Hee, haw, whoop

Viral Occurrences between Publishing “and” Performance in the Work of Antonia Baehr

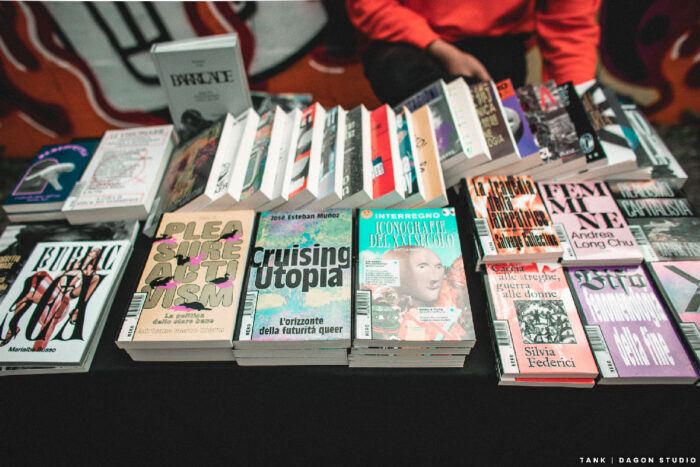

On Sunday, October 1st, from 2PM to 2AM, the queer independent publishing festival FEIQ hosts a selection of independent publishers and artists operating in the fields of arts, design, visual culture, and the dissemination of new epistemologies at Tank – Serbatoio culturale in Bologna. In dialogue with the fair, for its second edition the public programme takes a different direction, focusing on performative practices and how body languages emerge in independent publishing, from festival catalogs to artists’ books. Through the involvement of publishing houses, artists, scholars and a pluralistic curatorship, FEIQ renews Tank’s collaborative and community-oriented approach, through a reflection that bridges publishing and performance.

What I would like to propose, while awaiting the festival’s programming to kick off, is to dwell on the “and” between publishing and performance, on that in-between space to ponder what lies there. The underlying reflection behind the festival on the hybridizations between the two disciplines is a valid assumption; lecture-performance, books-choreographies, talks, collective readings have, in the past twenty years, occupied a position that is hard to overlook in the contemporary art scene and performance festivals, further expanding and articulating, through the tenets of performative practices, the versatility and presence of the book in the broader field of the arts. However, in response to the invitation for hybridization put forth by artists through their works and practices, and by scholars through theoretical contributions, I would like to reflect on that “and” which simultaneously unites and divides, seeking to maintain its integrity, undoubtedly blurring its boundaries but without completely nullifying them. On the one hand, there are books, preferably printed and bound, and on the other, there is performance, an unrepeatable staging that involves the co-presence of performers’ and spectators’ bodies within the same space and time. What happens when these two practices engage in dialogue but, at least formally, remain within their own disciplinary boundaries? What happens when, despite sharing the same name, they do not meet halfway?

The presence of printed matter in contemporary performative practices is part of the historical, social, and cultural context that has led to a veritable explosion in publishing and all forms of knowledge expression drawn from academic, journalistic, and political realms into the artistic disciplines. In the 20th and 21st centuries, publishing has become a site of experimentation and community-building, capable of meeting the needs of an ever-growing number of authors; self-publishers, visual artists, performers, choreographers, fashion designers have turned to publishing objects from diverse aesthetics and perspectives. The book—a Zelig-like entity devoted to nomadism—has transformed into a zine, a manifesto, a billboard, a phrase on gallery walls, a t-shirt, and alongside performance, it has become a score, a conference, a lecture.

I would like to shift the focus to the more traditional form of the book, which, despite the broadening of the concept of expanded publishing, remains a constant element in contemporary artistic production. The centrality assumed by the written page since the second half of the 20th century is symptomatic of the search for a space, often free from constraints and censorship, to accommodate programmatic assumptions, intentions, aesthetics, imaginaries, and simultaneously, the blurring of boundaries that separate works from theoretical analyses. Artists took the floor, incorporating the material and expressive form of discourse into practices and works; they have blurred the boundaries between the work and the research process, between the work and its interpretation.

