Ecologies of Feeling

Notes from IFFR 2019: a filmmaker reflects on a week’s worth of new films

Between late January and early February, Tijana Mamula went looking for inspiration at the “human emotions”-themed 48th International Rotterdam Film Festival. These are her notes on the movies she liked, in the order that she watched them. Contains spoilers.

At 10am on the first day, I ignore the dutiful voice telling me to watch something that won’t be released, and go see Vox Lux (Brady Corbet, 2018). The beginning is great. The nighttime shot of the terrorist walking, alone, on this empty, poorly lit suburban road. It’s so dead and depressing it almost justifies his actions. The shooting too, odd in its Bressonian, off-kilter acting, stiff and artificial, such a contrast to the drama. There’s something about this opening that takes the human emotion out of the high school shooting. Robotizes the responses. Empties that quintessential, overrepresented—or just mostly badly represented—twenty-first century media event of all its tragedy and pathos. And yet precisely by doing so puts all that back into it. Take, for example, Celeste’s convalescence: the synth sounds of her amateur keyboard moderating and modulating her singing, her guttural, “wordless” response to the trauma. A few scenes later, at the church memorial, their crutch-like artificiality carries over into her performance—the keyboard still there, still out of place—so that there’s always a shadow of something fake, something stilted, something neon hanging over the purported sincerity of her emotion, her negotiation of trauma through what amounts to expressive arts therapy. In the second part of the film, everything changes. For one, Natalie Portman reveals the true, untapped potential of her acting: it is capable of Cage-esque explosions. A fellow festival-goer said something like, “Just pure directionless pathos,” and that is exactly what it is. Portman cries and laughs and yells and rages and melts down, and it all seems random and de-motivated, but not in the sense of a plausible psycholability. It’s just pathos, moving from object to object as though of its own accord, detached from the person producing it. A feeling without a body. Affect, not personified so much robotized, bound to something standing in for a person. Rumor has it that the comedic effect of the film’s second chapter was coincidental, but I’m not so sure. Jude Law is also funny, truly funny, in a way that doesn’t seem unplanned. Most of all though, the humor strikes me as just another way of reaching the affect obliquely. More, that is, than of commenting on the origins and uses of disaffection.

Young Celeste (Raffey Cassidy) makes her first music video in Vox Lux (Brady Corbet, 2018).

Mens (Isabelle Prim, 2018). On the way back from a summer holiday, an adolescent boy sifts through a pile of documents relating to his great-grandfather’s murder. He is traveling home but also onward/back to Mens. In Mens, Jean embodies an adult detective and proceeds to investigate the unsolved crime. He is in period costume; most of the other cast members are not. There are horse-drawn carriages on the soundtrack; the police department’s transportation is contemporary. A key witness is diagnosed with hysteria; the psychiatrist illustrates what this means by scrolling through nineteenth-century photos on his smartphone. It’s an odd strategy: always disjunctive, and perhaps precisely because of that effective in its liminality. In other words, you’re never not aware that Jean isn’t really a detective, that it isn’t really 1895, etc. But by allowing the disbelief to sort of coexist with its ostensible suspension, the film actually creates a new past-present, reality-fiction dimension. In which the kid really is a detective, very competently going about his job in 1895. While watching, I didn’t like the cheap-looking camera work, DSLR-ish and overexposed, but in retrospect I wonder if it wasn’t intentional—a distancing device? Ultimately, the setting binds it all together. Young Maigret may not have been around at the turn of the nineteenth century, but the flora (or a lot of it) probably was.

A crime buried in history. Mens (Isabelle Prim, 2018).

In Program 3 of the Ammodo Tiger Short Competition, Paranon (Zeno van den Broek, 2018) captures my intellect. A black grid on a white background and an accompanying sound composition, both programmed to manipulate various parameters in canon structures (hence the portmanteau title). The complicated technology aside, it’s a lesson, and an effective one, in minimalist tension. A number of audience members felt (or claimed to feel) powerfully affected by it, assaulted even. I just thought it was interesting, for reasons that the director himself put forth best: “As soon as there’s two elements, you have tension and conflict, so something happens.” As soon as there’s difference, something happens. I want to write: as soon there’s two things with a difference between them, or, as soon as there’s two non-identical things… but that’s not it. The point is precisely the opposite. It’s the doubling, the two-ness, that creates the difference. The identity or non-identity of the elements is beside the point. Think of mirroring, paranoia, twins.

