Hearing with Eyes Closed

A conversation with Zimmerfrei on cities and family affairs

ZimmerFrei is an Italian artist collective that has been working together over the past two decades, whose practice crosses various artistic languages and disciplines, from video art to installation and performance art, as well as documentary cinema and experimental theatre. Last February they presented the 15th episode of Family Affair at Teatro India in Rome, a project based on a participatory theatre format involving local families in a two-week workshop and a live performance. From today on, ZimmerFrei has made the work available for streaming on #TdROnline.

Family Affair has previously been traveling through many cities and countries, from Portugal to Poland, from Belgium to Egypt and China. The work is an attempt to respond to a question the artists originally asked themselves: how do people live their lives in present times and what is family today? The point was not to give a direct answer, rather to multiply all the possible answers by collecting stories and fragments of experience. Family is not intended here as a biological group of people, nor as an abstract concept, but rather as a tangible network of intertwining relationships that bind people together. Every case draws a unique constellation.

The live performance is mainly based on oral narration and functions like a listening device, in which different voices reverberate. Short stories, anecdotes, futile events, names of people and places, blend together in a single flow. At times, a glimpse of the city comes through this murmur of words and sounds, and a sentence, or even a single word—like a spark—could trigger a private stream of memories in the viewers as well.

Today Family Affair is also a large archive, accessible in the form of a video installation, that gathers the many materials recorded by the artists over the last five years. Through the stories of these families, this archive allows many other topics to get to the surface, such as memory and legacy, the passage of time, and the relationship between community and territory.

Maintaining the same attitude that already characterized the documentary films realized in the past, ZimmerFrei remains faithful to reality to explore how narration emerges from life and how stories can proliferate and propagate, while activating processes of thought and imagination.

Assuming that life should always be understood as a shared living, we could affirm that telling stories reveals itself as a practice of shared thinking. Quoting Donna Haraway, “These are the times we must think; these are the times of urgencies that need stories.”

Courtesy ZimmerFrei.

Marta Federici: You started working on Family Affair five years ago. I would like to go back in time with you, to understand how this project was born and why. Which were your expectations at the beginning, and how did it go?

Massimo Carozzi: We started talking about this project in 2015. At that time we used to travel quite often, and that type of life had repercussions on our families. Our personal experience was certainly an important component for each of us, in different ways.

Anna de Manincor: We invented a fantastic definition: “on-and-off family.” We were posing ourselves many questions on how we live, especially because of the way we used to live in those years: spending a lot of time together. By working together, and often working abroad, we used to share a consistent chunk of our daily life. We were sharing houses, doing the same things, like a team or a family. We share a fate. For me, this is family: coming from the same place and going to the same direction, despite everyone else doing all sorts of different things. We were wondering how the hell do we live while we handle so many different things?

At that time, we were working on a series of city portraits, therefore our gaze was directed towards territories. But we always read places through people. What happened then was like a shift in the gaze. We didn’t stop exploring places, but we purposely decided to have a direct relationship with the people who inhabit it. Since we couldn’t say how we live ourselves, we decided to ask others. We became interested in families as narrative units. We didn’t care about the psychological aspect of their relationships, I mean the psychoanalytic issue.

Family Affair at Teatro India, Rome 2020. Courtesy ZimmerFrei.

While thinking of Family Affair, another work of yours came to my mind. Stop Kidding is a video installation from the early 2000s, it is composed by the portraits of forty-three people who pronounce, one after the other, one blunt sentence, almost a verdict: “I will not have children for this country.” As you pointed out, that work was born in response to the Italian political situation of those years, in which Berlusconi returned to power as prime minister, for his second mandate. You described Stop Kidding as “a work that is at once loving, angry and touching.” Is that video still effective for you today?

AdM: I haven’t been thinking about it for ages. That work represents a particular case, because I did it by myself on the occasion of a small exhibition in Trento. In that period we stayed at TPO Euraquarium, a self-organized space that changed quite a lot in the last years, but still exists in Bologna. Out of the blue, the work was invited to the Venice Biennale and then reabsorbed into ZimmerFrei. It has the same structure as other works we made: a series of portraits, and then a very personal sentence, that reverberates by being adopted and repeated by different people. That was like a seed that then stemmed in many different ways. But the meaning of that sentence has now changed for me, in terms of personal feelings. In 2003, I could feel an external pressure, coming from a wider context and from society itself, trying to frame people in a specific kind of situation. If you were a woman, living in the first world, in a country like Italy, you were held to perform a duty. But you could decide to question it, or you could withdraw, and say—look, I can also do otherwise. As a female you are usually identified within this potential, but once you take it in your hands, you can also deny it.