The self-signification of the book, which requires no other forms of understanding than that conveyed through reading, has shifted the aesthetic experience into the realm of discursiveness, tilting the spectator’s position with an invitation to actively participate in the process. However, to understand that “and” between publishing and performance, it is necessary to narrow the prospective, or at least deflect it. Not only because the use of the book is more easily understandable for conceptual works, which make critical inquiry and language an artistic activity in itself, than for practices that employ the body and gesture as ephemeral matter, but also by virtue of its versatility, which allows it to embrace extremely diversified aesthetic and political demands.

What can be considered one of the most enduring statements of the performance studies immediately dampens the enthusiasm of the encounter between the book and performance, which inspired the second edition of FEIQ.

“The only life of performance is in the present. Performance cannot be saved, recorded, documented or otherwise participate in the circulation of representations of representations: once it does, it becomes something other than performance. To the extent that performance attempts to enter the economy of reproduction betrays and diminishes the promise of its own ontology. Performative being, like the ontology of subjectivity proposed here, is done by disappearance. […] The document of a performance then is only a spur to memory, an encouragement of memory to become present.”

In the essay The Ontology of Performance: Representation without Reproduction (1993), the theorist Peggy Phelan declares the life in the present of performance, claiming the condition of transience and the escape from archival forms as potential epistemological and political tools. Disappearance is the tool of resistance to reproduction, reification, and commodification imposed by the art market. Phelan urges us to refrain from the desire to record, document, and preserve through devices that not only would insert performance into the “circulation of representations of representations” imposed by capitalism but would also atrophy it in the inability to retain the surplus associated with the bodies that define it.

“The desire to preserve and represent the performance event is a desire we should resist. For what one otherwise preserves is an Illustrated corpse, a pop-up anatomical drawing that stands in for the thing that one most wants to save, the embodied performance.”

Phelan’s critique is directed not so much at the means of documentation per se, for which she does not deny the creative value, but rather at their improper use. Nevertheless, it is possible to discern a value system triggered by the ontology of performance in favor of direct experience, in relation to which the documentation would be twice removed. It’s a strange return of shadows on the cave walls, widely criticized by a series of authors, including scholar Amelia Jones, who, in a 1997 issue of Art Journal, asserts the hermeneutic validity of the delayed experiences of spectators engaging with a performance through documentations. Setting aside Phelan’s postulate and the debate it sparked, I would like to attempt to shift the reflection, returning to that “and”, to test, in a sort of reductio ad absurdum demonstration, the validity of such a clear-cut separation and hierarchical structuring between publishing and performance.

