Between Hype Cycles and the Present Shock

This essay is an attempt to understand if, and how, art can exist in the present time. No more, no less. I’m, of course, aware that my intellectual powers may not be enough for such an undertaking; that’s why I’m asking so many thinkers who are stronger than me for help. But neither them, nor myself will be able to answer most of the questions I’m raising here. Nevertheless, I think it’s important to raise them. Although I’m sure most people are aware of the problems I’ll discuss, nobody really seems to bring them to their logical ending, and wonder: is it still possible to make art under these conditions? Is it still possible to experience art as it should? What’s the price we have to pay for engaging today’s media and the crucial issues of our time, in terms of duration and long term appreciation? We know we are living in an age that is profoundly different from that in which contemporary art was born: an age of acceleration, present shock, distracted gaze and end of the future. And yet, when it comes to art, we still confront it as if nothing had actually changed: as if it were the sacred result of moments of deep focus and concentration; as if it could still be experienced without distraction; as if it were the expression of a constant fight against the old, and of an endless rush towards the new; as if it could speak a universal language, and last forever. But it doesn’t.

The considerations that follow apply to all contemporary art. However, I use contemporary media art as the main area of reference, as I think most of the problems I’m outlining are more visible there, and more radically affecting the art that uses the tools and addresses the key issues of the post digital age.

Time Traveling

To really see how much art has changed along the last fifty years, we should look at it through the eyes of somebody who fell asleep in the Seventies, and woke up in 2019. So, let’s bring this time traveler to the opening of the latest Venice Biennale, May You Live in Interesting Times. We arrive in Venice on May 9th, on the second of the pre-opening days, for invited professionals and the press. Besides the main exhibition, my Instagram feed already suggested a couple of events that could not be missed. The Lithuanian Pavilion is on everybody’s mouth. An online magazine just published an article, in which a respected writer and curator claims that it would deserve the Golden Lion; and many seem to agree with him, if we judge from the amount of pictures and videos circulating online and depicting this peaceful summer beach seen from above. Installed at the Circolo Ufficiali Marina Militare, Sun & Sea (Marina) is the collaborative effort of three young female artists based in Vilnius: filmmaker and theatre director Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė (born 1983); writer, playwright, and poet Vaiva Grainytė (born 1984); and artist, musician and composer Lina Lapelytė (born 1984). Sun & Sea (Marina) is the second collaboration for the three artists, who envisioned a scene in which a number of participants in bright bathing suits perform the lazy, slow gestures of a summer afternoon at the seaside, seemingly unaware of the gaze of dozens of spectators looking at them from a balcony. The sand has been brought by trucks from the Northern Sea, and is skillfully lightened by a number of invisible artificial lights simulating the northern sun. Various songs are sung by the performers of this self-described “opera performance:” “everyday songs, songs of worry and of boredom, songs of almost nothing. And below them: the slow creaking of an exhausted Earth, a gasp.” Few days after Sun & Sea (Marina) would win the Golden Lion.

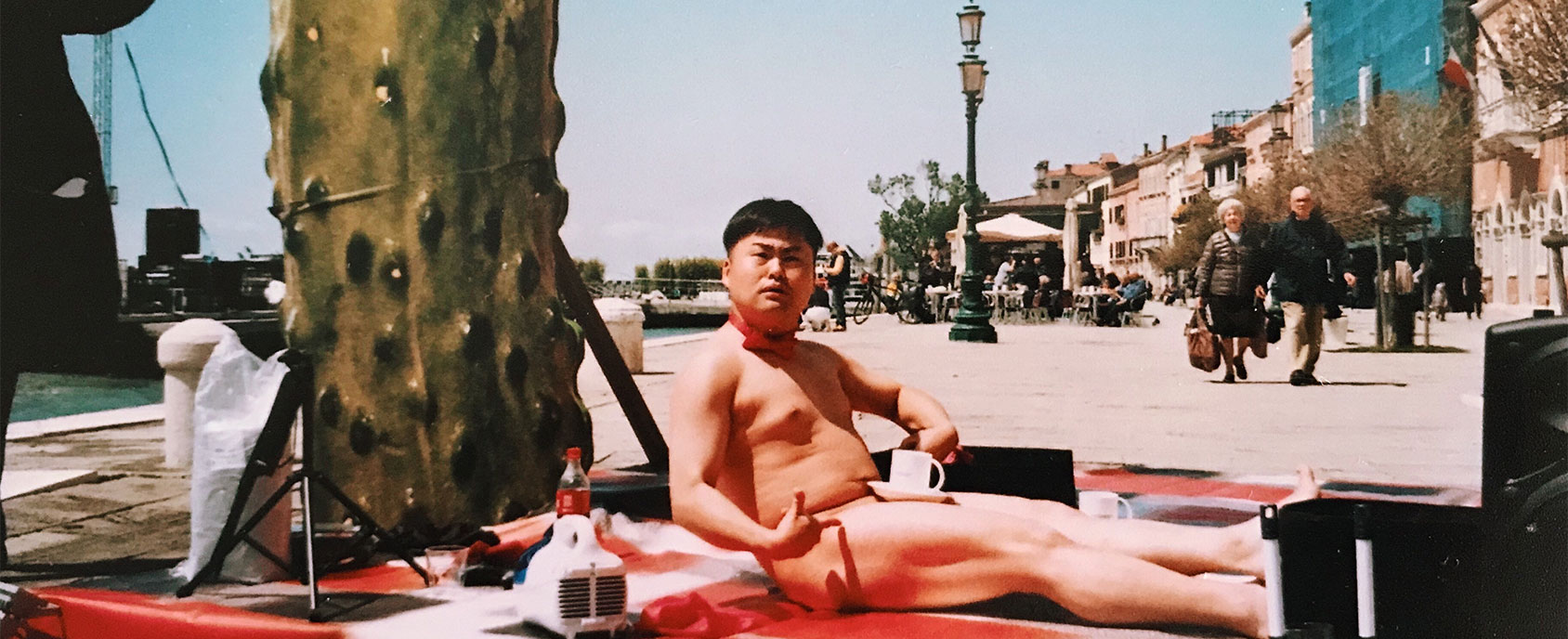

The second event looks very different, yet equally attractive. It’s called The New Circus Event, and has been organized by the collective Alterazioni Video, with the support of the V-A-C Foundation, a newborn Russian institution (founded in Moscow in 2009) which in 2017 opened its headquarters in Venice, at Zattere. There, for the opening of a new exhibition, Alterazioni Video set up a three days outdoor event. I’ve been following them for years, and I love their ability to involve a growing community of friends, thinkers and artists from all fields to generate hardcore entertainment. Their work often deals with subcultures, from global online communities to local tribes and habits, and the visual language they produce. As I see the first pictures of their circus, I think I can’t miss it (in fact I missed it, and together with Sun & Sea (Marina) it was the main reason for my FOMO during the opening of the Biennale). But in the fiction of this short tale, I’m bringing a time traveller from the Seventies to witness this crazy event, in which freakshows, street performers and home performers from all over the world, often cultivating their large global audiences through their social media accounts, perform in front of trashy, colorful sets, full of gradients, junk shop furniture, and giant reproductions of cucumbers, photoshopped faces and animals on shaped wooden panels.

What would our time wanderer learn from these two works, about our world, the contemporary art world and the current status of art? An easy guess is that the world has become a global environment, and art has changed accordingly. The iron curtain is down, the decolonization process has been completed, and countries which didn’t even have a Pavilion at the Giardini—let alone an artistic practice recognizable as contemporary art—are now important players in a globalized art world.

Some steps have been taken toward the end of the Western, as well as of the male dominance in art: the Golden Lion was not won by a white male caucasian, but by three young Lithuanian women (other prizes went to an Afro-american male artist, a Greek female artist, a Nigerian female artist, a Mexican female artist, while the career prize was won by Jimmie Durham, an American artist with American Indian roots).

Both works demonstrate the end of the segregation between high- and lowbrow culture, avant garde and kitsch: Sun & Sea (Marina) celebrates a popular, democratic ritual and reveals a series of references to pop culture artifacts; The New Circus Event playfully appropriates and exploits the lowbrow with an anthropological attitude, underlying the uncomfortable proximity between social media exhibitionism and performance art.

Alterazioni Video, The New Circus Event, 2019. Courtesy the artists.

Although the art world still is the framework in which artworks are presented, its role as a legitimization system seems to have weakened. It’s hard to say whether the audience popularity of the Lithuanian pavilion played a role in the jury verdict or not; what’s easy to see is that the Golden Lion for the Best National Pavilion was won by three young artists from different fields, at their second collaboration together, with no art world pedigree, no museum show, no collaboration with powerful commercial galleries.

