Elon and the Stars

Our landscapes of histories and the space above our heads

This text is part of ORTO, a publication by Roma Calling 2019/2020 Fellows in collaboration with Saul Marcadent, with contributions by Armando Bramanti, Dominique Laleg, Anaïs Wenger, Charlotte Matter, Pauline Julier, Real Madrid, Nastasia Meyrat, Urs August Steiner, Francesco Dendena, Kiri Santer, Johanna Bruckner, Romeo Dell’Era. ORTO is the result of a collaborative zeal between art and science and highlights the common desire to cross barriers and overcome distances, albeit symbolically. Conceived in singular circumstances—swift e-mail exchanges and long video calls—the book contains heterogeneous materials able to reproduce the fellows’ experience.

The contribution is part of a new research cycle by Pauline Julier, titled Là où commence le ciel which explores the space above our heads and its representations.

Maybe we are born into a landscape of history, as Donna Haraway writes. National history, the history of colonisation, the history of race, the history of subsoil and land use, the history of science and technology, the history of gender, of class, of stock farming, political and military history, the history of nature.

The complex landscape of history into which my generation was born in the early ‘80s had a hole in its sky. It was a gaping, growing hole in the fragile layer of protection above our heads offered by the ozone. We were told about the danger of the sun on our unprotected skin, and at the tender age of ten, I believed the blue of the sky would escape through this new hole and disappear into the universe. The threat was serious but it was possible to visualise this hole. “A hole is alright, we can fill it”.

The ecological situation in which we live today is of a very different order, an order so great that nothing can represent it. Neither a hole nor a patch.

Giovanni F. is one of the best acrobatic airplane pilots in Italy. He is the one driving the drone in my last video, shot on 27 February 2020 in the suburbs of Rome. After the last shot, Giovanni F. put away his equipment quickly because he was to inaugurate Genoa’s new airport, the following day. His plane was to carry the white smoke trail at the centre of the Italian flag, the same smoke trail he would release into the sky a few weeks later, to reassure the country.

But the inauguration of the airport never took place. Everything was suspended by the Covid-19 pandemic.

From then on, many people began to see the world from home. And seeing the world from your window, your balcony, your screen, means seeing the world differently all of a sudden. The focal length changes.

It is now the 24 April 2020, in the evening. From where I am, I see mainly the sky. We are suspended in time; our modes of attention to the visual and sound spectacle that surrounds us has intensified. And the sky is clearer than ever. Not the trace of an airplane. A few clouds. Many birds. And no certainty on the horizon, just a large pandemic void. Darkness falls slowly. There’s a wind. In the distance, I suddenly see a bright line appear. An immense dotted line, a string of perfectly aligned small bright lights. A nightclub laser? Not possible, they’re all closed. A sign? That’s nice. A message maybe? Yes, but from whom?

That suddenly reminds me of a story.

Once upon a time there were the Earthers.

One day, they suddenly captured light signals from afar. The signals seemed to recur according to a system, like the Morse code. For months, humans worked on deciphering it. In vain. Since they didn’t know how to answer, they had enormous letters dug in the Sahara desert. One hundred kilometer long letters so they could be seen from afar. Letters that light up at night. It took an enormous amount of work that lasted for years. Enormous excavators were brought in at great cost and also a large amount of electricity was needed for the strong lights. Almost all countries participated, because it was very expensive. Even from afar, the message of the humans can be read very clearly: “Sorry?” Some time later, they received a reply that said: “Don’t worry, it is not you we’re speaking to.»

Back to the line. One by one, I can count the dots of which it is composed. It takes me quite some time to realise that this colony of lights is one launching of satellites. I discover on the Internet that these 220 devices are on their way to their workstations at an altitude of 550 km. Before my eyes is the unfolding of the famous Starlink project aimed at offering broadband Internet connection all over the world. Faster than optical fibre, faster than lightning. Satellites in single file all over the sky, in low-Earth orbit. 12,000 devices for 2025, visible to the naked eye. Satellites that occupy our sky for more communications and prevent scientists from observing the stars.

