The Synthetic Sacred

River Claure, “Ekeko,” from Warawar Wawa (Son of the Stars) series, 2022, photograph

In 2020 we crossed a vital tipping point: For the first time the weight of human-made mass surpassed that of all global living biomass.

The emerging synthetic ecologies are expanding and threatening holocene life, while disproving the western idea of our bodies as somehow being discrete. The reckoning begins internally with the microbes and minerals that make up the human body and accelerates as the advances of science and technology transform and complicate life. New hybrid bodies and landscapes are in the making; within them the man-made and naturally occurring merge and reconfigure.

Microplastic particles are being found in the placentas of unborn babies, the shifting layers of earth’s strata include machinery, and chemical waste is re-coding genetic structures. Meanwhile, for better and worse, the latest advances of science and technology are pushing hybridity to extremes by reengineering life. Examples of hybridity include: 3D bioprinting, soft robotics, neural interface technologies, synthetic biology, and artificial intelligence. The porosity of the material borders between the synthetic and organic are thin and they are getting thinner. These developments raise questions about what constitutes life, consciousness, and intelligence as well as what futures are being ushered in.

The experience of thinness within today’s synthetic ecologies provides a new meeting point between post-industrial hybridity and pre-industrial indigenous cosmologies. In doing so, thinness creates an opening for a redemptive relationship with hybrid ecologies guided by a sacred appreciation of an all-encompassing natural intelligence. As the representation of the Tiwanakan deity, “Ekeko,” in artist River Claure’s photograph expresses, hybridity can be transformed from something entrapping and toxic into something joyful and liberating. Whether it’s placing plastic flowers on a shrine at the corner of the street, decorating a tree or dressing up as Ekeko, the act of creating a sacred assemblage–including those combining plastics and toxic substances–points to the possibility of reclaiming an alternative, sacred, future for synthetic ecologies, and with it the potential for “detoxification.”

THIN PLACES IN ART

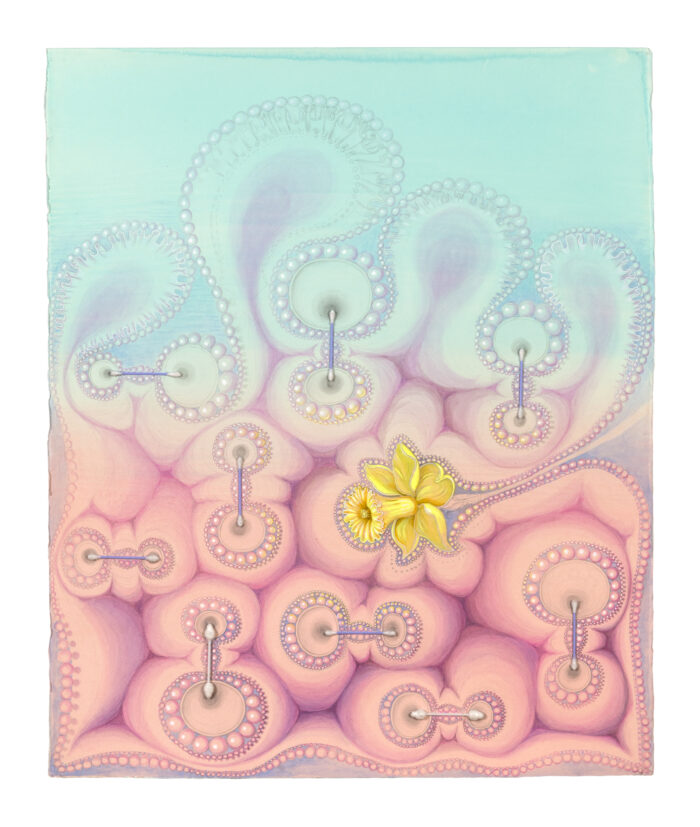

Kinke Kooi, “Visit (3),” 2019, 80,5 x 66,5 cm acrylic, (color) pencil, gouache on paper

It’s easy to be lulled in by the synthetic

pastel aesthetic of Kinke Kooi’s intricate drawings

but this belies the power contained in the

uncomfortable intimacy of Kooi’s liminal bodies.

