Farming as a Work of Art

Agricola Cornelia was a farm founded by Gianfranco Baruchello in 1973, where art was meant to satisfy primal needs, and embody an utopia for both political action and poetics

On the occasion of the 20th anniversary of the foundation of the Fondazione Baruchello, the exhibition Agricola Cornelia S.p.A. presents for the first time the results and experience of the Agricola Cornelia, a farm outside Rome established by Gianfranco Baruchello, which may be said to have produced paintings, films, photographs, and books, as well as the more common agricultural products. Carla Subrizi compiled for us a selection from the book by Gianfranco Baruchello and Henry Martin How To Imagine. A Narrative on Art, Agriculture and Creativity [Bantam Books, New York 1985. (First edition: McPherson, New York 1984)]. See also Gianfranco Baruchello. Certains ideas (Electa, Milano 2014).

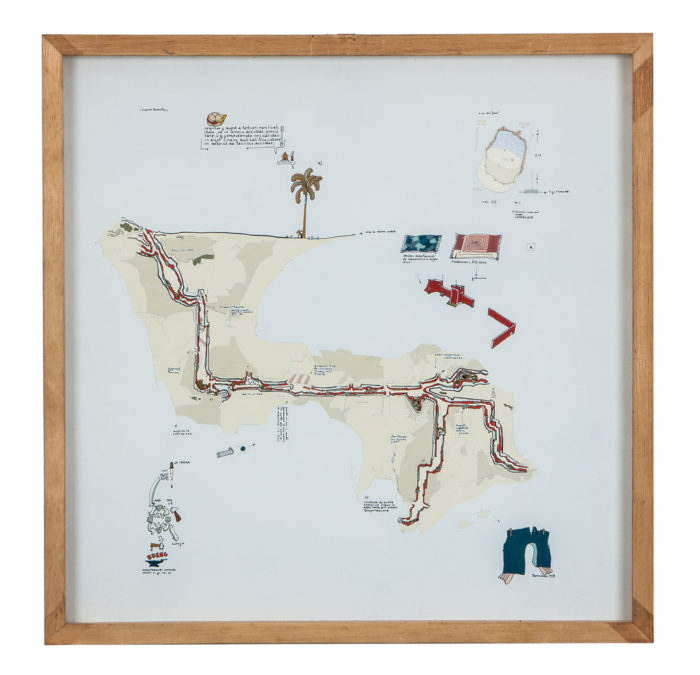

One of these paintings of Agricola Cornelia is a kind of general vision, a sort of bird’s-eye view, an exploded bird’s-eye view like those drawings of motors where you see all the different pieces that go into them. Well, this is that sort of vision of all the various pieces of land that we’ve cultivated here, the pieces that belonged to us as well as the ones that belonged to all our various neighbors, and right next to these fields I’ve written lists and descriptions of all the different produce that was grown on them. […] And over there there’s the field where we built the new gate and you can see in the painting how the road runs right alongside of it, and there’s also a note where it says that this is the field that I filmed from up in the attic, the film where you see the wheat as it grows through the course of a season. And aside from wheat, we also grew barley and com and chickpeas as well as two seasons of garlic, the first thing we grew there was chickpeas, which isn’t much to brag about since chickpeas will grow just about anywhere. […] This whole painting is a kind of general description of the whole operation of Agricola Cornelia, it’s a way, if you like, of remembering it all. It takes in everything from this sort of bird’s-eye view, and it’s all about the surfaces that we’ve dealt with here, just about the surfaces, these surfaces that sort of float in the mind without physical relationship to one another. […] The paintings though aren’t really the point, I haven’t even made a lot of them, what I’m talking about is Agricola Cornelia. And Agricola Cornelia is a great deal more than the dozen or so paintings of which it’s been more or less the subject matter. The paintings are a part of it, just as they’re a part of everything I do; they’re the one thing that’s constant in my work. Other things come and go, and the paintings are the place where they leave a trace behind them. I know, moreover, what painting is, and other people know what painting is, or think that they do, we share the illusion that we all know what it is, and so that’s no problem. But this time around, much more so than usually, the paintings are only a by-product. Agricola Cornelia is like that package of newspapers that I hung up five years ago in a tree. I don’t know what it is at all, it’s simply something that I had to do. The idea with Agricola Cornelia was to deal directly with the essence of an experience independently of the paintings. The paintings are something that I used to call attention to things, so why not be interested in the things themselves? Agricola Cornelia is like the anomalous objects or the photographs or the film of the empty room, it’s like all of the newspaper clippings, all of the things I’ve xeroxed, all of the various ideas I’ve had, all the notes where I’ve tried to make sense of it, notes on the earth as connected to grottos and speleology, on earth and death, earth as germinal primordial matter, notes on the things we’ve grown, the garden produce, sugar beets, wheat, barley, com, the sheep, the pigs, the cows, but especially, most especially, there have been all of these notes on grottos and caverns. […]