Performance art, a nascent, radical art form in the Seventies, seems to have become pretty mainstream. Moreover, art is no more the subject of contemplation, but of experience; and the experience of art itself is performative. This is a process my time traveller can understand, as it started with the avant gardes and it was revamped by his generation; now he can witness the triumph of the performative—of art as experience, facilitated by the information infrastructure and media of the Twenty-first century. According to Boris Groys, contemporary art cannot—and does not—produce artworks: “Rather, it produces artistic events, performances, temporary exhibitions that demonstrate the transitory character of the present order of things and the rules that govern contemporary social behaviour.”

As French philosopher Yves Michaud claimed years ago in another great book about contemporary art: “At the very foundation of contemporary art lies a dual logic. On the one hand, art takes the dispersed and weightless shape of the aesthetic experience I described, even if in contexts that are still conventional and institutional (gallery, museum, art school, artistic event). This is the vaporization of art. On the other hand, we see an aestheticization of experience in general: beauty has no limits […] Art is everywhere and so nowhere. This is the aestheticized experience.”

Furthermore, mediation has become a consistent part of the experience of art, on a double level. On the one hand, if we can’t attend an event, the only way we have to access it is through documentation: when art is intrinsically performative and vaporized, if we don’t experience it in the “here and now,” documentation is the only possible alternative. Groys goes even further, claiming that documentation is the shape an artistic event takes after its manifestation—the way it is preserved and turned into a museum item: “Today’s artistic events cannot be preserved and contemplated like traditional artworks. However, they can be documented, ‘covered’, narrated and commented on. Traditional art produced art objects. Contemporary art produces information about art events. That makes contemporary art compatible with the Internet.”

Andrey Karlov’s assassination, 19th December 2016. Photo © Yavuz Alatan—AFP/Getty Images

According to Groys, transforming artistic documentation into art is the main mission of the contemporary art museum. On the other hand, documenting is one of the main things we do when we experience art—becoming a consistent part of the art experience itself. In the age of sharing, experiencing art has become a ritual that needs to be documented. Equipped with a good camera, the smartphone in our pocket is our third eye, that we constantly use to take pictures, short videos, selfies, and to share them instantly with our friends. Then, the time we can invest in the experience of that given piece expires, and we move over.

Artists know about this new way to experience artworks, and instead of fighting against it, they encourage it by designing their works accordingly. Sun & Sea (Marina) is apparently a time based experience involving all our senses: as an opera, it’s based on a “libretto,” it has a beginning and an end. Yet, the way the experience was envisioned—placing viewers on a balcony and carefully enlightening the scenes—belongs to theater as much as to the photographer studio. The beach is arranged to look good in pictures, to proliferate through pictures. Dissemination through social media is embedded into the piece. The same can be said for The New Circus Event, whose set design is made to force our point of view and to help us generate colorful pictures that could travel virally. I explain to my time traveller that both works pay tribute to the visual strategies of an “art movement” that, after a worldwide success and a fierce debate, was declared dead somewhere in 2016—the post internet. We will get back to it later on.

Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, Lina Lapelytė, Sun & Sea (Marina), 2019. Photo by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, courtesy Wikipedia.

Meanwhile, what’s important to note is how this inclusion of documentation in the experience of art belongs to a new regime of attention, in Michaud’s words “where the deep reading and interpretation of art works is replaced by fast scanning.” The emergence of this relational approach to art—as a way to generate images and get likes, show your friends where you are, demonstrate your belonging to a community, keep a personal diary of your extraordinary life—enforces the process that Michaud described—in a pre- social media era—as the end of the “focused gaze” and the triumph of the “distracted gaze.” Something that would happen anyway, as we are all floating in a perpetual flow of information and message notifications.

And if this happens when the art is present, in a dedicated space designed to bring all attention to the artwork, how focused can the gaze of the viewer that experiences art online—be it the actual piece (a video, a net-based artwork) or its documentation be? In the attention economy of the internet, art dissolves within a universal flow of information, and has to compete with anything from information to flirting, from mainstream entertainment to cute cat videos, from memes to porn. Groys: “the so-called content providers often complain that their artistic production drowns in the sea of data that circulates through the Internet and, thus, remain invisible.”

How can an artist be happy with it, and even encourage it?—my time traveller wonders. I try to explain to him the schizophrenia of our age, where artworks are simultaneously competing for our attention and inviting us to take pictures. By visiting the main exhibition at the Arsenale, he already noticed that what he still calls “video art” has evolved into a multi-sensory immersive experience, with huge screens, spatialized sound, props, even scents and vibrations that could be experienced physically. Amazing experience, let’s take a picture.

Groys comes in handy, again “The Internet allows the author to make his or her art accessible to almost everyone around the world and at the same time to create a personal archive of it. Thus, the Internet leads to the globalization of the author, of the person of the author. […] Traditionally, the reputation of an author—be it writer or artist—moved from local to global. One had to become known locally first to be able to establish oneself globally later. Today, one starts with self-globalization.”

In other words, self-distribution—and a way of designing the work that demands the participation of the spectator (that can be better described as a consumer-producer, or prosumer)—allows the artwork to reach a global audience, with or without the help of the art world. And yet, “Even if all data on the internet is globally accessible, in practice the internet leads not to the emergence of a universal public space but to a tribalization of the public. The reason for that is very simple. The internet reacts to the user’s questions, to the user’s clicks. The user finds on the internet only what he or she wants to find.”

Welcome to the filter bubble!—I joke with my time traveller. To make him even more confused, I tell him that this effort toward the “globalization of the author” has another side effect: the end of the distance between art production and exhibition. Groys again: “The emergence of the Internet erased this difference between the production and exhibition of art. The process of art production as far as it involves the use of the Internet is already exposed from beginning to end. Earlier, only industrial workers operated under the gaze of others, under the permanent control that was so eloquently described by Michel Foucault. Writers or artists worked in seclusion—beyond that panoptic, public control. However, if the so-called creative worker uses the Internet, he or she is subjected to the same or an even greater degree of surveillance as the Foucauldian worker.”

Art has become a shared experience not only at the level of exhibition, but also at the level of production. This allows me to remind my time traveller that the crisis of focus we discussed on the level of the audience finds its counterpart in the creative process. Just like everybody else, while working (often in front of their computer) artists make a fragmented experience of time: they have many programs and tabs open, are distracted by notifications, and often stop working to live stream their activity. How can art still be, as it was often conceived in the past, the output of an internal labour and a never ending effort to find within yourself your own way to see the world, your own language and poetics?

Waiting for the Tsunami

Another feature shared by Sun & Sea (Marina) and The New Circus Event is on the level of content. They both picture a world with no future. In Sun & Sea (Marina), the awareness of the coming apocalypse generates the arcadian dream of a humanity enjoying the last, already dangerous rays of sun and awaiting the end by taking care of herself quietly, in calm resignation. Through the songs of the opera performance, “Frivolous micro-stories slowly give rise to broader, more serious topics and grow into a global symphony, a universal human choir addressing planetary-scale, anthropogenic climate change. In the work, the physical finitude and fatigue of the human body becomes a metonym for an exhausted Earth. The setting—a crowded beach in summer—paints an image of laziness and lightness. In this context, the message follows suit: serious topics unfold easily, softly—like a pop song on the very last day on Earth.”

The New Circus Event, on the other hand, was subtitled Waiting for the Tsunami, a handle that was systematically used by Alterazioni Video as an hashtag on social networks. The subtitle comes from an older project by them, a failed web TV show they tried to perform in 2006, which wanted to demonstrate the “present situation of communication, with the opportunities offered by the new media and their possible influences on contemporary art.” The New Circus Event relates to this old work for its attempt to create a palimpsest, a spectacle streamed from social media and materialized on Zattere; but it also points to the Dionysian dimension of the circus, and to hardcore entertainment as what remains to us under the threat of the impending tragedy.

What happened to the future?—my time traveller wonders. Back in the Seventies, the future still existed: it was the place where people projected their dreams of social renovation and progress. In art, Modernism was grounded in the idea of constant innovation and progress—and those who took the first steps into the future were called, unsurprisingly, avant gardes. And then, there was technological innovation that made this process faster. In 1970, futurist Alvin Toffler published a book called Future Shock, in which he claimed that change was happening so fast that people could not even adapt to it. In 1972, the book was turned into a documentary film, with Orson Welles as on-screen narrator. In one of the fist scenes, he says: “we live in an age of anxiety and time of stress and with all our sophistication we are in fact the victims of our own technological strength; we are the victims of shock, of future shock. Future shock is a sickness which comes from too much change in too short a time; it’s the feeling that nothing is permanent anymore; it’s the reaction to change that happens so fast that we can’t absorb it; it’s the premature arrival of the future. For those who are unprepared its effects can be pretty devastating.”