Parameter + canon = Paranon (Zeno van den Broek, 2018).

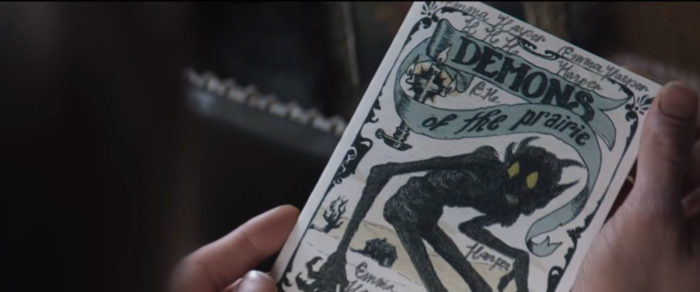

At 8pm that first day, I’m in the mood for a female-directed horror-Western. So I’m surprised when The Wind (Emma Tammi, 2018) turns out to be a productive and at least seemingly thought-through reflection on adaptation, or even, more broadly, on the relationship between image and word. At first it seems neither more nor less than what it says it is: a female (if not necessarily feminist) subversion of the genre, shifting the focus from the men who venture westward to the women who stay at home and wait. Soon though, unexpected sources start to emerge. The women read aloud from The Mysteries of Udolpho, from Frankenstein. They’re obsessed with some kind of demonology pamphlet. They keep diaries and personalize their Bibles. The references escalate into a full-blown conceit. Suddenly, there’s a trunk of books that travels like it’s got consciousness and agency. The diary dies in a fire then comes back as the wind. Doors slam shut like book covers. It doesn’t matter: words can just as soon break in through the window. It’s easy: the house is like a book and the book is indestructible. In the end though, it’s more than just a postmodern-ish commentary on Gothic fiction and women’s relationship to it. It’s more about bringing images to life. About the way books become hallucinations. “There’s nothing outside,” the characters take turns reiterating—suggesting, perhaps, that there’s nothing outside not of the mind, but of language. Nothing outside the word.

Words become things in The Wind (Emma Tammi, 2018).

Later that night, I’m still not tired of seeing violence. Out of Blue (Carol Morley, 2018) is possibly my favorite of the festival. A “nice poetic sort of literary detective film” was my first reaction, the only note I took before the movie got really good and I had to stop writing to just watch. Basically, Out of Blue, an adaptation of Martin Amis’s Night Train, starts out pretty flat and normal. Like a CSI episode without the psychedelic lighting. Or like any number of mainstream US police procedurals, only not as good. Restrained and English and kind of clunky. Almost theatrical. And then slowly, by tiny tiny increments, it starts to get weird. Not a flashy, surrealist, David Lynch weird, but a more subtle, insinuative, incremental kind of weird. Detective Hoolihan has an imaginary friend—maybe. She’s an alcoholic—yes, but not an unreliable narrator. The main suspect is the right suspect—it never is, so how weird is that? And the more you understand the story, the more you learn about what’s really going on, the more frightening it gets. A detective movie that actually scares, really scares, so that when you leave the theater you’re afraid to walk to your hotel room, swipe the card key and step into the dark—that’s the weirdest thing of all. Eventually, I realize this: that most mainstream, genre treatments of the detective/police procedural/crime story exist to cover over and devitalize, by sensationalizing it, the trauma of actual crime. I watch CSI not to be scared of (violent) death but precisely to not be scared of it. I like CSI because it turns trauma into spectacle, because it externalizes and spectacularizes the fear of trauma that otherwise just sits inside my body, quiet and voracious. In Out of Blue, Morley succeeds precisely in conveying the trauma as trauma. And she does that, I suppose, partly through a kind of self-reflexive strategy. The detective is “never affected,” we’re told, except for this one time. As a habitual attendee (viewer) of crime scene (investigations), she too experiences this particular event as an unexpected trauma. Turns out that’s because the trauma is her own: the violent death that marked her childhood and changed her life finally unravelled and resolved within the framework of this most recent crime. In other words, Hoolihan is to her career as we are to the genre: at long last witness to a crime that actually affects us because it tugs, more and more consciously, at the traces of our own dark histories—exhuming that which the genre (in many of its permutations, and most of its recent ones) exists to bury.

