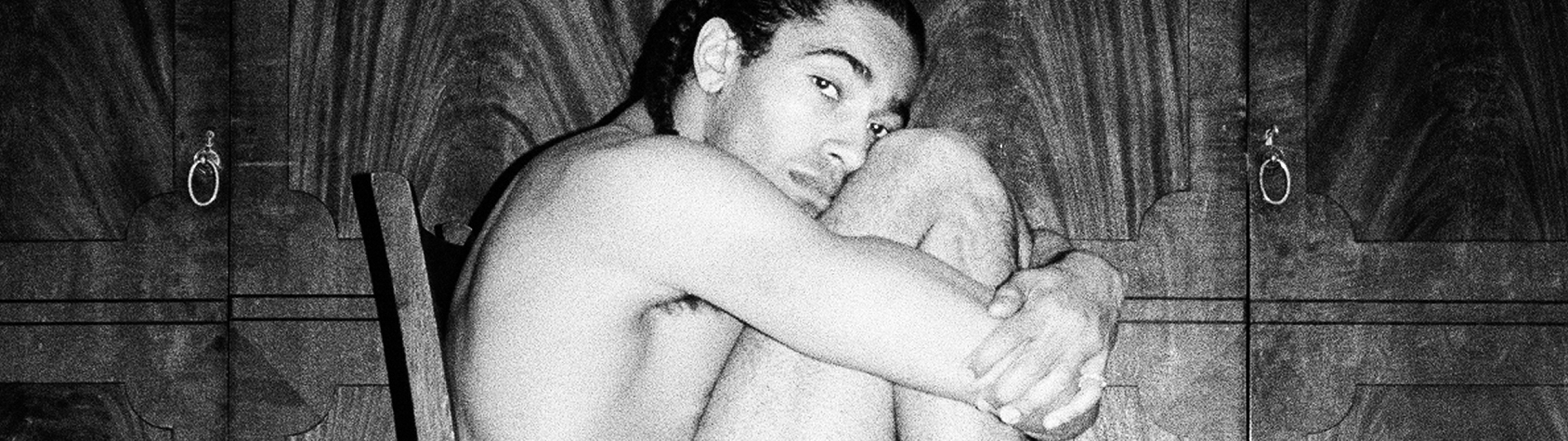

Fear vs Desire

A re-examination of masculinity

GRAY417C is a creative duo (Elisha Tawe and Mohamed Mussa) based between London and Amsterdam. The two artists have been in conversation through art, space and time for the better part of the last decade, interrogating the ways in which Black people have and continue to be portrayed across various forms. Through this process they have created works that pull from the long and storied histories of African people and their diaspora, attempting to re-imagine the positionality of Blackness in art and media. They communicate through a plethora of mediums, but film and graphics are central to their practice. Over the past few months, they have been actively interrogating the ways in which society expects Black men to perform masculinity and the impact of these expectations on their mental health. This line of research birthed a two-part short film titled The Mark Of Man.

Drawing on the works of Moya Bailey, Frantz Fanon and bell hooks the film aims to bring attention to the inner turmoil Black men face in day to day life through prose in both English and Kiswahili—the national language of Tanzania, the country they grew up in. The title The Mark Of Man is in reference to the veil of tradition that encompasses the gender which each of us knowingly or unknowingly carries forward. Through the film, they hope to inspire other Black men to undertake a quest for self-love and understanding, achieved through introspection and vulnerability, for it is vital we learn from the past, in order to affect change in our future.

From as early as I can remember the male patriarchal pornographic imagination has played a central role in determining how I and most men interact with the world. As young boys we are taught that domination is a prerequisite to masculinity, romance evokes the possibility of sexual activity and this sort of relationship must exist between man and woman. This indoctrination is often carried out through widely accepted practices such as sports, war games and the watching of TV programs and films. It actively constrains and boxes in young men, coercing them into the belief that who they are could not possibly exist beyond a specific binary. For Black men this process is intensified by white supremacy, the specification for masculinity is more stringent and its surveillance more active.

“You crept into my mind last night as I sat in Van Der Were park, causing me to reminisce about a time when you and I weren’t just you and I but rather ‘us’. A time when emotion triumphed reason and logic leapt out the window hurling headfirst towards the tarmac. A time when sitting on bedroom floors, industrial stairwells, dewy uncut grass, and park benches mounted to honor long-forgotten figures whilst detained in never-ending deliberation was a regular occurrence. When alprazolam freed us of all inhibitions and guided us through unhinged nights of unadulterated veracity. When Lucy would come knocking on our door and we’d answer her calls with open arms, surrendering our mind and body to her every demand. Deliriously following her down that dubious winding road of introspection; riddled with seven-story houses, with seven-panel windows each one allowing us to peer deeper into the depths of the duality of our consciousness.”

“Japokuwa hajui alipo,anatangatanga bila ya mwelekeo akitafuta sehemu ya kuwa pekee yake, Ya kuwa na utulivu wa akili, wakati anaingia kwenye makazi ya utamu na uchungu wa wasioamini na wenye kutafuta msisimko wa raha ya maisha. Mapenzi yasiyo na tija kuwafurahisha waliomzunguka kwenye jamii. Akipotelea kwenye unyevunyevu, na kusababisha kuchanganyikiwa kabla ya kuanza kujielewa. Uhuru wakati wa upweke. Matumaini katika nyakati za kushukuru. Je ni hali ya kutokuwa na majivuno? Je ni hali ya...”