Toffler’s contradictory futurism anticipated both the dreams of innovation and progress of the techno utopians, and—with his awareness of the devastating consequences of too much acceleration—the dystopian vision of the future that would have been introduced, in a few years, by the cyberpunk movement in literature. The first trend was kept alive until the end of the century by the promises of the neoliberal economy—which, after the fall of the Soviet Union, seemed to be the only political and economic model available; by the speed of technological innovation, that seemed to confirm the truth of the Moore’s law; and by the hopes and anxieties related to the turn of the millennium. In 1999 another futurist, Ray Kurzweil, published a book called The Age of Spiritual Machines, in which he introduced his “Law of Accelerating Returns,” according to which the rate of change in technological systems tends to increase exponentially, turning the linear development embedded in our traditional idea of progress into an exponential curve. A Moore’s law on steroids.

Along the same years, Postmodernist theory was putting the idea of linear progress and future itself into question. It would be impossible to resume the complexities and nuances of Postmodernist theory here—although actually most of the things we wrote above find their roots in there. But that the end of the future is one of the distinctive features of Postmodernism can be easily proved by quoting the very first lines of Fredric Jameson’s seminal essay Postmodernism, Or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1984): “The last few years have been marked by an inverted millenarianism in which premonitions of the future, catastrophic or redemptive, have been replaced by senses of the end of this or that (the end of ideology, art, or social class; the ‘crisis’ of Leninism, social democracy, or the welfare state, etc., etc.); taken together, all these perhaps constitute what is increasingly called postmodernism.”

In art criticism, already in 1979 Achille Bonito Oliva celebrated the movement he christened Transavantgarde suggesting the reversal of the “Darwinistic and evolutionary mentality of the Avant garde” as its main quality. Against a (modernist) idea of art as a “continuous, progressive and straight line,” that produced the “compulsion to the new” of the Neo Avant gardes of the Sixties, Bonito Oliva championed an idea of art grounded on a circular time, in which “the scandal, paradoxically, consists in the lack of novelty, in art’s capacity to have a biological breathing, made of accelerations and slowdowns.”

Futurism and Net.art

Emerged in the mid Nineties, with the rise of the web browser and the massive access to personal computers and the internet, net.art embodies the contradictions of this moment as no other art form of the Twentieth century could do. It appeared as a reaction to the commodification of art in the late Eighties and the Nineties, when art galleries and collectors emerged as the guiding forces of an art world with no directions, and to the predatory attitude with which they approached the emerging art markets in Eastern Europe. By refusing the art object and choosing to operate on a distributed communication platform, net.art was digging its own free space—producing an art that was dematerialized, accessible and didn’t require the mediation of anything or anybody to be brought to an audience: no galleries, no institutions, no curators.

It reconnected to the anti-art tradition of the Avant gardes as it was inherited and developed by Situationism, Neoism and other subcultural movements of the early Nineties. It played the Avantgarde, picking its own name, forging its own original myth and narrative, bypassing the art world and creating its own platforms of networking and debate, even connecting with the emerging community of online activism and tactical media. Although aware that the modernist utopia was impossible to bring back, it found in the early internet a Temporary Autonomous Zone in which the Avantgarde could be set up as a Pirate Utopia for a number of years.

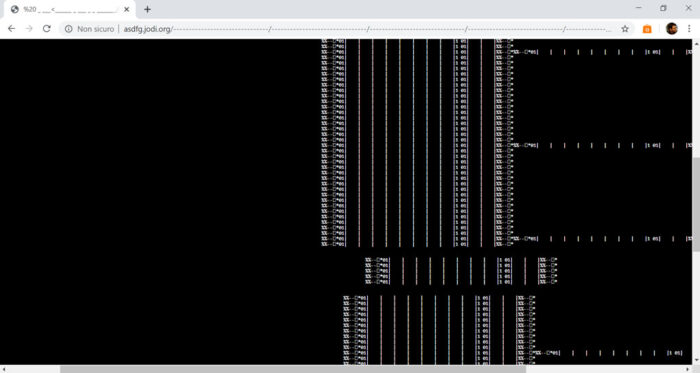

JODI (Joan Heemskerk, Dirk Paesmans), ASDFG. Screenshot, http://asdfg.jodi.org/

An Avantgarde that came after Postmodernism, net.art embodied another contradiction: it believed in the emancipatory power of the technology it relied upon without identifying with the techno-utopianism of Silicon Valley. The ideas of Ted Kaczynski, the Unabomber, were an early reference for net.art; and JODI (Dirk Paesmans and Joan Heemskerk), in their interviews, underlined how experiencing the ideas and motivations of software designers in the Silicon Valley, brought them to develop their subversive approach to software and interfaces: “The technique to create confusion and to mix things up has been used often before, but with this specific medium we made an early start. A reason for this is that we left the Netherlands on our own for San Jose, California. Silicon Valley. We went there to see how all this Apple stuff and all software and applications, Photoshop, Macromind, Netscape ‘live’ there. What kind of people make this. This is very interesting to us. In some way we feel very involved, it is a bit of a personal matter to turn Netscape inside out for instance. I have a picture in my mind of the people that make it. And not just how they make it, but also […] how they see their Internet. ‘Their’ Internet, you can say that for sure.”

“It is obvious that our work fights against high tech. We also battle with the computer on a graphical level. The computer presents itself as a desktop, with a trash can on the right and pull down menus (sic!) and all the system icons. We explore the computer from inside, and mirror this on the net.” net.art embodies the precarious futurism of the late Twentieth Century inasmuch it believes in its own ability to participate in shaping the techno-social infrastructure of the internet and influencing its ecology: by hacking, subverting or inventing tools, by inventing strategies of resistance, criticism and subversion and by fighting against corporate or institutional subjects on a peer to peer level, only relying upon its knowledge of the medium and its attitude at networking.

The End of the Future

…and the Present Shock

Anticipated in the late Twentieth Century by postmodernist theory and the near future dystopias of cyberpunk literature, the end of the future has turned in the early Twenty-first Century into a widespread, popular if not even mainstream, idea. The future, of course, doesn’t exist if not as the result of a projection, of an imagination effort: so, what’s over is not the future per se, but either our ability to imagine a possible future or a future as something different from an ever changing, yet never evolving present. According to the first perspective, the idea of the future is turned off by an impending apocalyptic ending; according to the second, the idea of the future is turned off by the awareness that nothing will change, that everything will always be the same.

Nothing new under the sun, one may say. Both the upcoming apocalypses and the impossibility of change are philosophical concepts that have been around since the beginning of human civilization. The difference, today, is that on the one hand, science and technology—the only systems of thought we seem to believe in—are either confirming or even pushing for an apocalyptic ending; and that, on the other hand, we have become incapable to imagine a socio-political order that could offer an alternative to the present one.

Let’s briefly consider the two main forms the idea of the apocalypse has taken in recent years: climate change and the technological singularity. Climate change is the consequence of the way we have been abusing the natural resources of our planet along our industrial and post-industrial past. We are all aware of it: the ozone hole, the melting permafrost, the rising oceans, etc. etc. The news, brought to us by scientists, is that if we don’t take drastic measures to change this trend on a global level, we would be reaching very fast the moment in which this process would become irreversible, generating conditions that would make human life on the Planet Earth impossible, or very hard. And of course, we are not doing enough. In October 2018, The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—founded in 1988 by the United Nations Environment Programme (UN Environment) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO)—released a report saying that we will be able to keep global warming below 1.5°C above pre-industrial level only for another twelve years. The report outlines what we should do, on a global level, to stop global warming, and explains the consequences of this process on a short and long term; however, on the level of politics, nobody really seems to care about it.

Climate Strike protest, Westminster, London, 20 September 2019. Photo CC Julian Stallabrass

Nonetheless, the younger generations are starting to care. In August 2018, Swedish school girl Greta Thunberg organized a school strike for the climate outside of the Swedish parliament, saying she would have kept striking every Friday until her country would align to the Paris Agreement. In a few months, her “Fridays for Future” initiative evolved into a global movement with the organization of two Global Climate Strikes, on March 15, 2019 and May 24, 2019. On a local level, thousands of climate strikes have been organized locally all over the world. The “About Us” text on the Climate Strike website reads: “The adult generations have promised to stop the climate crisis, but they have skipped their homework year after year. Climate strike is a wake-up call to our own generation. And it is the start of a network that will solve the greatest challenge in human history. Together. We need your hands and hearts and smarts!”