Nowadays, in my opinion, there is a different external pressure towards those who are in their twenties—that was my age at that time. The pressure doesn’t fall any longer on starting a family, putting your head in place, and making children. It is almost the opposite. Today the pressure has shifted on work, production and self-sufficiency. So, now, a woman living in the first world, in Italy, twenty-five/thirty year old, has almost the opposite problem: she can choose to do things that are not productive or that can be productive otherwise. This situation has just begun. At the moment, both kinds of pressure are present, one may be stronger than the other according to the way you feel, the family you have, the context you live in and your age. Anyway, yes, the situation has changed. Obviously these considerations are valid for women like me, not for everyone.

If that work would have been made today, perhaps I would have said otherwise—I will have ten children at eighteen, fuck this all! Among the stories in Family Affair here in Rome, there is a couple in their twenties who have a two-year-old daughter. For me they represent the present. She was pregnant in high school, and they say: you know what, we will do it now, and then we’ll see how it goes, day by day… then we will send her to work! [she laughs]

With Family Affair you have visited many cities, in different countries, and met many kinds of families. In five years, how did your attitude and your way of working evolve within the format?

AdM: At the beginning we were more worried about the performative aspect…

MC: …we tried to imagine a device that would allow us to bring stories and non-professional people on stage, in front of the audience. We didn’t want to bring a play, neither autobiographies, nor a reality show. We asked ourselves many questions about this issue.

AdM: …visiting people’s homes and shooting was never difficult for us. Each house we enter, we find a different situation. Sometimes everything happens in a very natural way, sometimes you have to find the right time to take out the camera. This part of the work is very similar to all the documentaries we had already done. It’s a negotiation between us and them, that happens, above all, in their territory. But when you bring these people on stage, you have to deal with all those expectations related to theatre. Five years later, the difference is that we have more confidence in the fact that the two-weeks we spend together working allow us to keep a standard that will never replace the competence one should have to make a show. What we do is another thing!

Family Affair at Teatro India, Rome 2020. Courtesy ZimmerFrei.

As you said, in Family Affair you follow an approach that you already had as documentary filmmakers. What does it mean to you working with reality? What are the affinities and what the differences of this kind of work in cinema and theater?

MC: When we started Family Affair, we had been working for five years with documentary cinema. We didn’t decide to adapt that methodology to theater. It was a natural evolution.

AdM: By now we know that we are not interested in fiction, nor in writing scripts. Obviously, sometimes we have precise ideas and we try to construct situations for something to happen… we did this many times, both with films and with Family Affair.

A few important elements come to my mind. Each documentary film is a prototype for both a possible film and for another impossible film; the documentary filmmaker must maintain two simultaneous relationships: one with the reality they come to encounter, and another one with the film they are developing; a documentary film always has a direct relationship with the viewer, with an implicit agreement of mutual trust and constant questioning—as in most of theatre shows, I would say.

Personally, I have experienced Family Affair as a listening device. The private life of the participants is not documented through the video footage, but it is rather an oral narration. We see the people on stage, giving their back to the audience, as they are speaking. This situation establishes a continuum between them and the seated audience. While life fragments are told, we listen together, and in that very act of listening, we become a collectivity. Orality is also linked to the themes of legacy and memory.

AdM: Yes, exactly, you interpreted perfectly their position on stage. This is something that we tell them from the very beginning, that they are the first spectators of what is happening on stage, and that they share the same posture as the people sitting in the audience. This setting frees the viewer, and people can also get distracted if there is something that resonates within them, which may take them into their personal flux of thoughts… In my opinion, the performance should encourage this. It’s not about getting bored, but rather following some kind of hint that is relevant to you.

MC: Oral story-telling is present in our practice from the very first moment we decide to stage something in front of the camera. It dates back to the first proto-documentary work we did in Milan in 2007, which was called External Memory. On that occasion we were looking for stories, but stories are told by voices. So we tried to understand how to treat this oral material, how to actually transform them into stories and micro-stories. We also wondered how these stories could generate an imagination in the people who hear them. This line of thought goes all the way to Family Affair. The excerpts we select from the conversations with the participants are not the strongest ones, emotionally. The family story becomes an epic tale once it leaves the nest, when it comes out of the house. There lay the issues of orality and legacy. Even a very small, apparently trivial thing acquires another meaning when it leaves the household.