As a form of felt and embodied knowledge art is well placed to operate in thin spaces and interrogate their transformative potential. Art can work with what is not fully rationalized or understood, and has long been entwined with spiritual practices. It can enable us to integrate, on a deep level, what it is to live within the hybridity (and destruction), and ask questions about the kind of world/s we want to live in.

In recent years, two fields of art practice have been growing in parallel: one that explores technological change and shares interests with New Materialism and Post Humanism; the other comes from the lens of indigenous cosmologies and decolonialism. In the examination of our relation to nature within the context of climate change, these two fields are beginning to converge. In doing so, they intersect with eco-feminist, feminist, and queer perspectives which operate in similarly liminal and oppressed ontologies. This convergence is yet to be fully theorized and brought to popular consciousness but offers a new point of thinness within the art world. If combined these fields of artistic and theoretical research could offer radical insights into how we move forward.

SACRED ONTOLOGIES AMID HYBRIDITY

The Lustymore Man (left) and the Dreenan Figure (right),

are Janus-like figures signifying a portal between

the past and present. Evidence is inconclusive but

the sculptures are widely thought to have Celtic origins.

The idea of thin borders has a long history and existence within spirituality and metaphysics. In the Celtic tradition, for example, “thin places” are liminal sites in the landscape or moments where it is possible to walk in the physical and the spiritual world simultaneously. Often resonant and uncanny, thin places are thick with energy and offer an encounter with the sacred or divine. “Thinness” hints at hidden depths to reality, the possibility of a greater meaning or intelligence that does not only belong to the human mind.

This meeting point between the realms, bodily states, or eras is visible in many ancient belief systems–from the rock paintings found in caves such as Lascaux or the bird-headed dance of the shaman specific to many cultures such as the Yanomami in the Amonzonian basin. Looking at today’s material hybridity, the features that apply to prehumanist[1] nature-godded ontologies can also be applied to scientific and technological developments. The “strange” ontologies that characterize posthuman hybridity have more in common with prehumanist cosmologies than the scientific revolution they emerged from.

WHY WE NEED THE SACRED NOW

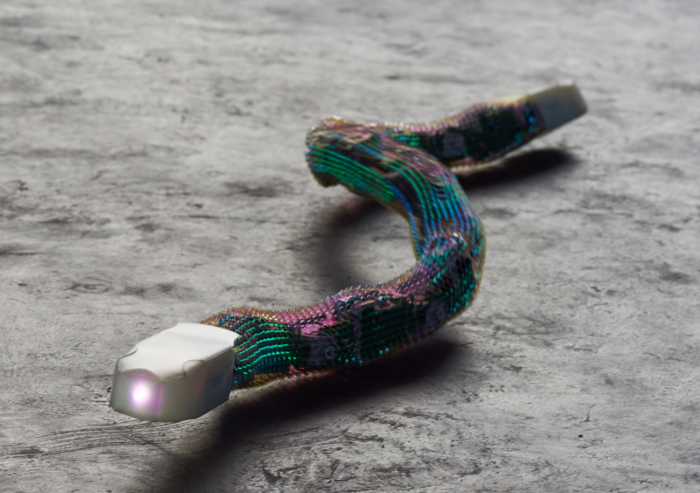

Pamela Rosenkranz, “Healer (Waters),” 2019. Installation view of If the Snake, Okayama Art Summit curated by Pierre Huyghe, Okayama, 2019

Pamela Rosenkranz’s “snakebot” moves and responds

to electromagnetic rays and visitor’s devices.

Uncannily alive with sensors, algorithms and

broken meanings (in particular, the ancient Greek association

of the snake with healing), Rosenkranz’s snakebot gestures

toward the future present of hybrid ontologies.

