Empty Cities

A quarantine dialogue and some thoughts on the present around George Drivas’ filmic work

In a time of quarantine where the whole planet was in a lockdown due to the threat of Covid-19, the images we had seen on the internet of the empty cities, the emotions we experienced and the thoughts we had on issues that came to the fore, had brought to my mind the filmic work of the artist George Drivas. Alienation, lack of communication, anxiety, silence and the eerie places that are often captured in his lens, invited me to rethink his work through what we were living in this historic moment for humanity. Through his work, we can reconsider issues concerning the society of surveillance, the loneliness of big-city life, the effort to communicate in our contemporary world, the economic and environmental crisis, and even the weakness and difficulty of love. Thus, during the days of the first confinement of March-April 2020, I asked George Drivas to discuss diverse burning issues that his work raises. Today, a year after the first unprecedented lockdown in spring 2020, we are again facing the same questions after having lived together with this pandemic for a whole year.

Daphne Vitali: Your works could take place in past or future times and in different cities of the Western world. They carry the loneliness that one may experience in a big city, a concern and anxiety for the future, the effort for self-determination, existential allegories and convey a sense of dystopia and futurism, deprived of a significant human presence. First of all, I would like to ask you how these works came about. What did you have in mind when you were creating them?

George Drivas: These works of mine that you mention have been originally conceived in various big cities that I have been living for long periods of my life. I wanted them to express the feeling of my own lonely walks, my own silent explorations or maybe my own dialogue with the bare or unfamiliar urban landscape. They arose from the question of how large a city would be if it were completely empty, how would it be if suddenly the urban landscape was deserted. What would a city be without any humans? What would a human be in an empty city? I was not interested in the reasons why such a thing could or could not happen. I was intrigued by the sense that would emerge through such a hypothetical scenario, namely the possible sudden appearance of an endless urban void and absolute loneliness as a mandatory unique human condition.

Consequently, as one of my heroes says in one of my last works from fall 2019, I was interested in a situation “when nobody will be so sure of one’s self, when everyone is in need, when everyone is a stranger, when everyone needs help.’’ Unfortunately, a few months later, these words were our daily life, our new reality.

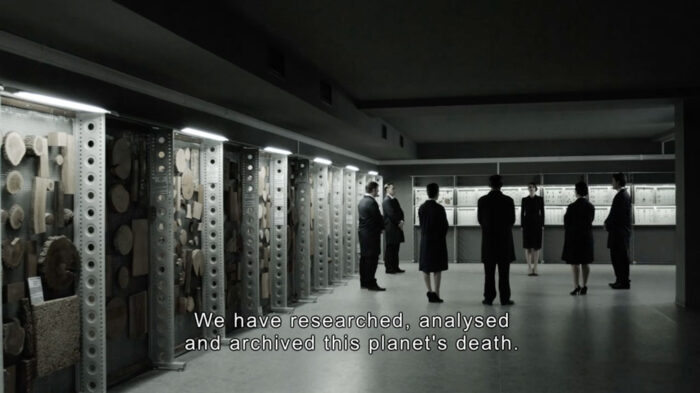

In your work, you often present your characters in conditions of control and observation. Your few and often anonymous heroes move in public places and buildings, while giving the impression that they are being watched as their movements are recorded. Your work Beta Test, which is also the first part of a trilogy entitled Social Software, deals with the history of a city where surveillance, lack of communication and a sense of non-existence prevail. The characters do not seem to live in real life, but follow the control instructions they are given, in a laboratory-like condition.

One of the most important legacies of the pandemic we live in will be the way in which this pandemic is combined with the rise and spread of digital surveillance activated by artificial intelligence. China, as we have seen, has used multiple surveillance tools to deal with the coronavirus. These techniques ranged from developing and using hundreds of thousands of CCTVs to recording people’s movements, to mass-monitoring mobile phone data, to face-recognition cameras, to body temperature controls and reports, to credit card tracking movements etc. Several Western countries have begun to turn to similar methods of monitoring citizens. Nevertheless, it is accepted by most that democratic governments should offer an alternative to these authoritarian and totalitarian processes.

