Familiar Noises

On Alice Visentin’s “Cieli Neri”

J’habite ma propre maison,

n’ai jamais imité personne…

—Hélène Cixous

Why is imagination so important and why is it not so difficult?

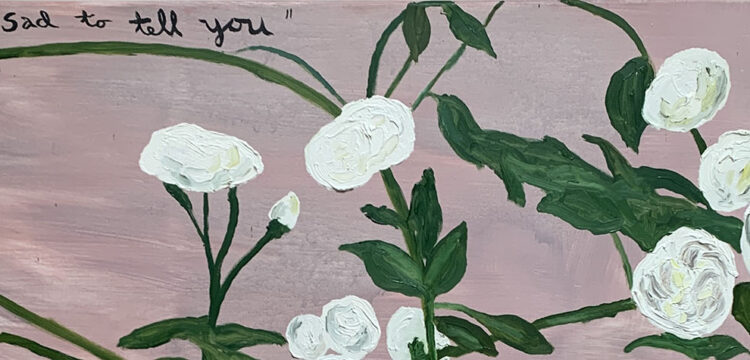

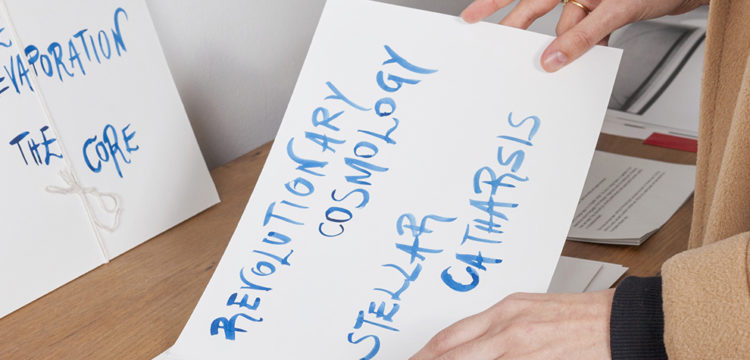

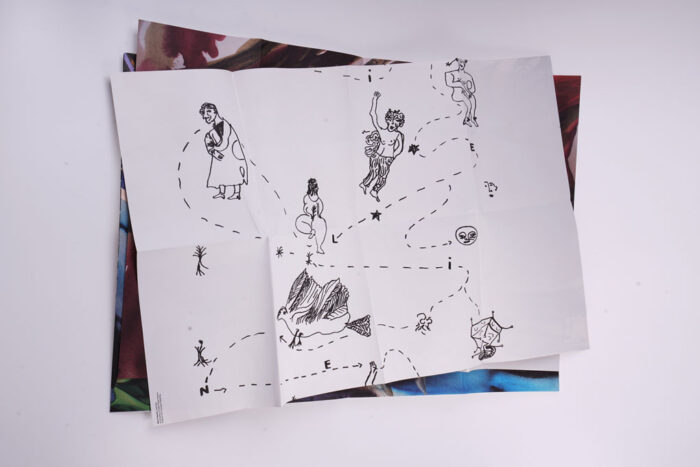

Apparently, in such a time of urgency like the one we are currently experiencing, science needs imagination. On the other hand, art faces an imagery that overturns and traces both disciplinary and scientific systems of order, classification and control. In between the obsession for knowledge, and a kind of understanding without end nor finality (some sort of hubris), there are those who are concerned with looking beyond the dark side of this artifici(al)ous illumination. There are those who prefer poetics of landscape over territories, those who raise their eyes toward the rigor of a multiple and stratified relationship, and those who do not comply to weak universal conventions. Alice Visentin’s paintings are inscribed in this framework, in a place of memory that is not bounded to those shadows of the night which vibrate of pre-existing contours, distant echoes and familiar noises, wandering through proximity in the oral word. Finally, the house renounces its walls to return to its origin. The transparency of the space allows to glimpse at the opacity of all the relationships and their connections, at the inscriptions and the filiations, at the rhizomes and their germinations. The figures in this painting are a game of memory and place, which inscribes the experience in the poetics of a relationship—in a sacredness beyond history. Visentin signs a manifesto with water. It does not look like her name, but like a stream of experiences and traces belonging to the cosmos, organized in large-scale drawings, by watercolor and wax crayons. Water is the glue of the subjective experience, of the elements, of the observed rivers. The colors stand out on a long paper poster: an agglomeration of reversal and intrusion, of ruptures and connections. Silhouettes and masks—stylized and caricatured characters follow the grotesque articulations of a recalculation: a reversed astrology, no longer in the sky, but on earth.