Through the new hybrid landscapes, materials, and creations the uncanniness and mystery of life is being reasserted even amidst the destruction and disorientation. Thinness exists within the unsettling strangeness of hybrid assemblages and with it, is the opportunity to reconnect with the sacred.

Just when holocene life is threatened, the sacred offers a methodology, a way to reorientate and transform our relationship with hybrid ecologies. It does this by reconnecting us to the all-encompassing mystery of life, and nature, in deep and embodied ways. As a dynamic unfolding of being-in-this-world, the sacred encounter implies values of co-existence, kinship, and respect. The sacred can provide a framework for how to let nature guide the development of hybrid ecologies–even the most highly synthetic. Appreciating nature’s sacred mystery and intelligence can inspire us to develop and craft our innovations in ways that are generative, as opposed to careless and extractive.

PART 1: Re-imagining fractured relations

The role of artists is to take us to thin places. To shine light on contemporary experience and explore the meaning and implications of the past and futures enfolded within it. If done with purpose (not just performatively), art can be a site of sacred encounters that are grounded in the mystery, uncertainty of the synthetic present. These encounters can enable us to feel fear in a safe way and hopefully reconfigure the fear into a new understanding, bringing clarity, catharsis, and hope.

In the contexts where there has been a separation between humans, nature and the sacred, art can help reorientate and connect. When art operates as a space of open experimentation, research, and exploration it can cross fertilize ideas and belief systems.