“Though he doesn’t know where he is, he wonders aimlessly searching for solitude, peace of mind as one enters the bittersweet refuge left by non-believers and thrill-seekers. Hopeless romantics and crowd-pleasers. Drifting into the mist, pre-existing to exist. Liberty in instances of solitude. Hope in moments of gratitude. Is it a matter of modesty? Is it a matter of…”

Elisha: Making this film was a cathartic experience for me. I found masculinity as a socially constructed concept is something I had been grappling with for a while in my work. While trying to come up with the script for part one I remembered this poem I had written a few years back which was heavily inspired by Du Bois’s theory of double consciousness. It explored inner turmoil caused by external pressure and society’s expectations of me as a Black man in a rather covert and abstract way. I thought it just fit perfectly with the visuals. How did you find the process?

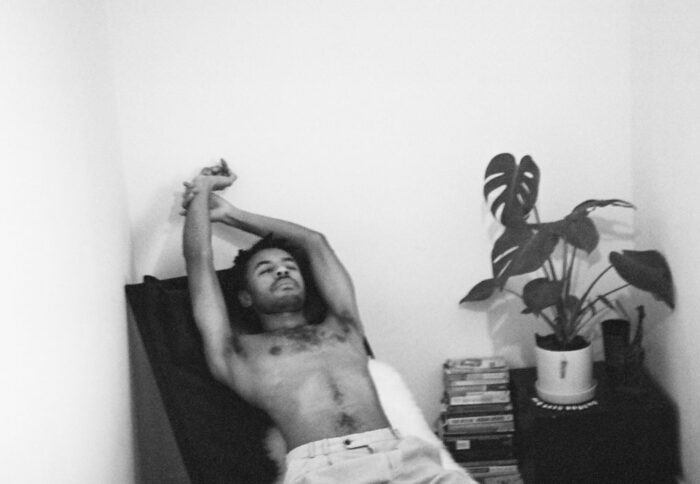

Mohamed: Yes, the turmoil that is caused by fear and desire is real and can have such a huge impact on your mental well-being and outlook on life. Seeing the idea through from its inception to its final manifestation was a thing of beauty. Making this film for me was an all-around enriching experience. This idea of who you are is constantly changing and that’s completely fine. If you want to experiment and try new things you should and see how they make you feel. But it’s a process and like all processes comes with ups and downs. You learn as you go along.

Elisha: Yes, I agree. It’s fluid, just like life, just like water. I think that’s why we had to shoot at the beach. We may not have fully grasped why we were drawn there during the process but I think it’s very obvious now. We knew we needed to depict that “fluidity”. There’s something very spiritual about the ocean.

Mohamed: I couldn’t agree more, being in a place where you can feel free and comfortable to act on these ideas. To know that it’s ok to feel the way you’re feeling. The ocean holds so much importance in my life now and it’s this process that helped me realize that.

Elisha: I’m glad this has had such a profound impact on you. The feeling of freedom in part two is amplified so much by the switch in language from English to Swahili. As Africans, I thought it was essential we did that. The first part feels heavy. I would liken the emotions that it conjured up in me to static from an old television. Breaking free from the bonds of colonial rulers that forced us to speak their language and expressing ourselves in an East African dialect that we grew up around, allowed the film to truly embody that freedom. That real return to self that I think we are trying to communicate.

Mohamed: It was imperative to have part two narrated in Kiswahili. Not only to showcase the grace and charm that the language has but also as a form of protest in an industry whose films often tend to be in western languages. I feel it was important to also have the film narrated in my mother tongue because It brings the conversation we are having to people back home, to see if these feelings were shared or dismissed, it opens a line of conversation to a topic that isn’t greatly interrogated. I remember when we were initially conceptualizing ‘Mark’ fragility and vulnerability were at the forefront of our conversations. I feel that part one captures this really well, what was your headspace like during the time of writing the prose that paired with it?

Elisha: The White Anglo-Saxon Protestant idea of masculinity brought over to us back in the days of colonialism has become the dominant framework on the continent especially in cities. While interrogation and looking to the future is key I think looking back at our histories could yield some interesting insights. Masculinity was a far more fluid thing in certain parts of Africa in the past. As for the prose, I was in a rather disjointed place in my life, trying to find balance. I was in the final year of my bachelor’s degree, actively trying to navigate that space. It was a sort of over-the-top piece that I had never really planned to share with anyone, but here we are. Was it difficult for you to acquiesce to the emotions that inspired the prose in the second part?

Mohamed: It was a difficult but necessary act. The prose helped me make sense of it all much more, it was very natural and free-flowing the words just hit the page. It was interesting to speak to my peers about the film and its inspiration. Their perspective further fortified how necessary it was for us to make this film. Exploring who you are and being at peace with it is key to building a bridge towards self-love. Vulnerability can be a sexy attribute if you allow it to push you forward.