Due Pitture Seleniche

When outdoor painting was forbidden

Ruth is a collector of writings, a site dedicated to grey literature, unpublished and experimental texts, conceived by Manuela Pacella, born from the pleasure of writing and reading. We are very glad to host a text each month, selected from one of the sections of the four-headed Ruth: Yellow Dog, Hungry Ghosts, Free Spirits, Brain New.

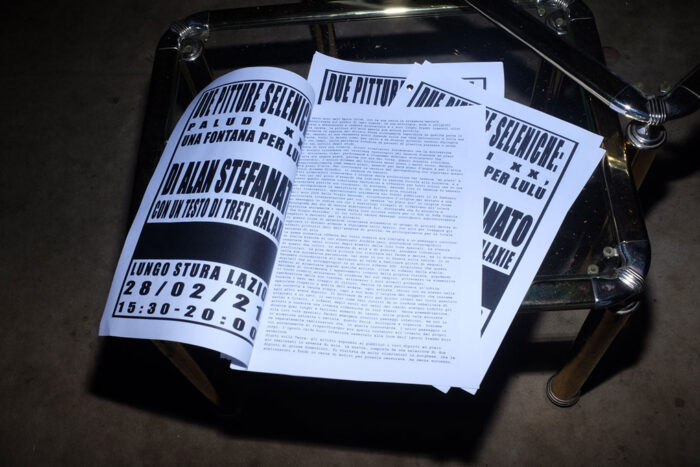

This month we chose from Yellow Dog Due Pitture Seleniche, a text commissioned to Treti Galaxie by mrzb for the one evening presentation of two new paintings by Alan Stefanato, happened the 28th of February 2021 at Lungo Stura Lazio in Turin, mrzb headquarter.

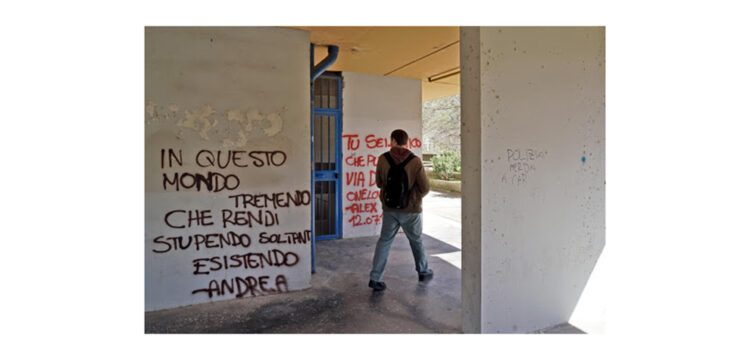

In the third year of the Age of Chloé, with its mind-streaming series customized on each user’s profile, its mythologies, fashions and religions imposed and abandoned on a daily basis and its long, cold, ash-colored sunsets, outdoor painting was still forbidden.

Although the reason for the prohibition was certainly available somewhere on the net, no one had really queried its true motivations and its origin, everyone thought of it as a given fact and for several solstices no one had been painting in the open fields, in the suburbs punctuated by pressed-plastic buildings or even in the courtyards of the studios.

Instead of researching, some researchers argued that the motivation for the ban laid in the tautological character of the French phrase en plein air. Through videos, performances and modular holograms, they declared that the air was always full, as it was never empty. This concept solved, ruining it, the ancient dilemma of the half full or half empty glass giving it unequivocally as always full, being it half full of water and half full of air. In order to keep selling merchandise with this ancient philosophical dilemma, the term had been banned.

Other researchers researched the origin of the prohibition in the term en plein, used in gambling to indicate the roulette jackpot, and considered annoying and offensive by all those who in a given game didn’t win. Virtually, according to them the term had been banned to protect the sensibility of those who lost at roulette.

Other researchers, specialized only in the records published on February 23rd, in 2000 by Virgin Records, traced the origin of the ban to a particular interpretation according to which the phrase en plein air was originally a coded message with which illegal musicologists referred to the entire discography of the electronic music duo Air, a discography that was banned and destroyed solely because of their soundtrack for Sofia Coppola’s film The Virgin Suicides, whose title contained messages considered subliminally negative and deviant to youth.

In this time of magnificent academic uncertainty, a group of artists decided to circumvent the ban going out in space to paint, not just to examine the pictorial effects caused by the absence of gravity, but mainly because of the complete lack of air.