Agricola Cornelia S.p.A. Cattle breeding, 1976, photo documentation. Courtesy Fondazione Baruchello

The idea then that we’d do better to return to the earth as an almost polemical reply to the exploration of space is the idea that I really started out with in this adventure called Agricola Cornelia, or at least it’s the first idea I had that I still think of as fundamentally important. Everything before developed into it or didn’t develop into it, it was a way of making tabula rasa of the ideas that had come before it. It’s the idea finally against which all of my earlier notions had to measure themselves. And even though it didn’t just fall on me like a stroke of lightning out of a clear summer sky, it was still an idea that was more or less sui generis in the sense that it was just there and hadn’t grown out of any legible context. And it didn’t at first become a part of any new context in which it could help give definition or meaning to any other ideas. […] That’s how we started with this idea of experimenting something agricultural. It was all on really a very small scale, a few fruit trees, a little salad. […] But at the time, all in all, I was still a very political sort of person, I’d been making films that I thought of as fundamentally political in their meanings, the paintings too were still full of political allusions, the facts they contained, their titles even, and so when Agricola Cornelia first began, it began in terms that were derived from these. It too had the pretense, the aspiration, for a while, of being a fundamentally political sort of gesture. It was through politics that I’d first made a formulation of an idea of a trans-aesthetic dimension to art, it was in terms of politics and political consciousness that I’d first begun to conceive of art as exemplary moral discourse. […] It was also a question of farming it from a very particular point of view. I was interested in the idea that farming this land could also be considered a work of art. Even the produce was a work of art. Farming this land was supposed, for me, to be a way in which it was finally possible to see the full political significance of a work of art. Agricola Cornelia became my way of responding to land art, it was an instrument of polemic with respect to land art, a way of openly expressing the sense of unease that I felt about land art, a way of calling its bluff and highlighting its confusions and its lack of any real understanding of the world we live in, its lack of any real understanding of the symbols it deals with. The disturbing thing about land art is that it’s so aesthetic, and all on such a terribly wrong scale. Anything that big should have other kinds of meanings altogether. Anything that enormous doesn’t make sense any more if it’s entirely without awareness of the social realities inside of which and all around which it operates. And why is it that working with the earth can be art only if it’s that way of working with the earth? Sure, growing potatoes may not be a very eloquent kind of protest, but that’s part of what I became involved with too. I’d been saying for years that I paint little spaces because there are no more big spaces available, no more possible commissions for possible Sistine chapels, and here suddenly were all of these people who simply hadn’t noticed and who were beginning to work with bulldozers and construction companies and absolutely incredible amounts of capital, practically pretending that all of this new American wealth was a part of a society going through some sort of new Renaissance. Bulldozers, miles of trenches, trees wrapped in plastic, curtains across canyons, monumental walls and fences, kilometers of solid bronze tube and no real sense to it. […]