FRACTURED RELATIONS

1

2

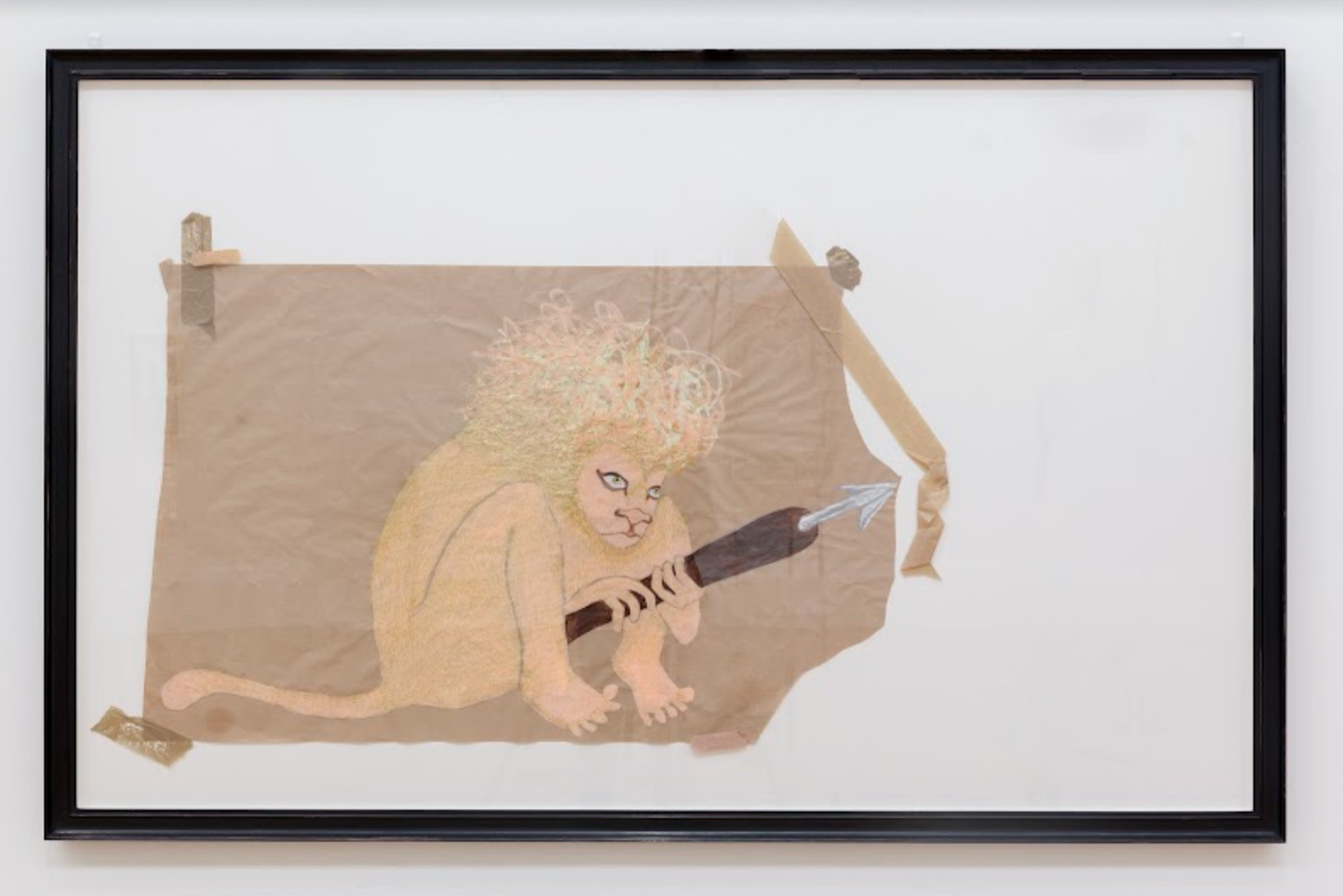

1 Jesse Darling, Relics of the Lion Wound, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa, London. Photography: Tim Bowditch

2 Jesse Darling, Brazen Serpent 2, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa, London. Photography: Tim Bowditch

3 Jesse Darling, Lion in wait for Saint Jerome and his medical kit, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Arcadia Missa, London. Photography: Tim Bowditch

The Ballad of Saint Jerome,

an exhibition by Jesse Darling,

addresses the religious, political, and

cultural myths and ideologies internalized

in western modernity with its white

male gaze. In particular, how

modernity’s brokenness is

“a kind of death cult” that wounds

and entraps bodies –human/animal–

but also how it is brokenness,

its “abscess” or hollowness,

can be a source of renewal.

Ancient cultures across the world tended to share a common sense of themselves as intrinsically part of nature while also revering its power and mystery–this has often been expressed through nature-godded cosmologies. The break with a sacred relationship to nature has been gradual and occurred at different points in history, differently within different cultures.

In the west, a heady mix of enlightenment ideals of humanism, reason, and progress, combined with industrialization and capitalism sought to release humans from the wildness of nature. These forces broke the connection and turned the cut already made by Christianity into a material rupture. But, the break was never complete; contemporaneous critique, esoteric practices, and other forms of expression continued at the margins. The baroque, for example, ran alongside the enlightenment, expressing “irrationality” through dynamism, mystery, and the untamable power of nature.

Colonialist expansion and extraction, enforced the break elsewhere, violently erasing and covertly co-opting prehumanist knowledge and practices, a process that continues today. Yet, where indigenous cultures remain strong prehumanist practices continue, even in postindustrial landscapes in which the relationship with nature is fractured. Here, in the UK, a younger generation of artists are understanding the destruction of Druidic culture by the Romans through the lens of colonization, while a resurgence of gothic aesthetics connects to the baroque.

Of course, many prehumanist cultures had their own tyrannies too–such as oppressive and violent social hierarchies. It would be a mistake to romanticize a pristine state of nature (or society) as an opposite of the advances of science and technology; the two need to be combined, with compassion and in the messiness of the present, for a more hopeful development to occur.