This celestial line is the dream of Elon Musk, one of the largest fortunes in the world and founder of the space company Space X. While over half the humans are in lockdown, Elon, for his part, is launching rockets. These are not the first ones either. But it has taken us ten years to measure the extent of the damage of this celestial highway. Light pollution, accident hazard. Many scientists have expressed their outrage but in vain. The legislation is unclear. “It’s a bit like the Internet in the ‘90s, space is an area where everything remains to be done.”

This string of lights is therefore a message and, as opposed to the story of the Earthers, it is addressed directly to us. I can’t remember who it was used to say that a straight line is the ideal of Western modernity. A line wholly oriented towards its point of arrival. Frantz Fanon also spoke of the colonising straight line, the one that imposed its line on the African continent. Elon, for his part, is always one step ahead in the conquest. Tourism on the Moon and living on Mars. Elon’s target is infinity, that is the message.

The line disappears once it’s crossed the sky. As my mind wanders, I realise that my position—eyes raised to the sky—is the same as that of a seafarer seeking his shipping route on the star maps. We have been using the sky to guide our orientation for a very long time.

It seems that looking at the stars is looking at the past of the Universe. By the time the light of a star reaches us, it has already died out billions of light-years before. It is also the place of the future, say the astrologists. I think of my dead. The sky suddenly seems very crowded if each of us places all their lost ones in it. There must also be some forgotten gods and some ghosts up there. I wonder what leads us to seek figures in the stars and shapes in the clouds.

I decide to consult the Yi-Jing. We are living in troubled times. If we must turn to the sky and resort to decoding messages, then this Chinese Book of Changes, said to be the most ancient divination manual in the world, may offer some clues.

I ask: « will all end well ? Is everything going to be alright ?»

The throw indicates a 16 hexagram “Be enthusiastic”.

The image: Land below / Thunder above.

From the interpretation in the book, I gather that:

« Thunder comes resounding out of the earth:

The image of Enthusiasm.

Thus the ancient kings made music

In order to honor merit,

And offered it with splendor

To the Supreme Deity,

Inviting their ancestors to be present.»

Another version says: astonishment, thrill, impetus,

transmission of energy, bewilderment. But the Elements are in the right places

(the land below and the thunder above) and it is possible to motivate the troops.

The sky is black at the moment. A new bright line appears. Second launch. At the sight of this new straight line of satellite dots, I come back down to Earth and realise it is above all a question of territory. To whom does the sky belong? A line divies up a space. For years, this is how we have been sharing out land. Are these dots not the same ones we use to visualise borders on a map?

In her last book, Vinciane Despret explains with ornithologists that birds have a different way of living. They sing out their territory. “Far from turning it into private property owned by petty bourgeois seeking exclusivity, birds offer compositions that are both musical and geopolitical. Territories are ways of living together, while retaining the possibility of having a reserved space, safe from assault, in order to meet their reproduction needs.”

It is high time we drew inspiration from ways of living that are different from ours. We must multiply the worlds and the ways of living, as Eduardo Viveiro di Castro writes. In any case, open up our imagination.

Later that evening, I write a science fiction script.

All the world’s richest people have boarded Elon’s vessel that is on its way to Mars . The pilot is Tom Cruise. But on board, the atmosphere is tense. They cannot get away from the smell of our burning forests and cathedrals. Some of them are delirious; they think they hear the shouting young rebels who are jumping over the underground turnstiles because the tickets are too expensive. They even have hallucinations, around them, thousands of women rise from their seats giving the middle finger. Their vests are the same colour as those of the boat people on their rafts and the protesters blocking the roundabouts.

And suddenly, panic strikes.

There’s no more oxygen and not enough facemasks for everyone.

Outside, it’s dawn. The start of another day in lockdown. Birds are free and humans locked up. Someone sent me some photos of people in Rome erasing the stars of the flag of Europe from their car license plates and I don’t know what to do with them.

One month later, I receive a letter from Greece in response to my last video.