Rire, Laugh, Lachen is a 112-pages printed publication realized by the Berlin choreographer Antonia Baehr in October 2008, published by L’œil d’or, an independent publisher founded in Paris in 1999, and Les Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers, a center for the development and production of performance and choreography in Aubervilliers. The dark green cover immediately reveals the purpose of the book; the author invites the reader to laugh—three times, in three different languages, with a bold font— providing the book as support for the action. The tools, to be brought to life through practice, are divided into Exercices pour le rire (or Laughing Exercises) and Partitions de rire (or Scores for Laughter). The former are intended for group practice, the latter for solo performance, but, as Baehr states, “everything remains possible.” The exercises gather notations proposed by the laughter instructors Barbara Manzetti and Claude Bokhobza from the first workshop held in Aubervilliers as well as notations drawn from the practice of laughter yoga by Chantal and Bakary Diakhité. The scores are the fifteen tools designed by a group of friends and acquaintances—visual artists, musicians, dancers and family members [1]—as “birthday gifts” for the choreographer. Designed to be performed individually with durations ranging from 5 to 15 minutes, the Partitions de rire deal with the action of laughter, not with being funny. The result is a varied constellation of contributions. Christian Kesten, addressing anton-töni-a, proposes a three-act movement, providing details on time, rhythm, and laughter tone through description and notation. The first act is intended for Antonia Baehr; the second act is for a group including Antonia Baehr, Henri Fleur, Werner Hirsch, Henry Wilt, Antonio Capra, Henri Antoine de la Rigolomanie, Anton, and Töni; the third act, a laughter version of Queen’s Don’t Stop Me Now, is for Henri Fleur. Over the span of two double pages, William Wheeler and Nicole Dembélé organize a staff notation score for a duet for theremin [2] and laughing voice, concluding with two photos, one of Nicole laughing and the other of William playing the instrument. Henry Wilt’s contribution is a handwritten text distributed within a grid of four columns and ten rows. From left to right, the columns specify the rhythm of the “HA”, the list of actions to be performed in English, the French translation, and the total duration of each group of actions. Manuel Coursin creates a score that associates the sound of laughter with the sound produced by different types of balls. Eleven actions juxtaposed with stills from a video are contributed by Naïma Akkar and Baehr herself. With Valérie Castan, the choreographer offers the reader Un après-Midi, Variation for Laughter, a piece composed of four phrases described through photos, a laughter patter utilizing facial muscles, and two alternating silent laughter phrases. With Sylvie Garot, Baehr designs “The Magnifying Glass”, calling on the performer to interact with a suspended glass object. This intervention spans on a double page; on the left, a double column in French and English accompanies illustrations of the score’s phrases, while on the right, a grid sheet translates the Berlin midnight New Year’s Eve laughter of 2007 by the father into a score. Bettina von Arnim, the choreographer’s mother, with imposing and chaotic handwriting, questions whether a laughter devoid of cause can induce laughter. Upon her daughter’s confirmation, she responds with a notation piece where notes intertwine with faces and smiles reminiscent of the Cheshire cat. Ulrich Baehr contemplates the genetic similarities in smiles, offering a score that allows one to inhabit the smiles of others. With “Laughter Score for Werner Hirsch”, Frédéric Gies instructs the performer to execute eight types of laughter originating from the stomach, kidneys, bladder, liver, lungs, intestines, gonads, and brain, interspersing each description with illustrations highlighting the involved body part. Steffi Weissman’s contribution is a composition in three parts—“me”, “bird”, “joy”—to be performed individually or in sequence, each accompanied by a descriptive text in German, two drawings, and a list of thirty actions. Andrea Neumann invites the reader to briefly focus on the face of each spectator, from left to right, row by row, choose one and use it as a trigger for laughter. Isabell Spengler translates onto two double pages the content of a recording to execute a proper causeless laugh on stage. William Wheeler and Stefan Pente close the sequence with a score that involves using a wig as a sensual laughter catalyst, providing dramaturgical descriptions and photographs for the creation of six different hairstyles.

Rire, Laugh, Lachen is a publication on the mechanics of laughter, its physiological components, the qualities of a gesture devoid of causes and effects, laughter as a manifestation of sound and the body, or as a process of immersion in the other. Above all, it is a portrait of Antonia Baehr, encompassing all her re-appropriations, traced through the affective relationships that drive each contribution. The reader is not only invited to use the book as a tool for performing, but is also called to wander among bodies, primarily that of the choreographer, but also those of her mother, father, friends, and acquaintances. Antonia Baehr asks not to be surprised by the various names to which the scores are addressed; her body is a boundary point, “beneath the make up there’s just more make-up,” beyond the masculine and the feminine, offering itself to the game of mirrors: Werner Hirsch, the non-dancer with a mustache; Henry Fleur, the dandy non-musician; the choreographer Antonia Baehr; Ida Wilde’s husband; Töni, the girl with long hair; the drag queen Agnes B. Rire, Laugh, Lachen is a tool for wandering through acts of mimicry, thefts, and appropriations, adopting what the author herself defines as “a certain feminine laughing performativity.” The gestures, directed towards the choreographer first and us as spectators later, wander, possess the bodies in their path, without belonging to us.