Detective Hoolihan (Patricia Clarkson) processes generic trauma in Out of Blue (Carol Morley, 2018).

Diamantino (Gabriel Abrantes and Daniel Schmidt, 2018): My notes: “so sexist + hipster heaven.” Well, perhaps not so sexist after all, or also not sexist, attempting as it does to gender-bend, and otherwise subvert, the romantic (comedy) genre. The zany story aside (a nationally shamed soccer superstar finds non-binary love as a result of being embroiled, courtesy of his evil twin sisters, in a plot to distract the masses from a right-wing political coup by cloning the athlete’s DNA into an army of goal-scoring heroes) I find myself inspired by the duo’s signature cinematography: grainy 16mm and 70s telephoto lens-work upended by corny postinternet VFX. And the odd disorienting, Laure Prouvost flash-cut. It’s poetic. Especially one moonlit hyper-romantic sailboat sequence, near the end of the film, that reminds me of the seduction scene in Barry Lyndon—only as earnest as Kubrick’s version was (purposefully) insincere.

The Beast in the Jungle (Clara van Gool, 2018). Another adaptation that I saw because it was an adaptation, this time of a Henry James novella. The director turns it into a dance film, extending the lengthy passage of time in James’s story, and the reflections on memory that accompany it, into literal time travel, the protagonists existing and reencountering each other across the entire twentieth century. The extraordinary thing here (and a lot of it isn’t) is the way the film, despite being largely wordless, is pregnant with words. Built around the exchange of gazes and the meeting of corporeal movements, it retains text through the very simple strategy of substituting spoken dialogue with dual internal monologue. By allowing speech to accompany the actors’ unspeaking faces, it invites us to imagine words being spoken even in the many moments when they are not, and so transforms the text of the literary source into the texture of the film. The strategy is not dissimilar to the sound-image disjunction of Marguerite Duras’s India series, only where Duras separates words from images in order to evoke other images, van Gool joins them to evoke other words. The novella, unread, untold, surfaces in our imagination. “The email draft and then the closeup—amazing!” And here too so many beautiful landscapes, shot (I think, and the director suggests) from the point of view of “the beast,” of death.

Death looks at the world. The Beast in the Jungle (Clara van Gool, 2018).

“Death everywhere—staring death right in the face. Also Maman, Maman, Maman” (Lucia Margarita Bauer, 2018)—where the director transitions from seemingly self-indulgent, irritatingly kooky home video footage of a dysfunctional family gathering into a homage to her recently deceased grandmother, so unrestrained in its confrontation with death that it’s almost pornographic. Repeated shots of the corpse, the family fussing over her outfit, her makeup, photo after photo (“she’s so beautiful”—and she really is), a lengthy, painfully detailed, ruefully funny recounting of the many mishaps, the absurd bureaucracy, that derailed the funeral preparations. I reflect that I may have actually never seen a film that is this much a death mask: unflinching, cathartic.

The filmmaker pictures her dead grandmother in Maman, Maman, Maman (Lucia Margarita Bauer, 2018).