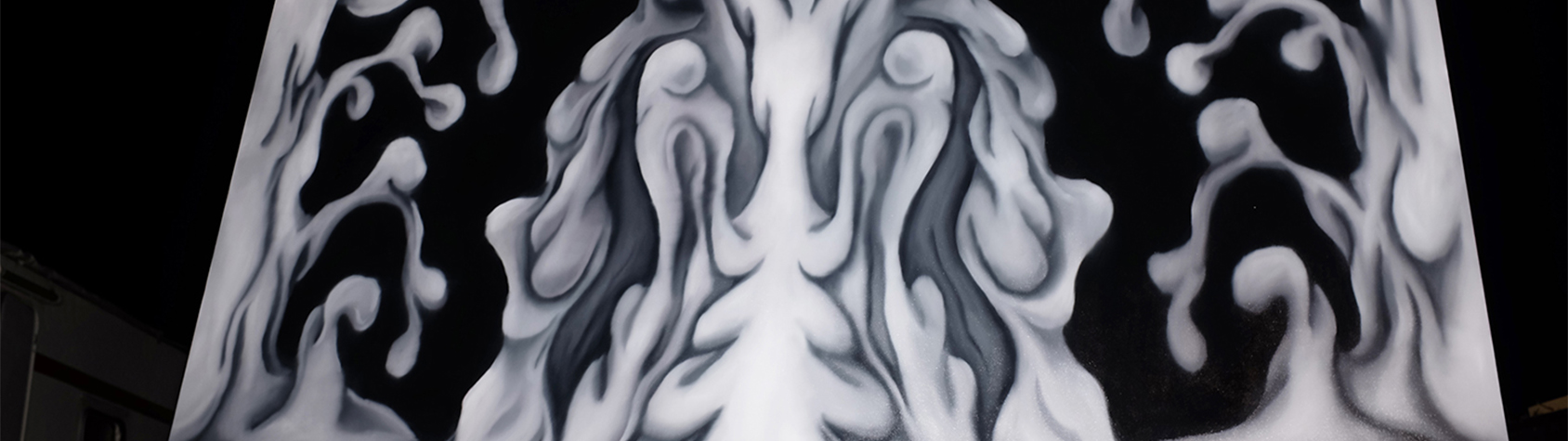

The chromatic spectrum offered by the cosmic void was limited to a continuous landscape of white stars on an immense black backdrop, inconceivable depths observed through the curved glass of the helmets of their spacesuits. The layering of these two colors, in the absence of air and gravity, assumed particular vibrations. The laying of the paint was never firm and sharp, but became so in its subsequent perception, in the way it fixed on the retina, a phenomenon referable to the getting used to the warm and familiar glitch of digital signals that overlap on an ancient LCD screen. They discovered that this effect intensified when some artist, in addition to the reflections of the stars, decided to consider the inner misting of her visor, looking at the cosmic void through the condensation of her breath, through the symmetrical ramification of her trachea, through her pulmonary alveoli.

On the way back, while the ship was in the outward journey’s specular orbit, each artist, closed with herself in her hermetic bunk, understood in her own way the origin of the subjects she had painted together with the others. Floating alone for days in absolute emptiness attached to a cable, feeling like fetuses fed by an umbilical cord of kevlar and titanium, the reflections of the stars on the glass of the helmets had induced the artists to conduct an intense reflection on themselves. Without premeditation, during those long and tiring moments of work, on the great canvases anchored to their spacesuits they brought out involute inner landscapes, not from an abstract or mental point of view, but from a physical, biological and organic one. Together but separately they realized that, under those circumstances, the only landscape in which they felt sincerely reflected was inside their bodies. The unknown warm inner darkness observed in the light of the unknown cold outer darkness.

Once on Earth, the artists exhibited to the public their paintings en plein air made in the absence of air. The exhibition, consisting of a selection of two large paintings, was visited by many undercover researchers, who analyzed it in depth looking for reasons to censor it, without any success.

The organizers, while self-reviewing the pictures of the project on the site of one of the main art magazines, because of a mistake in the insertion of some keywords, found by chance the documentation of Alan Stefanato’s solo show Due Pitture Seleniche: Paludi XX, Una Fontana per Lulu, curated by mrzb and set up on the northern banks of the Stura river on the outskirts of Turin. To their utter dismay, the works made by the artists in outer space were absolutely identical to those painted by Stefanato in that distant February 2021.

Moreover, the text that accompanied that old exhibition told about their recent experience in the void, and was identical in every word to that written by them, which, moreover, ended this way.

Translated by Giulia Lenti.