Fandom’s Counter-reality

Glitch of intimacies in Shuang Li’s “Forever” at Peres Projects, Milan

Starting with a heart-shaped fountain, where concerts fragments of My Chemical Romance and erupting volcanoes youtube-found-snapshots are projected, Forever by Shuang Li opens up multilayered questions on today’s fandom, technological interfaces and intimacy.

Shuang Li is a transdisciplinary artist interested in questions around embodiment, displacement and technological interfaces. In her practice, she explores ever-changing experiences of intimacy; with an emphasis on the emotional impacts of Internet platforms and digital screens on our bodies.

After meeting the guitarist of My Chemical Romance, Frank Iero, Li started to dig into her life-long experiences of fandom, and its idiosyncratic gender politics which increasingly became a prominent matter in her practice. Born in the 90s in Wuyi Mountains, and more recently living between New York, Berlin and China, Shuang Li defines her encounter with American punk-emo band My Chemical Romance as a teenage life-changing moment. Growing up in an isolated industrial town of southeastern China, the band’s lyrics resonate with her desire to escape her own body and surroundings.

The installation Heart is a Broken Record (2023) performs a concert that never took place, a montage of concert clips that crystallizes the euphoria of fangirls before seeing their stars. By showing only the galvanizing suspension of the prelude of concerts, and leaving the encounter open to the imagination, it creates a tension similar to fangirls’ fantasies and deferred pleasures in the viewers. The glitching fountain becomes a tribute to the oceanic feeling of being one with lovers’ bodies, and the altered states of dissolving into dancing crowds, a tribute to the sense of belonging of fandom, simultaneously reclaiming amateur, fan-fiction as a production mode. A quintessential adolescent feeling, fandom has historically been marginalized in popular culture as juvenile, often femme, and immature inclination. Yet, as Shuang Li exhibition exemplifies, there has been an embrace of fandom in contemporary art discourses and feminist practices. Thus, in an increasingly technology-mediated society, can fandom represent a personal and collective re-orientation and negotiation of our shared realities ?

It’s interesting to emphasize how from a sociological point of view, fandom transcends traditional understanding and limitations of personal identity, bringing into being unprecedented communities crossing generations and spatial divisions. In the patriarchal, consumer-oriented societies we are living in, fandom offers a conceptual framework to engage freely into an emotional, hyper-feminine behavior that otherwise would be restricted and silenced. It represents a pretext to subvert the disciplining of the body imposed on womxn and queer people, and indulge in socially unacceptable manners, while manifesting publicly emotions commonly considered as “negative” such as obsession and envy. Disrupting established norms and perceptions, fangirls’ heterotopia gives subjects a chance to know themselves in more nuanced ways, deeply affecting their physical selves and realities. In fact, despite late-capitalist consumerism’s attempts to incorporate and commodify its radical potential, fandom still represents a transformative experience that challenges the prescriptive modes of sociality and intimacy within neoliberal society.

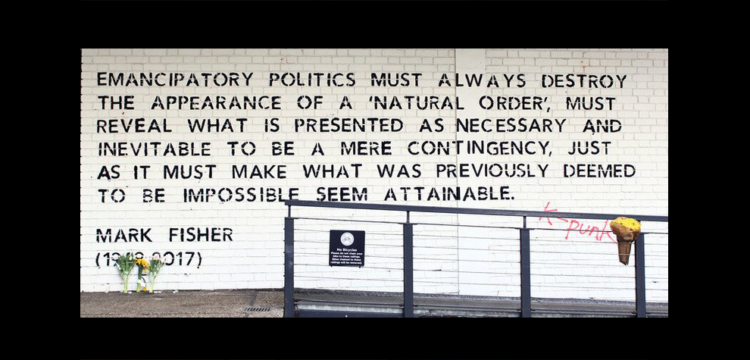

Fandom is “is the only kind of ‘love’ that has real philosophical implications, the passion capable of shaking us out of sensus communis.”

But most of all, as Grant and Random Love argue in their Fandom as Methodology: “for girls, fandom offers a way not only to sublimate romantic and sexual yearnings but to carve out subversive versions of sexuality.” The Internet and fandom foster alternative ways to express and experience sexuality beyond the capitalist heteronormative regulations based on social reproduction. Almost dematerialising desire and sexuality into atmospheric forces that pervade everything, Internet fan-fiction arguably expands the vision of what love might look like. Fangirls’ fantasy and identity experimentalism allows marginalized communities to find glitches of intimacy and pleasure, not limited to sexual heteronormative intercourses, dismantling the binary logics of phallogocentrism. As Fisher claims in his K-Punk blogs, his commentary on underground music, politics and digital cultures, that can be considered a act of fandom in itself, fandom is “is the only kind of ‘love’ that has real philosophical implications, the passion capable of shaking us out of sensus communis.” By fostering an alternative set of values and self-composed-realities and connecting different people across geographies, generations and communities, fangirls bring into being an alternative conception of “affects” and “love” completely opposed to the neoliberal commodification of online interactions. A counter-reality that arguably operates a shift of meaning of love, from an action aimed at beloved ones to the subject itself.

