Eccentric Talents

On “Prizing Eccentric Talents ΙΙΙ” at P.E.T. Projects, Athens

Escalating the few steps down P.E.T. Projects artist-run space information flows. Artist and founder of the space Angelo Plessas and curator George Bekirakis have mounted an exuberant show which given the small size of the site might at first seem over the top. I need to hold on to something. I find it in Athanasios Argianas’ delicate sculptures Consonants as Noise (Oyster, 7m Aegean), (Oyster, 4 m Argosaronic) (2015). Reminiscent of handrails, these brass formations bear traces of the artist’s swimming and diving routine around Attica when he returned to Athens from London to be near his ailing father. Oyster shells and rock scallops, marked by depth and location in the work titles, are attached on the structures like they cement themselves to rocks. Both solid and fragile, unclassified, they evoke memories and scratch the subconscious. Having experienced loss recently, they speak to me about grief, aging and healing, evoking loose connotations of handles helping the ill or disabled and at the same time of our somatic relation to the sea, its creatures and its promise of freedom and wellness.

Juxtaposing Argianas’ works with one of Lucas Samaras’ iconic fabric collages, Composition 105 (1979), the curators bring to light two different stories of reconciliation with loss. Samaras, the Greek-born American pioneer artist, bought his first sewing machine in the late 70s, living in the US and started working in fabric as an homage to his mother who had died two years ago in Greece without him being present. When first showing the works in his solo exhibition at Pace Gallery Samaras said that these were the sheets to wrap his mother in. “They have value. They’re not beautiful, but it’s the best I could do for her.” This curatorial gesture of affect opens new ways to relate to a historic work even for those who are already familiar with it. Not everybody is. Plessas and Bekirakis insist on the need to present Greek historic artists, including those of the diaspora, to a younger audience and their idiosyncratic way of doing this has its value, in the much-debated terrain of (un)learning the local art history.

As the ambiguous title “Prizing Eccentric Talents ΙΙΙ” suggests, with this ongoing series of exhibitions the curators raise the question of what could a prize be nowadays, researching its ritualistic and value-creating aspects, but also using the concept of prize as a prompt to think spontaneously, a kind of “algorithmic curating.” Merging their personal and impulsive selection of works with researching the important private local art collections and bibliography as well as Plessas’ interest in AI and commitment to creating networks between different communities and generations, Plessas and Bekirakis propose a sui generis take on an “algorithmic” exhibition trying to resist any kind of curatorial homogenization. Their prize does not come with a fee and they are clear about it, nevertheless, they try to create alternative networks testing the possibilities of the art economy and the formation of cultural capital, in what might be seen as their own input in the urgent debate on the sustainability of artists and artist-run spaces in Athens today.

Back in the 70s Michalis Katzourakis used to order his sculptural “ensembles” by phone giving simple instructions such as “divide a cube of X dimensions into six,” and his colorful polyester and aluminum geometrical pieces in the exhibition (Groups 66.B, 2012 and Group A.1, 1970) seem to suggest a search for genealogy for an artist such as Plessas having a year long experimentation in machines, digital production and AI as well as fascination with geometrical symbols. Seen along with Gabriella Simossi’s white resin sculptures (La Visiteuse, 1986, Les Ailes, 1983) evoking ancient Greek sculpture but in a weird way, the alienated, fragmentary, even ready–made nature of the later is highlighted in a way that becomes current and makes you want to learn more about this mis-represented historic woman artist who once send a photo of one of her sculptures instead of her portrait for a book indexing artists of the time.

Interesting links and paths to think on can come out from bringing together, in such an informal though visually condensed concept, works by Greek avant garde artists like the ones named above and contemporary sculptors of different generations. Dora Economou’s oversized flip flop made of craft paper, although more informative and less uncategorized than other bodies of her work, exposes its fragileness and desire to grow in dimensions. These works were made as a result of Economou’s journey from Japan to Brazil, which the artist named “Sayonara”, a Japanese farewell, akin to the English “Farewell”, but which in Greek strangely means flip-flops. According to Google, when flip-flops arrived in the 50s, the movie Sayonara with Marlon Brando was popular. The poster showed the Japanese lead actress wearing traditional thong sandals, leading to the name migration for the greek flip-flops. Economou likes to tell stories working with what she calls “elephant” materials, that is, heavy but soft, having a difficulty to support their own weight. Most of them are surface materials, they don’t hide the processes that happen on them. The current discourse on the memory of the material, the gender, geographical and social context present in sculptural decision making, tells a lot about the art of a whole generation of artists working with sculpture in Greece, among which Economou holds a special position.

Newcomer artist Niki Analyti’s works have a more subtle presence, exhibited near the electric power supply of the space: a glitched artificial brain, replica of a computer motherboard, also known as the machine’s brain made of pins (Ι will never tell chatgpt about us, 2024), and an electric panel framing printed electrical circuit boards portraying Hydra, a mythical creature that, if decapitated, spawns two heads (Hydra Settlement, 2024). These soft-technology replicas of hard machinery that could have gone unnoticed, bear poetic, human layers on technological materials.