How to infect architecture with its exterior? How to transform architecture into becoming?

In Alice Visentin’s painting there is always a passage. Passages become permeable and edges become boundaries to be crossed. Although frontal and almost hierarchical, figures are never completely static, yet again on the verge of identifying themselves with a limit to be transgressed, with a color, or a word to be swallowed. The vernacular and popular culture and the oral stories nourishing this painting are not static elements of a disciplinary grammar, but rather movements of interiority, of domesticity, ready to derail with chaos in order to reorder. Interior and exterior cohabit in a patchwork of cuttings, recompositions, remixing. A junction for forgotten stories, to be found in a symbiotic and syncretic way. Alliances with other species are founded, more stories along other creatures. The word can renew itself. There are no limitations over these organisms’ conditions of existence. We want to get out of the house to infect the outside with the inside. The painted paper poster is a papyrus from the future recalling the mists of time, all the places where humanity lived for centuries, the sudden ecological desolation of the last century and then, again, the abandonment of every dwelling. “This passion of wandering predicts the poetics of the relationship” among all the creatures and temporalities.

Sonia D’Alto: For the exhibition Cieli Neri, you started from wild black skies, unlit by electricity. You envisioned a house first lived and then abandoned by humanity. Is this genealogy linked to a possible relationship between your painting and the open space? I think of a sort of en plein air painting that unconsciously expresses your desire to get out of the enclosed space of the studio, so to open up to unexpected encounters.

Alice Visentin: The first image that comes to mind when talking about open space is a flat meadow, divided from other meadows by small canals. Here and there, small houses containing farming tools. The open space is for me a site of archaeology. It is the place that makes me wish I had Aladdin’s lamp in my hands to see all the treasures of the Earth at once—and perhaps the whole history at once. Since we don’t have this lamp yet, I imagine and paint.

What is the relationship between your work and architecture? And, in this case, between your work and Toast Project space?

The great thing about Toast is that it doesn’t have a specific facade. I was told that it was the guardhouse of the concierges, and from there you have 180 degrees of visibility. I wanted the arrangement of volumes inside to follow some law of balance, as if it were a large display case. Like a river, the paper found the right balance to bend and reveal itself. The paper adapts and looks natural in its behavior. It happens both on an architectural level and on that of the pictorial surface. It is a medium that lends itself to improvisation. It does—almost—whatever it wants.

When you paint, you often incorporate multiple voices: fleeting and insubordinate witnesses of senile creatures, rural communities, local traditions you summon in congresses, assemblies, bands: like encounters on and beyond the canvas. This stream also gathers often oral words which become paint, color and water. How did you approach this imagery and this repertoire of experiences? Is it an interest in a subaltern matrix— “the culture of a people that has long remained subaltern to a dominant culture”?

This imagery simply comes from my life as a child until I moved to the city. I used to spend a lot of time with my grandparents in the mountains. The social rules there were different than in the city. There was the village band, the torchlight processions, the old ladies scattered in the woods at night, the stories and songs around the table in the evening. But also little groups of kids in the main square, and this memory still fascinates me.

Surrounded by magical stories and songs, by bands and torchlight processions, people’s lives seemed more aware, the fear of human existence was exercised and life was much easier to deal with. I began to unfold the idea that the imagination brought by songs and stories is an atavistic space of freedom and of mutual recognition within a community. Orally transmitted culture is a space that hasn’t been censored much, perhaps because it is immaterial—although very tangible “inside” every subjectivity.