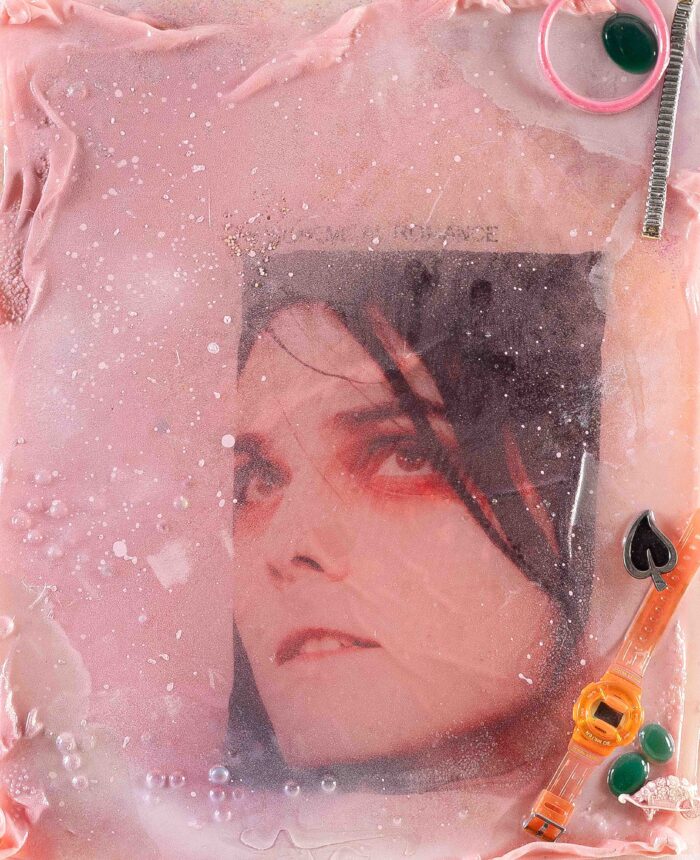

In a similar way, the exhibition Forever creates an intimate and nostalgic space; entering the exhibition at Peres Projects in Milan, visitors have the feeling of stepping into someone’s room, or getting glimpses of someone through a recollection of their I-phone gallery or Instagram feed. It’s interesting to analyze how fandom is both, a topic present in Shuang Li’s works and simultaneously a methodology entailed by the artist. In fact, the multimedia installations, spanning from sculptures, casts resin paintings, and performance documentation present a mode of association, rhizomatic assemblage and autofiction that deeply resonate with fangirls’ strategies.

Like a time-capsule just undiscovered, Li’s personal archive embodies the eternal resurgence of y2k fashion trends, embracing kaleidoscopic elements of bimbocore, kawaii, and punk-emo aesthetic thriving on platforms like TikTok. Blurring mundane objects into the artworks, handwritten notes to her teenage-idols and posters overlap velveteen fabrics, translucent beads and girly nostalgic objects such as CD-portable-player adorned with glossy pink devilish writing bearing the word “innocent”. The punk-emo leitmotiv charges the redundant cuteness of these objects with a grotesque, uncanny aura. Also the textile components within Li’s works such as The Portrait of the Artist as a Young man and All the Letters I Ever Written (2023) emphasise a tension between virtual and material reality, infusing substance to digital aesthetic and dis-embodied imaginary so pervasive in our online experiences. Shuang Li’s fandom methodology elevates seemingly trivial gadgets and charms doomed to oblivion—often lost or overlooked in the deluge of digital production—into cherished objects of affection.

Fandom and technologies of romance represent core underpinnings also in Lord of the Flies (2022) performance documentation. Constrained by Europe’s Covid-19 border closures, on occasion of her opening at Antenna Space, Shuang Li delegated twenty performers dressed with My Chemical Romance t-shirts—mirroring her personal style—to search for her friends in the Shanghai crowd. Each fangirl then proceeded to read a personal letter written by the artist to these friends on her behalf, capturing their reactions through spy glasses with embedded cameras. Starting from her personal experience of displacement, Lord of the Flies, reflects on the virtual bodies and glitch of intimacy facilitated by online interactions while contemplating their inherent immateriality. Thus, every avatar, every alter-ego that multiplies and poetically doubles the body of Shuang Li simultaneously signifies her material absence. Quoting the artist, the performers’ love letters, resembling the intermittence of TikTok dances, act “like glitches implanted in reality”, demonstrating how the affective aspects of digital screens erupts into irl.

In the multimedia documentation presented at Peres Project, 3D model platform-boots and concrete-casted distorted legs-warmers constellate the exhibition space, becoming tangible vessels of the absence of performers, and, per extensions of fan-idols. In fact, it is precisely the absence of stars’ bodies, objects of affections, that creates a conceptual space for identification, personal expression and desire in constant becoming. Yet which futures are mobilized by indulging in fangirls fantasy and alter-egos? What are the implications on embodiment, construction of identity and desire away-from-keyboard?

Shuang Li’s approach to fandom as a methodology unveils a gesture of attachment and care, an ode to fangirls fantasy and pleasures. Whether emo-idols or oversea friends, fandom becomes a medium to reach someone and mobilize alternative realities.

At the threshold of virtual and material realities, Forever‘s assemblage of objects and media become a metaphor of our online manifestations fracturing the idea of solid stable subjectivity and redefining interdependency within communities. Fangirls’ experimentalism and collective negotiations initiate a process of self-discovery and autofiction that has tangible, long term effects on the world. In this light, Fangirls foster an alternative mode of signification and set of values, not based on the logic of production, but instead on affects, peer-networks and care, eventually re-enchanting the world.

In the ever-evolving landscapes of digital intimacy, fandom becomes a galvanizing momentum from where unprecedented communities and visions of the world can emerge, a prefiguration of alternative realities and post-capitalist-desire.