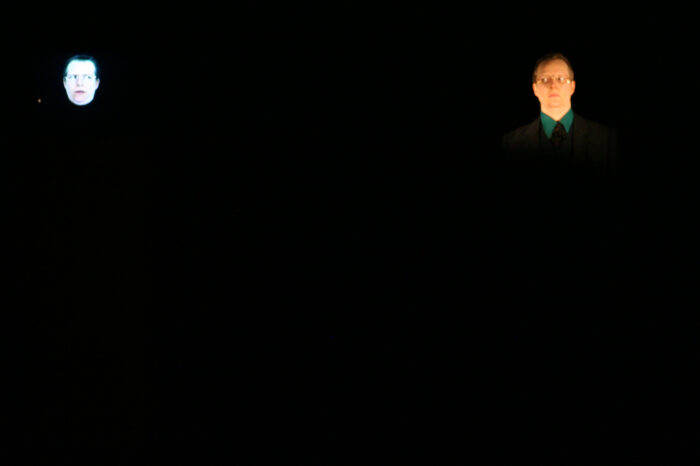

Rire, Laugh, Lachen is also a gateway to another dimension of space and time; Lindy Annis’s ekphrasis [3] is a rabbit hole leading to the performance Laugh. It’s a pleasant evening in April, the premiere of the work, during which a group of about a hundred people gathers at the Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers in an industrial building with red bricks. There’s a sense of anticipation. A bell rings, the audience enters, sits down, the doors close, the lights go out. Antonia Baehr enters in a dark blue three-piece wool suit, pinstriped. A black silk scarf with a pin featuring Joan of Arc’s image peeks out from her green shirt. Brown leather lace-up shoes; short hair combed backward. Facing the audience, she explains the compositional structure of the performance, lots of scores, lots of people, a birthday. On a black fabric suspended at the back of the stage, a projection reveals a name, Kesten is the author of the first score. Baehr reads it, then sits in a black chair in front of a lectern in the center of the stage. The sound “he-he” immediately creates an affective atmosphere. Then the room remains empty, she exits. This is a sharing of scores, not a theatrical display of pathos. Kesten’s second movement, a constellation of different forms of laughter, takes over. It is replaced by the theremin composition, derived from Nicole Dembélé’s laughter, one of the participants in the early workshops. Hee, haw, whoop. The choreographer decides to inhabit Nicole’s recorded laughter with a perfect lipsync, then duet with her. In Henry Wilde’s score, a sequence of triangles drawn with the right hand is punctuated by the rhythmic and constant appearance of the sound “ha” at one of the sides. Then the escalation of “ha” generates laughter and involuntary coughing. In Manuel Coursin’s composition, Baehr moves a black bag from the side to the center of the stage, opens it, takes out a yellow ball, throws it against the floor, then more balls, alone or in pairs, the throws interspersed with pauses to reflect on expectations. Then she moves away from the audience to shift the focus from the face to the body, inhabits the movements of Naima Akkar’s video-recorded laughter, which, like nachleben, cyclically resurface on the skin. Her breath opens up to Valerie Castan’s composition. Baehr assumes the postures of the laughter of several people, who appear in photographs. She laughs, touches her stomach, bends, contorts. From above descends the rectangular magnifying glass of the light designer Sylvie Garot, the interpreter’s face distorts, her voice becomes superhuman, a demon. Intermission with water and wine, genuine laughter from Nicole Dembélé. Second part. The stage is an academic setting: a television, a table, a sound system, three chairs, a blackboard on the right wall, a metal stick. Baehr reenters and declares that the scores belong to her parents. A recording takes the audience into a conversation with Bettina von Arnim, her mother, who shakes the foundations of the project: laughter cannot be commanded, and laughter without cause is not contagious. The father’s score manifests itself in the vinyl audio recording of the laughter of the Baehr family members. A search for genetic connection. Antonia is now a DJ navigating through samples. With Frédéric Gies, laughter is connected to multiple parts of the body. The audience is called to participate: which parts of the body among those proposed? The decision is the trigger for laughter. Darkness. The sound of lace-up shoes. A monitor lights up. Baehr’s head without context, like laughter. She wears glasses, hair pulled back. 15 minutes of laughter. A light illuminates the head, this time attached to the shoulders of the choreographer in the center of the stage. She starts laughing, moves, almost falls onto the audience, the video-head corrects her, she doesn’t perform the laughter well, then stops. [4]