ENTRAPMENT IN HYBRID ECOLOGIES

Video Agnieszka Kurant, Animal Internet, 2018. Animatronic mechanisms, custom programming, artificial fur, plants, rocks, sand, webcam lifestream; presented as a video loop. Commissioned by MIT CAST. Scientific and technological collaboration: Adam Haar Horowitz, Owen Trueblood, Ishaan Grover, Agnes Cameron, and Gary Zhexi Zhang

The continual colonization and extraction

of nature entails the creation of ever more

elaborate forms of engineered nature,

with Animal Internet, Agnieszka Kurant

imagines the end result: “the entertainment industry

crosses over into the production of ecotourism

at scale; where simulated natural environments

are accessible only online and operated by

offshore workers.” Animal Internet is made up of

found footage of surveilled animals and artificial

animals whose movements are authored by

behavioral and sentiment data gathered from

Amazon Mechanical Turk workers and various

protest movements. “Nature becomes a construction,

a platform, and a source of profit like any other.”

Despite being undermined (both theoretically and practically, by the products of its own making), the false binaries and mantra of positivist progress cemented in the enlightenment persists today. These empty narratives provide a convenient rationale with which to justify and continue capitalist and colonialist exploitation. In this context, emergent ecologies entrap, extract from and replace life, both synthetic and organic, while the destruction of holocene life continues unchecked. Thinness points to the sacred, but its potential remains unrealized.

While the reengineering of life is driven by these axioms the future looks dystopian. What becomes of nature, for example, when microdrones take over for extinct local pollinators or self-learning robots patrol the reefs of the Pacific, injecting invasive starfish species with lethal toxins? And who or what controls life, natural and synthetic, when nature is increasingly bionic? This question becomes more pressing in the context of digital capitalism; as artist Agnieszka Kurant, points out, “digital biospheres” can be easily quantified, manipulated, extracted from, and even hedged against.

Unsurprisingly, for many, the future present of science and technological innovation feels threatening and induces a mix of anxiety, grief, and rage. This may be felt even more acutely by those in colonized cultures where once again their lives are being threatened by behaviors not of their making. Artists are responding to this backdrop in a variety of ways. For example, some explore the hybridity, highlighting its meaning and impact on life, and tell new (and often catastrophic) stories about posthuman ecologies. While others foreground and reclaim prehumanist knowledge and technologies to heal and remediate. Thinness offers an opening to move beyond dystopian scenarios and both sets of practices are well placed to explore it.

SACRED GUIDES WITH WHICH TO REDEEM NATURE’S POWER

When reimagining nature deities for her new

AI simulated artwork Seven Acts of Nature’s

Devastating Dance, Kinnari Saraiya wanted

to think about how nature–as a creative and

destructive force–responds on being pushed to

her limit: “Placing the Mother of Nature Worlds

upon a golden throne of turmeric sands, studded

with precious gems of rain drops, she dances on

the heights of Kailasa. All the gods gather round

her as the world trembles at the sounds of

her ghungroo bells.”

The metamorphosis and indeterminacy emerging in synthetic ecologies, is a reminder of prehumanist ontologies in which a sacred relationship with nature existed. Focusing attention on the uncanniest (thinnest) manifestations of posthuman ontologies conjures back up the bigger natural power and mystery that contains them. Unchecked extraction and growth may destroy holocene life, but nature continues. As many indigenous cultures know well–humans must respect and be guided by the power and intelligence of nature, rather than view themselves as separate or superior to it. Appreciating this may not always be comfortable, afterall, nature is something we, as a species, have variously sought shelter from, tried to tame and appease. Nature is unstable and entangled, as dark as it is light and as destructive as it is creative–but this is where power, beauty, and hope reside.

A broad set of stories, objects, figures, and critters reaching across time embody the sacred and can be reimagined as symbolic guides with which to mend fractured relations with nature. These guides express thinness in their very being and in doing so have the power to bring together posthuman and prehumanist ontologies.