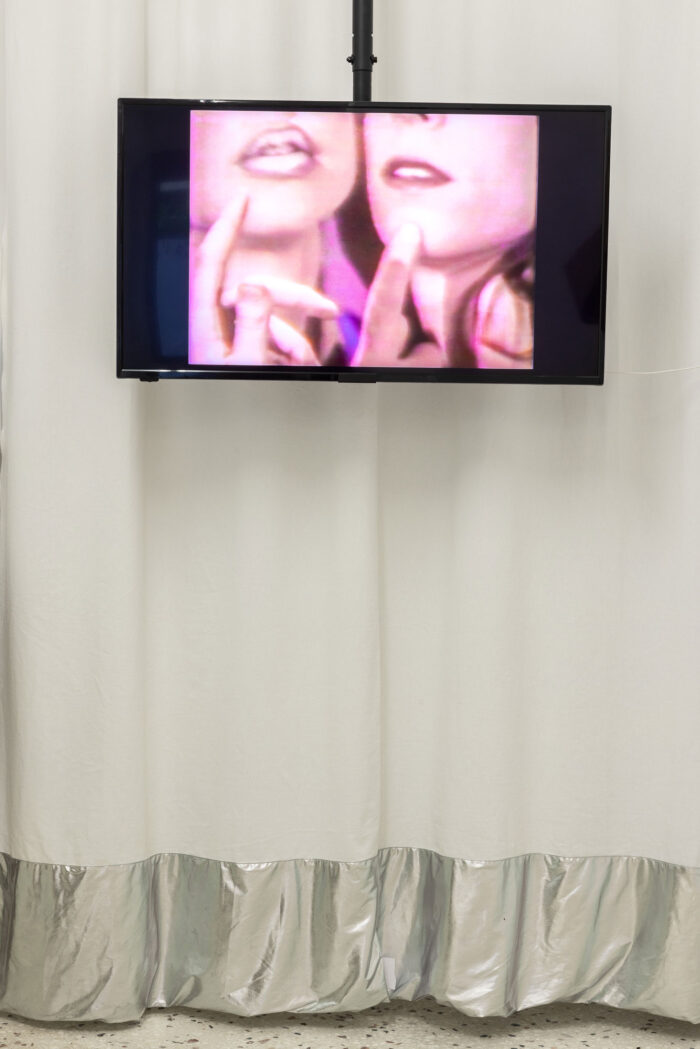

Next to the entrance, in Lynda Benglis’ seminal video “Female Sensibility” (1973) two women are kissing, unobstructed by the noisy soundtrack of men preaching and yapping on different occasions. Their unidentified indifference poses complex questions on self-representation and commodification. Flowing through space, though not imposing its presence, Marina Xenofontos’ “Solar Sail” (2022) seems like a connecting link between different works of the exhibition. Originally conceived as an open-air installation in the island of Anafi, this set of plexiglass tubings captures and reflects sunlight beaming down on its spine of spinning mirrors and refracts it through the water encased in it creating subtle waves of rainbows on its surface and the surrounding land. Here, it manifests the power of (industrial) material to hold images and memories.

This play between the remoteness and intimacy of the technological and the manufactured, making space for affect, poetry and occasionally humor, gives us a lens through which the most interesting dynamics of the show appear. Less powerful is the cohabitation of more obvious visual connotations, namely among Ariana Papademetropoulos’ symbolic painting Atmospheric River (2024), depicting a classical interior disrupted by a vibrant wave bursting through its pedimented door, flooding into the exhibition space to meet Jannis Rafailidou’s video explosion of dead birds illegally hunted, which fall back from the sky (A sign of prosperity to the dreamer, 2014) and Simosi’s feathered body “neoclassical” sculpture. Or Rafailidou’ s Lick me (2024) sculpture, where the tongue-like rubber flooring that comes from horse stables along with the neon sign reading the work’s title, extorts us to approach it in a more descriptive way than more complex works of her ongoing study addressing humans’ relationship with animals.

In another gesture of looking back to his roots, Plessas likes to include an older work which had been influential for him when he first saw it. This time it is Maria Papadimitriou’s billboard poster Martin Martin (1993), depicting the melancholic face of the artist asking Martin why ever did he take her May away. Originally made for the fifth Biennial of New Art in Poland, it is said that the artist put it up all around Athens on the occasion of Martin Kippenberger’s show in Eleni Koroneou’s gallery expressing her complaint that her own show was postponed because of his. This was the beginning of a long-year friendship and collaboration between the two artists that did not know each other before. Looking at Maria’s face I think of many things. I think of the power dynamics between what twenty years ago we called periphery and center and now address as localities and alternative geographies. I think of gender and de-colonizing. I think of the artist’s image, the artist as image, cultural capital, networking, precarity and sustainability. In the late ‘90s, Papadimitriou and her generation of artists and curators were among the first to think on the cultural producer as a subject in a media-centric world and the emerging dynamics of the institutions and politics of contemporary art. Their story, among other stories, has not been yet written and the lack of references for younger artists has left its marks on the art produced in Greece still.

Maria’s billboard is presented in the backyard of P.E.T. Projects, along with Olga Migliaressi-Phoca’s Led Lightbox reading “APPLAUSE” (2020), like the ones found in recording studios instructing viewers when to clap, and Byron Kalomamas plastic and metal palm trees (The fantasmatic cylinders, 2016), part of a larger project representing the artist’s perception of specific time cycles through variation in the tree’s diameter. These works, unlike Papadimitriou’s one, do not really add much to the exhibition’s narrative, besides creating an open space to hangout and reflect on what you have seen. A typical Athenian backyard facing the back balconies of the nearby blocks of flats. P.E.T. like to ask the neighborhood what kind of art they like to see and they keep asking for neon light works once they have first seen one. Fair enough.

Afterall, “Prizing Eccentric Talents ΙΙΙ”, like P.E.T. Projects itself does not pretend to be more than it is. An extension of Angelo Plessas’ practice, bringing people (and machines) together and testing alternative forms of knowledge production and emancipation. A safe space of experimentation and sharing, of building long-lasting relations and methodologies rooted in the local conditions of working and making art, different from the dominant geographies—and that’s not a small thing.