But also birth. Embarrassingly, I cried through most of Els dies que viendran (Carlos Marqués-Marcet, 2018). Didn’t take a single note. I don’t have too much to say about it, except that it’s (to me) the most accurate-feeling depiction of what it feels like to be pregnant that I’ve ever seen on film. The cue, apparently, came from the actress (Maria Rodrìguez Soto), pregnant at the time, let go from her theater job as a result, and wanting to do something with it—not with the dismissal, but with the energy of the pregnancy. So she contacted Marqués-Marcet, an old friend, and they half scripted, half improvised the film over the course of sixteen months. The pregnancy is an accident. Vir jokes through the test, then cry-laughs at the result. At first they don’t want to keep it and then, in one amazing conversation—in bed, the night before the scheduled abortion—decide that what they do know is that they don’t not want it. Vir tells her mom, and they both cry-laugh through that too (“I’ve never heard her this happy,” or something to that effect). She runs errands, gains weight, loses or leaves her job—same difference. The couple grow closer, almost break up. Vir wants a natural birth, she’s adamant about it, the baby has to come out of her body like it’s supposed to. She gets a C-section. The film is interspersed with home video footage of her mom’s pregnancy with her, including the birth in all its painful, uncensored detail. Vir watches it and cries, in a take that, we’re told, lasted 57 minutes uncut. It’s a film within a film: a documentary within a fictional narrative, where neither one diminishes the reality of the other. Her baby is beautiful, Els dies que viendran is beautiful, the performance is unreal, perfect.

A pregnant Vir (Maria Rodrìguez Soto) attempts to enjoy oral sex in Els dies que viendran (Carlos Marqués-Marcet, 2018).

Genèse (Philippe Lesage, 2018). Another favorite. Lesage was already doing this in The Demons (2015), but here the film’s alignment with its adolescent protagonists is, also, perfect. A deeply personal story, he says in Q&A, about a pair of siblings navigating sexual awakening and social maturation—or social awakening and sexual maturation—over the course of a school year. It sounds a lot less interesting than it is. “Adults ludicrous,” I wrote: the drunk mom (passed out drunk), the touchy English teacher, the psycho History teacher (both embittered, both acting out like they’re the teenagers), the insensitive macho P.E. teacher. A coda of sorts—the unrelated story of a third kid’s summer camp romance—ends the film on a high note and redeems the world’s adult population through a single, guitar-playing, relationship advice-doling counsellor. Meanwhile, it’s the camera itself, and the film’s patient, chilled out narrative pacing, that gives the characters the space they need. It listens, like a good shrink. It waits for mistakes to be made; it’s still there in the aftermath, quiet and nonjudgmental. It sits and breathes, watches and empathizes. In moments, it’s almost embarrassed and in others (the most painful ones: the rape, the beating), it only wishes, maybe, that it could intervene.

A summer camp romance buds in Genèse (Philippe Lesage, 2018).

And then, Denis is Denis. High Life (2018) is full of unexpected conjunctions, non-sequiturs. I like how she only ever gives you 20-70% of the information you need to understand the story. Echoes of The Martian, except here the spaceship garden is restored to its rightful otherworldliness, its utopian impossibility. It’s so out of place there: the contrast is depressing. The spaceship is depressing, that life is depressing, because of this constant reminder of what should be there, what can’t be there, what may be (is) on the way to disappearance even where it does belong. Two scenes I loved: 1) the rape that, against all odds, doesn’t happen. Nice to see that dismal expectation being set up and then, for once, subverted. 2) After a couple of decades of awaiting new human contact, Pattinson steps onto a fellow spaceship only to find, in place of the warmth of recognition we so hope for, a horror show: dogs dead and dying, infected with god knows what, cannibalizing each other, in an infrared-lit, disease-ridden wreckage, like some far circle of intergalactic hell. The movie lives in these interstices between what we long for or expect—because the movie itself and the (cultural) histories it channels invite us to—and the exact opposite of it that we get. It’s a bleak picture, a nightmare ecology, the world reduced to one man, his daughter and their garden hurtling through nothingness on a piece of space debris. For a moment though, I find myself musing—happily, absurdly—that if there’s no animals on the spaceship, they must at least be vegan.

Tcherny (André Benjamin) tends to the prison-spaceship garden in High Life (Claire Denis, 2018).