Although the rise of a protest movement and a call to action always reveals the faith that your action may have an impact, the Climate Strike is a weird mix of hope and hopelessness, as it can be easily seen in their claims, where “We will get the future we want!” goes hand in hand with “You are melting our future,” “Don’t burn my future,” “There will be no future,” “Why do we need GCSEs if we have no future?,” “System change no climate change.”

If compared with the urgency and reality of global warming, the technological singularity may sound like a more remote perspective, closer to the dreams or nightmares of a science fiction writer than to a possible near future option. What suggests to include it in this list of apocalyptic futures is, on the one hand, the fact that the technological singularity is embedded in the idea of the future of most techno-utopians, who are also the same people who are shaping the current technology. It’s, in other words, the built-in ideology behind most of today’s technological systems and devices. On the other hand, the fact that we are already building self-improving machines that we can’t understand. In his book New Dark Age (subtitled: Technology and the End of the Future), artist and theorist James Bridle enumerates Isaac Asimov’s famous three laws of robotics, adding: “To these we might add a fourth: a robot—or any other intelligent machine—must be able to explain itself to humans. Such a law must intervene before the others, because it takes the form not of an injunction to the other, but of an ethic. The fact that this law has—by our own design and inevitably—already been broken, leads inescapably to the conclusion that so will the others. We face a world, not in the future but right now, where we do not understand our own creations. The result of such opacity is always and inevitably violence.”

In short, the technological singularity “is a hypothetical future point in time at which technological growth becomes uncontrollable and irreversible, resulting in unfathomable changes to human civilization.” Whatever good or bad will be these changes for humanity, they will be out of our control. According to Murray Shanahan: “If the intellect becomes, not only the producer, but also a product of technology, then a feedback cycle with unpredictable and potentially explosive consequences can result. For when the thing being engineered is intelligence itself, the very thing doing the engineering, it can set to work improving itself. Before long, according to the singularity hypothesis, the ordinary human is removed from the loop, overtaken by artificially intelligent machines or by cognitively enhanced biological intelligence and unable to keep pace.”

Both climate change and the technological singularity are the result of processes we started off and we feel unable to stop. The Climate Strike claims for a “system change.” Yet, is a system change actually possible? In Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternatives? (2009), British cultural theorist Mark Fisher takes off from this very question, and from the postmodernist idea, attributed to Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Žižek, that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism: “That slogan captures precisely what I mean by ‘capitalist realism’: the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it.”

While recognizing his debt toward Jameson, Fisher suggests to replace postmodernism with Capitalism Realism for three main reasons: “Ultimately, there are three reasons that I prefer the term capitalist realism to postmodernism. In the 1980s, when Jameson first advanced his thesis about postmodernism, there were still, in name at least, political alternatives to capitalism. What we are dealing with now, however, is a deeper, far more pervasive, sense of exhaustion, of cultural and political sterility […] Secondly, postmodernism involved some relationship to modernism […] Capitalist realism no longer stages this kind of confrontation with modernism. On the contrary, it takes the vanquishing of modernism for granted: modernism is now something that can periodically return, but only as a frozen aesthetic style, never as an ideal for living. Thirdly, […] in the 1960s and 1970s, capitalism had to face the problem of how to contain and absorb energies from outside. It now, in fact, has the opposite problem; having ail-too successfully incorporated externality, how can it function without an outside it can colonize and appropriate? For most people under twenty in Europe and North America, the lack of alternatives to capitalism is no longer even an issue. Capitalism seamlessly occupies the horizons of the thinkable […] now, the fact that capitalism has colonized the dreaming life of the population is so taken for granted that it is no longer worthy of comment […] the old struggle between detournement and recuperation, between subversion and incorporation, seems to have been played out. What we are dealing with now is not the incorporation of materials that previously seemed to possess subversive potentials, but instead, their precorporation: the pre-emptive formatting and shaping of desires, aspirations and hopes by capitalist culture […] ‘Alternative’ and ‘independent’ don’t designate something outside mainstream culture; rather, they are styles, in fact the dominant styles, within the mainstream.”

We will get back to these ideas about styles and the “precorporation” of alternatives later on. By now, it’s enough to notice that this long quote testifies of a moment in which a future different from the present cannot be imagined, not even dreamt. This, of course, brings to impotence, immobilization and depression, topics at the core of Capitalist Realism.

One may argue that this lack of perspective doesn’t belong to everybody in the Twenty-first Century. Movements like the anti-globalization movement and Occupy Wall Street prove that we are still able to revolt against the present and imagine the future. So, why weren’t they able to change things? In 2011, Franco “Bifo” Berardi tried to answer this question with his book After the Future. According to Bifo, “the answer is not to be found in the political strategy of the struggle, but in the structural weakness of the social fabric. During the twentieth century, social struggle could change things in a collective and conscious way because industrial workers could maintain solidarity and unity in daily life, and so could fight and win. Autonomy was the condition of victory […] When social recomposition is possible, so is collective conscious change. […] That seems to be over. The organization of labor has been fragmented by the new technology, and workers’ solidarity has been broken at its roots. The labor market has been globalized, but the political organization of the workers has not. The infosphere has dramatically changed and accelerated, and this is jeopardizing the very possibility of communication, empathy and solidarity. In the new conditions of labor and communication lies our present inability to create a common ground of understanding and a common action.”

That’s why the activist movements of the Twenty-first Century remained ethical movements, without evolving into social transformers. That’s why we feel immobilized and depressed. In this condition, if we can’t fight against capitalism, we can still at least phantasize about its self destruction. This is, in short, what the accelerationist left wants to do: bring neoliberal capitalism to collapse by accelerating it. Both in the #ACCELERATE Manifesto (2013) and in its more elaborate sequel, the book Inventing the Future. Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (2015), Nick Srniceck & Alex Williams give us back the future as something that should be “invented,” “constructed,” even “demanded.” The inevitable premise is that it isn’t among us anymore. As they write at the end of the “Manifesto:” “24. The future needs to be constructed. It has been demolished by neoliberal capitalism and reduced to a cut-price promise of greater inequality, conflict, and chaos. This collapse in the idea of the future is symptomatic of the regressive historical status of our age, rather than, as cynics across the political spectrum would have us believe, a sign of sceptical maturity. What accelerationism pushes towards is a future that is more modern—an alternative modernity that neoliberalism is inherently unable to generate. The future must be cracked open once again, unfastening our horizons towards the universal possibilities of the Outside.”

The introduction of Inventing the Future is even more explicit: “Where did the future go? For much of the twentieth century, the future held sway over our dreams […] Today, on one level, these dreams appear closer than ever […] Yet […] the glimmers of a better future are trampled and forgotten under the pressures of an increasingly precarious and demanding world. And each day, we return to work as normal: exhausted, anxious, stressed and frustrated. […] In this paralysis of the political imaginary, the future has been cancelled.”

Joshua Citarella, Compression Artifacts, 2013. Built in an undisclosed location. Featuring works by Wyatt Niehaus, Kate Steciw, Brad Troemel, Artie Vierkant and Joshua Citarella. Image courtesy the artist.

This is our present. A New Dark Age, in James Bridle’s words, in which “that which was intended to enlighten the world in practice darkens it. The abundance of information and the plurality of worldviews now accessible to us through the internet are not producing a coherent consensus reality, but one riven by fundamentalist insistence on simplistic narratives, conspiracy theories, and post-factual politics. It is on this contradiction that the idea of a new dark age turns: an age in which the value we have placed upon knowledge is destroyed by the abundance of that profitable commodity, and in which we look about ourselves in search of new ways to understand the world.”

An age in which we may even indulge, as Eugene Thacker did in his book In the Dust of This Planet (2011), in the philosophical idea of a “world-without-us.” According to Thacker, either through mythology, theology or existentialism, we have always been thinking the world as a world “for us.” Although we may think, in abstract, to a “world-in-itself,” our anthropocentric view makes it a paradoxical concept: “the moment we think it and attempt to act on it, it ceases to be the world-in-itself and becomes the world-for-us.” Yet today, thanks to the global warming and the predictive models we developed to study it, a future possible “world-without-us” has become thinkable, and this, for the first time in human history, allows us to think the world-in-itself.

