Fight Against An Image

On Jacopo Rinaldi’s “iio sono un disgraziato il mio destino è di morir in prigione strangolato”

iio sono un disgraziato il mio destino è di morir in prigione strangolato exhibits at BRACE BRACE a new series of artworks, all coming from the artist’s research on Gaetano Bresci (the anarchist who shot and killed Italian king Umberto I). Jacopo Rinaldi’s work arises from an historical analysis that recalls the aseptic approach of forensic studies, as the first step of a broader on-going research.

“Since Balzac believed man was incapable of making something material from an apparition—that is, creating something from nothing—he concluded that every time someone had his photograph taken, one of the spectral layers was removed from the body and transferred to the photograph. Repeated exposures entailed the unavoidable loss of subsequent ghostly layers, that is, the very essence of life.”—Nadar

“Let’s consider the most basic case of indexicality: the passport photo. Everyone knows that nothing on earth looks less like us than our passport photo.”—Umberto Eco

In her book On Photography, Susan Sontag reflects extensively on the inherently aggressive nature of the photographic act. According to the famous critic, the camera is comparable to a weapon which we point at the environment that surrounds us and which allows us to establish “a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge—and, therefore, like power”. This same threatening character questioned by Sontag is on the contrary valued and enhanced by sales promotion of new photographic equipment throughout the twentieth century. Indeed, it is not uncommon to find explicit parallels between photography and firearms in advertising posters and ads. Like a gun, the camera is often offered to buyers as a predatory tool, easy to use and at the same time capable of enormously increasing the powers of the person who is using it—“Just aim, focus and shoot”.

This sort of metaphor already appears in a Kodak advertising poster from the late nineteenth century. Designed to sponsor one of the first models of pocket cameras released by the US multinational company, the ad plays on the ambiguity of the gesture of a man, who grabs his camera and takes it out of his pocket with the exact same posture of a cowboy that pulls a pistol out of the holster. The image has been chosen by Jacopo Rinaldi to present his new solo show, hosted by the artist-run space BRACE BRACE, in Milan. Titled iio sono un disgraziato il mio destino è di morir in prigione strangolato (literally, I am a wretch, my destiny is to be strangled and die in prison), the exhibition brings together a group of new works, all part of a project that investigates the figure of Gaetano Bresci, an Italian anarchist militant who is known to most people for having shot King Umberto I di Savoia in the summer of 1900.

The artist’s interest in his story sparked almost by accident: by reading some newspapers and articles of the time he learned that the regicide had a passion for photography. Bresci actually owned a camera, which is now kept at the Criminological Museum in Rome, where it is displayed in a small showcase together with chemical baths for photographic processing and the revolver he used to kill the king. The eye for detail is a typical trait of Rinaldi, whose artistic practice follows a hybrid methodology that combines an aptitude for historical research along visual art languages. The study of the past and the use of archival materials are common to many of his works, which nevertheless retain the freedom of reasoning typical of art, and are never aimed at a philological reconstruction of mere facts. The artist’s creative process always unfolds by temporal twists and twirls, and follows unconventional narratives that tickle the shadows of memory, in order to trigger a new dialogue between the past and the present. Also in the case of this exhibition, a seemingly marginal fact is transformed into a lens able to open unexpected points of view, that allow the artist to retrace a historical event, occurred over a century ago, on the basis of deeply contemporary considerations.

The historical records and testimonies about Gaetano Bresci collected by Rinaldi convey the portrait of an elegant and handsome man, interested in politics and passionate about life pleasures. Bresci was nicknamed “the dandy” by his anarchist comrades for his well-groomed appearance and lifestyle. While living in Paterson, United States, where he stayed for two years, he learned English and was intrigued by the American lifestyle, unlike most Italian immigrants. He often had his camera with him and he loved to take portraits of his lovers, of his family members, but also of strangers he happened to meet during his travels. As Berenice Abbott wrote “the photographer is the contemporary being par excellence; through his/her eyes the present becomes the past”; we could then imagine that Bresci may have wanted to embody the ideal of the modern man—a man in tune with his times. Perhaps photography responded in some way to a desire to firmly grasp reality, a feeling not that different from the one that later would lead him to kill the king.