In your work you present a condition in which the system is controlled, but at the same time this system seems to control us. In other words, a software has been created to monitor society, but in the end, it seems that we control ourselves. Tell me about the idea of surveillance in your work, but also about your predictions for the future of surveillance society. Can the West benefit from the surveillance methods activated by artificial intelligence without sacrificing fundamental freedoms?

I would say, after reading the first paragraph of your question, that you do not only describe an old work of mine, but at the same time the current situation in the entire world. Public space is becoming a field of control. Coexistence is marked in the collective unconscious as antisocial behaviour that increases the likelihood of the virus spreading. Socializing tends to be considered dangerous. The city, this human construction, loses its primary function, the primary reason for its existence. Instead of mass meetings, personal transactions and communication, we experience the exact opposite, their absolute denial and an absolute ban on them. In a sense, cities today are the field of a new experiment, a new form of operation that is the exact opposite of their previous one. If mass coexistence was something that was tested in global cities before the pandemic, now, what is being tested is a kind of mass isolation. What will be the city of the 21st century? The testing ground of a completely new era of alienation and a completely new—permanently supervised and controlled—way of life? The absolute obedience of citizens to strict orders and consequently their supervision is not the only way to deal with the coronavirus; or perhaps it unfortunately is, but only when all other ways have been tried and failed.

The system you mention and which is always present in my work is our very own selves, the world we have created, the laws, the societies we live in, or just our bodies. They are all producers and agents of power. Perpetrators and victims. I am therefore primarily interested in all these systems that, while created and partially controlled by us, at the same time make our inevitable limits visible. We operate universally and inescapably on the basis of a number of certain factors, that it becomes almost impossible to understand whether we are really the ones who create these factors or they are the ones who “autonomously” create us. Among these factors is technology. How much do we control the machines we create? How much can they control us? How much do we look like them and how much do they look like us? If we create surveillance machines, it is because we believe and invest in a regime of constant surveillance, just as when we create production machines we invest in a regime of constant production: It is the way we perceive the world around us and consequently ourselves, and at the same time it is the way we have learned, chosen, forced to exist. We are producers and products; we are supervisors and supervised. How we will manage to escape from these conditions, to change them and move forward, is a question that every generation is called to face. The way we perceive this balance is in essence the way in which humanity perceives itself, the way each time we create our history.

I would like to talk about concepts such as pause, silence, stasis and waiting; conditions that we are experiencing these days more or less all over the world. The images recorded by drones and what we see these days on the internet, of empty cities, forgotten squares and boulevards as well as the ancient ruins that stand imposingly in a city where life goes on without humanity, are images that we truly encounter in our lives for the first time. Nevertheless, in the cinema, we may have seen them before.

Film theorists Laura Mulvey and Raymond Bellour have pointed out that stillness and slowness provide room for reasoning and thought. The importance of pausing is very important in your work and specifically in the way you compose your films, often starting with a decomposition of the moving image. In your early black-and-white works, you use still frames instead of continuous motion, based on the aesthetics of still photography. However, this stillness seems to be not only a form of image processing, but also a study around the idea of pausing. Cities, in your works, seem to have stopped in time, people to have disappeared or hidden themselves, and the present to have been suspended. This stasis and the limbo we experience today reminds me of your cinematic silence. Can this waiting time be fruitful and dense in meaning? How can we make the suspension of time useful and valuable?

Of course, I am in favour of pause and/or silence as a necessary condition. What if we stopped talking or moving for a while? To produce or consume? What thoughts would we have then? What would we consider important and what would be insignificant? But what exactly pause and silence mean for everyone, is a broader and not entirely clear topic. I have the feeling that we are living in a constant state of acceleration, a constant pressure to produce and consume everything, an unstoppable momentum without a clear goal. But, this does not apply to the whole world in the same way. For some people, restlessness manifests a desire for excitement and interest against an otherwise boring life; for others, it is their sole condition for survival. So, respectively, the pause, the halting of time imposed due to the pandemic, may be a fruitful time of recollection and reflection, but it can also be a tragic catastrophic interruption. The quarantine is not always and for everyone an opportunity to stay home more than usual, but also a torturous confinement in inhumane living conditions.