AdM: The stories that are produced and handed down in families, or other kinships, constitute one of the layers of our common history—the history of the present, which will then become the history of the past, and so on. But usually within the private family situation, the interlocutor misses a witness/listener.

We are not interested in the most important stories, or the exemplary ones. In Family Affair, we select the stories that a family would never choose to talk about themselves. When those stories are told out loud by people who are not the protagonists, in that very situation, they suddenly move to a different emotional place. They fit into a much wider flow. Exactly at that moment, and thanks to that mechanism, those fragments of life can turn into stories. Not because you are a good storyteller, or because you narrate special things. The people we work with get most excited during rehearsals, not during the show: when they hear for the first time another member of their family adopting their own story, even a trivial one. As if they saw a part of themselves coming off. It is very touching, both for them and for us.

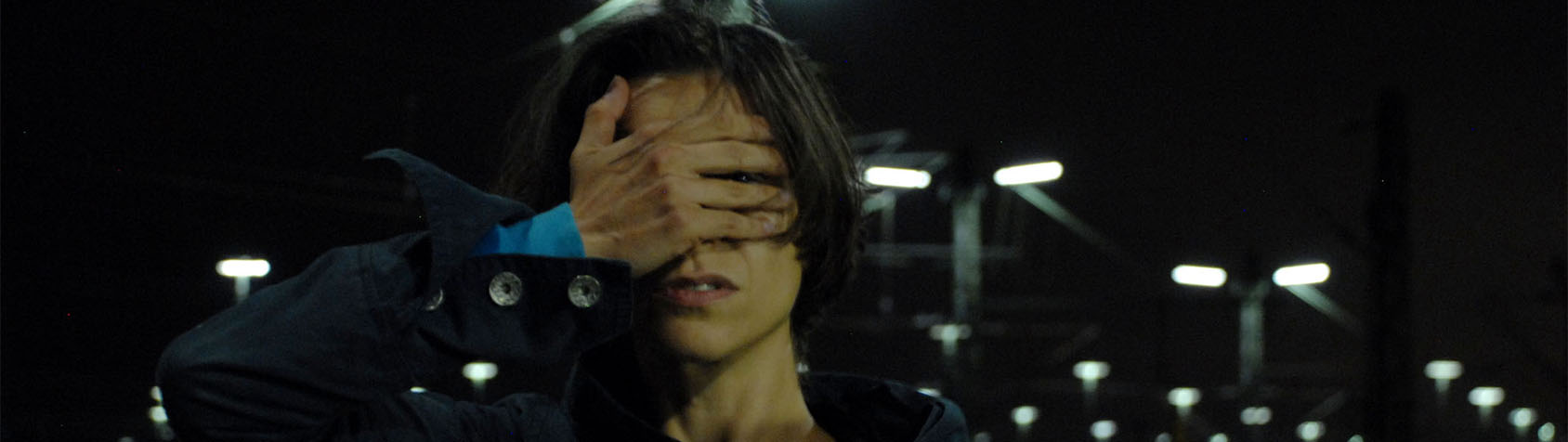

During the performance, a series of video portraits are projected on the backdrop of the scene. We see each member of the families sitting, with his/her eyes closed—as if they were listening. Why this type of representation? In an interview a few years ago you said something interesting, that you do not portray people but landscapes…

AdM: In Family Affair’s portraits we use a specific framing: plan américain (American shot), central perspective, lowered point of view, medium focal length, medium shot obtained by moving away from the subject—avoiding wide angle lens—if the space allows it. The eyes are closed, the subject is listening to the sound of the house and its inhabitants, who move according to their daily routine. Each portrait has a duration of three minutes.

Closed eyes have appeared in our works, photos or videos, since 2005. I don’t know why. In 2008 we won the Pagine Bianche (the old Phone Book!) award with a photo that is part of a 2005 series, where you see people covering their eyes with their hand. Thanks to that award we went to the ISCP residency in Brooklyn. Closed eyes also reappear in A study for a portrait, a work from 2006, in the film La beauté c’est ta tête, shot in 2013 inside a bar in Marseille, and also in our last film Almost Nothing | CERN Experimental City, where all the physicists and researchers’ portraits are linked by their closed eyes.

Closed eyes have a particular power, which acts both on those who are keeping the eyes closed but also on those who have them opened to look. Something similar happens when you look at someone who is sleeping, and you can perceive the fragility, the power over the other and the inability to fathom internal worlds. But I’m going too far.

The face is par excellence the subject of the portrait. However a face with eyes closed is mostly a landscape. You’re looking at something that the person in the image will never be able to fully tell. So you look at him/her as you would look at a place, a place where things happen(ed).