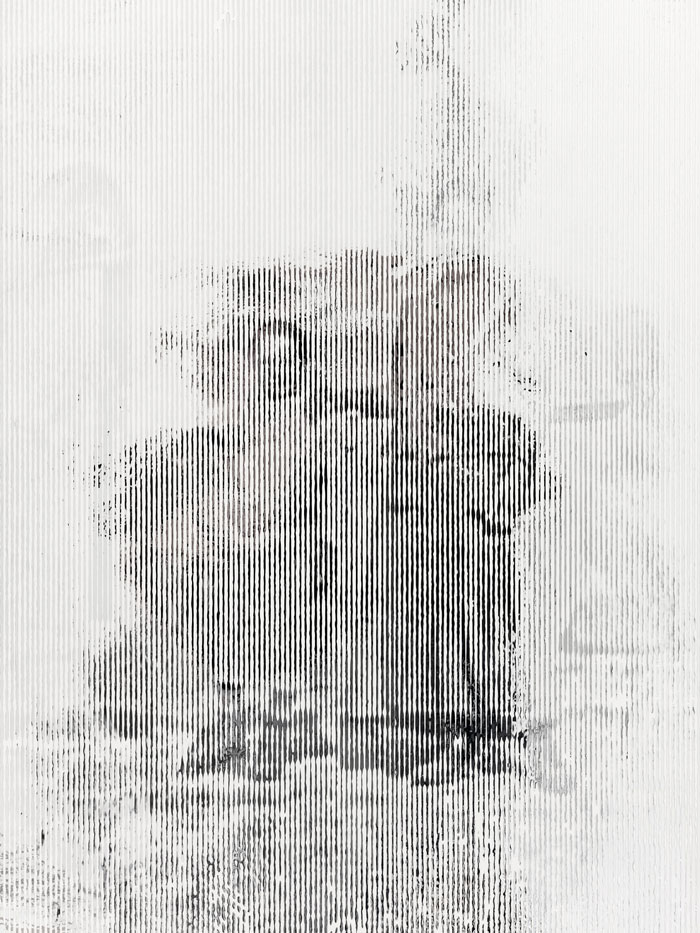

It is very difficult to get an idea of how Gaetano Bresci looked at the world, because most of his photographs have been lost. Rinaldi managed to track down five of them, which were probably taken by the anarchist in the weeks immediately preceding the murder, and which depict some people posing outdoors, perhaps his relatives or friends. For this exhibition the artist has worked on two of these pictures that have been scanned and digitally manipulated, in order to obtain the large-format prints installed on the walls of the space. Visitors can see a series of evanescent figures broken down and recomposed by a grid of thin strips made of mirroring contact paper, which adheres to the wall like a skin. These presences made of light have a vaguely ghostly effect, as they show themselves poised between emergence and dissolution.

On the original copies of the photographs reworked by Rinaldi, the signs of Bresci’s fingerprints are visible, as they were probably imprinted by mistake on the photosensitive surface during the film development. The importance of this detail is central in the economy of the artist’s pieces, and it can be read both metaphorically, where the fingerprint can be understood as an allusion to the theses about the indexical nature of photography, and literally, as a physical trace of the anarchist’s body, who is identified as a criminal subject after the murder.

Between the 1970s and 1990s, the concept of indexicality was widely used in the interpretation of photography. Scholars and art critics took this notion from the writings of semiologist Charles Sanders Pierce, who had divided signs into three groups: indexes, icons, and symbols. In his classification, indexical signs are distinguished from the others by the concrete relationship that binds them to their referent—the object they stand for, or refer to. One can list among indexes fingerprints, footprints, the shadow cast by a body, as well as the analog photographic image, since it is concretely originated by the recording of a luminous imprint projected by someone or something. In the interpretation of Rosalind Krauss, Philippe Dubois and others, indexicality establishes the ontological basis of the photographic image, and guarantees its documentary status and undeniable veracity.