A different sort of enclosure appears in Life After Love (Zachary Epcar, 2018). I picked this out of the entire video library right after watching Denis’s film, probably—or in retrospect, definitely—because I needed to be told that there is life after. It’s just shots of cars and people sitting inside cars, parked or stuck in traffic or whatever, but it’s great. It’s supposed to be a reflection on the way cars serve as meditative spaces after break-ups: “sanctuaries for emotional renewal.” It felt like, I wrote in my notes, “actually kind of a new way of looking at things,” and like any new way of doing anything, it’s kind of hard to describe. A lot of it is sunny, the kind of too bright, disco-ball sunny you only get inside and around cars. Reflective surfaces everywhere, windows, mirrors, everything transparent and closed off at the same time, overcrowded and isolated. As I remember it: telephoto lens, mostly closeups, very linear pans and tilts, 16mm. The editing is rhythmic but syncopated (“great edits too, real visual poetry”). It’s relaxing in a free jazz sort of way, where you have to let go and accept that you don’t know where it’s going. The whole thing does feel meditative (it feels like hours of sitting inside cars, aware of your surroundings but focused on something else, waiting for something to happen, for your mind to shift gears), but also musical—not so dissimilar, I guess, to a lot of Altman’s The Long Goodbye. Which is maybe why, despite having no idea where the film was shot, I felt sure it was Los Angeles. It’s good like a certain kind of really good poem: one that isolates a specific, mundane feeling and describes it more precisely than anyone’s ever bothered to, so that it’s both really obvious and completely new.

“Around us are Austins and Rovers afar / Above us the intimate roof of the car…” Life After Love (Zachary Epcar, 2018) reminds me of John Betjeman.

All These Creatures (Charles Williams, 2013). I thought it was a documentary at first, then an experimental essay film, then a narrative one. Also new, in a way. In voiceover, a young man, maybe even adolescent or just recently come of age, tells the story of his father’s psychic unravelling. It’s impressionistic, meandering, obsessive, returning in loops to the sights and sounds of an insect infestation (“all these creatures”), their effects as horrifying, their nature as inscrutable as the inside of his father’s mind. Accompanied by the narrator, we circle around the psychosis. It’s likened to a host of natural phenomena. It doesn’t do anything quite so circumscribed or describable as ebbing and flowing – instead, it storms up like the night sky and burns out like a field of locusts. It has twilights and dawns. It lives through seasons. The film is as grainy and dusky as the memory of what happened, punctuated by resurfacings of crystal-clear events. One sunny day his father picks him up from school, lucid and levelheaded, perfectly cognizant of what’s happened to him and the effects it’s had. He starts talking, explaining, apologizing, justifying, railing against the phonies of the world (he doesn’t say that but he might as well have), the kid gets distracted, the film with him, and they hit a dog. Like most film festivals, IFFR 2019 has a lot of dead dogs. At this point, I get distracted, incapable as I am of processing violence against animals at anything near the speed required to keep up with the average film narrative. But I think: at least this actually happened; he didn’t kill the dog to make the movie work. Did he?

The protagonist’s father battles his inner demons. All These Creatures (Charles Williams, 2018).

I sneak out of the final day short film marathon to go watch Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old (2018). I’ve been told not to miss it and wouldn’t have anyway, since it promises to fulfill my deep-seated drive to experience the feeling of war—as much a terror of actual conflict as a compulsive consumption of its fictional renderings. And for a second, it almost does. Jackson’s postproduction extravaganza starts out like a well made but unremarkable WWI documentary: voiceover interviews with soldiers, archive footage and photographs (in black and white), the odd non-photographic document, like a newspaper clipping or illustration. The narration is chronological, moving through the declaration of war, the recruitment of volunteers (all too often underage), the weeks of training for the uninitiated, deployment to the front. There are a lot of facts—recounted with an unexpected dose of rather British humor—and very little pathos. And just as you start to wonder whether you’ve misunderstood, and look around for the fourth time to check that everyone else is also wearing their 3D glasses, the camera steps inside the trenches. Very effectively, Jackson doesn’t use a cut to transition here but does so within a single shot. The black and white saturates into color, two dimensions morph into three, the sound blows up, literally, the flatness of individual human voices and the distance of recollection giving way to the relentless noise of close-up war. And for a moment or two, it kind of seems like you’re there. I’m not so sure it recreates the feeling so much as makes it fathomable, or not entirely beyond the reach of imagination. The lack of pathos, so matter-of-fact and dismissible in the first third of the film—just another dry documentary, you think, makes sense—becomes here maybe the core of its power. Jackson doesn’t tug at your guts or pound on your brain, doesn’t try to literally traumatize you into an emotive response to the state of war. Rather, he presents facts, as vividly and accurately as he possibly can: by restoring the film stock and infusing it with the color it might have had if only the technology had been a little more advanced; by orchestrating an array of voices into an enormous amount of physical, material detail; by recreating the sounds of those specific weapons in that specific environment; and so on. You “feel” like you’re there for the minute or so that it takes your brain to adjust to the shock of multichromatic three-dimensionality. After a while though, you start to imagine the outline of what ten million dead soldiers might have looked like, the echo of as many dying horses. This audiovisual experience, this seeing and hearing what is there and also more than what is there, delivers not the trauma of a personal tragedy but the consciousness of a collective one.