Panorama, Roma 2004. Courtesy ZimmerFrei.

I would like to focus on the experience in Rome. In your opinion what is the peculiarity of this Family Affair episode?

AdM: Working in Italy already makes a difference for us. When we work abroad, translation and linguistic mediation are always an issue to consider. Moreover, we are somehow fascinated by Rome, which is a strange kind of metropolis, perhaps not even a metropolis, but a sort of aggregate made of different neighborhoods. In the stories of these families, the river Tiber is a very strong presence. It is never mentioned when one speaks of Rome, instead it emerges just like a character. The Tiber determines much of the personality of the neighborhoods in which they live.

The families we worked with are very different from each other, they do not come from the theatre context, or even from a homogeneous cultural context. There is no identification between them, and neither are we similar to them. But we noticed that everyone here has taken a step back in order to listen to others. We thought about this situation. There are also very clear political orientations, very different from each other. For me, this is a proper portrait of Rome. Living together in Rome has this very feature…you have already learned to tolerate anyone! There are always people around who want to express their opinions, everywhere.You go out and it’s an endless show, it’s really a jumble, and this is a peculiarity of a city as such, in my opinion. In Rome there has always been plenty of contrasts, and a lot of background noise. This attitude contaminates also people who move here, whether they are Italians who come from other cities or from the strip of territory surrounding Rome, or foreigners who come from other countries. It’s a very contagious thing. In the same way the Roman accent horribly sticks to everyone. [She laughs]

I’d like to know more about your relationship with Rome. You have spent a lot of time working here in the past years.

AdM: Our first work shown in the art world was shot in Rome, it was presented on the occasion of our first solo show hosted by the only gallery we have ever worked with, Monitor gallery. It is a circular panorama of Piazza del Popolo, inspired by pre-cinema views and by Philip Dick’s theories of parallel lives. In Rome we also have many friends, who have had and still have a great influence on us: the choreographer Michele di Stefano (MK), the director Alessandro Rossetto, the editor and now chicken breeder Silvia Bambagini Oliva, some actresses among the occupants of the Teatro Valle, musicians, artists who lived in Rome, the legendary Schifano’s house, clubs… There are some places that have been important to us: Rialto Sant’Ambrogio, Angelo Mai, Mattatoio, Palazzo delle Esposizioni, where we presented our first two-channel video installation in 2000. Massimo has a particular passion for some places, where we always go back to: Portico d’Ottavia, the English cemetery, a pizzeria in Trastevere called by people the “Obitorio” [the morgue]. I have an uncle who has lived in Rome since the early Seventies, in the heart of Trastevere. He has been a poet and a viveur of the Roman underground scene. He is the black sheep of my family (and of course he was my favorite one when I was a teenager). Born in a family of blacksmiths and stove manufacturer working in Trentino, he had fled to Rome “to make cinema”…

Family Affair at Nisyros (Christos and Loukia). Courtesy ZimmerFrei.

Your artistic practice is characterized by an attitude towards repetition: you often create works in series. For me, the choice of working in this way—repeating and starting over—adds an extra layer of meaning to the works. Can you tell more about this attitude? Where does a project ends and another begins?

MC: In fact if we look back, we mainly worked in series rather than on single works. Usually we are involved in at least two series at the time. Earlier I mentioned the documentary we shot in Milan in 2007. At that moment we had just closed the Panorama video series. For example, for those works we had to organize a performance, involving people, defining a temporal device. Panorama videos have a format suitable to be explored or interpreted in different ways.

AdM: Once you have defined the rules of the game, the time after you feel usually freer, and you have a deeper understanding of what you can get out of that game. If you make new rules every time, your artistic work ends up being limited to the device construction. Having a good idea is not our central issue. Our work cycles generally last four or five years. In this case we have slightly exceeded the regular duration. It usually happens that we are working on a series, and at some point another one starts, and it takes up more and more space within us, and the previous one slowly runs out.

MC: When we received the invitation by Francesca Corona and Teatro India, we were enthusiastic, although we were no longer thinking that much about Family Affair. Also because we had already begun a new cycle.

You mean Saga, the cycle about Bologna? How is that going?

MC: Yes, that one. A first version, which is divided into three episodes, should be released in June, on the occasion of the Atlas of Transitions festival in Bologna. Then it will be edited to become one film, to be submitted to film festivals. It’s going well. Then it will become a feature film, because we have been following a group of teenagers for two years now and during this time things have changed quite a lot. They have grown, they have integrated, One of them would have received Italian citizenship last month—he will get it as soon as the Covid-19 lockdown will get milder.