Kythnos, Greece, May 31, 2020

Dear Drone,

Your sound scares me. An insect-like siren more animal than technological, but then what stirs the air more than you. Even if your message is reassurance—and I’m not sure it is, even in Pauline’s film, which is the reason for my writing—the noise of your arrival, for this is how I gage your appearance, unnerves me, inevitably. I scan the sky for your technical body and, invariably finding it hovering over my own, I feel destabilized. I feel you watching me, and, not knowing whose control you serve, what arm of what state or body, I wonder who views me through you, and what of my information your vibrating body metabolizes, where this information is remanded, and so on.

Drone, though I dislike your sound, and your appearance, I realize now, addressing you, that your name I admire. Your long, single syllable that moves off my tongue and then lingers in the air there, like feedback: I like it. The resonating air, though, its empty skies, its breathing bodies, recording or recorded or remanded, remains a question. Within the thick garden walls of the Istituto Svizzero, protected from the city’s bodies and air, Drone, what did you see there? Outside the walls were:

Aires of pandemic and aires of violence and aires of protest, aires of jasmine and thyme and sage and petrol and teargas, and aires of Bergamot, the bitter orange that constellates the streets of an anarchist neighborhood where I claim an apartment. Aires in which the viral wanders quickly then languidly, catching some host body; and air in the throat that is stopped by a state and those it does not serve. “I can’t breathe” is how the body goes. “I can’t breathe” is the refrain of terror and violence and its last expression in language. AIRE that is an autoimmune regulator, a human gene expressed in the thymus.

Donna Haraway describes the immune system as a “biopolitical map of the chief systems of ‘difference’ in a postmodern world,” those differences being racism, sexism, colonialism, etc. She also talks about “odd boundary creatures,” which include cyborgs and women. I wonder about you, Drone, as a destabilizing boundary creature, although I apply it to you negatively: you who often serve those who enforce borders, exercise surveillance, impose boundaries between bodies viewed as people and bodies not. I’ll admit: I can’t stop thinking about bodies these days, my own and others. I can’t stop thinking about moving images and the language that fills them. In this I am not alone, I know. You’ll know, Drone, from watching us, that pandemic has filled our air for six months and now protest does. Bodies that were inside, for months, are now outside, for days and nights, filling streets and squares, opposing the state violence the state administers perfunctorily or perfectly.

On the island from which I now write you, the uncertain air is full of herbs, their oils unfurling like feedback in the lackluster heat. The air is unseasonably cool—winds from the north are cold and strong as they cross the Aegean—just as it was unseasonably warm last month, when a heatwave struck the city, and we lay stricken in our hot interiors in ecological collapse. The streets then were empty—one scenario of the apocalyptic—and the air was loud of birdsong, which was extra lucid in the absence of bodies and their machines.

Bodies and their machines: perhaps you see yourself in that sentence, Drone. Perhaps you just see me, a woman in running shoes on an empty beach in the Cycladic, closing her eyes on a pale sandbar under an empty sky. The airports are still closed, of course, or mostly, so the sky is absent our larger machines. Smaller ones, though, hover: the emergency helicopter, painted red as a mouth, that circled the village all morning, and last week, in Athens, the drone that crossed my neighborhood for an hour, then came close and trembled above my head as I read outside on the terrace.

Drone, I must admit: I flipped it off with my finger. In my native vernacular, I gave it the bird. I thought it was a police drone searching my neighborhood for bodies it deems criminal, that is, anarchists and migrants and refugees, but then my partner said he thought it belonged to our hippy neighbors, who we sometimes see on their terrace, doing yoga and sunbathing. Why would hippies in the year 2020 in a historical city in the Eastern Mediterranean own a drone? I asked him. He shrugged.

Haraway asks: “Can cyborgs, or binary oppositions, or technological vision hint at ways that the things many feminists have feared most can and must be refigured and put back to work for life and not death?”