In more recent years, art theory has expressed other opinions, emphasizing the complex and ambiguous nature of the relationship that links the photographic and the real, especially in the digital age. However, from a historical point of view, photography has brought about an authentic epistemological revolution in many disciplinary fields, precisely because it is considered a device for recording and attesting the truth. As analyzed by aforementioned Susan Sontag, photographs have profoundly altered the way we perceive the world we live in, causing a twist of our gaze. Given the possibility of capturing and possessing fragments of reality in the form of images, people ended up perceiving reality as a whole, like a document to be examined and an object to be controlled. As Sontag wrote “the photographic exploration and duplication of the world fragments continuities and feeds the pieces into an interminable dossier, thereby providing possibilities of control that could not even be dreamed of under the earlier system of recording information: writing.” And indeed, photography soon proved to be not only a tool for collecting private memories, or a new artistic language, but also a precious source of knowledge and an effective equipment for acquiring visual data that could be stored, catalogued and then used for the most various purposes, from police investigations to scientific research.

While retracing the events related to the killing of Umberto I of Savoy, it was evident to Rinaldi that the boundary between the different functions of the photographic image can sometimes be blurred and uncertain. In the case of Gaetano Bresci, photography suddenly turns from a private passion into a weapon in the hands of law enforcement. In fact, when Bresci was arrested after the regicide, pictures provided circumstantial evidence to track down his supposed network of contacts and collaborators, and the photographic eye continued to keep Bresci in check after his death, which took place at the Santo Stefano penitentiary, where a photographer was sent to immortalize the corpse. Meanwhile, the state government was exercising its control over and through images by following other kinds of strategies, such as forbidding the press to publish any portrait of him. A provincial newspaper was seized for having printed one in its pages. The “problem” was that, from an aesthetic point of view, Bresci’s person did not correspond at all with the stereotype of the mad or criminal man outlined in those same years by Lombroso’s criminal anthropology. The disclosure of the image of a well-dressed murderer with a well-groomed beard would therefore have caused the opening of a crack in the regime of visibility packaged by the authority with the support of science and photography itself. It is well known that in the second half of the nineteenth century photographic documentation was widely used in the investigation of social phenomena, and it especially contributed to the definition of the visual identity of those subjects who were designated as deviant.

These last considerations lead to the second interpretation of the fingerprints identified by Rinaldi on Bresci’s photographs. As mentioned above, on a literal level the fingerprints designate the body of the regicide committer, who, after being arrested, was subjected to prison discipline and was studied as a criminal subject. Cesare Lombroso himself became interested in him, and after Bresci’s death asked to receive his brain. The anthropologist had already dealt with other cases of anarchist militants in his studies, in 1894 he had published a book which tried to investigate the spread of anarchist political ideology through a biological-determinist perspective. Rinaldi has set an old edition of that book inside a thin hole dug in a wall of the exhibition space. Visitors can only see the spine of the volume, where the title, The Anarchists, can be read in golden letters.

Lombroso and his theory on the “born criminal” represent an era that was coming to an end. The next one recognized, at least formally, all the groundlessness of his method. But the investigations on Bresci’s body had already gone further. During his research, the artist also discovered that, when the prisoner was still alive, his fingerprints had been sent to the Italian consul in La Plata, in response to a specific request from the Argentine Anthropometric Office. At that time Argentina was the avant-garde of criminological studies. In the 1890s, in Buenos Aires, the anthropologist Juan Vucetich was in fact working on an advanced cataloging system of fingerprints, and he is actually the one who made the first criminal identification ever by using that method. Taking inspiration from Vucetich’s illustrated manual Dactiloscopia comparada, el nuevo sistema argentino, Rinaldi has created a limited edition print that reproduces the imprint of a human hand, that have been placed inside the drawers of a cabinet positioned in the center of one of the exhibition rooms, to suggest the presence of precious documents. The hand’s skin details are meticulously traced by a thin and dense silver ink veining which symbolically reverberates the mirroring surface of the works installed on the walls.

