Group Therapy

When the experience is immersive and therapeutic, visiting a museum can be a self-optimizing activity. Can the museum activate a sense of communal purpose?

“With a church on one side and three hospitals on the other, the Frye Art Museum is embedded in an archipelago of institutions devoted to care of one kind or another. Like many art museums worldwide, the Frye has in recent years absorbed some of the functions of its neighbors, augmenting its traditional cultural offerings with mind-body programs such as weekly Mindfulness Meditation and yoga classes. This can be seen as a natural extension of its role within the community, as a space for exercising perceptual, intellectual, and emotional capacities, but it is also a reflection of the ways cultural institutions have expanded in order to remain relevant and responded to the pressure to demonstrate measurable social benefit.

To that end, in 2011 the British Arts Impact Fund undertook a twelve-month study, which showed that people “who visit cultural institutions and are most in contact with art are 60% more likely to feel healthier” than those who do not and are not. However it reached these conclusions, the fact that there was need for a study to prove art’s value is telling, as are the terms in which that value, or rather efficacy, is communicated. If art and art museums were once thought of as intrinsically “good,” edifying social instruments of moral redemption, as cultural critic Dave Hickey lamented in a prescient vocabulary (“What if art were considered bad for us?—more like cocaine that gives us pleasure while intensifying our desires, and less like penicillin that promises to cure us all?”), it seems they must now prove themselves against the index of individuals’ feelings of physio-psycho-spiritual health. Visiting an art museum is now a self-optimizing activity.

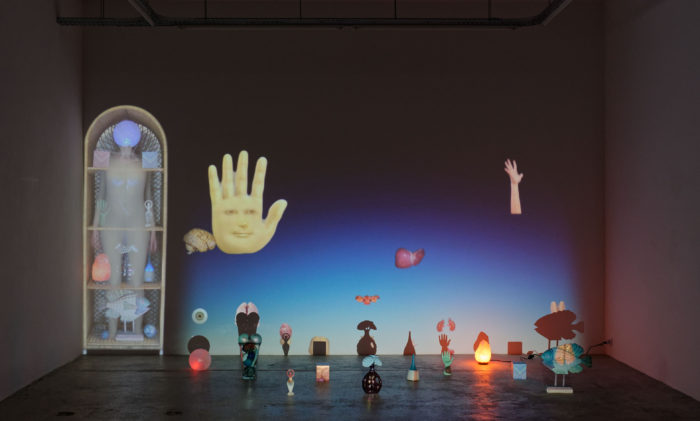

Group Therapy, Frye Art Museum. Photo Jonathan Vanderweit

Group Therapy, Frye Art Museum. Photo Jonathan Vanderweit

Group Therapy reflects on and exaggerates this trend, convening contemporary artworks in a range of media that comment on and/or adapt strategies of alternative medicine, psychotherapy, and the wellness industry. The exhibition centers on interactive and immersive therapeutic experiences and serves as a platform for public programs led by artist-practitioners, amplifying the museum’s expanded social role. By so doing, the exhibition both analyzes and participates in a broader zeitgeist of popularized psychology, self-care, and natural healing—marked by an explosion of interest in everything from personality type tests, self-improvement podcasts, meditation retreats, spa treatments, and juice cleanses to crystals, astrology, Reiki, and ayahuasca ceremonies—that has evolved out of and in response to a century-long shift away from traditional, communal belief forms toward a neoliberal ethos centered on personal growth and self-expression.

The twelve artists presented in Group Therapy respond to this current state of affairs in a variety of ways. Some look critically at the intersection of consumerism and wellness practices or examine the ways in which popular culture operates as a repository for psychological projections of desire, fear, and bias. Others pursue democratized, relational models of care within the experimental context afforded by art, raising questions about ethics, trust, and expertise, as well as the traditionally passive role of the spectator. Several engage psychological theories and alternative treatment methods to perform research in interpersonal and social dynamics or to seek the fringes of individual ego consciousness and avenues of escape from its limitations.

Maryam Jafri, Depression, 2017. Courtesy the artist and Kai Matsumiya Gallery, New York

Perkins Gilman’s feminist short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892), in which the shut-in protagonist imagines there are women creeping around in the wall and that she is one of them. In Moulton’s take, Cynthia regains connection to the outside world by ascending a giant redwood tree through a hole in the wall of her home.

The desire and struggle to bridge the interior of the self and the exterior of the social realm also animate Wynne Greenwood’s video installation How we, I mean how I pray (2011/18), which suggests the architecture of a women’s spa—a space in which bathers are exposed to and vulnerable with others while having inwardly focused, self-care experiences. Visitors are invited to lounge together around video projections in the place of soaking pools on the floor; rather than reflecting the self as water would, these video pools present what the artist calls “loose prayers of noticing,” capturing everyday encounters within the artist’s studio and out on city streets. Medusa, the snake-haired monster of Greek mythology, and television character Pebbles Flintstone also make appearances, coming into dialogue to engage (and challenge) archetypes of feminine behavior and being. The notion of identification with mythological and popular characters—or the projective fantasies that inspire their creation—carries through to the next gallery, in Pedro Reyes’s Los Mutantes (2012), which takes the form of a periodic table of anthropomorphic creatures invented by various cultures across time.