Yet, the end of the future is not just the consequence of the impending apocalypses, or of our difficulties in imagining a new social order; the present itself has become so bulky today to fill up our gaze, and prevent us to see what’s beyond it. In 1970, to describe the impact of change and of the speed of technological evolution, Alvin Toffler introduced the concept of “future shock,” a cultural shock that didn’t come out of the meeting with the radically Other, but with our own accelerated future. In 2004, media theorist Douglas Rushkoff introduced the concept of “present shock” to suggest that, in the Twenty-first century, shock is not generated by the speed of change, but rather by a present that doesn’t leave us any chance to look beyond it. “Our society has reoriented itself to the present moment. Everything is live, real time, and always on. It’s not a mere speeding up, however much our lifestyles and technologies have accelerated the rate at which we attempt to do things. It’s more of a diminishment of anything that isn’t happening right now, and the onslaught of everything that supposedly is […] If the end of the twentieth century can be characterized by futurism, the twenty-first can be defined by presentism […] We tend to exist in a distracted present… Instead of finding a stable foothold in the here and now, we end up reacting to the ever-present assault of simultaneous impulses and commands.”

Rushkoff’s idea of the present shock takes off from the Postmodernist notion of the end of the linear narratives, traditional plots and grand narratives (what he calls “narrative collapse”) and also includes “the way a seemingly infinite present makes us long for endings” (that is, the apocalyptic views we have been discussing before); but it gets more original when he explores the three main characters of the present shock, all of them somehow related to our experience of time: “Digifrenia,” that is the technological bias that forces us to be in different places at the same time; “Overwinding,” that he describes as “the effort to squish big timescales into much smaller ones”; and “Fractalnoia,” “the desperate grasp for real-time pattern recognition.”

Running here and there while endlessly sharing our feelings, our position, and our life; moving from one tab to the other, from one task to the other, from one device to the other; overlapping work time and free time to the extent we can’t distinguish between the two anymore; always trying to find an order and a ratio in the constant flow of information we are dealing with—how can we find the time to look forward and think about what’s coming next? How can we, to go back to art, find the time, the focus, the deep level of immersion and concentration to experience or make art?

Presentism and Post Internet

The term Post internet started being used by artist and curator Marisa Olson around 2008 to describe her art and that of her peers: a practice that was not medium specific and happening only online, but that was using the fragments of a compulsory web surfing to produce online pieces as well as performances, animations, installations, songs, photos, texts etc. Other terms used were “art after the internet” (Olson 2006) and “Internet Aware Art” (Guthrie Lonergan 2008).

At that time, the Internet had survived the collapse of the so-called new economy, and it was structurally evolving into what in 2004 started to be called Web 2.0: a web “that emphasizes user-generated content, ease of use, participatory culture and interoperability (i.e., compatible with other products, systems, and devices) for end users.” Google was emerging as the main entrance door to the contents of the internet, thanks to its search algorithm; and was already evolving into a giant corporation able to control almost every aspect of our online presence, thanks to its email service, its free blogging platform, and YouTube (founded in 2005 and bought by Google in October 2006). Social networking was emerging, too.

If, in the late Nineties, the internet was perceived by artists as a free communication space to colonize and shape, where you could invent your own language and design your own place, now it was gradually evolving into a mainstream mass medium open to everybody, and a plain mirror of the real world. Artists started gathering in “surfing clubs,” group blogs where they collected, remixed and shared the results of their daily surfing experience; instead of learning to hack and inventing their own language, they preferred to use commercial, off-the-shelves softwares in their default settings; instead of seeing their practice as a way to escape the art world and get in touch with audiences without mediation and outside of the existing power structures, they were naturally translating their online experience into forms that would easily fit in an exhibition space.

If early net.art was a futurist Avantgarde, post internet was a presentist art movement, as art writer Gene McHugh acutely noticed already in 2011: “On some general level, the rise of social networking and the professionalization of web design reduced the technical nature of network computing, shifting the Internet from a specialized world for nerds and the technologically-minded, to a mainstream world for nerds, the technologically-minded and grandmas and sports fans and business people and painters and everyone else. Here comes everybody. Furthermore, any hope for the Internet to make things easier, to reduce the anxiety of my existence, was simply over—it failed—and it was just another thing to deal with. What we mean when we say ‘Internet’ became not a thing in the world to escape into, but rather the world one sought escape from… sigh… It became the place where business was conducted, and bills were paid. It became the place where people tracked you down.”

Young post internet artists were not the only ones realizing that Web 2.0, social media, wi-fi connections and, since 2007, smartphones were changing our relationship with technology on a mass scale and on a global level. Artists like Cory Arcangel, a bridge between the early net.art and the post internet generation, and Ryan Trecartin were starting getting recognized in the art world; artists—and later on, critics and curators—with an art world reputation, like Seth Price, David Joselit, and Hans Ulrich Obrist, were getting interested in topics such as the online circulation of images and artworks and the generational shift.

In September 2012, on an issue of Artforum focused on “Art’s new media,” art critic Claire Bishop published an article called Digital Divide, in which she wondered: “So why do I have a sense that the appearance and content of contemporary art have been curiously unresponsive to the total upheaval in our labor and leisure inaugurated by the digital revolution? While many artists use digital technology, how many really confront the question of what it means to think, see, and filter affect through the digital? How many thematize this, or reflect deeply on how we experience, and are altered by, the digitization of our existence?” At the time, it wasn’t easy to understand that she was not simply speaking for herself, but giving voice to an urgent need of the whole art world: to see more art responding to a shift that was finally perceived by everybody as part of their daily life.

Post internet was there, ready to answer these urgent questions. What happened along the following years, mostly between 2013 and 2016, was something unprecedented in recent art history: a movement originated in the relatively small niche of media art became an art world trend with support from both the institutions and the art market. In a few years, artists like Oliver Laric, Jon Rafman, Aleksandra Domanovic, Petra Cortright, Parker Ito, Constant Dullaart, Katja Novitskova, Cécile B. Evans, Artie Vierkant, to name only a few, got the attention of the mainstream art world, together with other artists not connected to the “surfing clubs” generation but still very close to them for topics, formal solutions and personal networks, such as Simon Denny, Trevor Paglen, Ed Atkins and Hito Steyerl.

Untitled (Not in the Berlin Biennale), 2016; © Roe Ethridge, Chris Kraus, Babak Radboy; image from Not in the Berlin Biennale; photography Roe Ethridge; special thanks to Andrew Kreps; Capitain Petzel, Berlin

While coming to prominence, Post internet started to suffer some commercial dynamics of the mainstream art world. What was easy to repeat and imitate, in Post internet—the use of painterly effects mediated by software, the reference to interface aesthetics and online subcultures such as vaporwave, the research around online circulation of images, from memes to stock imagery—became a style and got imitated by anybody who wanted to look fashionable and up to date. On a parallel path, some Post internet artists—like Petra Cortright and Parker Ito—started being sold on auctions, and were included in the wave of the so-called Zombie Formalism. The term, coined by critic Walter Robinson in 2014, refers to a wave of abstract formalist paintings, made by a bunch of young artists supported by collectors known as art flippers for their investment strategies—they buy artworks from the artists at relatively low prices and put them back at auctions soon afterward. Robinson explained the label this way: “‘Formalism’ because this art involves a straightforward, reductive, essentialist method of making a painting (yes, I admit it, I’m hung up on painting), and ‘Zombie’ because it brings back to life the discarded aesthetics of Clement Greenberg, the man who championed Jackson Pollock, Morris Louis, and Frank Stella’s ‘black paintings’ among other things.”

The prices reached on auction by these artworks, together with their visual qualities—a pleasant, recognizable abstraction easy to like on social networks—made Zombie Formalism a successful movement in the art world… at least for some years. As many outcomes of financial speculations and inflated expectations, Zombie Formalism collapsed upon itself, and only a few artists were able to keep up and survive “the Zombie Formalism Apocalypse,” as a 2018 Artnet News article put it.

Between 2014 and 2015, Post internet was everywhere, and many in the art world started being fed up with it. In October 2014, art critic Brian Droitcour published on Art in America an article which, under the headline The Perils of Post Internet Art, offered this critical definition: “Post-Internet art does to art what porn does to sex—renders it lurid. The definition I’d like to propose underscores this transactional sensibility: I know Post-Internet art when I see art made for its own installation shots, or installation shots presented as art. Post-Internet art is about creating objects that look good online: photographed under bright lights in the gallery’s purifying white cube (a double for the white field of the browser window that supports the documentation), filtered for high contrast and colors that pop.”

Artists started dissociating themselves from the label—Droitcour himself opens his article saying “Most people I know think ‘Post-Internet’ is embarrassing to say out loud.” Other critics, curators and art professionals joined him in proudly declaring their hate or intolerance against Post internet; and when, in 2016, New York based collective DIS—working on the edge between curating, art making and fashion—curated the Berlin Biennale, the event—called The Present in Drag – was both perceived as the ultimate celebration of post internet, and its swan song.