The story of Gaetano Bresci is situated exactly at the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth century, in a period marked by profound economic, technological and socio-political transformations. According to Foucault, the beginning of the twentieth century sets the apogee of the disciplinary societies, and we know that Bresci was imprisoned and died in the Santo Stefano panopticon, a famous Italian example of the architectural device which is described by the philosopher as the most meaningful metaphor for the same political model. Foucault was aware that a new type of forces were already in place in those years, triggering a slow but inexorable crisis of discipline, which would definitively collapse after the Second World War. “A disciplinary society was what we already no longer were, what we had ceased to be”, wrote Deleuze in his Postscript on the societies of control, referring to that moment of transition and following Foucault’s thought. In Jacopo Rinaldi’s reasoning, Bresci’s body records on its skin the invisible progress of those different forces. Indeed, the new usage of fingerprints in dactyloscopy seems to point out a substantial change of the surveillance strategies, which were already moving towards the creation of those databases characterizing the contemporary epoch. Bresci’s fingerprint cast a long shadow that traveled through time, until it reached the modern biometric recognition systems Juan Vucetich is one of the acclaimed fathers of.

Philosopher Paul B. Preciado has recently stated that we are still in a transitional phase. Control societies have not canceled the architectural devices of the disciplinary regime, but rather established unexpected alliances with them. The juxtaposition of multiple technologies, coming from different historical phases, is shaping new apparatuses of control of subjectivity, thus producing new forms of oppression and exclusion. Today’s hetero-patriarchal and racist rhetorics that construct gender, race, disability, mental illness and so on, still feed forms of prejudice that are not so different from the argumentations used by Lombroso to support his theories. The color of our skin, our religious or political beliefs, our sexual orientation, our social background, our “beauty” or our “ugliness”, are still instruments that are used against us to determine who we are. The complexity of our lives is flattened by essentializing and stereotyping processes into a series of two-dimensional images, in which we are reduced and captured—like in photographs.

While I was looking at the works installed by Jacopo Rinaldi on the walls of BRACE BRACE, I thought that the rarefied figures that inhabit them seem to oppose a refusal to the possibility of being understood completely, in a definitive way. They reject the possibility of an intrusive relationship: if you get too close, the shapes vanish and disintegrate into a series of dense irregular lines. Their evanescence reminded me that, after all, photographs are nothing more than a faded trace of the world, and that reality is something much more complex, which, fortunately, cannot be enclosed within an image. I then recalled something written by poet Éduard Glissant in his book Poetics of relation, where he questions the way Western thought is unable to accept people or ideas outside of a process of simplification, aimed at removing what is unknown and incomprehensible, and therefore considered dangerous. “In order to understand and thus accept you, I have to measure your solidity with the ideal scale providing me with grounds to make comparisons and, perhaps, judgments. I have to reduce”, Glissant explains. To understand (comprendre) often means somehow to own, and to dominate: in other words, we would literally say to grasp (saisir). As only poets can do, Glissant pauses on this verb, to evoke a vision capable of concretely communicating the meaning of what he wants to say. It is the aggressive “movement of the hands that grab their surroundings and bring them back to themselves. A gesture of enclosure if not appropriation. Let our understanding prefer the gesture of giving-on-and-with that opens finally on totality.”

The title of this text Fight against an image (Combattimento contro un’immagine) takes its cue from the famous exhibition Fight for an image (Combattimento per un’immagine), which was curated by Daniela Palazzoli and Luigi Carluccio in 1973 and took place at the Galleria Civica d’Arte moderna, in Turin. Among the first events in Italy dedicated to opening a broad survey on photography as an artistic medium, the exhibition proposed a first hypothetical reconstruction of the complex relationship that has been intertwining between reality and its representations through photography and painting, from the invention of the daguerreotype onwards.