Atoms in quantum states and other queer phenomena[2] such as, lightning, pfiesteria and stingrays, combine with tentacular critters[3], like spiders and jellyfish. Spirit enthused rocks and earth, nature deities, the objects and rituals of nature-godded cosmologies dance with mythical deities, monstrous demons and creatures. Each guide has their own specificities, all speak of an ontological complexity that is vibrant, sensitive and with the power to reorient how we design our synthetic creations in accordance with nature. Paying heed to their complexity can teach us to transform toxicity and entrapment into a flourishing polyphony of intelligences and agencies, both synthetic and organic.

RE-IMAGINING THE PAST TO BIRTH A NEW FUTURE PRESENT

Excerpt from video by Morehshin Allahyari, She Who Sees the Unknown: Huma. Courtesy of the artist, 2016

Quantum-like time plays a vital role in the act of reimagining symbolic guides; the past, present, and future are materially enfolded in any one moment and this opens up the possibility for redeeming fractured relations and reclaiming oppressed knowledge. Artist Morehshin Allahyari’s concept of “re-figuring” explored in her long-term project She Who Sees The Unknown ( 2016–ongoing) is instructive here. In this artwork, Allahyari re-imagines the Jinn, Iranian mythical female shapeshifters. By embracing the “monstrosity” (thinness) of this powerful, yet misrepresented and repressed group of figures Allahyari aims to reimagine another kind of present and future. “I hope” writes Allahyari, “to give birth to new beings and becomings that are able to challenge and change the power structures.”[1]

In the process of redesigning the future present, decolonized quantum temporalities are required, rather than linear progress. Just as the Ekeko representation in River Claure’s photograph suggests: the point is to embrace the potentiality of non/existence contained within the place of thinness, for this asks us to reflect: what do we want to take forward and what do we want to leave behind?

PART 2: Art that gestures toward redemptive relationship with hybrid ecologies

The question of what to carry forward from the past or present and what to let go of is key to redeeming dystopian hybrid scenarios. As more artists explore the thinness of hybrid ontologies in the context of environmental destruction, they open up portals to a powerful natural intelligence that stretches across time. It is this intelligence, and its decolonialization, which is the guide to answering the question of what to keep and let go of. It tells us that hybrid ecologies that pollute and entrap must be reconfigured. There is great value to pursuing technological and scientific advances but these must be directed by natural intelligence in all of its complexity–its materials, ecologies, and indeterminacy.

Artworks by Oslo-based artist Ane Graff and Mumbai-based artist Sahej Rahal both gesture to the problematics of hybrid ontologies and pathways, intended or otherwise, to their redemption. Graf’s work can broadly be seen as situated in the exploration of hybridity while Rahal’s invokes prehumanist cosmologies within a high tech present.

Graff’s work explores how the biology of bodies are being remade by products of science and technology which are ingested and mutate within us both inadvertently and by design. It also connects to wider questions concerning synthetic biology and how we collaborate with microscopic life. Rahal’s work explores life in the machine and freedom from entrapment. In doing so, Rahal is part of a wider trend of artists probing the life-like qualities (motion, intelligence, intentionality, sensing…) that arise out of developments in technologies such as machine intelligence and robotics.

BODIES REASSEMBLING: INFLAMMATION AND HEALING IN THE WORK OF ANE GRAFF

In the work of Ane Graff, the body becomes our thin guide. For Graff, the body is inextricably permeable and interwoven with “external” environments (landscapes, products, social relations) and “internal” (microbiome) both inherited and contemporary. This challenges the notion of ourselves as discrete entities. In her sculptures, such as Patches of Standing Water (2021), for example, the body is released from its skin, recomposed into brittle assemblages where there is no divide between the human and nonhuman.

4

5

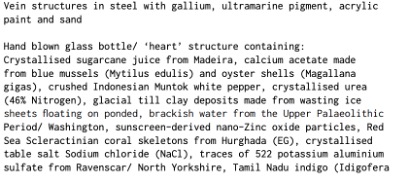

4-5 Ingredients list for Patches of Standing Water, 2021

The ingredients list and footnotes that accompany Graf’s sculptures are essential elements of the work and reflect the toxicity and complexity of today’s material entanglements. Encounters between microbiology, chemicals, minerals, metals across eras and geographies crystallize and inflame the physiology of the body. As more and more human-made materials pollute the environment they mutate and remake bodies, the resulting inflammation is correlated with an increase in chronic disease.