The “and” between Rire, Laugh, Lachen and Laugh, between publication and performance, is a viscous space of slippage. The publication leads to the performance, and the performance is framed by the publication; on the right by the scores from which it takes shape, on the left by the editorial project that renews it belatedly.There are no hierarchies, there is no original, only an affective network that generates movement, among bodies, among identities, between the book and the performance. Rire, Laugh, Lachen and Laugh are two occurrences, along with the workshops, the children’s laboratory in Bologna by artist Elisa Fontana, the film N.O.body by Pauline Boudry and Renate Lorenz, both inspired by the Laugh project. They are two of the possible sources of resonance of an entity that, to use the words of the philosopher and social theorist Brian Massumi, manifests itself as an “organization of multiple levels that have different logics and temporal organizations, but are locked in resonance with each other and recapitulate the same event in divergent ways.” The plural authorship of the compositional sequence coexists in the body of the artist and the editorial space, manifesting itself in the variation of laughter and the gestures of the staging, in the multiplicity of notational forms and in the handwritings of the publication. Contact with the performance, conveyed by the “and”, makes the book a device capable of interfering with the social and cultural conditions of the present; Rire, Laugh, Lachen is an invitation to inhabit others’ bodies, laughter, to multiply, to disguise oneself. In contact with the book, Laugh survives the present. As Antonia Baehr herself states, “Laugh is an ongoing project with many tentacles.”

The existence dedicated to the present of performance in the encounter between bodies and the greater validity of direct experience do not resist the impact of the work. [5] The condition of transience and the escape from the archive promoted by Peggy Phelan as identifying features of performance are renewed in the project, but in a nomadism that also involves editorial materials. The excess of the affective dimension takes the place of that of the bodies, making the performative work available for a re-editing process that also passes through the double page. Beyond the mere archival dimension of publication, in a viral ontological perspective [6] of performance, that “and” makes room for new alliances, new connections in difference, a multidimensional system outside hierarchy. Rire, Laugh, Lachen, and Laugh live in and of horizontal coexistence.

[1] I list them in the order of appearance: Christian Kesten, William Wheeler and Nicole Dembélé, Henry Wilt, Manuel Coursin, Naïma Akkar and Antonia Baehr, Valérie Castan and Antonia Baehr, Sylvie Garot and Antonia Baehr, Bettina von Arnim, Ulrich Baehr, Frédéric Gies, Antonia Baehr, Steffi Weismann, Andrea Neumann, Isabell Spengler, William Wheeler, and Stefan Pente.

[2] An electronic musical instrument that does not require physical contact by the performer. Invented in 1919 by the Soviet physicist Lev Sergeevich Termen, the theremin consists of a enclosure containing electronic components and two metal antennas that control the pitch and volume of the sound. The musician manipulates the waves generated by the antennas with their hands, producing different sounds ranging from vocal timbres to those of a violin.

[3] From the Greek word ἔκϕρασις, derived from the verb ἐκϕράζω, meaning “to explain, describe, describe with elegance,” from ἐκ “out” and ϕράζω “to speak”, the term refers to the verbal description of a work of art.

[4] The description, which reworks the ekphrasis by dramaturg Lindy Annis, seizes the artist Antonia Baehr’s invitation to generate new openings and survivals. See Lindy, “J’aime rire. Je ris souvent. On me voit souvent rire.” In Antonia Baehr, Rire, Laugh, Lachen: 10–22.