Agricola Cornelia. Quod a fortiori non licet, 1978. Courtesy Fondazione Baruchello

Agricola Cornelia. Quid sit opinio probabilis, 1978. Courtesy Fondazione Baruchello

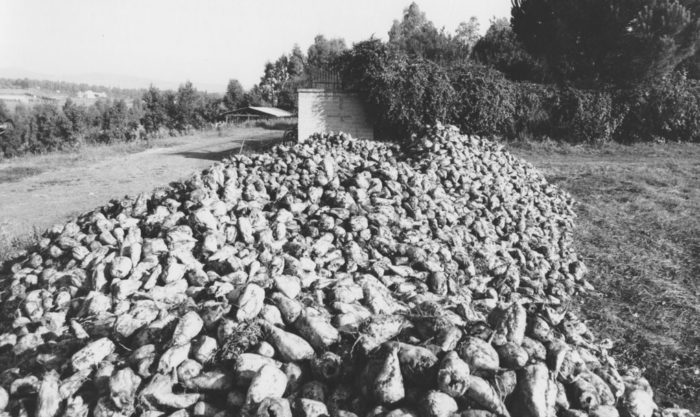

The polemic then was simply a question of deciding that the growing of potatoes is a work of art, of potatoes or sugar beets or corn or yearling sheep. Of growing them and then of giving them away, no, not even that. Rather of growing them and then of selling them. That seemed an important innovation at a certain point. There have been any number of marginal art operations in the history of the art of the twentieth century, gestures, happenings, theater, events, somebody once sold ten thousand square centimeters of earth along the Swiss border, I myself once set up a prison for words, there have been any number of marginal and experimental activities among the artists of this century, but it seemed to me that they were only accepted as art by the artists and by everybody else as well when they were content to stay inside of the precincts of the market of art. They were art if they were a part of the selling of objects or of paintings or of souvenirs or even of the artist as a kind of actor paid by the hour, a kind of glorified acrobat, a kind of glorified clown. It seemed to me that art should be able to go beyond that, that art could be a part of other kinds of commercial activities, commercial activities really concerned with the satisfaction of needs, with concrete needs rather than diaphanous snobbish social needs, needs I mean like potatoes are needs, what you do with potatoes is to eat them. […] It was a question of pulling aesthetics into economy and of pulling the most rudimentary and fundamental forms of agricultural economy into aesthetics, and so much the better then if I was doing it with produce that carne from lands that didn’t even belong to me. […] It was a real provocation. And talking about the art event of planting ten pounds of seed in a field and then making a harvest of eighty-six tons of sugar beets is hardly any less scandalous than sending a urinal to an exhibition. […] There was a point at which I even prepared a proclamation, I even went so far as to call it ‘Agricola Anti-Establishment’, it was a text to be circulated among intellectuals and art world people, mimeographed, and it described our beet operation. It was a kind of press release and it had a very polemical tone about it as far as the intellectuals were concerned, it was polemical since it considered them the middle-men in the exercise of a certain kind of political and cultural power and it invited them to give themselves over instead to creative activities similar or analogous to what we were doing here at Agricola Cornelia, to things like the practical production of sugar beets, and it quoted Foucault where he says that the plight of the intellectual is found in his duty to struggle against the forms of power of which he is at one and the same time both object and instrument. […]

Agricola Cornelia S.p.A. Beets harvest, 1976, photo documentation. Courtesy Fondazione Baruchello