AdM: One of them came from Nigeria through Libya, and now he has just got his driving license. They are growing up so fast that we will have to shoot another film, if the film will premiere in August instead of June!

Saga, (Tea 25 aprile Pratello) Bologna 2019. Courtesy ZimmerFrei.

Interdisciplinarity is a very feature of ZimmerFrei, right from the beginning. You come from different backgrounds, and you have dealt with different kinds of situations, you worked with galleries, museums, theatre and film festivals. How was it to navigate among these different fields? Was it difficult? How has the situation changed during the past twenty years?

AdM: I think the situation did change. In my opinion now there are more people working with cross-media projects, compared to the early 2000s. Let’s say that at some point it has become a sort of trend… but people always try to frame you in a specific field. They ask you—so you work in theatre? Are you represented by a gallery? Then you have to be expendable as an artist. In the past years I felt this issue more strongly, also because we were younger, we were more under this kind of pressure. Sometimes they asked us—what if you will split? In that case your works will lose their value, because you have a collective name. In the theatre context this is normal, you are a company. But in the visual art field it is not considered as a good thing. It can be cool, but it is not a good investment, neither for a gallery, nor for a collector, nor for a museum. I always make this joke—a group that has been working together for twenty years has a longer existence than any average lifespan of an artist’s career or of any wedding! But we didn’t know this at the beginning. Before ZimmerFrei was born, we all had had an experience in live arts, music or theatre. It was more interesting for me to have an external identity than to use my own name, identified with my work. It makes you freer and it is more fun to create another “persona.” Sharing a common experience is the most precious thing now, because it makes you feel stronger and warmer.

MC: We have always continued to follow our ideas. We didn’t use any strategy. For instance, the experience of documentary cinema began within an European network of festivals and public art—within the In Situ network—which has produced that series of works, Temporary Cities—the city portraits. Each of those festivals works in a completely different way. In Budapest there was a certain situation and in France another… That network was interested in the way we were working: we shot a sort of a collective film, which engaged with a specific place, within the city hosting the festival that invited us; then, people we involved in the shooting, their friends and the place itself, were always the film’s first audience. The films have always premiered in the place where we shot, a site-specific cinema that was set up outdoors.

AdM: So you have a very strict responsibility on yourself, towards the people you have involved, towards their environment, and towards what we demand. You cannot say—I am the artist, I take my archive home, goodbye and good luck.

However, working this way can be difficult sometimes… for many years we didn’t have a real distribution, or a producer who’s always by our side, or an established company or anything like that… it’s me, him and those collaborators we manage to put together for each project. Obviously there are long lasting trusted collaborations, which are very good. But if I had to tell you what we have capitalized on in terms of relationships, contacts, credibility… it is simply distributed in many different fields, where instead you are supposed to have an intense relationship with each and everyone of these fields. You know, the more people see you, the more they relate to you, the more they know you. People may like you or not, but they know what you are doing. Instead, we decide to disappear for four years—because we are shooting in the experimental documentary field—and then here we are at Teatro India, just because we have so many friends around! [she laughs]

MC: That kind of pressure related to presence was stronger when we worked more in the visual art field. It happened that we received comments related to this matter…

AdM: Living in a city like Bologna helped us, because it is neither Milan, nor Rome. That presence required in Milan or Rome, even if in different ways, is demanding. It’s the same in Brussels, or in Paris, or in New York. These are all cities where we have spent time, and each of them asks you—either you are there, or there will be somebody else taking over. Bologna is different, because it is not such a strong production center. People live in Bologna because they want to live in Bologna, that’s it. And therefore everyone has already an answer to that question… saying, leave me alone! If we decide to meet, it’s because we really want to!

MC: For example, when I’m in Bologna, I don’t attend the art world or the theatre context that much. I am mainly interested in music, therefore I follow that context. Most of my friends are musicians, or people who love listening to music.

AdM: I’d say that the most positive thing in this way of surfing, is that we have never stopped working. By catching the opportunities there where we found them, there was not even a day we didn’t work. We never identified our work with money or with success. This is my very goal: to be able to choose projects, to be free to propose things when people and opportunities come to you. We can invest all our time in doing this, so we can be focused. Nevertheless it would have been beautiful to have twice the time we had to do the things we did. For me this is very satisfying. I don’t know if this type of path could be reproduced starting today, because the whole situation has changed.