Liz Magic Laser, Primal Speech, 2016 (video still). Courtesy the artist and Various Small Fires, Los Angeles

Cindy Mochizuki’s participatory Fortune House (2014/18) further unfolds the ways in which symbolic figures help us understand ourselves, beginning with a personalized reading in which the sitter’s destiny is interpreted through the archetypes of the tarot. Mochizuki offers the tarot readings in exchange for a monster story drawn from the participant’s own memories or dreams, old myths, or thoughts about what might qualify as a monster in contemporary society; she then translates the story into an inkblot drawing, symbolically neutralizing the monster’s negative power over the sitter and conflating divination practice with an image form associated with psychoanalysis. Associative psychoanalytic methods also inform Reyes’s Museum of Hypothetical Lifetimes (2011), which formalizes Jungian sandplay therapy, wherein individuals create representations of their internal worlds by arranging small figures, of subconscious significance, in a tray of sand. In Reyes’s version, participants work with a trained (but nonprofessional) facilitator to select from among hundreds of small objects and place them in a scale model of an imaginary museum with twenty-two galleries representative of “mother,” “the classroom,” “aging,” and so on, creating a retrospective and prospective “exhibition” of their lives. The work is one of sixteen therapeutic activities that make up Reyes’s Sanatorium project, a “temporary clinic” that aims to democratize and destigmatize therapy and to tap into the capacity of members of the general public to help one another.

Ann Leda Shapiro, Trio, 2016. Courtesy the artist

Following this potentially intense experience of self-narration, visitors enter the final passageof the exhibition, which immerses them in sensory experiences and visualizations that plug into ancient forms of knowledge and deeper, interconnected consciousness. Two moving-image works by Joachim Koester inaugurate this section, exploring the terra incognita of the body and potential routes of access to the underlayers of the mind. Tarantism (2007) captures a contemporary interpretation of the tarantella, a spontaneous, convulsive medieval dance that was thought to cure victims of delirious symptoms caused by the bite of a tarantula. Reptile brain or reptile body, it’s your animal (2012) engages the theories of Polish writer and theater director Jerzy Grotowski (1933–1999), who developed mind-body exercises inspired by Haitian rituals and yoga to help performers get in touch with the “reptilian” or primitive brain. In the next room, Lauryn Youden’s A place to retreat when I am sick (of you) similarly revives esoteric healing knowledge—especially marginalized traditions historically associated with women (i.e., witches)—while utilizing the contemporary neurological method of binaural sound therapy to calm the overstimulated modern mind. Intended as a communal space for meditation, Youden’s piece takes the form of a site-specific, Zen-gardenlike circle of combed black sand dotted with selenite crystals and pots of blended herbs, surrounded by cushions with wireless headphones, and crowned with a mesmerizing reflective wind-spinner sculpture. For Youden, the creation of the installation is a ceremonial process that functions as a method of self-care and a means of offering relief to others.

Shana Moulton, My Life as an INFJ, 2015–16. Courtesy the artist, Galerie Gregor Staiger and Galerie Crèvecoeur, Paris

Shana Moulton, Feed the Soul, 2016. Courtesy the artist, Galerie Gregor Staiger and Galerie Crèvecoeur, Paris

The surrounding paintings on paper by Ann Leda Shapiro, an acupuncturist as well as an artist, reflect her deep knowledge of traditional Chinese medicine and interest in talismanic, ritual-based art practices such as Ethiopian healing scrolls and Cycladic goddess figurines. Several of her included works were created for particular bodywork clients, as visual invocations of healing that represent the restoration or “making whole” of the subject’s fragmented mental, physical, and spiritual state. Another group of her paintings depicts encapsulated, hermaphroditic figures, symbolizing the artist’s belief that we each contain all aspects of being and exist as microcosmic reflections of larger ecosystems and the universe. Utilizing hypnosis to reconnect participants to these universal affinities, Marcos Lutyens’s sculptural audio installation Library of Babel, a Symbiont Induction (2018) focuses on mycelial colonies—complex underground masses of fungal filaments that form a communicative network and symbiotically share nutrients with neighboring plants—as models of mutuality and interrelation. The installation centers on a life-size spiral staircase, the stair treads of which are fruiting with reishi mushrooms, inside a mist-filled terrarium surrounded by comfortable seats. Spoken by the artist, the inductive audio track focuses on the staircase as an “architectural interface” by which to ascend and descend between hypnotic states and as a symbolic form connected to the notion of recursivity explored in Jorge Luis Borges’s short story “The Library of Babel” (1941). Lutyens’s project is motivated by a utopian desire to push aside what he has called “the bullying, obsessive-compulsive conscious mind” and open up new perceptual pathways that might be scalable from individual experience to the collective community.

Joachim Koester, Reptile brain or reptile body, it’s your animal, 2012. Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali, New York

Concluding in this way, following a through line of immersive group experiences, peer-to-peer participatory projects, and public workshops, Group Therapy reflects on the museum’s capacity to go beyond moralizing and self-optimizing models of engagement and activate a sense of communal purpose. Museums are mirrors of culture past and present, not instruments of direct social change, but they do assemble temporary communities based in (shared) curiosity, which is the necessary precondition for caring. The art institution’s greatest strength might be its ability to help that community recognize itself as such by reflexively magnifying the role of the spectator.”—Amanda Donnan, Curator, Frye Art Museum