In Graff’s work, the lack of distinct boundaries, make the body a site of inflammation but also open up future/pasts of healing. Understanding the body as existing within and made up of ecologies is essential to both states. This is most apparent in a series of works created by Graf in collaboration with Tal Danino. In his work as a biomedical engineer Danino researches how bacteria can be manipulated to perform new functions, in particular to sense and treat pathogens in the body. The sculptures created by Graff and Danino point to a growing field of futuristic synthetic biology but in doing so inadvertently pose questions about what to carry forward from the past and present and what to leave behind in this brave new world.

Ane Graff and Tal Danino, "The Goblets (P. Mirabilis)," 2020

Ane Graff and Tal Danino, "P. Mirabilis," 2020

In these works, the geometric beauty of formations made by the bacteria and its shapeshifting ontologies serve as a reminder of nature’s intelligence even amidst the most high-tech creations. In P. Mirabilis (2020) a work by Graf created with Danino hand blown glass goblets stand in for the body and contain the aptly named Proteus Mirabilis, a bacteria commonly found in the human gut. The rapid swarming behavior of P. Mirabilis expresses the beauty and indeterminacy of nature’s intelligence. On the one hand, the rapid swarming behavior results in a natural geometric order that lights up the brain’s interoceptive neurons with pleasure. On the other hand, the same swarming behavior enables this bacteria to take advantage of a weakened immune system–it shifts from being beneficial to pathogenic. Intelligence manifests within thickly entwined and dynamic ecologies.

Seeing the body as inextricably part of these ecologies offers a pathway back to the sacred and possibility for redeeming high tech futures. If practiced in estrangement from a holistic understanding nature, the results of attempts to manipulate and control life could be devastating. Past/presents of medicine and environmental stewardship practiced by indigenous shaman–early microbiologists–can be a guide in ensuring that medicine is developed with respect for external and internal ecologies. Through careful plantsmanship the Amerindians, for example, managed to eradicate most infectious diseases without upsetting the natural balance. This stands in stark contrast to both the sheer quantity of diseases brought with the arrival of Columbus to the Americas, and to the “war on germs” approach that has dominated western medicine with disastrous consequences.

It is, as biologist and social anthropologist, César E. Giraldo Herrera, points out, the colonialist practices of translation and “purification,” that led to the distortion, decontextualization, and repurposing of indigenous medicine, and helped fuel the wider estrangement from nature. Decolonizing biology is essential, at the very least, so as not to repeat the same mistakes (like the war on germs) in our increasingly biotech future.

STATES OF ANIMATION: POSTHUMAN MACHINES AND EMBODIMENT IN THE WORK OF SAHEJ RAHAL

Video by Sahej Rahal, Mythmachine (excerpt from simulation), BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead curated by Kinnari Saraiya and Niomi Fairweather, AI program voiced by Niyati Upadhya. Photo: Rob Harris © 2022 BALTIC

Tentacular guides animate and occupy thin spaces between the physical and simulated worlds created by Sahej Rahal. These quasi sentient guides move, splutter, spew and shed their oily skin across ambiguous pathways which at once suggest a post-human future and possibilities for redeeming a primordial state of polyphony and coexistence. Witness to today’s mass extinction event and the kinds of politics that enable it, these guides invite us to reimagine the conflicted myths shaping the future present.