[5] I do not intend to deny the differences that exist between the two perceptual experiences, but rather to propose a revision of the ethical and ontological hierarchy underlying Peggy Phelan’s reflection.

[6] The term is coined by Christopher Bedford. See Bedford, “The Viral Ontology of Performance.” In Perform, Repeat, Record: Live art in history, by Amelia Jones and Adrian Heathfield: 77–87.

Bibliography

Baehr, Antonia. Rire, Laugh, Lachen. Paris: L’Oeil d’or; Les Laboratoires d’Aubervilliers, 2008.

Bedford, Christopher. “The Viral Ontology of Performance”. In Perform, Repeat, Record: Live Art in History, by Amelia Jones e Adrian Heathfield, 77–87. Bristol; Chicago: Intellect, 2012.

Jones, Amelia. “‘Presence’ in Absentia: Experiencing Performance as Documentation”. Art Journal 56, no. 4 (1997): 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.1997.10791844

Jones, Amelia. “‘The Artist is Present’: Artistic Re-enactments and the Impossibility of Presence.” TDR/The Drama Review 55, no. 1 (Spring 2011): 16–45. DOI: 10.2307/23017597

Jones, Amelia, e Adrian Heathfield. Perform, Repeat, Record. Bristol; Chicago: Intellect, 2012.

Massumi, Brian. Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation. Durham; London: Duke University Press, 2002.

Massumi, Brian. Politics of Affects. Cambridge: Policy Press, 2015.

Phelan, Peggy. Unmarked the Politics of Performance. London: Routledge, 1993.

Phelan, Peggy. “The Ontology of Performance: Representation without Reproduction”. In Unmarked. The politics of performance, by Peggy Phelan, 145–148. London: Routledge, 1993.

Phelan, Peggy. Mourning Sex: Performing Public Memories. London: Routledge, 1997.

FEIQ – Independent Queer Publishing & Performative Practices Festival

Produced by TANK – Serbatoio culturale

Curated by Marzia Avallone in collaboration with Guendalina Piselli

Sunday, October 1st

2PM–2AM

at Tank – Cultural Reservoir, Via Emilio Zago, 14, Bologna

NO AICS card required / Participation fee of €7

Public Programme

Book area |2PM–2AM|

Publishers: NERO, META publishing, Kabul magazine, Frab’s magazine, Igor libreria, Dame magazine, D editore, TLON, TBD magazine, Tamu Edizioni, Frankestein, Krisis publishing, Trans Muted, Menelique, Masseria Wave

Thematic Panel Publishing and Performance + Presentation of Queer Pandèmia (TLON editions) |4PM|

Talk with Nicola Brucoli, Carlo Battisti, Caterina Di Paolo, Simone Marcelli Pitzalis, Mariolina Catani, Andrea Zardi, moderated by Marzia Avallone.

A reflection on the interconnections between publishing and performative practices in the contemporary art scene from a queer perspective. On this the occasion, Queer Pandèmia, a transdisciplinary project published by TLON editions, will be presented. It aims to bring greater queer representation into the world of art, showing young artists and authors from the LGBTQIA+ community and involving different creative realms and sectors in a blend that promotes dialogue, inclusion, and contamination.

Performance Pulse (20′) |6PM|

Solo by Andrea Zardi / ZA | DanceWorks curated by Mariolina Catani, performer Riccardo De Simone, DJ set Cecilia Stacchiotti. A reflection on the concept of community today, which undermines individual identity. Pulse is the name of a club, of the heartbeat, of the breathlessness, of the rhythm of people dancing, a vital pulse, a gunshot. It is also strength, energy.

Clubbing Moments |7PM|

With:

Duo Sarabamba > dj set Techno

Bootstrap e SL/03 (resident TANK) in b2b > dj set Techno, Hard Techno

Nove9Nueve > dj set ethnic music, Techno

Xaxer > dj set experimental club, left-field, peripheral rhythms, broken beat, footwork, new club music

Vegan Food |6PM–11PM|

Curated by “La zappa e il mestolo”

More information about the festival