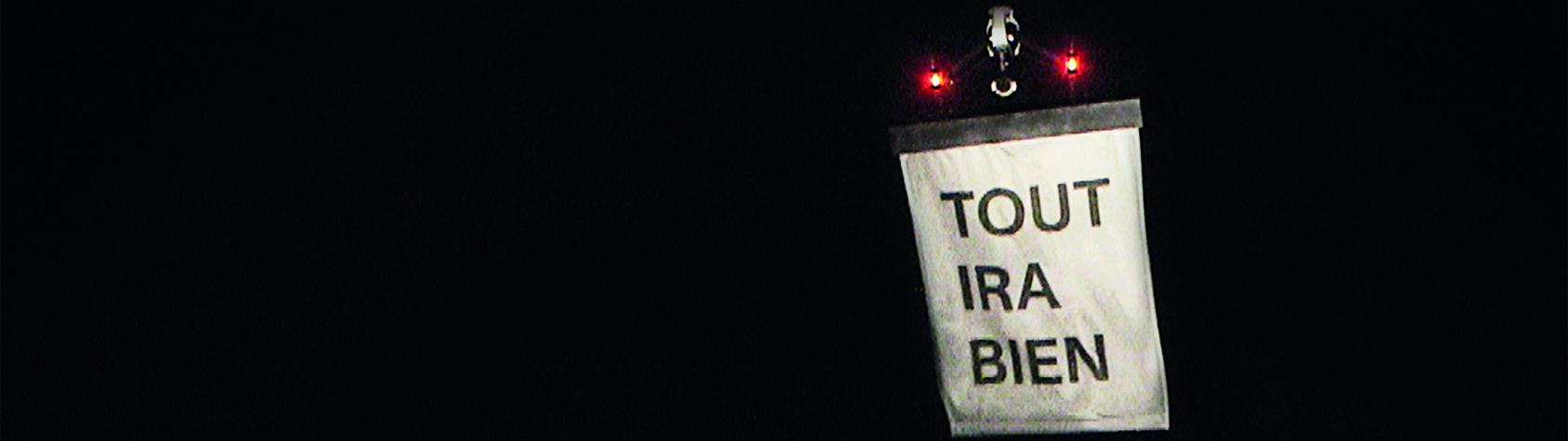

Drone, Drone, Drone: I give you language and you give me language. I take in air and you take to air. At least in Pauline’s video you do. Skittering across the screen, field of night—its blue-black sky and inky silhouettes of Roman pines—you come close to me. Your red eyes, camera-ready mouth. You drop your pale flag, surrender some language, a kind of physical comedy. TOUT IRA BIEN, your flag reads. You fly away to return, your buzzing, trembling body emerging from darkest trees: TOUT IRA BIEN. Again. Everything is going to be alright. A chorus of white flags, missives of reassurance, a hook of language—of support and faith—offered by the body of a machine I do not trust.

I begin to sing this hook, these words in translation, syncopated like a song issued from my birth city. In 2015, the Los Angeles rapper Kendrick Lamar released “Alright,” his track looped with that refrain of relief: “Everything is going to be alright.” This chorus was adopted by Black Lives Matter, whose movement offered it up into the air of the streets they filled and breathed: Everything is going to be alright [breath] Everything is going to be alright [breath] Everything is going to be alright [breath]. The line like a small machine: pumping the lungs, demanding breath for song and song for breath and breath for life and life for—

As I write you, Drone, the streets are again writ with bodies in resistance to racist state violence, to the state’s extraction of air from the black community. Drones hover above them. Moving images of moving bodies. TOUT IRA BIEN. Were you quoting them, Drone? Were you, Pauline? This letter is for Eric Garner and George Floyd, as much as for you.

On this late day of May in the year 2020 amid societal collapse, climate collapse, and global pandemic, drones are being used to kill locusts in Jaipur, to monitor anarchists in Exarcheia, to intimidate migrants in Evros, to clock protestors in Minneapolis, Atlanta, and Gaza, to militarize land borders, water borders, and suburban borders in the occupied territories and settler societies. Drones are being used by filmmakers to record images.

Drone, I am under your eyes, and yet today I watch you. I view you from my own small monitor, where, unsteady protagonist of Pauline’s film, you deliver a deft and absurdist message of—what—hope. A kind of Mercury or Hermes, depending on one’s location. That darkness doesn’t ground you—or that it does—well, this is my letter (of faith) in response.

Yours,

Quinn

Pauline Julier thanks Quinn Latimer a lot.