This idea of Agricola Cornelia as a kind of pseudo-political, pseudo-artistic happening always seems attractive since it at least has the virtue of a kind of concreteness about it, and everything Agricola Cornelia has been about since I abandoned that original idea, or rather when I abandon that original idea, well, it becomes incredibly subtle, almost really too subtle to hold onto at all. Everybody always has the right to ask me what’s the difference between what I’m doing here and what’s going on at the farm just across the road, and it’s difficult to give an answer, it’s entirely a question of levels of consciousness, or rather of ways of looking at things. Somehow or another it’s almost a question of my having been able to find a dimension of transcendence in things where transcendence is no longer frequently found, not because it’s no longer there, but rather because nobody bothers to look for it. Talking about Agricola Cornelia seems to become a question not of what I’ve done but rather of how I’ve done it. It’s a meditation on the modes of an activity, and that’s a difficult thing to talk about, the discourse slips away into almost entirely intangible subtleties. I’ve been involved with Agricola Cornelia for eight years now, and that means eight years of trying to figure it out, eight years of notes and attempts at writing texts- there’s a whole packing case of the stuff by now – and every time I do it, all end up with is a kind of fledgling poem in prose. […] And if this isn’t aesthetics, what else could it possibly be? We’ve been involved in producing all of these living things, we’ve been growing plants and raising animals, and this food is something that’s been the subject of a great deal of meditation, even meditations on trucks full of sugar beets as they go out the gate. […] If Agricola Cornelia ever becomes an object or a series of objects to be seen within the confines of a room, I’d like that film to be projected onto the walls of that room, maybe even onto the ceiling and the floor. It was a kind of meditation. I had to move in fact into a whole period of meditation and reflection, a period in which I had to rediscover certain capacities and certain intensities, certain intelligences that find their source as well as their explication in my painting. It was only with the use of these really fundamental concepts that I was able for example to go back to film again, to decide that film was an instrument that hadn’t been exhausted for me as a result of its having been used as a means of political involvement. […]

Agricola Cornelia S.p.A. Beets harvest, 1976, photo documentation. Courtesy Fondazione Baruchello

It wasn’t until then that I began to ask myself questions like, ‘What’s a cave?’ or ‘What’s the life of a man in a cave? What’s the nature of our relationship with the ground, with the earth, with dirt? What was the meaning of the discovery of agriculture? What’s a forest, a jungle? What’s grass? And why do animals feed themselves on grass? These enormous quantities of grass that they eat. These beasts with their mouths always full of grass, these enormous quantities of grass that they’re constantly turning into equally enormous piles of dung. Dung that’s used to restore and fertilize the ground and make the grass grow back again. This whole mysterious nitrogen cycle. That’s all extraordinarily curious, this hunger that an animal has, this brute hunger that’s almost like a madness, an obsession. A cow gets up in the morning and in the course of the day it goes through two hundred pounds of grass that it I feeds into that enormous belly that it has. There are these cows out in the field now, they’ve been there all day, and they lie about and they go from one place to another and they never stop eating and then in the evening they come back to the stable and there’s the hay there and they launch themselves onto that as though they’d been going hungry, as though they’d been deprived of food and had had nothing to eat all day long. The way they butt each other, the cows attacking each other and the bull too, all just to get to this hay. And then when they’re about to go to sleep they regurgitate it up and keep on chewing on it more, and part of it’s transformed into dung and the rest is transformed into animal protein. And it’s the same thing all over again with the sheep. We had a herd of two hundred and twenty sheep and you let them out into a meadow and in the space of just a couple of days it’s cut absolutely clean, literally devoured. And all of this gigantic voracity is finally transformed […]. The thinking that leads me now through the experience of Agricola Cornelia is in fact an extension of an idea of testing the power of art against the power of the much more potent structures that stand adjacent to it. That’s an idea that comes from a long way back for me. I’ve done things in imitation of industry, advertising, and finance, for example I once did a “one man billboard”, and I also did a series of banking events, in a gallery, things like selling ten lire coins for fine lire and five lire coins for ten lire, and even though things like this may not mean very much, they will still important for me. And with Agricola Cornelia, I’ve gone on to something more radical. From simply imitating the structures of social thought and action—the structures for the agricultural production of food-stuffs in this particular case—I’ve progressed to asking myself what would happen if I actually tried to replace them.