To the trenches. They Shall Not Grow Old (Peter Jackson, 2018).

I end the day with the Tiger Award winner, Present. Perfect. (Zhu Shengze, 2018). No wounded canines or war horses here, but there is a visit to a pig farm that almost made me walk out fifteen minutes into the film. Six or seven years ago this would have been exactly my sort of thing: a plotless found-footage narrative woven together from hundreds of hours of mainland Chinese live-streams. The director visible only in the edit and the monochrome presentation. The lead anchors are a motley crew: a burn victim, a disabled sidewalk artist, a factory worker affected by hypogonadism, a street dancer—able-bodied, just really bad—and a beautiful, 23-year-old single mom, also employed in a factory. It’s hard to say whether their lives are actually uneventful, or whether the events have been strategically excised. The result, in any case, is discomfitingly private. I’m fidgety at first, then increasingly reluctant to leave my seat. It’s not the obvious merits: the clever commentary on an uber-contemporary cultural phenomenon, the glimpse into an online China that most of us Westerners would otherwise probably never see. It’s something else. Sympathy? They’re all likeable—no wonder, that’s probably why Zhu chose them. Empathy? My one note, a line from the single mom talking about her four-year-old daughter: “She was good today. She put on her pants by herself. She brushed her teeth by herself. Then she gave me a massage.” That made me cry. But it’s not that. It’s more like a slow erosion of prejudice, of hierarchy. A displacement of sympathy and empathy that carries away with it that complacent sense of my own superiority—the fearful, arrogant assumption that that could ever have been me.

A live-streaming anchor observes his changing surroundings in Present. Perfect. (Zhu Shengze, 2018).

The housing block holograms around in End of Season (Elmar Imanov, 2018).

Sunday. End of festival. End of Season (Elmar Imanov, 2018). This strange, slow movie grows on me. It’s late summer in Baku, Azerbaijan. A dysfunctional family of three—once young parents, now estranged; post-adolescent son incongruously giddy—sit around with electric fans on, possibly wanting to talk and definitely not succeeding. The buildings are new and tall and all the same. By day we see the jungle of structures, by night the windows: a sea of impenetrable lights (lives). It’s a story of human relationships, still languishing, as far as I can tell, under the weight of capitalism. It’s Antonioni today and not in Europe, but I don’t see that until halfway through the (inexplicably hypnotic, like every Antonioni) film, when the family goes to the beach and the woman disappears. I start to watch it as a remake and suddenly it’s amazing. Like that moment in Pickpocket when you realize it’s actually Crime and Punishment and at all once the novelty of this particular configuration of lights and settings, bodies and camera angles, becomes imbued with the different pleasure of recognition. It’s like seeing about a dozen films at once: the End of Season on the screen, and inside it, like a hologram, glimmers of L’avventura (the sea), L’eclisse (the fans), La notte (the endless, pointless conversations)—those strike me as the most obvious references. I think the film knows it, because in one dreamy, transitional sequence the night view of the housing block really does start hologramming around: the buildings floating closer together and farther away, superimposed, each one the same and not the same as the one behind/beside/in front of it. It’s a good movie. It drifts, first, but then it throws down an anchor and just lies there, patient and weightless. So maybe it’s not a movie about relationships, or (post-)capitalism, or immigration, or not only. Maybe it’s also a movie about movies: about the lightness of the medium and the weight of its history.