Today, human contact is a huge threat to life. Love, the preeminent form of contact between people, has essentially ceased to exist in practice—at least among people who do not live together. Although love is a key vehicle for survival in a crisis, in these times, where we witness the rapid spread of the coronavirus, the idea of sexual intercourse is not only worrying but also life threatening. Of course, pointing out that there is a relationship between love and death is not new. As we know, death is the opposite pole of love. Love is interwoven with the instinct of self-preservation, while death with loss. As the French philosopher and sociologist Edgar Morin recently put it, “in human history, the two incompatible but inseparable enemies of Eros and Death will continue to fight, and Death will not be able to destroy Love, but neither should Eros eliminate Death. Everyone in turn will have the upper hand. Today the strongest are War and Death, but there is no eternity in history.”

Your works often convey a certain impotence of love, the sense of a love that may not exist anywhere, a sense of loss and loneliness stemming from a separation that, in your filmic work, is caused by unknown factors. Tell me about the idea of love in your work, but also in relation to the current situation, that is, in a moment of extreme isolation.

In my works, as you say, people often meet and separate. They look at each other but don’t talk. They are trapped in their thoughts, goals, commands, obligations. Doesn’t this bear a close resemblance to the reality we experience in our daily lives? Random encounters leading nowhere, communication difficulties, an inability to coexist. I don’t think I describe anything more than what happens to us everyday. And yet in this rabit-hole of non-encounters, we may experience the happiness of a moment, a pleasant gesture that certainly acquires an almost existential significance, without always being sure of the reasons why this happens. We are desperate and at the same time so lost that, on the one hand, we are looking for something and, on the other hand, we are not able to accept it, let alone enjoy it, even if it is offered to us. Even in that ultimate moment of a “chance encounter” we’ll look at each other with the usual suspicion and insecurity that characterizes us and we will probably be (self-)rejected. All these do not interest me as personal, sometimes romantic petty dramas, but as a complete sense of emptiness and absence. Like an all-embracing sense of an inevitable loneliness that cannot but end up becoming the main characteristic of my heroes—and, as such, I treat it as a central and essential problem of a global society and, of course, of an entire era. A “profile” that we carefully created on social media and are afraid to try in vivo, is now becoming our only face. Very often, virtual meetings are no longer the first stage of an acquaintance but the only stage. We survive through the complete cancellation of our body, of our own physical existence. Consequently, when our body is allowed to circulate freely, then it is required to wear a protective, medical mask, that is, a facial removal, a depersonalization. We exist as persons without a body in our electronic communication or as bodies without a face in our physical coexistence. So we are at a point now, where we claim the right to self-determine our entire body, the last stronghold of privacy. In times of pandemic, standing close to someone, let alone hugging and kissing in public, can be a provocative action, an existential cry, an almost revolutionary act.

Your work Empirical Data is a film that deals with a person’s relationship with a “foreign” and often hostile environment. This is pursued through a character who, while trying to establish himself socially, seems to be changing in order to be accepted by the system, by this new environment. Your works often speak of the individual’s position towards a system, while your heroes are presented cut off from this system, from their environment. The system could be an unknown mechanism or an unspecified social whole. Today we are, as individuals, as units facing a system, isolated and disconnected from each other, feeling alienated and disoriented in a simultaneously familiar but also hostile environment. What is this system you are dealing with?

