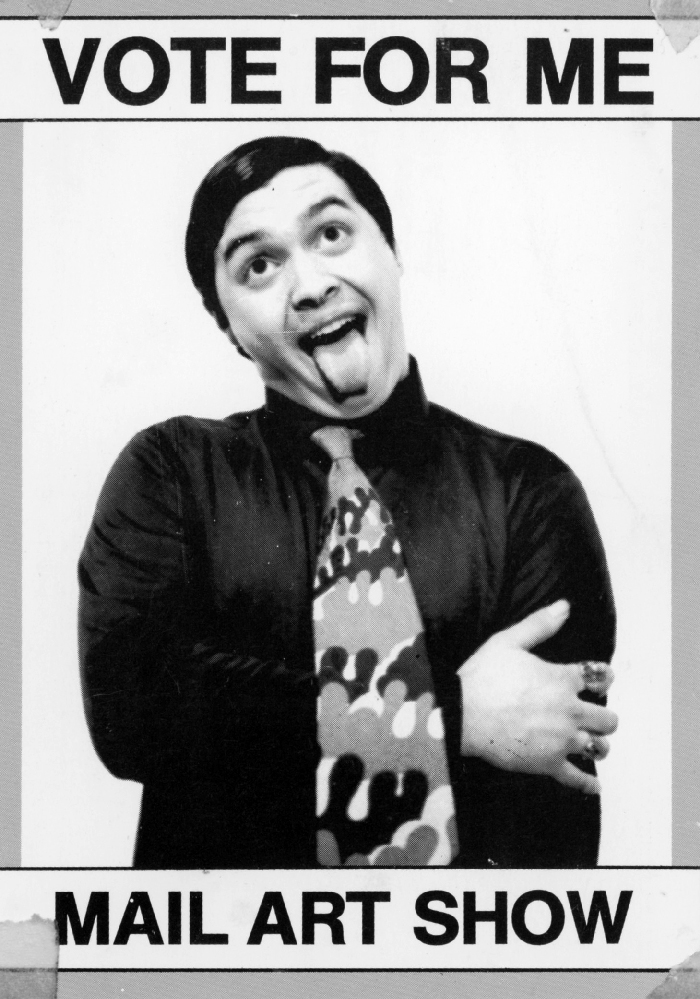

Yes, absolutely. Kronstadt was set on fire by a group of fascists—silly people who wanted to create disorder and almost lost their life for it. So, with Bad Trip, Renzo Daveti, and Anna Vespa I opened the cultural association Katodik Karma inside an ex art gallery donated by a crazy man from La Spezia. In this space we organized some Mail Art events with Vittore Baroni, one of the main representatives of this artistic movement. Mail Art and artists like Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, Ray Jonson, Shozo Shimamoto were essential for me. They all are artists that I met or that I got in touch through Mail, and they molded me a lot. In 1989 I made my first mail artwork, the invitation “Vote for me”, a self-portrait asking people and artists to vote for me. In 1990 I went to London where I made the invitation “Bad Dog for Bad Child”. Many others followed, and I was the main character of most of them. It was the first time I had traveled around the world! Thanks to Mail Art I could go around the world and feel part of a community, even though I stayed in this city. In the 90s we also organized an exhibition about Vittore Baroni and a video review with Sandra Lischi about Mr. and Mrs. Vasulka, Bill Viola, Nam June Paik. At that same time, the first Hi8 video cameras came out: they were very cheap, affordably priced. I took a bank loan with my employer to buy one and started making videos. But since it was part of my education, I started with conceptual videos: everything was blurred, I never looked at the camera, but it was like doing a film… Even in the video I adopted the same punk-origin approach we were talking about earlier.

In those years, you also were into politics.

I did a lot in politics, also with small actions: they were not relevant but they made me feel like an activist, a person “against” something. We didn’t know why we were “against”, but we actually were against something. And we never asked for anything… Once Sergio Fregoso told me: “try and ask before being against something.” This sentence made me think a lot. We organised events focused on vivisection, absurd exhibitions about animal torture, video on the English Liberation Front, we often went to Cador, a cinema run by priests, to watch the first movies by Almodovar, Kieslowski, Genet, and many other things you normally did not watch in cinemas. Back then, we also organized a collective photo exhibition curated by Sergio Fregoso himself, who was president of Arci in that period. It was inside an occupied place called Casermette. Together with me, many other photographers exhibited their photos: Cristinano Guerri, who now is the talented graphic director of Feltrinelli, and Francesco Ercolini. We also managed to print a catalog—it was a small yet very serious exhibition. We handle our pictures on steel cables, I think I still have the records of it… A friend of ours, Petra A. Wende who studied in Carrara at that time, took part in it too with a video about the 80’s Berlin scene. Then we all got arrested and taken to the central police station, and the exhibition was closed. But we actually won the legal case against the Navy over the occupation and the claiming of abandoned places. I think it was the very first time that someone won a case against the Navy in Italy, none of us was condemned.