The story of Post internet is interesting because it shows the evolution of an art movement in the present shock. After the first years of community and research (the years of surfing clubs, circa 2006–2012), Post internet met the expectations and the demands of an art world that wanted more art reacting to the digital shift; this made it vulnerable to the market dynamics of the art world, which caused an inflated attention and an oversimplification of its aesthetic and cultural instances, that turned it into a trend. In a bunch of years (2013–2016) people got tired of it, and the celebrated trend became the subject of hate and refusal.

The speed of this process is, of course, related to the speed at which information travels today, and to its abundance. If, in the past, it took years or even decades to a style to become a global language—through traveling exhibitions and catalogues, articles on printed magazines, oral reports of the few real globetrotters etc.—today information and things travel faster, and in order to know what’s happening right now in New York, Berlin or Beijing, one just needs to turn her favorite social network on. As an art practice that relied consistently on online circulation and mediated experience, Post internet became widely visible very fast; but—turned into a fashion—it oversaturated our gaze even faster.

The shift, in its perception, from something new to a fashionable trend requires some consideration, too. As Yves Michaud explained: “When novelty becomes tradition and routine, its utopian sides disappear, and what is left is just the process of renewal […] When permanent renewal takes command, fashion becomes the only way to beat time.” Fisher’s words about the “precorporation” of what’s new and alternative also come to mind: when novelty is accepted by the system it immediately turns into the “new normal.” This process may seem alien to an art world that since postmodernism namely doesn’t believe in a linear, progressive evolution of art anymore, but it isn’t. As Boris Groys explains in his essay “On the New,” contemporary art is the result of a dialectic between the museum, that recognizes art as such, and artistic practice: which needs to prove to be new, lively and different from what’s already collected to be recognized as art, but turns into the new tradition at the very moment in which this recognition happens, and it enters the museum. This way, the dialectic between the museum and the new turns into an infinite loop, and paradoxically, the museum becomes the space that produces “today” as such, “the only place for possible innovation.”

The problem is: if innovation is immediately incorporated, emptied and turned into fashion, what’s for? What chance has an original, new development to evolve slowly, to reach maturity, and to last in time? It’s hard to say. Looking at Post internet from the point of view of this moment in time, one thing that we may notice is that the “Post internet” label may have become unfashionable and outdated, and what was recognizable and trendy in its visual aesthetics and addressed topics may have been dropped out; but many artists that started their career under this tagline seem to be here to stay; and more importantly, Post internet seems to have completely changed the relationship between mainstream contemporary art and digital media and culture. Its topics and languages are now perceived as relevant to understand the time we are living in, and some of the artists that are dealing with them are recognized among the major artists of our time. How all this might be vulnerable to the present shock, it’s what we will discuss in the final chapters of this text.

Precorporation

(or Kanye West Fucked Up My Show)

On May 7, 2009, US born, London based artist Paul B. Davis opened his second solo show at Seventeen Gallery, London. The exhibition’s title was Define Your Terms (or Kanye West Fucked Up My Show). According to the press release, the show “[…] was instigated by a semi-voluntary rejection of a practice that, until very recently, was central to his creative output and figured prominently in his debut exhibition at the gallery—‘Intentional Computing’ (2007). A curious turn of events led to this unforeseen repudiation and redefinition of practice: “I woke up one morning in March to a flood of emails telling me to look at some video on YouTube. Seconds later I saw Kanye West strutting around in a field of digital glitches that looked exactly like my work. It fucked my show up… the very language I was using to critique pop content from the outside was now itself a mainstream cultural reference.

Paul B. Davis, The Symbol Grounding Problem, 2009. Single-channel video with sound, production still, courtesy the artist

Contentiously dubbed ‘datamoshing’, (or ‘compression aesthetics’, as Davis prefers to describe it), this practice ultimately emerged out of artefacts inherent in the compression algorithms of digitally distributed media. Davis seized upon the glitchy pixelation that is often present while viewing YouTube clips or Digital TV, and repurposed it as a tool of cultural rupture. Alongside other artists such as Paper Rad, Sven König and Takeshi Murata, he engaged this effect as a tool for aestheticized intervention, a fresh framework for analysis, and a new visual language.”

As the press release also suggests, “In contemporary culture, mainstream media pilfering of independent artistic production is expected.” It even evolved into a new profession, cool hunting: people with a sensibility for novelty, who often took the same classes of the people developing it in underground circles and in the niche world of contemporary art, are sent out by mainstream firms to capture innovation and turn it into a new trend. Yet if, in the past, innovative aesthetics and cultural proposals could count on an incubation time before being swallowed, digested and repurposed by mainstream culture, in the age of instant global communication this timeframe has squeezed down to almost zero. It took 50 years to Andy Warhol’s colorful, solarized serigraphs to be turned into a Photobooth digital effect; it took two years to Paul B. Davis’ compression aesthetics to become mainstream, thanks to Kanye West’s Welcome To Heartbreak video clip.

&

You might be aware of it—but when it happens to your work, depriving you of the possibility to develop it further, and to see where it’s bringing your visual research, it’s experienced as a shock—actually, a form of present shock.

For Davis, this shock produced the awareness that he was walking on the wrong way, and “[…] served as a trigger to directly engage his growing concern that current artistic methods for grappling with digital culture—hacks, remixes, and ‘mash-ups’ among them—are ill-equipped for sustaining serious and self-reflexive critical examination. As Davis has commented, ‘These methods generate riffs… restatements or celebrations of existing cultural behaviours, and artists who use them are seemingly unable to either offer incisive alternatives or generate new cultural forms. I was one of these artists, making these riffs, and I’d come to realize their limitations.’”

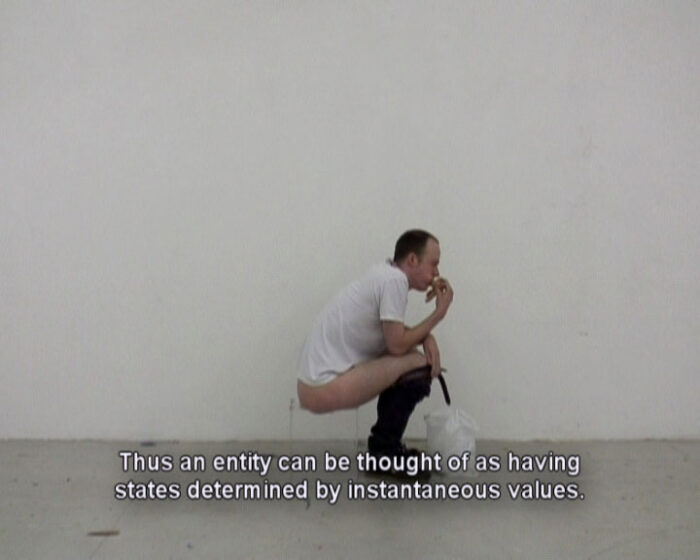

The works he developed in two months for his upcoming exhibition came out from this awareness. One of them, The Symbol Grounding Problem, is a single channel video in which Davis, sitting on a perspex box, eats a bacon sandwich and defecates at the same time while, in a voice-over, philosopher Luciano Floridi speculates about Philosophy Of Information (POI), according to which “as our digital technologies become completely integrated with human Being and we begin to live inside models of ourselves which are more ‘intelligent’ than we are, information that creates this environment becomes the defining characteristic of Existence.” I still can’t find a better illustration of the present shock: a man sitting in an empty room, eating and pooping at the same time.

Paul B. Davis was not the only victim of this accelerated incorporation that Mark Fisher calls ‘precorporation’, although he was one of the few to be straightforward and coherent in his response. In November 2012, the internet reacted in an outcry against hip-hop singers Rihanna and Azealia Banks. A funny article posted on November 12 on Buzzfeed was titled: Web Artists Are Furious At Rihanna And Azealia Banks. What happened was that, in that weekend’s Saturday Night Live, Rihanna performed her hit Diamonds in front of a green screen, where visuals featuring “screen saver–like graphics, garish 3-D animations, and deep-sea imagery” were projected. Apparently in response to this performance, on Sunday morning Azealia Banks’s videoclip for her new song Atlantis showed up online.

Both Rihanna’s performance and Banks’ videoclip shamelessly appropriated the visual aesthetics of an underground visual trend that developed mainly on Tumblr along the previous months, and that was christened “seapunk” only in 2011. Seapunk featured color gradients, 3D models of objects and architectures, aquatic-themed iconography such as waves, mermaids, palm trees and dolphins, animated gifs and nostalgic allusions to the visual culture of the Nineties. From the Tumblr dashboard, it quickly penetrated into electronic music, do-it-yourself fashion and hairstyling, but Rihanna and Banks (and later on, Beyoncé) brought it at the top of mainstream pop music.