The system is the world we have co-created and which inevitably includes but also excludes us. Without, of course, each of us having exactly the same share of influence, we are both perpetrators and victims. We create a system that creates us. Even pandemics are not an unpredictable natural phenomenon. They have specific causes that go back to economic and social aspects of our time, aspects that we created ourselves. It is, in a way, the result of humanity’s choices, although—I repeat—not everyone has the same degree of responsibility. Whether we can realize it and oppose it is a rather philosophical-existential question. It would be like wondering if we can oppose ourselves, if we can change ourselves radically and set completely new goals, have completely different dreams for us and the societies in which we live. Can we do it?

Your entire filmic work is about managing a system’s crisis, miscalculation and error. Operational difficulties in the Social Software trilogy become a state of emergencies in your most recent projects, and the concept of crisis is beginning to take the form of socio-political problems. “The system is on the verge of collapse” says the narrator in your film Sequence Error and is called upon to lay off workers. A strong socio-political work, which deals with issues related to the crisis that Greece has recently experienced, but through which we can also reflect on the social repercussions that the coronavirus crisis will have.

Today, everyone is talking about the Covid-19 pandemic as the biggest crisis in the world since World War II, and this is perhaps the first time we have seen so clearly our interdependence in a globalized world. Even if some countries manage to slow the spread of the virus, Covid-19 could return if the pandemic remains severe enough elsewhere. As Bill Gates recently argued, “In this pandemic we are all connected.” What can we learn from such crises and emergencies? How or in what ways do you use the concept of crisis in your work?

Crisis is the moment when we realize that we are not invulnerable. It is the moment when our confidence is negated and our feeling of security collapses. Crisis is the moment when the ground is lost under our feet and we can no longer be sure of anything. Crisis is to experience what we considered unlikely to happen to us. Of course, such phenomena have many applications and interpretations, while they also operate on many levels, personal and social. A crisis does not affect everyone in the same way. The fact that the world is becoming more and more united, so that we can no longer be indifferent to a virus in China, a war in Syria or the collapse of a bank in the United States, because we are all connected, does not mean that we are equally exposed.

The global economic crisis, the refugee crisis or the pandemic are not affecting everyone in the same way. The pandemic is a symmetrical threat, but of course—and as always in similar cases—it has quite asymmetrical consequences. We do not all experience in the same way the fear of death, the lack of medical care, exclusion, loneliness or financial hardship. A phenomenon that, for some people, is a nightmare, for others is just an interesting self-reflecting experience, while for others it may even be an opportunity for financial speculation. In that sense, the economic crisis, due to the pandemic, is affecting everyone but not in the same way. Can we agree that we should all be concerned with managing this issue for the social and working classes that are most affected? If every global, social, financial tragedy is experienced as just a problem of “others” and not as an absolutely common problem, then I am afraid that at some point it will literally affect all of us to the fullest extent and maybe then it will be too late to do anything.

In 2014, you were invited by Polyeco, a Greek, toxic waste management company to attend a project it undertook in collaboration with the United Nations, which was related to the cleaning of toxic waste from Tbilisi, in order to create a new film work. Thus, you stayed in Georgia for some time and created Kepler, a work that deals with the issue of toxic hazard in our contemporary world through the controversial same-named construction project, as narrated in the film. One would say that in this work you are talking about destruction, but at the same time about hope and a new perspective.

The destruction of the environment has been directly linked to the Covid-19 pandemic. According to microbiologist and professor Philippe Sansonetti, Covid-19 is a “disease of the Anthropocene”, an overall phenomenon in which the biological reality of the virus is now inseparable from the social and systemic conditions that cause its existence and its dissemination. Moreover, as Bruno Latour has pointed out years ago, in his book We Have Never Been Modern (1993), we must reconsider the way we perceive modern politics, emphasizing that we must not think of our political order as clearly distinct from nature. Instead, he suggests that the political order is always interwoven with the natural. It is clear that environmental factors affect society significantly. The Covid-19 pandemic forces us to think that it is time to tackle the fact that our own political system has played an important role in the production of this new ecological factor, Covid-19. In a global economy that is increasingly intervening in the ecosystem, it is not surprising that new viruses appearing in one place can migrate to the other side of the world at lightning speed. Is the crisis that we are currently experiencing an opportunity to reconsider these distinctions and rethink the definition and constitution of modernity itself, as Latour suggests? Can we correct our mistakes, think about the world differently, make a different restart and pay attention to the biosphere on which we live and act? How do you approach current environmental issues in your film Kepler?

