Dream House

Agata Ingarden at Piktogram, Warsaw

Agata Ingarden works with multiple media and her sculptural practice expands to combining installation, video, performance, sound, writing and collaboration. Her practice is driven by material research as well as investigations in post-humanities, sociology, science fiction and mythical narratives.

“(…) sometimes if I touch my hand

maybe it’s not mine but someone else’s

and it seems like there is no difference.

You fuse and detach and it’s painful.”—Agata

In her famous retelling of the Daphne and Apollo myth, Meret Oppenheim depicts an alternative finale of the story, rather than solely focusing on the metamorphosis of the female protagonist. In her rendition of the tale, both god and nymph are changed. The right-hand side of the oil painting shows Daphne, in her mid-transformation: her bright pink torso morphs into a laurel bark, hair becomes a bushy tree crown spreading against a turquoise sky, her feet—now roots—merge with lush grass. To the left stands Apollo, undergoing an evolution of his own, his body turning into a hearty, bulbous plant. Circling the patron of the Sun and arts are insects—possibly butterflies—their pale, semi-transparent wings fluttering around the changeling. The figures in the painting lean towards one another, as if trying to establish contact: Apollo reaches out to Daphne with his awkward sprout-like limbs; she bends towards her partner as if to comfort him. The scene depicted by Oppenheim appears peaceful, sentimental even, and still, one starts to wonder what thoughts race through the human-plant minds of the characters. Even though they don’t seem to resist their metamorphoses, do they strive for connection to ease the pain and angst that accompany them in their last moments in an anthropomorphic form? Discarding one’s previous life—willingly or not—is never an easy process after all.

Even though mythology is never referenced directly, in her compact yet precise show at Piktogram, Agata Ingarden manages to tap into and actualize equally grand themes of longing, struggle, search for kinship, and growth. In Warsaw, the artist presents artifacts—sculptures, moving images, sounds—referencing “The Dream House”, a fictional “simulation-like parallel reality”. First manifested in 2021 during the Future Generation Art Prize exhibition in Pinchuk ArtCentre, in Kyiv, and since then reemerging throughout Ingarden’s career, “The Dream House” does not easily bend to definitions. It’s hard to pinpoint its exact status: occasionally its descriptions suggest a place, while other times: a moment. Ingarden refers to “The Dream House” as her long-term research project and indeed, her approach might resemble a scientific methodology: the artist carefully designed the conditions of the experiment and in her subsequent exhibitions reports on its developments, disclosing more details about the enigmatic dimension.

The conceptual contours—and the core mechanics of “The Dream House”—have been based on interviews with the artist’s friends, precursors of the “Butterfly People”, inhabitants of this mysterious realm. When viewing the show, we learn that the place they occupy allows for fluidity between subject and object: the “Butterfly People” exist in a symbiotic relationship with “The Dream House”, acting as both influencers and the influenced, hosted and hosts.

Even though “The Dream House” is a place of constant metamorphosis, its descriptions suggest a safe and welcoming territory. At Piktogram, we witness an attempt to get closer to the core of this strange world. The viewer entering the gallery is greeted by human voices, fragments of the aforementioned conversations with the “Butterfly People”—emitted by Mushroom Brain (2022), placed further inside the gallery space,—and Dream House Program (2021), a video installation, hung to the left of the entrance. The screen split in four shows CCTV footage of a curious gathering. Four groups of people in a corridor of an unassuming office building, move—dance, crawl, sway—to four distinct soundtracks, composed by Wladimir Schall, each melody drawing from a different music genre to influence and direct the behavior of the performers. The piece itself works as an autonomous commentary on the authority of a seemingly neutral, standardized architectural style of office spaces serving as a background for the performance, , although its goal in the exhibition context is to provide the viewers with information on the mechanics behind “The Dream House”. Through the description of the work, we learn that the whole system is powered by the emotional and physical energy of its inhabitants: “their feelings, emotional states and sweat becomes the fuel, the energy that keeps the program working.” [1]