To react against this shame, Chicago based artist Nick Briz made Diamonds (Green Screen Version), re-appropriating Rihanna’s TV show while simultaneously re-enacting the strategies of versioning and remixing performed by Austrian artist Oliver Laric’s in Touch My Body (Green Screen Version): a work made in 2008, where Laric green-screened Mariah Carey’s video clip with the same name, deleting everything but the singer’s body, and released the video online inviting web users and other artists to contribute with their own version. Briz did the same with Rihanna, and about fifty artists – either involved or not in the seapunk movement – took part in the game.

If Paul B. Davis’ reaction to his visual research’s incorporation into mainstream culture rejected appropriation as an effective cultural strategy, reinventing his own language (by actually reverting to a more severe and visually brutalist conceptual approach), Briz seems to invite us to consider the relationship between experimental research and mainstream culture as an infinite loop with no exit door.

Media Art and Obsolescence

Obsolescence is notoriously a problem in media art. If it’s true that all contemporary art that doesn’t rely on traditional media such as oil painting or marble sculpture raises new, specific issues when it comes to its preservation, these issues increase exponentially in terms of number and complexity when you are confronted with digital and electronic media. Artistic media may be durable or ephemeral, but when it comes to electronic media, obsolescence is not an accident: it’s a built-in feature, as the expression “planned obsolescence” reveals. How old is your smartphone? Mine is two years old, and will need to be replaced soon. The battery runs out in five hours or less, and it’s designed to not be removed or replaced. The screen is broken. When I bought it, I was happy of its 16 gigabytes of memory; yet, half of them is taken by apps (most of them, system apps that I don’t use but can’t remove) and one third by firmware, so that every two months I have to remove my pictures and videos if I want to keep using it. Maybe, if I were more careful, it would have survived another two or three years, but only to get frozen when I was using that recent app requiring too much RAM, or to tell me awkwardly that I can’t install the latest version of my favorite browser because it’s not supported by my system. This is planned obsolescence, and it’s designed to bring you to the store to buy the next model of your old device.

Hardwares break up or get old; softwares get updated. As commercial products tied to the laws of the market, they both run the risk to get out of production. If you make art with them, or incorporate them in your art, you know that, sooner or later, you will have to deal with restoration, replacements, or emulation. This is all well known to artists, collectors and conservators, and it’s the reason why media art preservation has become an important field of research in recent years.

Yet, media art preservation rarely takes into account another form of obsolescence, which is more subtle but way more dangerous and difficult to deal with: let’s call it the loss of the context. Simply put, the context is the cultural, historical, social, political, economic, technological background in which a specific work of art appears and makes sense to its own audience. When you belong to this context, understanding the artwork is relatively easy and immediate; when you don’t, explanations and storytelling may help to some point. You need to know something about New York and the Eighties if you want to understand Basquiat; post-cubism, Paris and the Twenties, if you want to approach Tamara de Lempicka. Filtered through history, art may lose its immediacy; but, in the best cases, it also demonstrates its ability to speak beyond time—to exist beyond time.

In the age of acceleration and the present shock, context changes very fast, sometimes abruptly. This is especially true in digital culture, where products, topics, ideas and trends that might be commonplace on a global scale at some point in time, may require an explanatory footnote or a Wikipedia reference two or three years later. This is, for art, a completely new form of aging. The art form in which it manifests in the most radical way is net-based art. Here, the context is not only the world around us and the information we can gather, retrospectively, about it in a certain moment in time; it’s also the very socio-technical infrastructure in which the art is experienced, the internet (within the browser within the desktop interface). This infrastructure evolves endlessly, yet seamlessly, on both the technological and social level; but since it’s persistent, and we keep describing it using more or less the same words, the scale of change is always quite difficult to grasp. Take the internet population as an example. In 1995, 32 million people were online; in 2005, one billion; in 2015, 3 billions; it grew from a small state into a continent, and from a population of academics and students from developed countries into a global population of users, most of them from developing countries. Or take the browser: in 1995, the most popular browser was Netscape, that doesn’t exist anymore; it had no tabs, it had a simple, modernist design and presented mostly static pages with text and small animated gifs. In the late Nineties, the browser wars were won by Internet Explorer, that doesn’t exist anymore either. Today, Google Chrome, Safari and Firefox are the most popular browsers and are implemented on many different networked devices.

I am a teacher. Every year, I go with my students through the history of net based art, showing examples of artworks from the last 25 years. Most works require, of course, a lot of contextual information in order to be enjoyed and understood. As years pass by and generations change, some works may require some more contextualization, because things that were commonplace a few years ago have disappeared or been forgotten. Friendster and Myspace were popular social networks in the first decade of the Twenty-first century; but if you have to introduce a work such as Myspace Intro Video Playlist (2006) by Guthrie Lonergan to somebody who started inhabiting the internet around 2010, you need to introduce them; you need to explain how different they were from the current social networking experience; you need to explain why, in 2006, an artist was more interested in arranging collections and playlists of social media rubbish than to create something original himself. After that, they may be able to go on by themselves, enjoy the work as a contribution to the ongoing tradition of portraiture, as an anticipation of selfie culture, or as an anthropological research on early social networking.

The most frustrating experience happens when you realize that this effort of offering contextual information is useless or even damaging the work. This usually happens when the work itself established a relationship with the viewer based on immediate recognition and surprise; when, in other words, its strength relies on a dynamic relationship with its context that has gone lost. The effect is similar to what happens when you try to explain a joke: people may finally understand it, but they won’t smile; as in a joke, the emotion should be the consequence of instant understanding; if this doesn’t take place, no explanation can help. This paradoxically happens when the context apparently survived, but changed beyond recognition. Take YouTube, for example.

In 2007, YouTube was a newborn platform allowing people to share videos and build their own channel. It mainly hosted amateur videos and pirated mainstream content. Its motto was “Broadcast Yourself,” and the first video it hosted was a low res, blurry video called “Me at the zoo.” Its community was made of people, mostly young, competing for attention in a place free of advertisement and commercial dynamics. In 2007, American artist Petra Cortright uploaded her first video, VVEBCAM, and started shaping her online persona. She played with the character of the webcam girl, subtly subverting it from the inside. Sometimes she danced, sometimes she said something, most often she just looked at the camera, silent and with blank expressions, while playing with video effects and animated GIFs. She didn’t change the titles of the videos, often keeping the name and extension of the file, looking dumb and amateurish. She tagged these videos using improper tags, related to sex, porn or pop culture, thus distributing them to people that were looking for something else, and mostly not interested in art. In the viewer, this YouTube intervention used to produce an instant reaction, a disturbing mix of pleasure and discomfort, of recognition (it fits to the platform and its trends) and alterity.

They are still there, but meanwhile YouTube has become a completely different place. It turned into a controlled platform, where copyright is protected and violations of its terms of service are punished. Uploaded in 2007, VVEBCAM was removed by YouTube in 2010 because of the misleading use of tags, forcing the artist to change the descriptions of other videos to prevent their removal from the platform they inhabited. Mainstream media have their own YouTube channel. Advertisement is everywhere. Amateur content is still uploaded, but without promotion and likes it’s kept under the level of visibility. The webcam girl has been replaced by ASMR video girls and influencers, who make highly professional videos and mostly want to monetize the attention they manage to get.

The original context in which these videos were uploaded, the culture and habits they responded to, are lost for those who weren’t there at the time; and are difficult to recover even for those who were there, as the current context is influencing our perception and memory. They can be reconstructed of course, with words and stories or through documentation and emulation; but the feeling is still that they belong to another age. Even if not a single bit has changed in the actual work, they look old, much older than any other artwork produced in 2007. A feeling of nostalgia and a taste for retro may affect their perception and understanding.

This happens all the time, online. Media art preservation cares for works that suffer from link rot, incompatibility with current browsers, use of plugins and softwares which are not supported anymore. Yet, little can be done for artworks that are still in working conditions, but are floating like ancient relics on a web that changed around them beyond recognition, on all levels: technical (infrastructure, bandwidth, screen sizes, interface design, softwares, devices and modes of access), social, economic, political. Try to access an early work of net art on a mobile phone, while walking the dog, and you will get this immediately.

We can’t but recognize the precarious relation of the works more embedded in digital culture with time, and accept it as their “ontological condition,” as Gene McHugh suggests in a short note written for the second edition of the book Post Internet in 2019: “What feels most relevant in these pages, ten or so years since they were written, is anything having to do with the effect of time. Post-internet art and writing about post-internet art is at its best when it evinces a self-consciousness about the precarious relationship of digital culture and time. What was so vital then, often appears dated now. That fact, it’s becoming more and more clear, is the ontological condition of post-internet art. Most of it is an art of the right now and quickly becomes dead, at best a historical example. That sounds disparaging, but I don’t exactly mean it that way. At the time it mattered more than anything.”