Kepler talks about a catastrophe that can happen very close to us very easily. Can we do something to avoid it? And this, of course, does not mean to care only for what is next to us, but on the contrary, as I said before, to realize that if we do not care in general about what is happening elsewhere on the planet, then this will happen very quickly next to us and maybe then might be too late to react. Are we ready to accept the necessary (economic) price of a change in the production process in order to save, for example, the environment and hence ourselves?

The growing intervention on the ecosystem combined with the unification of the world at various levels produces a new reality where one cannot be excluded from a problem no matter how hard one tries, no matter how far the problem is in the first place. The point is not that some people are not—or will be not—connected, but rather that sooner than later no one will be disconnected. And this is exactly the challenge of the 21st century. Realizing that we are all inevitably together and therefore we will not be saved by self-exclusion, entrenchment, non-acceptance of the other, by borders and walls, but on the contrary, by having a shared solidary perception of a common present and an even more common future. Kepler suggested that if we do not stop now, if we do not reconsider our future moves, then we risk not having a future at all. And this future is not about some generations to come, but it may be for us in a few years. Our future is not far away; it is already here. Are we ready to rethink our world from the beginning on a new basis?

Kepler is a planet in which climate conditions are similar to those on Earth. I wonder if humanity would continue to make the same mistakes even if it would start from scratch on a new planet. In the same way, I wonder if we will be the same after the end of the pandemic. To be precise, I don’t know what is better or worse: to stay exactly the same or to change ourselves completely and, if so, then I wonder what this change might be.

Laboratory of Dilemmas, a narrative installation based on the tragedy of Aeschylus Iketides, with which you represented Greece at the 57th Venice Biennale, confronts the viewer with a dilemma: the salvation of the Foreign or the preservation of the security of the Domestic. In your work, the dilemma takes the form of a scientific decision between the union or not of two cell populations for the needs of a biological experiment that studies the treatment of a disease. At the time of crisis, scientists have to make a decision. In this work you expose the anxiety and concern of individuals and social groups when they are called to manage and decide on an important issue. How ready are we to protect someone who is threatened when that means endangering our safety? What is scientifically correct and what is morally acceptable? The social and political concerns adressed in the ancient tragedy seem to resemble the dilemmas faced by Greece and Europe not only in regards to the immigration crisis, but mainly with the reception and the acceptance of that which “different” and “foreign” within the existing social structures.

Many of the ethical questions that this work raises can also be reconsidered today in relation to the solidarity that was or was not displayed by various governments in confronting the coronavirus pandemic. We have recently seen that while some powerful states immediately closed borders with Italy (the first country in Europe to be hit by Covid-19) without offering any help whatsoever, other smaller states such as Albania considered it important (even for symbolic reasons) to offer some help and send doctors to the neighboring country and therefore be deprived of their own medical staff. The dilemma that concerns your work on the salvation of the Foreigner against the preservation of the security of the Domestic, is a timeless question that, as we can see, becomes again relevant in the present conjuncture. An important dilemma facing humanity at the moment is that between nationalist isolation or global solidarity. Both the epidemic itself and the ensuing economic crisis are global problems that, as many have argued, can only be solved effectively with global cooperation. As the well-known Israeli writer and historian Yuval Noah Harari recently pointed out, “humanity must choose. Will we travel in the direction of division or will we adopt the path of global solidarity? If we choose separation, this will not only prolong the crisis, but may lead to even worse disasters in the future. If we choose global solidarity, it will be a victory not only against Covid-19, but also against future epidemics and crises that could challenge humanity in the 21st century.”