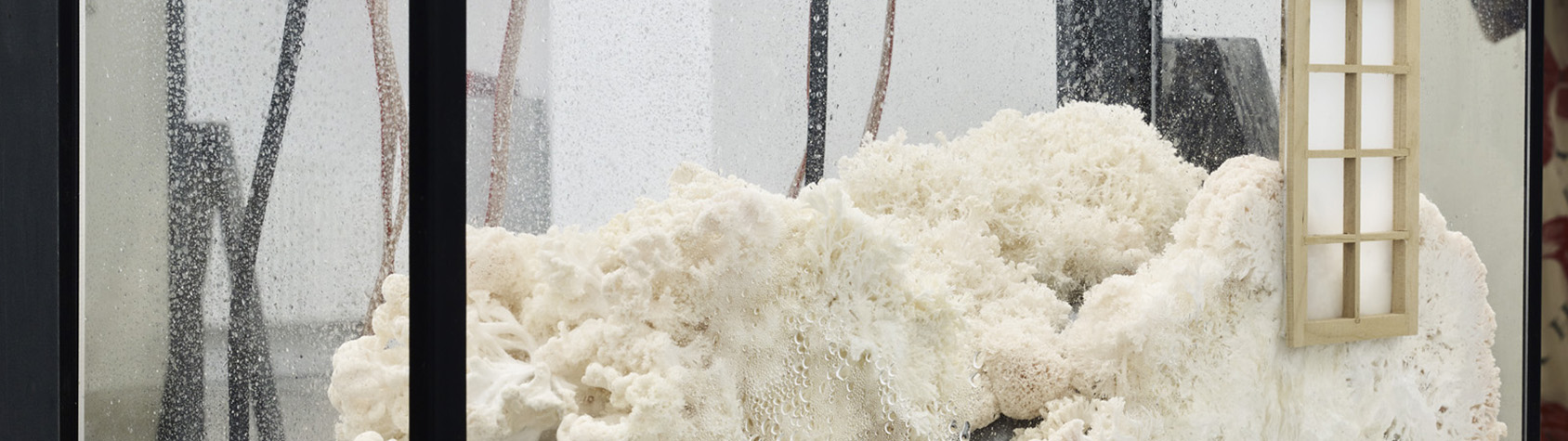

In the center of the gallery sits the source of the sounds echoing through the space and the system’s nucleus. The Mushroom Brain (2022) a towering structure of heavy steel frames, cables and electronics, serves as a dwelling of a Lion’s Mane mycelium, sprawling inside a plastic cubicle. The mushroom is linked to the speakers via cables monitoring its electromagnetic activity. Based on the readings, an algorithm selects fragments of the conversations Ingarden held with her friends. Each corresponding with a different interviewee, the five compact speakers alternate in diffusing disembodied voices describing individual visions of what “The Dream House” may or seem to be. What’s important in the case of Ingarden, dreams and desire are not vehicles for escapism, they rather work as a source of guidance and courage to forge relationships.

The characters detail their individual experiences of inhabiting the fictional world, their testimonies echoing science fiction and cyberpunk classics. At the same time, the recounts are laced with a need to belong: finding a place of one’s own, a connection, a home.

Highlighting the dynamics between a group and individual and arguing for a fluid delineation between “me” and “we: The Mushroom Brain connects to the most elaborate and spectacular piece on view: Inside the Dream House (2022-23), an installation consisting of five large sculptures (Dreamer 1-5), each representing a “Dream House” dweller. The core structure of the sculptures is identical: the portraits of the “Butterfly People” are constructed from dim solar control glass, supported by massive black frames, identical to the ones used in the architecture of the “Mushroom Brain”. Each supports an office suit, repurposed and customized by the artist into a bizarre costume, and an assemblage of copper wire and tree branches. Dreamer 1 is a case in point: the jacket has been printed in silk screen patterns, adding patches of bright color to its somber grey material. The back of the suit signals a transformation in progress: it has been ripped open, revealing butterfly wings dyed in pale blue. The figure gently leans toward the glass, as if to admire its reflection or in an attempt to break free. The remaining specimens carry an equal amount of tension: one stretches its wooden hand beyond the surface of the glass (Dreamer 5), the other (Dreamer 3), its human characteristics almost entirely absent, spawns a bouquet of delicate insect wings, emerging in place of the torso.

Similarly to Oppenheim’s Daphne and Apollo, Ingarden shows the “Butterfly People” in the climax of their metamorphoses. Empty shells outgrown by their owners are discarded and replaced by new, airy vessels. Inside the Dream House shows the human, machine, fauna, and flora merging into one. Despite this, the transformation is not an effortless process: the twisted figures, in poses reminiscent of marble baroque masterpieces, evoke a sense of discomfort and stress accompanying them in transiting into the new and unknown. Interestingly, the “Butterfly People” hybrids resemble their real-life insect counterparts in one other aspect: the butterflies’ nervous systems do not have the same pain receptors as the ones found in humans. They cannot feel pain as we, mammals, know it. And yet, they flinch when touched, cower in face of a threat and wWhile visiting the exhibition at Piktogram I caught myself wondering about the response in a butterfly body produced during a transformation of a caterpillar into an adult specimen.

Free from simplistic idealizations, Ingarden’s show managed to generate a sense of empathy towards the unimaginable and unexplained. Although a large part of the intentions of its citizens and the logic behind the mechanics of “The Dream House” remain an enigma, the project successfully incorporates the toil behind the process of self-empowerment and developing self-awareness, and because of this one finds its protagonists surprisingly relatable. Hopefully, in Ingarden’s future work, the nature of “The Dream House” will be understood fully: only then, its accommodating character can be duplicated and the community it allows thrive, expanded.

[1] Agata Ingarden, “THE DREAM HOUSE WORLD 2021-2023”, a PDF sent to the author by the artist.