Inspired by fossilized and encrusted remains of relics, resembling clay and oil, manifested by loosely coded neural networks and animated through sound made in the gallery space; like all thin guides, the beings Rahal creates in his work reach materially across space and time and speak of phenomena that are at once recognizable and unfamiliar. In the case of Mythmachine (2022), recently on show at the BALTIC, the tentacles gently occupy physical space too, searching out detritus (leftover materials from previous exhibitions) and reconfiguring it to create sculptural companions to the virtual creatures. These guides are of the earth but posthuman, post-waste, post-extinction.

Video by Sahej Rahal, Mythmachine (performance by Payal Ramchandani), BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead curated by Kinnari Saraiya and Niomi Fairweather, AI program voiced by Niyati Upadhya. Photo: Rob Harris © 2022 BALTIC

The viscerality of sound is used as a way to reflect on and move beyond exclusionary politics and philosophies that deem certain forms of intelligence or life as superior to others. In the case of India, this is the ethnopolitics of Modi’s government which reinforce the hierarchies of the caste system, in the west it is the prioritization of the human over nature and mind over body. The virtual creatures move, light-up and spew according to the sounds made in the gallery space, for example by the bells on the Kuchipudi dancer’s feet (the lowest form of caste are said to come from Brahma’s feet), but, as Rahal likes to speculate, could just as easily be the rhythms of nature beyond humans or when humans are long extinct.

By centering primordial ontologies of sound and an uncanny aesthetics of decay, impurity and uncertainty, Rahal’s guides move us beyond the limits of language to embodied experience. In doing so they offer opportunities to imagine other ways of being and a state of nature that includes all forms of intelligence and animation. While also being witness to the destructive implications of the politics and behaviors which could ultimately be part of our own extinction.

PART 3: Synthetic sacred

What might technological and scientific advancements look like if guided by nature’s intelligence? Taken a step further, the developments explored in art like that of Graff and Rahal could point toward a future present of biologically cultivated machines, medicine and materials that are less toxic and polluting. Developments such as growing computer chips from fungi and computers powered by algae are already well underway. The question is whether this is done in ways that are truly sympoietic and generative (perhaps even healing), for the ecologies they exist within or whether they essentially continue an extractive and exploitative relationship with nature.

Moving beyond a destructive relationship with hybrid ecologies and toward a redemptive one, means operating “responsably” within the complexity of the shifting ontologies–the thinness (and thickness)–they express. It’s not easy; the synthetic sacred is messy, conflicted, and unstable. This is a kind of futurism that is not “clean” or slick, it demands an even more sophisticated version of “high tech” which does not only look forward. Instead, the notion of the synthetic sacred carefully recombines the past and present, it asks what knowledge, practices, and behaviors to take forward and what to leave behind in order for holocene life to be part of nature’s ongoingness.

A set of symbolic guides–stories, objects, figures, and critters–offer pathways to redemption within each hybrid encounter. As posthuman and prehumanist ontologies begin to converge, more artists are discovering these thin guides and have the potential to use them to examine and navigate hybrid ecologies. By holding space for the sacred power these guides embody, reconfiguring them in order to “birth new beings and becomings.” The resulting art can hold a critical mirror up to dystopian aspects of the present and experiment with as yet unimagined alternatives. Overlook the transformative power of this practice at our peril, for it is this that needs to be harnessed now, more than ever, if synthetic ecologies are to be part of a diverse–sacred–flourishing of life.

[1] The use of the terms “prehumanist” and “prehumanism” link to Sylvia Wynter’s critique of how, in the context of colonialism and modernity, European man positioned himself as the epitome of humanity and superior to nature. Prehumanism could be lossely understood referring to nature-godded cosmologies (often referred to, in a western lens, as animist) that existed before and/or outside of the Abrahamic religions.

[2] As described by theorist and quantum physicist, Karen Barad, in her 2011 essay, “Nature’s Queer Performativity.”

[3] The phrase “tentacular critters” is used by theorist Donna J. Haraway in her 2016 book, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene.

[4] Text from Morehshin Allahyari’s website for the She Who Sees The Unknown project, last visited 16 November 2023.