I strongly agree. What I believe and what the Laboratory of Dilemmas said is exactly what you suggest. At some point we have to decide on a personal, social and global level what societies we want to have, what kind of people we are. The idea of entrenchment, isolation, borders and nationalism is not only naive but also quite dangerous. And I don’t mean dangerous just at the political level because it breeds monsters, but also at the level of simple functional survival. The world is one, our planet is one, and it is in everyone’s interest that we face all problems together. A war, a dictatorship, a refugee problem, a medical challenge etc. are issues that must concern all of us. The answer is not isolation and distancing, or “whoever finds the vaccine first, wins first.” We must all work together to find out faster global solutions for the benefit of all. Solidarity and mutual aid are not just humanism; they are now elementary functional intelligence. Together, we all win.

As the French historian Jérôme Baschet recently stated in an article in Le Monde on 02.04.2020, “historians often began in the 20th century in 1914. In the same way, one day they will explain to us that the 21st began in 2020, with Covid-19 coming on stage.” It is indeed indisputable that this pandemic will change many things in the world as we knew it. The question is towards which direction are we going. How do we imagine humanity in the future? What would we like to leave behind? How to start the 21st century? What role could art play in shaping this new era?

Art, in every of its forms, keeps us awake. Art always asks the right questions, discovers and highlights subtle aspects of various social phenomena, and above all reminds us how important it is to keep envisioning something different. Art helps us to be in constant intellectual creativity. Let us also consider that art, among other things, is also a professional sector that is hit very hard these times, precisely because, to a large extent, it is based on the coexistence of people, on a collaborative form of production and participatory “consumption”. The way in which societies will support the art sector, among other sectors of production, will be a defining moment of their future. What if we stopped dreaming, what if we stopped seeing the world completely differently, what if we stopped challenging our own perceptual capacity? Art is a key towards new eras, a necessary process to find better alternatives for everything, while at the same time functions as a tool for empathy. We can’t discover anything new, we can’t create it, and we will certainly never be able to experience it if, first of all, we are not able to imagine it.

We are currently in the middle of the second lockdown in our country. Between the two enclosures, you made a new five-channel video installation titled Aeonium. In one of the monologues / confessions of your characters in this new work, one of your heroes says: “Perhaps, coming to think about it, fear is exactly what I need. Fear helps me. I make some plans. I organize my days with fear lurking over me. Fear for everything, or perhaps nothing. I wouldn’t live without fear though. It gives me structure, a reason to exist. You build on it and make plans. […] So, is being scared a synonym to surviving?”

In a moment of pandemic, fear, anxiety and insecurity are the basic emotions that our society experiences. For some, fear is something that must be overcome, in order to be able to move forward. In the case of your hero it is a driving force. Tell me about the meaning of fear and how you perceive it through this work.

I think fear may be for some people the awakening from lethargy, the waking- up, the removal of any certainty. In this sense, through fear, we redefine our existence, we rethink about what is really important. Of course, as the hero of my work suggests, fear can also mean compulsory organization, coercive discipline, or even a reduction of freedom, and this is not something that is negligible. Perhaps the question that lurks in this monologue is why we, as groups or individuals, need the pressure of fear to rediscover a meaning or a driving force in our lives, to rethink the importance of our existence and the environment that surrounds us or to protect and restart our societies.

Aeonium is about a group of people who, by being almost trapped in the same space, are trying to understand something very serious that happened to them. They try to interpret and understand the impact of a specific event on them. Consequently, they analyze their own coexistence, its characteristics and difficulties, the joy or the tyranny of its intimacy. In a perpetual cycle that also characterizes the structure of the artwork, the discussion of the protagonists and their self-referential analysis never ends. They destroy and replant the succulent Aeonium, in an endless process of endless confessional monologues. Each hero of the play addresses an interlocutor who never answers. There is a hint of dialogue, or at least a need for it. What could this never-ending verbalization of my characters towards someone else really mean? What exactly are these people saying? What exactly do we all say every day? And to whom? And above all, what is the outcome of this?