In those years, the community centre “Skaletta” was created. It is a legendary place in La Spezia, still active today.

Skaletta was created right after those events. It was a legal revival, although we didn’t lack for mistakes and pickles. We founded it with ARCI (Italian Cultural and Creative Association), and I was the president of it. It was amazing, there was a leading, intergenerational vibe with young and old people… During the first period of Skaletta, I made Teste (“Heads”), a printed poster with 140 faces that showed the interweaving of generations of that place. I hung the poster all over the city of La Spezia—it was a very huge work because back then we still needed to scan the negatives. Unfortunately, I don’t think I have anything left about “Teste”. It’s a pity, I’d really like you to see it: it was a poster depicting 140 faces with the word “Teste” at the center. It was my first project related to Skaletta. It was a very important period for me: until 1995, I still was a quite hesitant photographer… I took pictures with flash, without flash, I followed different styles, I was very influenced by many of them. I took some pictures without flash for the cover of Fall Out’s record at the fascist slaughterhouses of La Spezia—a very beautiful place before it was destroyed. I was still working with the punk scene back then.

And when did you find yourself?

Right at that time, when I confessed my homosexuality; up to that moment, I thought I would have never told anyone about it. When I did it in 1996, everything became clear to me. Right at that time I found my own light, the light of my photos, my own style.

When does Portrait date back to?

It dates back to 2000, when I opened my first club, the Portrait. I wanted a place where to organize photographic exhibitions. The first seat was in Rebocco, a hamlet near La Spezia, then we moved to the city center. In 2005/2006 I moved to Milan and I met Federico Pepe, who supported me in another project focused on publishing, magazines, advertising, exhibitions and books. He also asked me to take part in the first issue of Le Dictateur.

And when did you move back to La Spezia?

In 2011. I ran away from Milan and I decided to open the Btomic club, in La Spezia. Milan was changing me too much, magazines were changing me too, I was forced to buy beautiful lenses, way too cool and elegant, too professional. I got scared, I was changing my world-view, so I ran away, well aware that I could have earned a lot of money if only I had been a bit smarter. Then I called my best friends (Lorenzo D’Anteo, Gianluca Petriccione and Roberto Buratta) and we opened the Btomic club. I wanted to bring everything I had left in Milan and all I had done in my punk period to Btomic, this time with a stronger consciousness. In 2011 it was like I started from the beginning again, from Kronstadt, printing fanzines again (with a photocopier I had bought) and organizing small festivals again. In the meantime, I documented everything that happened at Btomic: I recorded live shows, I took pictures, I ran interviews; all made with love, I’d say. I met a lot of people that came across Btomic, and with a lot of them I still work today.

I remember that time very well. We met and started to work together in those years. I think Btomic played a great role in your artistic growth. It was a bar, a restaurant, a place with live music and events, but most of all it was a place entirely curated by you. It was also a photographic trap, an artistic studio disguised as a club where you invited your preys and took pictures of them. It seems you began to be attracted by performances right at that moment, that’s when you started with it.

When I closed Btomic, I felt the urge of performing and being on the stage, so I asked Kinkaleri to help me understand if I were able to do it. We organized various meetings, I stayed with them and then we ended up with a final show. From that moment on, I started to perform. However, thanks to this experience, I understood that the camera is something fundamental in my artistic path, also when I perform or I paint, when I make sounds or sculptures—she has to be there, she is fundamental and thanks to her I can also read the other artistic languages I take possession of. In this way I also managed to go beyond photography, to “disturb” the world of photography, because I stated myself with it. In this very moment I became fully aware of being less a photographer and more an artist. It’s like I didn’t know how to define myself—I am a photographer for sure, someone who knows photography, and then, perhaps, I’m an artist. That’s how I feel.