Trends and Hype Cycles

Technological trends may have a consistent impact on this precarious relation with time. To put it simply: art using digital media and responding to digital culture exists in a symbiosis with a living being—technology—whose evolution is affected by new technological possibilities, economic interests, political regulations. This sets an unprecedented condition for art, as its development—which traditionally (at least from the Eighteen Century) has been perceived as autonomous, and responding to its own raison d’étre and internal requirements—is in this case, at least in part, subject to the (often hidden) influence or control of an external process: technological evolution. Its forms, languages, aesthetics and topics are not the result of a free choice, but the consequence of what’s perceived as crucial, up to date, or fashionable today. Is art still art, when its agenda is other-directed and controlled by interests that are not artistic in the first place? How can an art that confronts itself with a present that is fluent and mutable, last in time and communicate beyond time?

Of course, in media art as in art in general, artists can always decide to stay on the side of the main current debate, to follow the path of an inflexible line of research without engaging in the conversation. This has always happened, and will always happen. But most contemporary art wants to engage with the present, with the here and now, and in a post digital age this means to engage with topics and technologies that may be subject to a hype cycle.

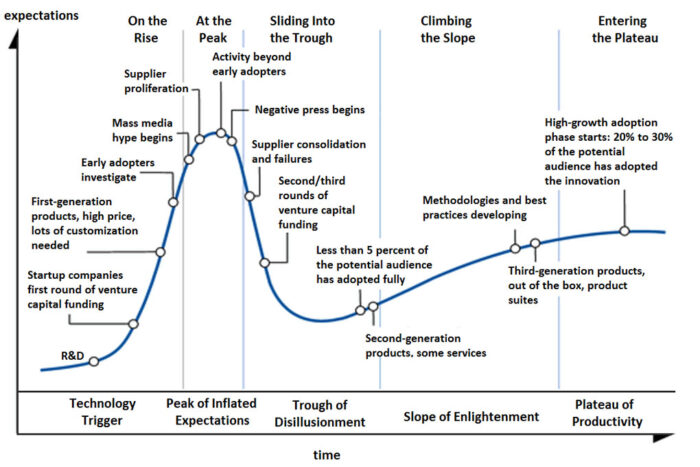

The Gartner Hype Cycle. Image CC NeedCokeNow, courtesy Wikipedia

The hype cycle is a branded graphical presentation and a descriptive model developed and used by the American research, advisory and information technology firm Gartner to represent the maturity, adoption, and social application of specific technologies. According to this model, a cycle begins with a “technology trigger:” a new, potentially game-changing technology is presented and gathers publicity and media attention, often before a usable product even exists. The technology collects a number of success stories and rapidly reaches the “Peak of Inflated Expectations.” Soon afterwards, “Interest wanes as experiments and implementations fail to deliver. Producers of the technology shake out or fail. Investment continues only if the surviving providers improve their products to the satisfaction of early adopters:” the technology has entered the “Trough of Disillusionment.” Specific products and companies may fall victims of this phase, and never come back. But the technology itself may survive, and either enter another hype cycle in a few years, or proceed along a slower, cautious development in the “Slope of Enlightenment.” If this happens, at some point the technology will reach the so-called “Plateau of Productivity,” the moment in which mainstream adoption starts to take off.

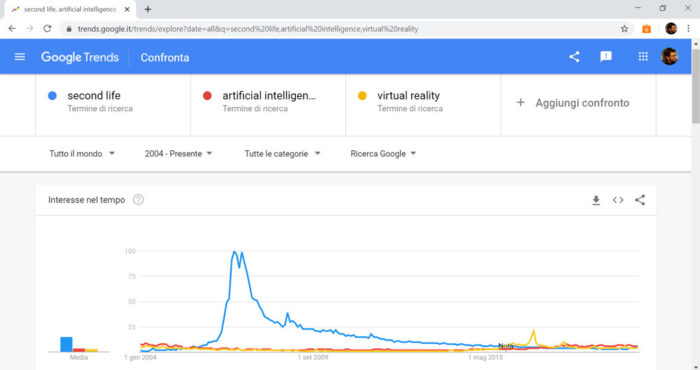

This model can be used to read the development of many technologies, on a macroscopic or microscopic level. The World Wide Web took off in the mid Nineties, grew exponentially until the end of the century, and then collapsed under the burst of the dotcom bubble; many web based companies and online markets died; those which survived, such as Amazon, or where designed during the crisis according to a different economic model, such as Google, grew up slowly and reached the Plateau of Productivity, and now literally dominate the internet and its development. Social networking started with companies such as Friendster and Myspace, but it was brought to the Plateau of Productivity by Twitter and Facebook. Graphical chat softwares were hyped technologies in the late Nineties, with systems such as The Palace, and ten years later, with Second Life; The Palace disappeared and Second Life never really came out from the Trough of Disillusionment, but today millions of people are interacting day and night in online virtual worlds such as The Sims, World of Warcraft or Minecraft. However, as hypes may be recursive, it’s always difficult to tell if the current success of a given technology should be interpreted as a new hype or as the proof that it reached the Plateau of Productivity. To put it differently, it’s hard to define mainstream adoption: millions of users and the engagement of many different industries may look like a success, but in technology, the true mainstream is reached when your grandma is using it, too.

If the hype cycle model can be only applied in specific cases, we must recognize that all the recent history of media art has been conditioned and somehow determined by trends and developments in technology. In the late Eighties and early Nineties, interaction and virtual reality were the keywords in the technology world; most media artworks played with user interaction and forms of immersion, and terms like Interactive Art and Virtual Art were highly debated. The introduction of CD Roms in the early Nineties challenged artists to develop hypermedia projects, and Multimedia Art became a trending definition; then, the World Wide Web showed up, and Internet Art became the umbrella term for almost anything.

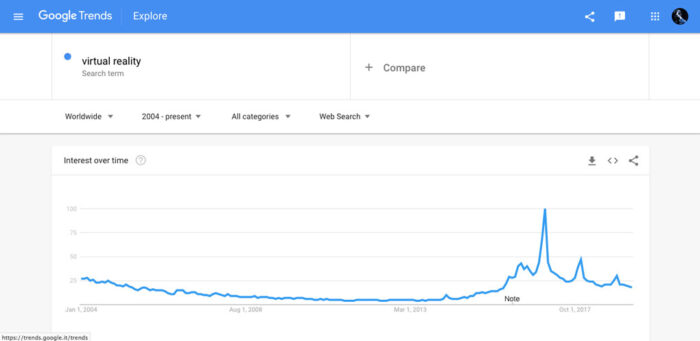

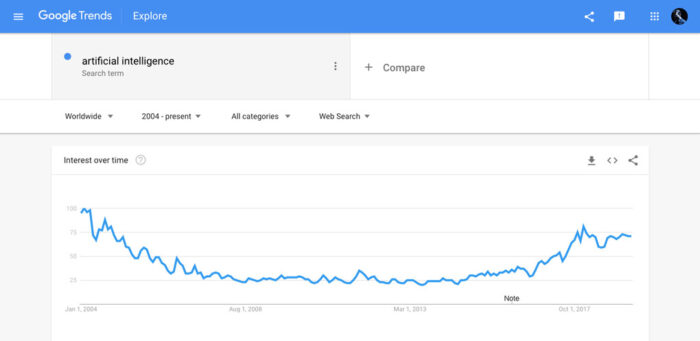

Until the late Nineties, software could only be developed by commercial companies; but growing access to powerful desktop computers and programming skills, together with the success of the Free Software/Open Source movements, gave artists the possibility to develop and distribute software independently, often with a critical attitude: Software Art was born. Game Art became popular in the early 2000s thanks to the explosion of videogames as a mass culture and mass industry, and to the release of open game engines that could be used to modify commercial games or develop entirely new games. In the mid 2000s art started to engage with social media and online virtual worlds, which caused a return of popularity of terms such as virtual reality and virtual art. Then, at the beginning of this decade, big data became a trending topic, and technologies such as Augmented Reality and 3D printing started to be commercially viable and widely used. Today, Artificial Intelligence is the new black, and Virtual Reality—often combined with Augmented Reality in applications of so-called Mixed Reality—is experiencing a new backdraught.

This short account may be oversimplified, but it shows how media art production, as well as the key terms and labels used to discuss it may be affected by the main trends and the ups and downs in technological development. And if, on the one hand, this dependance has caused—and sometimes still causes—frequent accusations of being a demo of the technology used, rather than an autonomous art form, on the other hand it raises concerns about this art’s reception and understanding in the present time, as well as in the near and remote future.

Virtual Reality